Archaeologia Volume 29 Section XV

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section XV is in Archaeologia Volume 29.

Effigy of King Richard, Ceur de Lion, in the Cathedral at Rouen. Communicated to the Society by Albert Way, Esq., M.A., F.S.A. in a Letter addressed to John Gage Rokewode, Esq., F.R.S., Director.

[Note. Two plates are missing from the text so I've added three photos of my own of the effigies at Fontevraud Abbey.]

Read 25th March 1841

Dear Sir, March 22, 1641.

THE announcement in the French journals of the month of August 1838, that by the researches of the distinguished antiquary of Normandy, M. Deville, the lost effigy of King Richard had been brought to light from beneath the pavement of the choir in Rouen Cathedral, induced me to take the earliest opportunity of visiting that city, with the special purpose of examining so interesting a memorial. During the last summer I had the occasion of correcting the observations previously made, and which I had reserved in the hope that no long interval would elapse, before a second similar investigation, conducted with the same enthusiasm, and rewarded by a like success, might enable me to add to this notice of the relics of the Lion-hearted Richard, some account of the Tomb of Henry his elder brother, whose remains were deposited near to the spot where the effigy of Richard has been discovered, and whose memorial shared the same fate, by which both tombs were barbarously condemned to be destroyed. Owing to unexpected circumstances no further researches have hitherto been permitted, and as I am not aware, that during the interval any accurate report of the discovery made in 1838, has been made public, I am induced to hope that a short notice on a subject so interesting both in relation to early art, and to monumental antiquities, may not be unacceptable to the Society.

There are many circumstances of interest connected with M. Deville's discovery, and communicated to me by him with the most friendly and obliging liberality, into which it is not my purpose to enter in detail, because he has signified an intention of giving a minute account from the notices drawn up by himself at the time, as a supplement to his valuable work on the monumental remains in Rouen Cathedral; this promised communication is, as I believe, withheld only in the expectation that further researches, which he still hopes to be permitted to undertake, may lead to the discovery of the other lost memorial to which I have alluded, namely, the effigy of Henry, the eldest son of Henry IInd. crowned King in his father's life-time, and interred in the choir of Rouen Cathedral in 1183.

Richard having received his death wound under the walls of the castle of Chaluz in Limosin, directed that his body should be interred at Fontevrault [Map], at the foot of his father's tomb; his effigy is still preserved there, and has been accurately represented by Charles Stothard. His heart he bequeathed to the Canons of Rouen, to whom in his lifetime he had been a benefactor, and who gratefully enshrined the relic in a sumptuous receptacle, as we learn from a contemporary writer, Guillaume le Breton.

"Cujus cor Rotomagensis [Whose heart is Rouen]

Ecclesie clerus argento clausit et auro, [The clergy closed the church with silver and gold]

Sanctorumque inter sacra corpora, in æde sacratâ [And among the sacred bodies of the saints, in the sacred meal]

Compositum, nimio devotus honorat honore; [The compound, the most devout, honors with honor]

Ut tante ecclesia devotio tanta patenter [So much devotion to the church so openly]

Innuat in vita quantum dilexerit illum." [He hints in life how much he loves him] Putipripos, Lib. v.

Of what precise description was the memorial here alluded to as originally erected by the Church of Rouen, a question arises which demands a detailed inquiry: with respect to the identity of the effigy discovered, it may be unquestionably asserted, that it is the same, which was preserved until 1734 on the south side of the choir at Rouen, the acknowledged memorial of King Richard, and as such engraved by Montfaucon, in the second volume of his Monarchie Francoise, plate xv, from a sketch made at the beginning of the last century by the direction of M. de Gaigni¢res, and now preserved in the collection which bears his name, in the Cabinet of Engravings at the King's Library in Paris. The representation is however deficient in accuracy, and the attitude of the figure changed: the only memorial known to exist of the entire tomb with the effigy, is preserved in the valuable collection of drawings of monuments in France, bequeathed to the Bodleian by Gough, and formed of the original sketches taken by the artist who accompanied M. de Gaigniéres in his archzological tours, and furnished Montfaucon with the greater portion of his illustrative materials. From this sketch, of which I inclose you a copy for the inspection of the Society, (Plate XIX.) it appears that the effigy was placed on a plain slab, which rested on the backs of four couching lions: several tombs of the same design occur on the continent, to which the date may be assigned of the earlier years of the 13th century, and the memorial of Henry at Rouen, to which I have alluded, was, as appears by a drawing in the Bodleian, almost precisely similar. It was only in 1734 that these interesting sepulchres disappeared. The Canons of Rouen thought fit to add to the embellishment of the sanctuary, by elevating it considerably above the level of the surrounding area, and at this period the tombs of Henry and of Richard, of the Regent John Duke of Bedford, and Charles V. King of France, whose heart had been there deposited in 1380, were totally demolished, no memorial being preserved, except a small inscribed slab of marble inserted in the new pavement, to mark the position of each tomb, that had been thus condemned as encumbering the area of the choir. A lozenge-fashioned slab on the south side bears still the following inscription:

COR RICHARDI REGIS ANGLIE NORMANNIE DUCIS COR-LEONIS DICTI OBIIT ANNO MCXCIX.

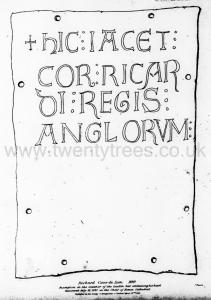

Having given this general account of the original character of the tomb, as far as existing authorities assist us, and of its destruction, I must allude briefly to the circumstances that led to, and that attended the discovery, which is the subject of the present communication. It occurred to my friend, M. Deville, that, although in the destruction of the tombs themselves no portion had been preserved, yet possibly the heart, or the mouldering bones, that lay beneath, might have met with some respect, and the inscription on the pavement seemed to afford some indication that these remains, and possibly some fragments of the tomb or the effigy might there be discovered, near to the spot where such a relic as the Lion Heart had been originally enshrined by the pious Canons of Rouen. Enthusiastically impressed with this idea, he commenced, with the sanction of the authorities, an excavation near the spot alluded to, on July 30, 1838, adjoining the entrance to the choir from the south aisle, opposite to the vestry. On removing the pavement a compact bed of mortar was perceived, which had by time acquired such a degree of hardness, that it was with difficulty broken up: about two feet below the surface, was discovered imbedded in this mortar, the effigy of Richard, all the cavities of the drapery and other parts of the figure were filled up with the cement poured over it, apparently to form a compact substratum for the new pavement of the choir: the projecting parts of the head, the hands and feet had apparently been levelled by the hammer with the same intention. When cleared, however, from the mortar, which had become almost as hard as the stone itself, the defaced, but still highly interesting memorial proved to be in a more perfect state of preservation, than might have been anticipated, and the painting and gilding with which every part had been decorated was on many portions still perceptible. The effigy having been carefully removed into the chapel of the Blessed Virgin, where it still remains, a long and fruitless research commenced beneath the spot where it had lain, with the hope of discovering the heart of Richard; and after excavating till the undisturbed soil was attained, and all expectation of success began to fail, the interesting relic was at length found concealed in a closed cavity which had been formed on purpose in the adjoining lateral wall, built at the time the sanctuary had been raised, between the piers by which it is surrounded, and enclosing the newly elevated area. On July 31st was this remarkable relic brought to light: the heart was found enclosed within two boxes of lead, the external one measuring 17 inches, by 11, and about six inches in height; within this was a second interior case, lined with a thin leaf of silver, that time had in great part decayed, and thus inscribed within, in rudely graven characters,

+ HIC: IACET: COR: RICAR DI: REGIS: ANGLORVM.

That this inscription, so deeply fraught with tie magic charm that such memorials of times long past possess, is truly contemporary with the decease of Richard, no doubt can be entertained: the fac-simile accompanying this notice (Plate XX.) will supply sufficient evidence to any one who is the least versed in French paleography. It is, however, satisfactory to compare its character with that of the inscription on the chasse presented to the Cathedral of Rouen towards the close of the 13th century, by Drogo de Trubleville, which bears the name of King Richard, and presents the most perfect identity in the form of the charactera.

Note a. It is now preserved in the Musée 4' Antiquités at Rouen, and bas been represented in the Memoirs of the Antiquaries of Normandy, 1836.

It may here be not unworthy of observation, that the epithet "Coeur de Lion" does not appear to have been assigned to Richard, until after his decease, and we find it not in this interesting inscription. It were indeed satisfactory, if we could regard the newly discovered effigy of the King as a work of contemporary execution, with the same confidence that enables us to pronounce an opinion upon the inscription. Differing materially from the effigy at Fontevrault, which may reasonably be considered as a work coeval with the decease of the Monarch, the effigy at Rouen at first sight in its less exaggerated proportion, greater freedom of design, and more skilful execution, impresses us with the conviction that it was sculptured considerably later than the period of Richard's untimely end. The careful examination, however, of monumental sculpture as displayed in existing specimens in northern France, the comparison of this work with the effigy of King John in Worcester Cathedral, and with the character 'of design exhibited on the great seal of John, have led me to a conviction that Richard's effigy at Rouen was sculptured not long subsequently to his decease. It measured, previously to the mutilation of the ornaments of the crown, nearly seven feet, the entire block of stone from which it is sculptured measuring 7 feet 8 inches.

The features have materially suffered; the nose and chin have been rudely levelled, apparently at the time when the tomb was demolished, and nearly all the original surface of the sculpture is worn away: yet, with all these injuries, the features retain still a degree of stern dignity of expression, and a character more marked than strikes the eye in viewing the effigy at Fontevrault, which, more interesting as being more closely contemporary with the decease of Richard, is yet inferior in many respects. It is remarkable, and at first view disappointing, that these duplicate effigies do not correspond; some degree of identity of features may indeed be traced, but the details of costume are wholly different; in design and in ornament the two statues are totally dissimilar, and it may safely be asserted that the Norman sculptor could never have seen the representation of Richard that existed in Poitou. Stothard's accurate etchings render any detailed comparison unnecessary. On the effigy at Rouen we perceive the hair carefully divided on the crown of the head, and arranged in small waving locks, which falling full on each side, and covering the ears, form at their extremities a regular curl all around the head: the hair on the face appears to have been wholly shaved, for neither beard, whiskers, nor mustachios appear, as in the representation at Fontevrault. The hair of the head appears to have been painted with a sandy red, or ochre colour. The upper ornaments of the crown consisted of four large leaves, alternating with four small knops or pomels, which seem to have been spirally grooved: the circle of the crown, which bears these ornaments, measures two and a half inches in depth, and is divided by pearled borders into eight pannels, slightly depressed, and each of which contained, as represented by brilliant colouring, a large gem, either emerald or sapphire, with two smaller gems, apparently rubies, on either side. All these gems are cut perfectly flat, and set in plain collets with their edges bevelled. The crown, although possessing some points of resemblance to the ornament that occurs on that of the effigy at Fontevrault, is not identical with any other crown that I have been able to discover; in conjunction with other details, it may possibly serve to fix precisely the age of the sculpture. The statue is not vested in the whole of the regal robes, as we see them at Fontevraultb; two garments only are perceptible, a long mantle of a blue colour, fastened by a tasselled band across the breast, the skirt raised, and thrown over the left arm, a fashion observable in other instances, and adopted probably to give greater apparent freedom to the design. Under the mantle is seen a single tunic, fastened at the throat by a square fibula, which serves to close a short slit in the front of the robe, according to a fashion seen in numerous effigies of the earlier part of the 13th century: this tunic is girt by a long girdle of blue tissue, harnessed with bars and quatrefoils of gold alternately, and furnished with a richly chased buckle and pendant. The colour of this tunic, which reaches to the ancles, was of a rich red, and it was probably, as well as the mantle, diapered in patterns intended to represent the rich samite or other elaborate tissues, of which the vestments of the great were formed at this period, such as we see displayed in Stothard's coloured plate of the Effigies at Fontevrault: the colour, however, is on this statue so defaced, that the details of the ornamental design cannot be ascertained. In the left hand was placed the sceptre, now totally destroyed, but it may be traced by a portion which remains in the hand, and by slight fractures on the surface of the stone on the ieft shoulder against which it rested. The fashion of the sceptre we learn from the drawing in the Bodleian to have been similar to that which occurs commonly in the 13th century; its head was formed of a large swelling bud of leaves, apparently just bursting open. The right hand appears to have held the band that attached the mantle, an attitude which is indeed ungraceful, but of rather frequent occurrence in contemporary sculpture. There are no jewelled gloves upon the hands, as at Fontevrault, the insignia of royal or hierarchical dignity: nor upon the feet do we find the buskins, but shoes of cloth of gold, or some richly embroidered stuff, cut out low on the foot in a fashion similar to that which is seen in the curious paintings on the south side of the Sanctuary at Westminster, and fastened by latchets which meet over the instep, and are buckled or buttoned together. (Plate XXI.)

Note b. We learn from the Annales Ecclesia Wintoniensis an interesting fact in relation to the interment at Fontevrault: "Scitu quidem dignum est, quod dictus Rex sepultus est cum eadem corona et ceteris insignibus Regalibus, quibus precedente quinto anno coronatus et infulatus fuerat apud Wintoniam." [It is indeed worth knowing, that the said King was buried with the same crown and to the rest of the distinguished royals, in which he had been crowned in the fifth year before and inspired at Winton] Anglia Sacra, tom. i. 304.

The head of the effigy rests upon a square cushion, the case or pillow-bere in which it is inclosed was of a bright red colour, diapered with a pattern of gold, and had small flat knops at the corners; it opened only at one end, as may be seen at the right side of the head, and was closed by a double lace that passed through eyelet holes in the embroidered edges of the pillow-bere. The feet rest against a lion, couching upon a mass of rock, or rather, as it would appear, an assemblage of rounded or water-worn pebbles: and in this part of the tomb some singular details present themselves, which must not be over-looked. In a cavity of this rocky bank, is seen the head of a hare or rabbit just peeping out of its burrow; a little above is a dog warily watching the mouth of the hole, and lying in wait for its prey: at one side is represented a large lizard crawling among the rocks, and at the other a bird resembling a partridge or a quail. I have met among the accessory ornaments of monumental sculpture with nothing analogous to this, and though convinced that what in itself may appear merely a trifling detail, was not placed here without design, I am quite at a loss to conjecture what could have been its import. It has been suggested to me by some antiquaries on the continent, that this sculpture may be allusive to the rights of the chase, the exclusive privilege of the King and the nobility, and which were preserved by Richard with the like jealous care, as by other contemporary princes, but this explanation appears wholly unsatisfactory.

The minuteness of detail with which I have entered into the description of the present state of this interesting effigy, may, I fear, seem tedious and unnecessary; I have thought it desirable, because I believe it possible that the statue may undergo some restoration, which, indeed, in part is perhaps indispensable, and moreover the decay of time, or wanton injury, may hereafter efface those indications of its original appearance, that now are sufficiently discernible. There is something so striking in the character of this piece of sculpture, disfigured as it is by reckless mutilation, it is so superior to the effigies at Fontevrault, to that of King John at Worcester, and generally to the existing memorials of the earlier portion of the 13th century, that a few observations, which may perhaps lead to determine the precise period at which the sculpture was executed, will not I hope be without interest.

Richard had with his dying breath directed that his body should be transported to Fontevrault, and there deposited, in token of penitence for his past conduct and want of filial affection, at the feet of his father Henry the Second: his brain, his blood, and viscera, he bequeathed to the Poitevins, being, as some chroniclers have represented it, the less worthy portion of his remains, in remembrance of their treacherous conduct towards him in times past; and these relics appear to have been interred at Charroux, the first town in Poitou that lay in the course which the funeral convoy would probably take, in proceeding towards Fontevrault from the Limosin, It would be interesting to ascertain whether any memorial of this singular deposit was, as seems highly probable, in accordance with contemporary usage, erected at Charroux, or any tradition of the circumstance has been preserved at that place, but hitherto all researches on the subject have been fruitless.° Last of all, in testimony of his special regard, Richard bequeathed to the Canons of Rouen, his heart, according to the Chronicle of Normandy, "en remembrance d'amour."

"His herte inuyncible to Roan he sent full mete, For their great truth, and stedfast great constaunce." Harpyno, Metrical Chronicle.

Note c. At the end of the "Itinerarium Regis Richardi in terram sanctam," written by Geoffrey Vinisauf, who appears to have accompanied him in his expedition, are some Latin verses, which in Gale's edition are attributed to the author of the chronicle. (Hist. Angl. Script. vol. ii, 433.) In a MS, of this Itinerary, preserved in the British Museum, a distich, which occurs among the verses printed by Gale, is thus given,

"Epitaphium ejasdem (Regis Ricardi) ubi viscera ejus requiescunt. Viscera Kareolum, corpus Fons servat Ebraldi, Set cor Rothomagus, magne Ricarde, tuum." Cott. MS. Faust. A. vit.

This inseription is, with some variations, given by Brompton, Decem Scriptores, col and Otterbourne, Chron. Regum Angl. vol. i. 73, ed. Hearne.

Gervase of Dover, a contemporary historian, describing the obsequies of Richard, relates, "cor ipsius grossitudine prestans, Rothomagum delatum est, et honorifice tumulatumd [lending his heart to his coarseness, he was brought to Rouen, and honorably buried]. With what intense interest must those, who after the lapse of six centuries, were permitted to gaze on the precious relic, have viewed the heart, once as remarkable for its physical capacity, as by its moral developement, withered, as it was described to me, to the semblance of a faded leaf. Richard died on the 6th of April, 1199, and in all probability the token of his undiminished affection was conveyed forthwith to its final resting-place at Rouen: yet had it been immediately placed in the choir of the Cathedral, it scarcely could have escaped the rapid conflagration which occurred on April 10th, 1200, when the Cathedral with all its rich contents, books, ornaments, and bells, became a prey to the flames, Perhaps was it owing to the delay necessary in order to fabricate the costly decorations with which the gratitude of the Canons enriched the memorial of their benefactor, that the heart of Richard did not perish in the general ruin of the church: and not many years eiapsing before by the zeal and energy of Archbishop Gautier, who presided over the see until his death in 1207, the fabric had again risen from the ashes, we find direct mention of the sumptuous memorial enriched with gold and silver, as Le Breton describes it, wherein the lion heart had been enshrined. A contemporary historian, Albericus Trium Fontium, whose chronicle closes 1241, speaks of the noble sepulchre of Richarde, which in the Croniques de Normandie is said to have been ** sepulture Royal d'argent," or "une Chasse d'Argent:" and to this chasse I imagine that Le Breton refers in the lines,

"cujus cor Rotomagensis Ecclesiz clerus argento clausit et auro," [the heart of which the clergy of the Church of Rouen closed with silver and gold]

as the words appear quite as applicable to one of the elaborate works wherein at this period sacred relics were enclosed or enshrined, such as the chasse of St. Romain, and that of St. Sever, which still exist at Rouen, as to a clausura, cloture, or railing of silver, whereby the memorial was originally, as some have supposed, surrounded. The precious portion of the memorial of Richard, of whatever nature it was, disappeared as early as 1250, when it was appropriated towards the ransom of Saint Louis, who had been captured by the Saracens at Damieta. The Chroniques de Normandie inform us that the "sepulture Royal d'argent," called in the edition by le Mesgissier the "chasse" that had contained the heart, "pour la rancon du rey Sainct Loys de France, quant il fut prisonnier aux Sarrazins, fut despecce et venduef."

Note d. Decem Scriptores, col. 1628.

Note e. "Cor suum misit Rotomagum, ubi nobilis ejus sepultura constructa est," [He sent his heart to Rouen, where his noble tomb was built] Bouquet, Historiens des Gaules, tom. xviii. p. 762

Note f. Roy. MS. 15 E. VI. f. 446 ve, and the numerous editions of the ' Croniques de Normandie,"' printed at Rouen, and Paris.

There arises here an inquiry of material importance in regard to the precise age of the effigy at Rouen, for in the printed Chronicles of Normandy, and in the History of the Province by Du Moulin, it is stated expressly, that when this "sepulture d'argent" was thus applied to make up the heavy sum demanded by the Soldan for the ransom of the French monarch, "au lieu mesme en fut faite une de pierre." This statement, which at first sight would appear conclusive, as to the age of the effigy, and to fix its date as of the middle of the 13th century, seems to me on various grounds questionable. The passage that thus asserts that a sepulchre of silver had been replaced by one of stone, occurs only in the later printed editions of these Chronicles; it is not found in the earlier Paris edition, and is wanting in every MS. I have had the opportunity of consulting, and especially in the fine transcript which forms a portion of the volume presented to Henry VI. by John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, preserved in the British Museum, as also in MSS. at Rouen. The evidence therefore to be derived from Du Moulin and the Chronicles printed by Le Mesgissier, appears to me inconclusive, and I am disposed to think the passage an interpolation arising from the unwarrantable surmise that, because the more precious memorial had disappeared, the effigy of stone which alone remained, was no portion of the original work, but had been placed there to supply the deficiency. With regard to the real date of the work, I would look specially to the style of art and decorative character, as displayed in the extensive series of regal effigies of the age of St. Louis in the crypts at St. Denis: their date may be fixed with confidence at about 1260, and from a careful comparison, I have no hesitation in asserting that the Rouen effigy must be placed at a period many years anterior; a conviction that the examination of other sculptured works in France, and of the effigy of King John at Worcester, has appeared to me sufficiently to corroborate. But a conclusive argument may, I conceive, be found with respect to the early age of this curious effigy, in the peculiarities of contemporary usage: at the period of Richard's decease, the singular custom of distributing the remains, as deposits in various places, which arose perhaps from the pious wish to secure the prayers of several congregations in favour of the soul of the deceased, was by no means unusual. A few instances may suffice to shew that in such cases the custom was to place at each spot where any portion of the departed had been destined to rest, an effigy, not always indeed identical as a portraiture, which in the present instance, as has been observed with regard to the effigy at Fontevrault, is not the case, but invariably a presumed representation of the personage commemorated. The interesting communication recently made to the Society by Mr. Hunter regarding the memorials of Queen Eleanor, affords an illustration of this, as far as I am aware, unique in England: her effigy and memorial in Lincoln Cathedral, where her viscera were interred, are described as identical with the exquisite work still preserved at Westminster; and it appears that in the church of the Black Friars, London, where her heart was deposited, a third similar memorial was erected. The remains of Marie de Bourbon were deposited at St. Yved de Braine in 1274, and an elaborate enamelled statue was placed to her memory, whilst a second but dissimilar effigy was to be seen in the church of St. Estienne at Dreux where her heart was interred. The same usage obtained in regard to Philippe le Hardi in 1285; his body was interred at St. Denis, and his viscera at Narbonne, an effigy being placed in both churches; and adjacent to the statue which forms the subject of my communication, was once seen at Rouen the duplicate effigy of Charles V. Instances might readily be multiplied, but the fact appears undeniable that by conventional usage a monumental effigy was placed at each spot where, by these singular dismemberments, a portion of the remains was deposited; and hence I am disposed to conclude, that the statue of Richard, considering the questionable evidence afforded by the printed chronicles, which, would lead to the surmise that it was a work of the age of St. Louis, and the marked dissimilarity apparent between the character of its execution, and that of works indubitably of the times of St. Louis, is in fact a work of the earlier years of the 13th century, and in all probability of the times of Archbishop Gautier, and the restoration of the cathedral after the conflagration. The costly shrine which the chronicles inform us was removed in 1250, I conceive to have been the receptacle only, wherein was enclosed the distinguished relic of the Lion-hearted Monarch whose effigy and memorial lay beneath, being an essential feature of the original monumental design.

I must beg your indulgence, and that of the Society, if an enthusiastic interest in works of this description has made me enter into details that may appear tedious or trivial: it has seemed to me, that to establish with the greatest possible precision the date of any work, which may serve as a type of art, is neither unprofitable, nor uninteresting to those who are occupied in researches into the progress of medieval sculpture or decoration.

There remain some perplexing discrepancies in relation to the decease and obsequies of Richard, that merit a passing notice. The numerous chronicles, of which many are closely contemporary with the event, vary in a most remarkable degree as to the exact date of his untimely end. A careful investigation, however, of the many conflicting statements sufficiently shews, that the wound was inflicted by the quarrel of Bertram le Gurdun from the walls of Chaluz, on the viith of the calends of April, 26th March; and that on the eleventh day, the viiith of the ides of April, namely April 6th, 1199, the death of Richard occurred, as stated by Hoveden, who is followed by the Annalist of Burton, Knighton, and others. A contemporary Necrology preserved in the archives of Rouen Cathedral confirms the last fact:

VIIL. Idus Aprilis, obiit Richardus illustris Rex Anglorum, qui redit huic ecclesia CCC modios vini de modiatione sua apud Rothomagum, pro restauratione dampnorum eidem ecclesiz illatorum a Rege Francie."

It is not a little curious that by one chronicler the scene of the fate of Richard has been placed, not in the Limosin, but under the walls of Chateau Gaillard, which was erected by him on the shores of the Seine: the relation occurs in Walter de Hemingford, it is considerably detailed, and, strange to say, the circumstances noticed accord with the peculiar position of that remarkable fortress: as, however, his record, however circumstantial, was not penned until more than a century had elapsed subsequent to the event, it merits no further observationg. With regard also to the place, where the heart of Richard was deposited, there existed a contradictory tradition as recorded by Stowe, who informs us, that on the north side of Allhallows Barking church, near the Tower of London, was some time built a fair chapel founded by King Richard I.; and that some have written that his heart was buried there under the high altar.

Note g. Gale, Hist. Angl. Seript. vol. ii. 550. Hemingford's tale has been adopted by a subsequent chronicler, Thomas Otterbourne, who lived early in the 15th century. Chron, Regum Angl. vol. i. 73, ed. Hearne. An allusion to it is made by Peter Langtoft in his Metrical Chronicle, printed by Hearne, where he speaks of the fatal event in the Limosin, "I wene it hate Chahalouns, or it hate Galiard, Outher the castelle or the toun, ther smyten was Richard." Rastell relates the death of King Richard as having occurred at "Castell Gayllarde." See the interesting account of the Chateau Gaillard, published by M. Deville, Rouen, 1829.

It is not uninteresting to know, incontrovertible as is the evidence of the chronicles which place the closing catastrophe of Richard's career at Chaluz, that local tradition fully accords with their testimony. My friend M. Allou, President of the Royal Society of French Antiquaries, a native of the Limosin, informs me that, having made a pilgrimage to the Castle of Chaluz, the very spot was pointed out to him, called la pierre de Maumont (de Malo monte) where immemorial tradition had recorded that Richard received his death wound from the shaft of the "Roi Gourdonh,"—it perhaps seemed to the vulgar that the Victor of Saladin could have fallen by the hand of none save an equal in regal dignity.

Note h. Description des Monumens observés dans le Departement de la Haute Vienne, par C. N. Allou, p. 356.

Nothing now remains in addition to this notice, except to mention the sepulchral inscription anciently affixed at Rouen, in a position adjoining the effigy of the King. I extract it from the fine copy of the Chronicles of Normandy, preserved among the Royal MSS. in the volume presented to Henry VI. by the Earl of Shrewsburyi. "Et sont intitulez ces vers de lui fais en vng tablel deuant sa Representacion en la dicte Eglise Nostre Dame de Rouen, au costé du Reuestuaire, et se commencent ainsi:

Epithafion inclite Recordacionis Ricardi condam Regis Anglie dicti corleonis [Epitaph of the famous record of Richard the Conda King of England called Lion Heart].

Aqualus cecidit Rex, regni cardo, Ricardus, [King Aqualus fell, the pivot of the kingdom, Richard]

Hiis ferus, (hiis) humilis, hiis agnus, hiis leo pardus [To the wild, to the humble, to the lamb, to the lion the leopard].

Casus erat lucis Chalus, per secula nomen [It was the case of Chalus, a name for centuries]

Ignotum fuerat, sed certum nominis omen [He had been unknown, but the omen of the name was certain]

Nunc patuit, res clausa fuit, sed luce cadente [Now it was clear, the thing was closed, but the light was falling]

Prodiit in lucem per casum lucis adempte. [He came into the light through the fall of light.]

Anno millesimo ducentesimo minus uno, [In the year one thousand two hundred less than one]

Ambrosii festo decessit ab orbe molesto. [He died on the feast of Ambrose from a troubled world]

Putans extra ducis sepelis rea terra Qualucis, [Thinking that outside the graves of the leader, the real land of Qualucis]

Nustria tuque Regis cor inexpugnabile Regis. [The unconquerable heart of the King is his constant companion]

Corpus das claudi sub marmore Fons Eberaudi. [You give the body of the lock under the marble of Fontevraud]

Sic loca per trina se spersit tanta ruina, [Thus he spread himself through three places in such great ruin]

Nec fuit hoc funus cui sufficeret locus unus, [Nor was this a funeral for which one place was sufficient]

Ejus vita brevis cunctis plangetur in evisk. [His short life will be mourned by all]

Note i. Royal MS. 15 E. VI. f. 446 ve. This inscription is given with some variations in the printed editions of the Chronicle of Normandy, and the six first lines will be found in Matthew Paris, A. D. 1199. According to the former, the first line commences thus, "Achalas cecidit Rex," but the reading, which doubtless is correct, is given by M. Paris, "Ad Chalus." The tenth line differs in the printed copy solely in the epithet "inestimabile," but the repetition of the word "Regis" is evidently a corrupt reading, which, where it occurs first, should be altered to "tegis." The previous line is equally incorrect, but the true reading is not so readily to be suggested; in the printed Chronicle it runs as follows: "Pictavis exta ducis sepelis rea terra caduci [The graves of the fallen leaders were painted on the ground]."

Note k. The feast of St. Ambrose was observed on the day before the nones, April 4th; but the decease of Richard occurred, as has been above stated, on April 6th, It must be remarked that the first six lines only of this inscription are given by Matthew Paris, and that the subsequent portion differs from the former in being written in Leonine verse; it seems therefore possible that the two portions were composed at different times, or by different versifiers, the later of whom followed the authority of some chronicle, which incorrectly recorded the 4th of April as the date of King Richard's demise.

I have the honour to be, dear Sir, Your obliged and faithful servant, Albert Way.