Jet

Jet is in Geology Artefacts.

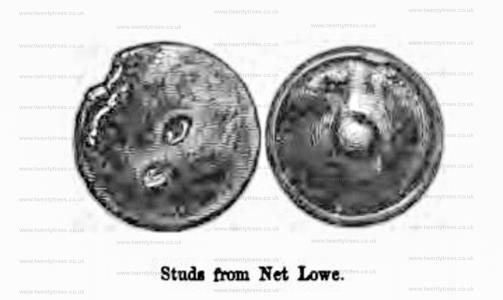

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the 4th of June, 1845, another large flat barrow was opened, which is situated upon the level summit of a hill upon Alsop Moor, known by the name of Net Lowe Hill [Map]. This barrow is about twenty-five yards in diameter, and not more than two feet in height; it was opened by cutting through it in different directions, so as to divide it into quarters. In each of these trenches, on approaching the centre, were found horses' teeth and an abundance of rats' bones; and in one of them a small piece of a coarse urn. In the centre of the tumulus was found a skeleton extended on its back at full length, and lying on a rather higher level than the surface of the natural soil; close to the right arm lay a large dagger of brass (broken in two by the weight of the superincumbent stones), with the decorations of its handle consisting of thirty rivets, and two pins of brass. In vol. i, plate 23, of Sir Richard Hoare's "Ancient Wiltshire" a dagger is engraved of a precisely similar character the number of rivets or studs and pins being exactly the same; close to this dagger were two highly-polished ornaments made from a kind of bituminous shale known in the south of England as Kimmeridge coal and equally well known to the archaeologist as the material of the coal money and of many other ancient British ornaments. Those in question are circular and moulded round the edges having a round elevation on the fronts to allow of two perforations which meet in an oblique direction on the back for the purpose of attaching the ornaments to some part of the dress or more probably to the dagger-belt of the chief with whose remains they were interred. In vol. 1, plate 34, of Sir Richard Hoare's book a similar ornament of jet is engraved, which is smaller, and does seem to have a moulding round the edge. It is a singular fact that, although the skeleton had evidently been never previously disturbed, the lower jaw lay at the feet of the body. Along with the above-mentioned articles were numerous fragments of calcined flint, and amongst the soil of the barrow were two rude instruments of the same.

Thomas Bateman 1845. The 12th of July, 1845, was devoted to the examination of a very large barrow [Map] [Note. Probably Ilam Tops Low [Map]] upon Ilam Moor, Staffordshire, which was found to be composed of alternate layers of earth and loose stones, some of considerable magnitude; these strata were clearly defined, there being no admixture of stone with the earthy layers, or of earth with the stony ones. At a distance of two yards from the centre, the cist, or vault, over which the mound had been originally piled, was discovered; it was excavated in a square form, about three feet deep in the solid rock, and was covered by several large blocks of stone, laid over the sides of the cist, the ends being raised, and meeting together so as to form a kind of cyclopean arch over the vault; these stones being removed, the cist was found to be filled with stones, amongst which were found the skull of a child, and a few scattered bones of a person of mature age; the floor of the cist was covered with a layer of charcoal, at least two inches in thickness, apparently produced from the combustion of oak timber; upon this stratum lay the head of a bull, un-burnt, and various other bones of the same animal, which were partially charred; near these, but not quite so low down, were the remains of two urns, one rudely, the other very neatly ornamented; a small brass pin pointed at each end; and a few bones of deer and dogs. Precisely in the centre of the tumulus, at about a yard from the surface, lay the skeleton of a dog, with which was a small chipping of flint; with this exception, nothing more was discovered in this very remarkable barrow, although no pains were spared in removing a large area of the artificial soil, until the rock came to view, upon which the whole fabric was raised. A somewhat similar instance of the discovery of a bulls head in a sepulchral cist is recorded as having been made in 1826 upon one of the cliffs at the bay of Worthbarrow, Dorsetshire, a place famed as the greatest depository in England for the well-known "Kimmeridge coal money" (See Miles's History of the Kimmeridge Coal Money, page 41.)

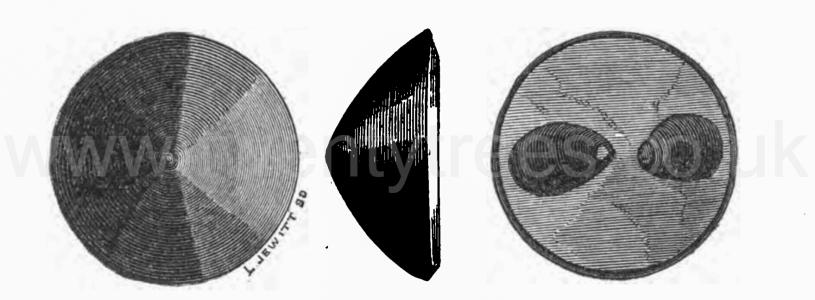

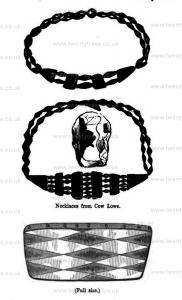

Thomas Bateman 1846. On the 29th of August 1846. The barrow at Cow Lowe [Map], near Buxton, was opened; although a little disturbed on the surface by the operations of stone-getters, the interments were quite intact. The number and importance of these deposits render needful a minute description of most of them, and a chronological arrangement will make each particular much more intelligible; by the latter system, we commence with the presumed primary interment, then tracing each succeeding one, in the order in which it was inhumed, instead of relating the particulars of each, in the rotation in which they were brought to light by the spade. Upon the floor of the barrow, which slightly exceeded the depth of four feet from the summit, was laid apparently the primitive interment, covered over with a large flat stone, but not inclosed in a cist; it was the body of a person of small stature, probably a female, with the knees contracted; it altogether rested upon a layer of calcined human bones, amongst which was found a bone pin, which had been perforated at the thicker end, but now broken, and part of a dog's head, also several horses' teeth; a few inches higher up, the whole of the centre of the tumulus was covered with human bones, unaccompanied by anything worthy of notice, if we except a few pieces of an urn, coarse, both in material and workmanship. The number of jaw-bones belonging to different skeletons in this part of the barrow was five, though it is probable that a greater number of individuals were here interred. About a foot higher than these, and slightly out of the centre of the barrow, was a small cist, made of stones set edgeways, which contained the bones of a female in the usual contracted position, with which were two sets of Kimmeridge coal beads (one hundred and seventeen in number), of very neat workmanship; the central ornaments are in this case made of the same material as the beads, though it will be remembered that, in the similar ornament found at Wind Lowe [Map], the central plates were of bone or ivory; a faintly marked diamond pattern is discernible upon the plates of shale; with these lay a fine instrument of calcined flint, of the circular-ended form; a few of the beads lay on the outside of the cist, where was part of the skeleton of a child, to whom possibly one set of beads might belong, or, what is more probable, that they were disturbed at the time of the construction of the hexagonal cell, which was placed partly upon the cist pertaining to the lady, at a slightly higher level; in it were deposited two skeletons, one above the other, much crushed up in order to accommodate them to the confined limits of the cell; with the lower one was a neatly ornamented urn of unbaked clay, much decayed and broken. The latest and most interesting interment, which may be attributed to the Romano-British period, or perhaps by some antiquaries to the early Saxon era, lay in the centre of the harrow, and about midway between the surface of the natural ground and the top of the former; the bones were mostly decayed, so much indeed, as to leave no trace except the teeth, and a small portion of the cranium; near which, probably about the neck, were two pins of gold, connected by a chain of the same, of remarkably neat design and execution; the heads of the pins contain a setting of many coloured glass, platted upon a chequered gold foil; close to them, and apparently having slipped off the chain, by a large bead of blue glass. The earth for a few feet from this place appeared to have been tempered with water, or puddled, at the time of the funeral, which gave it a very solid and undisturbed appearance; this, coupled with the absence of bones, makes it difficult to decide near what part of body the following articles were originally placed; they were about eighteen inches distant from the pins, which were certainly close to the head. These articles had been inclosed in a wooden box, made of ash plank half an inch in thickness, which was wrapped in a woollen cloth, the warp of which is perfectly visible; the hinges of this casket (two in number) are of brass, and were fastened with brass pins, which were clenched upon a piece of stout leather in the inside of the box; it was fastened by a brass hasp of similar type to the hinges, which received a small staple, to which was hung an iron padlock; it contained a small vessel of thick green glass, an ivory comb much decayed, some instruments of iron, a piece of perforated ivory, apparently the end of some utensil, which was encircled by a brass hoop at the time of its discovery, but which fell to dust on exposure, and a neck decoration of various pensile ornaments, eleven in number; the centre one is of blue porcelain or glass, with three serpents in white; it is retained in a setting of silver, with vandyked edges, on either side of this is a spiral wire bead of electrum, whilst the suit is made up of small circular pendants of silver, extremely thin, each having a level back and a convex front, and each stamped out of a separate piece; of these the number is eight, and with the exception of one, which has a beaded circle running round it, are all struck from the same die, a small flaw being visible on each; the box also contained a dog's or fox's tooth; and a short distance above the body, in the same tempered earth, lay a portion of the horn of the red deer. In various parts of the tumulus, but not in situations where they could be allotted with certainty to any of the interments, were found a scattered deposit of burnt bones, a bead of Kimmeridge coal, of more globular form than the others, much worn, a neat pin of bone, a pointed instrument of the same, apparently a lance-head, and the usual chippings of flint, and rats' bones.

Note. Necklace, possibly, from Cow Low on display at Weston Park Museum, Sheffield.

Kenslow Barrow. February 2nd. - The trenching of the barrow was continued, disclosing, near the centre, a depression below the natural level, which had contained the deposits formerly exhumed. In the course of the day pieces of three different urns were observed, one of coarse material and workmanship, another having been a neatly ornamented drinking cup, and lastly of a kiln-baked vessel of brick-red colour that had been made upon the wheel, and which must be therefore much more modem than the two former. There were also found three more of the bone crescents, part of a large ring of inferior jet or Kimmeridge coal, a small spatula of bone, probably used in the fabrication of pottery; a few instruments of flint, human and animal bones, both burnt and unbumt, and a tine from a stag's horn which has been roughly cut round, most probably with a flint saw.

Barrows near Arbor Low. On the 15th of March, we re-opened a barrow near the boundary of Middleton Moor, in the direction of Parcelly Hay [Note. Possibly Parsley Hay Barrow [Map]], which was unsuccessfully opened by Mr.W. Bateman on the 28th of July, 1824; nor did our researches lead to a more satisfactory result, as the entire mound seemed to have been turned over by deep ploughing by which the interments, consisting of two skeletons and a deposit of burnt bones, had been so dragged about as to present no characteristic worthy of observation. A neat whetstone was picked up amongst these ruins, and a carefully chipped leaf-shaped arrow-point of flint has since been found by ploughing across the barrow. About fifty yards South-east of the last, is another barrow of very small size, both as to diameter and height; so inconsiderable indeed are its dimensions, that it was quite overlooked in 1824. Fortunately the contents, with the exception of one skeleton that lay near the surface, had been enclosed in a cist, sunk a few inches beneath the level of the soil. As in the companion barrow, the skeleton near the top was dismembered by the plough, so that it afforded nothing worthy of notice - the original interment, however, which lay rather deeper, in a kind of rude cist or enclosure, formed by ten shapeless masses of limestone, amply repaid our labour. The persons thus interred consisted of a female in the prime of life, and a child of about four years of age; the former had been placed on the floor of the grave on her left side, with the knees drawn up; the child was placed above her, and rather behind her shoulders: they were surrounded and covered with innumerable bones of the water-vole, or rat, and near the woman was a cow's tooth, an article uniformly found with the more ancient interments. Round her neck was a necklace of variously shaped beads and other trinkets of jet and bone, curiously ornamented, upon the whole resembling those found at Cow Low [Map] in 1846, (Vestiges p. 92,) but differing from them in many details. The various pieces of this compound ornament are 420 in number, which unusual quantity is accounted for by the fact of 348 of the beads being thin laminae only; 54 are of cylindrical form, and the 18 remaining pieces are conical studs and perforated plates, the latter in some cases ornamented with punctured patterns. Altogether, the necklace is the most elaborate production of the pre-metallic period that I have seen. The skull, in perfect preservation, is beautiful in its proportions, and has been selected to appear in the Crania Britannica, as the type of the ancient British female. The femur measures 15¼ inches. The engraving represents the arrangement of the cist.

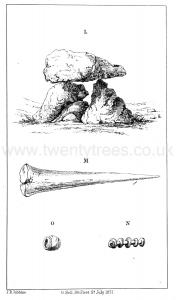

Diary of a Dean by Merewether. No. 13, of very trifling elevation compared with the depth at which the cist was found—3 feet. Many fragments of early pottery, teeth of red deer and ox, a bead (O) of jet or Kimmeridge coal, and nine very smooth gravel pebbles, probably for slinging. The cist, filled with burnt human bones, but without an urn, was 3 ft. 6 in. long by ? ft. wide, and 2 ft. deep.

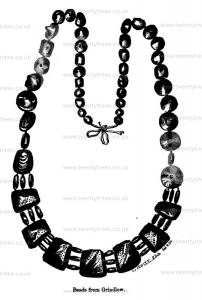

Over Haddon. On the 30th of April a barrow [Map] [Burton Moor Barrow [Map]] near Over Haddon, in land called Grindlow, was examined as completely as the meeting of three walls on its summit would allow. It had been much mutilated; but fortunately the primitive interments lay too deep to receive injury from the labours of those in search of stone, by whom an important interment of secondary date had been destroyed. The original deposit had been made on the rock a little below the natural surface, and about 5 feet from the top of the mound; it comprised three skeletons, laid in the usual contracted position, two of which were females; with them were one or two rude instruments of flint, and a fine collection of jet ornaments, 73 In number, which form a very handsome necklace. Of these 26 are cylindrical beads, 39 are conical studs, pierced at the back by two holes meeting at an angle in the centre; and the remaining 8 are flat dividing plates, ornamented in the front with a punctured chevron pattern, superficially drilled in the jet; 7 of them are laterally perforated with three holes, to admit of their being connected by a triple row of the cylindrical beads, whilst the 8th, which is of bone, ornamented in the same style, has nine holes at one side, which diminish to three on the other by being bored obliquely. Above these bodies, which were covered with stone, the mound was of unmixed earth, very compact and clayey, and between the stone and earth were many pieces of calcined bone, and numerous splinters of the leg bones of large animals, some of which are likely to have been used as points for weapons. In the earth near the summit of the barrow were some relics of a later interment, probably of a distinguished Saxon, with whom had been deposited a circular enamel, of which only the silver plated frame remained, the latter is engrailed on the front, and engraved with a lozengy pattern round the edge; and a bowl of thin bronze, very neatly made, with a simple hollow moulding round the edge, which when complete was 7 inches diameter, and appears to have had two handles soldered or cemented to the sides. The bowl was broken when found, and no handles were discovered; but it is probable that both they and some other ornaments, as well as another of the bone plates with 9 perforations, which is wanting to complete the necklace, would have been found if the triple wall could have been removed, as the point of junction was directly over the place where the interments lay, which were exhumed by a dangerous undercutting.

Chelmorton. On the 5th of July we resumed the examination of the barrow at Nether Low [Map], and found at the west side about five yards from the centre, four interments, three of which were placed in angle of a shallow depression in the rock, of irregular form. The most important of these was the skeleton of a middle aged man, lying contracted in the western angle, having beneath the head, and in contact with the skull, a beautiful leaf-shaped dagger of white flint, 4½ inches long, with the narrower half curiously serrated. A few inches from this unique weapon, was a plain but neat spear head of white flint. In a joint of the rock at a right angle with this interment, was a slender skeleton, probably of a female in the prime of life, accompanied by a prism-shaped piece of white flint, a piece of hematite, a boar's tusk, and a large globular bead of jet; the last found close to the neck.

The third skeleton was that of a much younger subject, and lay on the rock a little nearer the centre; it was not provided with implements, but between it and the others was a single piece of a calcined human skull. They were all about 4 feet from the top of the barrow.

Another skeleton was discovered about two feet from the surface, in a cist covered by a large flat stone and constructed across the joint of rock occupied by the female skeleton; it was accompanied by stags' horns of large size, and an arrow point of grey flint; and appeared to be the body of a person 17 or 18 years old.

In another cutting, near the outside, we found the remains of an infant, and a very neat instrument of white flint of uncertain use.

Castern. On the afternoons of the 18th and 19th of July, we opened a barrow between Bitchin Hill [Map] and Castern [Map], eighteen yards diameter, and only about eighteen inches high, a great deal of the top having been removed for the sake of the stone. On the first day we removed a considerable area from the centre towards the south-east, the whole of which was strewed with human and animal bones, and other trifling remains common in most barrows. Amongst them was the decayed skeleton of a young person. The next day we continued our excavation in an opposite direction, where, about two yards from the middle of the barrow, was an oval grave, seven feet long by 3½ feet wide, cut in the rock to the depth of about two feet. It was filled with earth and stones, covering a large skeleton lying at the bottom, on its lefl side, in the usual contracted posture, with the head to the north. Near the shouders was a large and highly-polished stud, of jet or coal, 1¾ inches diameter, with two oblique holes meeting at an angle behind. A small piece of calcined flint was also found near the same place.

The femur measures nineteen inches. In the grave were many rats' bones, and above it were the remains of a young person, with bits of earthenware and burnt flints.

Hill Head. On the 5th of June, we opened a barrow [Hill Head Barrow [Map]] on the Hill Head, an eminence in the neighbourhood of the last. The mound is about twelve yards across, and presents the appearance of having been much reduced, the height being nowhere more than eighteen inches. The centre had been disturbed with the effect of displacing the skeletons of three or four persons and some calcined bones; the earth around did not appear to have been moved, as masses of rats' bones occupied their original level. Notwithstanding the unfavourable condition of the barrow, we collected 81 jet ornaments, composing a handsome necklace that had accompanied one of the skeletons, they comprise 53 cylindrical, and 11 flat beads, 12 conical studs, and five out of the six dividing plates requisite to form the decoration: the plates are plain, and the centre pair are perforated for eight beads to go between. It is likely that many more of the very small flat beads would have been found if the tumulus had not been before disturbed; those that were found being collected with much trouble from an area of many feet, instead of lying near the head of their owner.

Monsal Dale. On the same afternoon, we began an examination of a large mutilated flat-topped barrow [Hay Top Barrow [Map]], twenty yards diameter and four feet high, on the summit of a hill called Hay Top, overlooking the manufacturing colony of Cressbrook. The mound is piled upon a naturally elevated rock, so as not to present more than two feet of accumulated material in the middle, where we began to dig, finding remains of many individuals, from infants to adults of large stature (an imperfect femur, broken off below the neck, measuring near nineteen inches), but all were in disorder except one skeleton, which appeared to lie on its left side in the centre; it was, however, so much surrounded by other bones as to be rather difficult to identify, and, from the same confusion, we cannot positively assign all the following articles to it, though there is scarcely a doubt that the flints and bone ornament were buried with it: - The objects referred to, are ten jet beads of the three common shapes, several flints, including three thick arrow points, and a curious bone ornament, with a hole for suspension round the neck, where it was found, not unlike a seal with a rectangular face. The skeleton, from the slenderness of the bones, was judged to be that of a female. We casually found pieces of two vessels, a polecat's skull, and many bones of the water-vole.

Frederick Lukis 1865. When we were about quitting Buxton, I was beginning to make a host of friends amongst the farmers and labourers, and from them obtained lots of information; this led me in my rambles over the spot where I was informed that two stone knives had been picked up (one of which was sent to London, and the other given to Mr. Bateman). I was climbing hill after hill without any positive certainty of meeting with anything of interest, when suddenly I saw, whilst crossing a wheat field, unmistakable signs of a Barrow [Map] [Gospel Hillock Barrow [Map]]. I called on the farmer, Mr. Charles Holmes, and on pointing to the heap of stones he at once exclaimed, 'Oh, sir, I wish they were out of that, for when ploughing that field we are sadly plagued by them.' I then asked to be allowed to make a small hole with a spade in the mound; this, he said, he could not grant, but added that if I were to call on the Rev. Mr. Pickford, the owner of the property, he doubtless would grant me permission to do so. After a walk to the house, and explaining the object of my visit, Mr. Pickford very kindly gave me leave on condition of levelling the ground again.

The next day we repaired to the place, and shortly after we were met by Miss Pickford, his sister, who most obligingly gave us the history of the mound in question. She narrated as follows 'The place was called from time immemorial "The Gospel Hillock;" the mound was held in considerable estimation and reverence, as its name imports, for here, in perilous times, people repaired for religious purposes, and holy persons preached and read the scriptures, whence it had obtained the name by which it was known.' We of course assented with her on its sacred character, and we thanked her for the valuable information we had obtained, and after her departure we commenced our operations with spade and pick, not doubting that ere long by these means the exact nature of 'Gospel Hillock' would tell a different tale as to its origin and purpose.

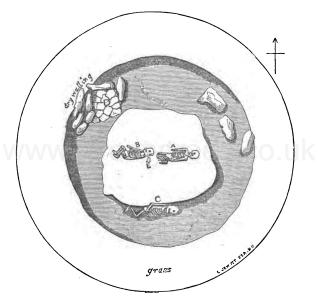

We commenced digging over that part marked a on the plan, and after proceeding with the usual caution always necessary in working on a low barrow, our spade soon produced the signs of interment - a few human bones were perceptible, which doubtless belonged to some skeleton not far distant. In a short time at the depth of a foot a skeleton was discovered, lying partly on its back with its legs evidently doubled up. We were the more surprised at finding this subject lying upon a flat surface or level of a stone, apparently of large dimensions. The very solid floor on which this individual lay induced us to extend out search, in order to determine its extent; in doing this we discovered several conical studs of polished kimmeridge coal, drilled with two connecting holes for being strung or fastened in the usual method of that period. The skull was evidently towards the east, and the cervical vertebræ, ribs, and bones of the arms, mixed up with the legs and the fingerbones, indicating that the body had not been stretched out, but rather in a doubled up position.

In proceeding to remove the earth in a westerly direction, I suddenly touched the skull of another individual lying in nearly the same position, and ex tended towards the western part of the large stone. Whilst cautiously clearing the earth away from the head, I fortunately perceived the keen edge of a flint celt, at E, (shown on the accompanying engraving), which lay on the stone and near the south side of the shoulder of B. I could scarcely express to my companions the delight I then felt, and as neither of them were acquainted with the nature of a celt, they were the more astonished at the cause of my excitement. Before removing the instrument I endeavoured to explain to them what their uses were, among all nations ancient and modern, and tried to answer a hundred questions which the subject gave rise to. After a very learned lecture on the celt, I gently extracted the object of my joy.

This little incident caused some delay in our operations, and after having exposed the second skeleton, we cleared the edge of the stone at c, and there found a third individual lying in the trench near it, and partly touching the large stone, which we now found measured 7 ft. 8 in. in diameter by 7 ft. 3 in. wide. Fragments of bones, teeth, and a few flint chippings were found also.

Note A. D, the pick-axe struck upon a largish stone, and in pursuing our work in that direction, we came upon a perfect little chamber without any covering stone, and on working down to the same level as our trough we came upon a pavement of flattish stones, on which were laid two skeletons; the western limit being closed up by stones and dry walling. Flint flakes were more numerous here, and against the northern props there was a neat urn, or drinking vessel, of reddish clay (but in the interior of a dark colour). On the external surface were eight circular rows of vertical indents, somewhat rudely engraved. The height was about seven inches, and it was not inelegant in its out line. This urn is here engraved.

After completing the excavation round the central stone we left off our work, intending on the morrow, if possible, to raise the flat suspicious base on which the skeletons reposed, and ascertain if it might not prove a covering to some more interesting deposit. The weather, however, was too wet and stormy for our work on that day.

On the following morning we repaired to the spot with that intention, but on arriving there found that the whole had been recovered and filled, by order of Mr. Pickford - that gentleman having unfortunately concluded that we were not to return to "Gospel Hillock" and restore it to its former outline as we had promised to do.

In forwarding these few notes and observations, I beg to say that they were written by Captain Lukis for insertion in my own collectanea, but if you consider them worthy of a place in the "Reliquary," it will afford him some pleasure to know that his visit to Derbyshire was not in vain.

The Grange, Guernsey.