Biography of Percy Bysshe Shelley 1792-1822

Paternal Family Tree: Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley 1792-1822 is in Poets.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. SHELLEY, PERCY BYSSHE (1792–1822), English poet, was born on the 4th of August 1792 was born at Field Place, near Horsham, Sussex. He was the eldest child of Timothy Shelley (1753–1844) (age 38), M.P. for Shoreham, by his wife Elizabeth, daughter of Charles Pilfold, of Effingham, Surrey. His father (age 38) was the son and heir of Sir Bysshe Shelley (age 61), Bart. (d. 1815), whose baronetcy (1806) was a reward from the Whig party for political services. Sir Bysshe's (age 61) father Timothy had emigrated to America, and he himself had been born in Newark, New Jersey; but he came back to England, and did well for himself by marrying successively two heiresses, the first, the mother of Timothy (age 38), being Mary Catherine, daughter of the Rev. Theobald Michell of Horsham. He was a handsome man of enterprising and remarkable character, accumulated a vast fortune, built Castle Goring, and lived in sullen and penurious retirement in his closing years. None of his talent seems to have descended to his son Timothy (age 38), who, except for being of a rather oddly self-assertive character, was indistinguishable from the ordinary run of commonplace country squires. The mother of the poet is described as beautiful, and a woman of good abilities, but not with any literary turn; she was an agreeable letter-writer. The branch of the Shelley family to which the poet Percy Bysshe belonged traces its pedigree to Henry Shelley, of Worminghurst, Sussex, who died in 1623. These Worminghurst or Castle Goring Shelleys are of the same stock as the Michelgrove Shelleys, who trace up to Sir William Shelley, judge of the common pleas under Henry VII., thence to a member of parliament in 1415, and to the reign of Edward I., or even to the epoch of the Norman Conquest. The Worminghurst branch was a family of credit, but not of special distinction, until its fortunes culminated under the above-named Sir Bysshe.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. 1798. At the age of six he [Percy Bysshe Shelley] was sent to a day school at Warnham, kept by the Rev. Mr Edwards; at ten to Sion House School, Brentford, of which the principal was Dr Greenlaw, while the pupils were mostly sons of local tradesmen;

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. [Percy Bysshe Shelley] ... at twelve (or immediately before that age, on the 29th of July 1804) to Eton. The headmaster of Eton, up to nearly the close of Shelley's sojourn in the school, was Dr Goodall, a mild disciplinarian; it is therefore a mistake to suppose that Percy (unless during his very brief stay in the lower school) was frequently flagellated by the formidable Dr Keate, who only became headmaster after Goodall. Shelley was a shy, sensitive, mopish sort of boy from one point of view - from another a very unruly one, having his own notions of justice, independence and mental freedom; by nature gentle, kindly and retiring - under provocation dangerously violent. He resisted the odious fagging system, exerted himself little in the routine of school-learning, and was known both as "Mad Shelley" and as "Shelley the Atheist." Some writers try to show that an Eton boy would be termed atheist without exhibiting any propensity to atheism, but solely on the ground of his being mutinous. However, as Shelley was a declared atheist a good while before attaining his majority, a shrewd suspicion arises that, if Etonians dubbed him atheist, they had some relevant reason for doing so.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Shelley entered University College, Oxford, in April 1810, returned thence to Eton, and finally quitted the school at midsummer, and commenced residence in Oxford in October. Here he met a young Durham man, Thomas Jefferson Hogg, who had preceded him in the university by a couple of months; the two youths at once struck up a warm and intimate friendship. Shelley had at this time a love for chemical experiment, as well as for poetry, philosophy, and classical study, and was in all his tastes and bearing an enthusiast. Hogg was not in the least an enthusiast, rather a cynic, but he also was a steady and well-read classical student. In religious matters both were sceptics, or indeed decided anti-Christians; whether Hogg, as the senior and more informed disputant, pioneered Shelley into strict atheism, or whether Shelley, as the more impassioned and unflinching speculator, outran the easy-going jeering Hogg, is a moot point; we incline to the latter opinion. Certain it is that each egged on the other by perpetual disquisition on abstruse subjects, conducted partly for the sake of truth and partly for that of mental exercitation, without on either side any disposition to bow to authority or stop short of extreme conclusions. The upshot of this habit was that Shelley and Hogg, at the close of some five months of happy and uneventful academic life, got expelled from the university.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Shelley - for he alone figures as the writer of the "little syllabus," although there can be no doubt that Hogg was his confidant and coadjutor throughout - published anonymously a pamphlet or flysheet entitled The Necessity of Atheism, which he sent round to bishops and all sorts of people as an invitation or challenge to discussion. It amounted to saying that neither reason nor testimony is adequate to establish the existence of a deity, and that nothing short of a personal individual self-revelation of the deity would be sufficient. The college authorities heard of the pamphlet, identified Shelley as its author, and summoned him before them - "our master, and two or three of the fellows." The pamphlet was produced, and Shelley was required to say whether he had written it or not. The youth declined to answer the question, and was expelled by a written sentence, ready drawn up. Hogg was next summoned, with a result practically the same. The precise details of this transaction have been much controverted; the best evidence is that which appears on the college records, showing that both Hogg and Shelley (Hogg is there named first) were expelled for "contumaciously refusing to answer questions," and for "repeatedly declining to disavow" the authorship. Thus they were dismissed as being mutineers against academic authority, in a case pregnant with the suspicion - not the proof - of atheism; but how the authorities could know beforehand that the two undergraduates would be contumacious and stiff against disavowal, so as to give warrant for written sentences ready drawn up, is nowhere explained. Possibly the sentences were worded without ground assigned, and would only have been produced in terrorem had the young men proved more malleable. The date of this incident was the 25th of March 1811.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. After 25 Mar 1811. Shelley and Hogg came up to London, where Shelley was soon left alone, as his friend went to York to study conveyancing. Percy and his incensed father did not at once come to terms and for a while he had no resource beyond pocket-money saved up by his sisters (four in number altogether) and sent round to him, sometimes by the hand of a singularly pretty school-fellow, Miss [his future wife] Harriet Westbrook, daughter of a retired and moderately rich hotel-keeper. Shelley, in early youth, had a somewhat "priggish" turn for moralizing and argumentation, and a decided mania for proselytizing; his school-girl sisters, and their little Methodist friend Miss Westbrook, aged between fifteen and sixteen, must all be enlightened and converted to anti-Christianity. He therefore cultivated the society of Harriet, calling at the house of her father, and being encouraged in his assiduity by her much older sister Eliza. Harriet not unnaturally fell in love with him; and he, though not it would seem at any time ardently in love with her, dallied along the Bowery pathway which leads to sentiment and a definite courtship. This was not his first love-affair; for he had but a very few months before been courting his cousin Miss Harriet Grove, who, alarmed at his heterodoxies, finally broke off with him - to his no small grief and perturbation at the time. It is averred, and seemingly with truth, that Shelley never indulged in any sensual or dissipated amour; and, as he advances in life, it becomes apparent that, though capable of the passion of love, and unusually prone to regard with much effusion of sentiment women who interested his mind and heart, the mere attraction of a pretty face or an alluring figure left him unenthralled.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. After Aug 1811. [his future wife] Harriet Shelley was not only beautiful; she was amiable, accommodating, adequately well educated and well bred. She liked reading, and her reading was not strictly frivolous. But she could not (as Shelley said at a later date) "feel poetry and understand philosophy." Her attractions were all on the surface; there was (to use a common phrase) "nothing particular in her." For nearly three years Shelley and she led a shifting sort of life upon an income of £400 a year, one-half of which was allowed (after his first severe indignation at the mésalliance was past) by Mr [his father] Timothy Shelley (age 57), and the other half by Mr Westbrook. The couple left Edinburgh for York and the society of Hogg; broke with him upon a charge made by Harriet, and evidently fully believed by Shelley at the time, that, during a temporary absence of his upon business in Sussex, Hogg had tried to seduce her (this quarrel was entirely made up at the end of about a year); moved off to Keswick in Cumberland, where they received kind attentions from Southey (age 36), and some hospitality from the duke of Norfolk (age 65), who, as chief magnate in the Shoreham region of Sussex, was at pains to reconcile the father and his too unfilial heir;

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. After a while Percy was reconciled to his father, revisited his family in Sussex, and then stayed with a cousin in Wales. Hence he was recalled to London by Miss Harriet Westbrook, who wrote complaining of her father's resolve to send her back to her school, in which she was now regarded with repulsion as having become too apt a pupil of the atheist Shelley. He replied counselling resistance. "She wrote to say" (these are the words of Shelley in a letter to Hogg, dating towards the end of July 1811) "that resistance was useless, but that she would fly with me, and threw herself upon my protection." Shelley, therefore, returned to London, where he found Harriet agitated and wavering; finally they agreed to elope, travelled in haste to Edinburgh, and there, on the 28th of August, were married with the rites of the Scottish Church. Shelley, it should be understood, had by this time openly broken, not only with the dogmas and conventions of Christian religion, but with many of the institutions of Christian polity, and in especial with such as enforce and regulate marriage; he held - with William Godwin (age 55) and some other theorists - that marriage ought to be simply a voluntary relation between a man and a woman, to be assumed at joint option and terminated at the after-option of either party. If, therefore, he had acted upon his personal conviction of the right, he would never have wedded Harriet, whether by, Scotch, English or any other law; but he waived his own theory in favour of thee consideration that in such an experiment the woman's stake, land the disadvantages accruing to her, are out of all comparison with the man's. His conduct, therefore, was so far entirely honourable; and, if it derogated from a principle of his own (a principle which, however contrary to the morality of other people, was and always remained matter of genuine conviction on his individual part), this was only in deference to a higher and more imperious standard of right.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Sep 1811 to Feb 1813. [Percy Bysshe Shelley] ... sailed thence to Dublin, where Shelley was eager, and in some degree prominent, in the good cause of Catholic emancipation, conjoined with repeal of the union; crossed to Wales, and lived at Nant-Gwillt, near Rhayader, then at Lynmouth [Map] in Devonshire, then at Tanyrallt in Carnarvonshire. All this was between September 1811 and February 1813. At Lynmouth an Irish servant of Shelley's was sentenced to six months' imprisonment for distributing and posting up printed papers, bearing no printer's name, of an inflammatory or seditious tendency - being a Declaration of Rights composed by the youthful reformer, and some verses of his named The Devil's Walk. At Tanyrallt Shelley was (according to his own and Harriet's account, confirmed by the evidence of Miss Westbrook, the elder sister, who continued an inmate in most of their homes) attacked on the night of 26th February by an assassin who fired three pistol-shots. It was either a human assassin or (as Shelley once said) " the devil." The motive of the attack was undefined; the fact of its occurrence was generally disbelieved, both at the time and by subsequent inquirers. Shelley was full of wild unpractical notions; he dosed himself occasionally with laudanum as a palliative to spasmodic pains; he was given to strange assertions and romancing narratives (several of which might properly be specified here but for want of space), and was not incapable of conscious fibbing. His mind no doubt oscillated at times along the line which divides sanity from insane delusion. It is now, however, at last proved that he did not invent such a monstrous story to serve a purpose. The Century Magazine for October 1905 contained an article entitled "A Strange Adventure of Shelley's," by Margaret L. Croft, which shows that a shepherd close to Tanyrallt, named Robin Pant Evan, being irritated by some well-meant acts of Shelley in terminating the lives of dying or diseased sheep, did really combine with two other shepherds to scare the poet, and Evan was the person who played the part of "assassin." He himself avowed as much to members of a family, Greaves, who were living at Tanyrallt between 1847 and 1865. This was the break-up of the residence of the Shelleys at Tanyrallt; they revisited Ireland, and then settled for a while in London.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. 1812. In Pisa he [Percy Bysshe Shelley] formed a sentimental intimacy with the Contessina Emilia Viviani, a girl who was pining in a convent pending her father's choice of a husband for her; this impassioned but vague and fanciful attachment - which soon came to an end, as Emilia's character developed less favourably in the eyes of her Platonic adorer - produced the transcendental love-poem of Epipsychidion in 1821. In Ravenna the scheme of the quarterly magazine the Liberal was concerted by Byron and Shelley, the latter being principally interested in it with a view to benefiting Leigh Hunt by such an association with Byron. In Pisa Byron and Shelley were very constantly together, having in their company at one time or another Shelley's cousin and schoolfellow Captain Thomas Medwin (1788–1869), Lieutenant Edward Elliker Williams (1793–1822) and his wife, to both of whom the poet was very warmly attached, and Captain Edward John Trelawny, the adventurous and romantic-natured seaman, who has left important and interesting reminiscences of this period. Byron admired very highly the generous, unworldly and enthusiastic character of Shelley, and set some value on his writings; Shelley half-worshipped Byron as a poet, and was anxious, but in some conjunctures by no means able, to respect him as a man. In Pisa he knew also Prince Alexander Mavrocordato, one of the pioneers of Grecian insurrection and freedom; the glorious cause fired Shelley, and he-wrote the drama of Hellas (1821).

In Jun 1813 [his daughter] Ianthe Eliza Shelley was born to Percy Bysshe Shelley and [his wife] Harriet Westbrook.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Here, in June 1813, [his wife] Harriet gave birth to her daughter [his daughter] Ianthe Eliza (she married a Mr Esdaile, and died in 1876). Here also Shelley brought out his first poem of any importance, Queen Mab; it was privately printed, as its exceedingly aggressive tone in matters of religion and morals would not allow of publication. In July the Shelleys took a house at Bracknell near Windsor Forest, where they had congenial neighbours, Mrs Boinville and her family.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. It was towards May 1814 that Shelley first saw [his future wife] Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (age 16) as a grown-up girl (she was well on towards seventeen); he instantly fell in love with her, and she with him. Just before this, on the 24th of March, Shelley had remarried [his wife] Harriet in London, apparently with a view to strengthening his position in his relations with his father as to the family property; but, on becoming enamoured of Mary, he seems to have rapidly made up his mind that Harriet should not stand in the way. She was at Bath while he was in London. They had, however, met again in London and come to some sort of understanding before the final crisis arrived-Harriet remonstrating and indignant, but incapable of effective resistance-Shelley sick of her companionship, and bent upon gratifying his own wishes, which as we have already seen were not at odds with his avowed principles of conduct. For some months past there had been bickering's and misunderstandings between him and Harriet, aggravated by the now detested presence of Miss Westbrook in the house; more than this cannot be said, and it seems dubious whether more will be hereafter known. Shelley, and not he alone, alleged grave misdoing on Harriet's part - perhaps mistakenly.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. The upshot came on the 28th of July, when Shelley aided [his future wife] Mary (age 16) [Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 16)] to elope from her father's house, Claire Clairmont (age 16) deciding to accompany them. They crossed to Calais, and proceeded across France into Switzerland. [his future father-in-law] Godwin (age 58) and his wife were greatly incensed. Though he and Mary Wollstonecraft had entertained and avowed bold opinions regarding the marriage-bond, similar to Shelley's own, and had in their time acted upon these opinions, it is not clearly made out that Mary Godwin had ever been encouraged by paternal influence to think or do the like. Shelley and she chose to act upon their own likings and responsibility - he disregarding any claim which Harriet had upon him, and Mary setting at nought her father's authority. Both were prepared to ignore the law of the land and the rules of society. The three young people returned to London in September.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. In the following January 1815 Sir Bysshe Shelley (age 83) died, and Percy, who had, lately been in great money-straits, became the immediate heir to the entailed property inherited by his father Sir Timothy (age 61). This entailed property seems to have been worth £6000 per annum, or little less. There was another very much larger property which Percy might shortly before have secured to himself, contingently upon his father's death, if he would have consented to put it upon the same footing of entail; but this he resolutely refused to do, on the professed ground of his being opposed upon principle to the system of entail; therefore, on his grandfather's death the larger property passed wholly away from any interest which Percy might have had in it, in use or in expectancy. He now came to an understanding with his father as to the remaining entailed property; and, giving up certain future advantages, he received henceforth a regular income of £1000 a year. Out of this he assigned £200 a year to Harriet, who had given birth in November to a son, [his son] Charles Bysshe (he died in 1826). Shelley, and Mary as well, were on moderately good terms with Harriet, seeing her from time to time. His peculiar views as to the relations of the sexes appear markedly again in his having (so it is alleged) invited Harriet to return to his and Mary's house as a domicile; a curious arrangement which of course did not take effect. He had, undoubtedly, while previously abroad with Mary, invited Harriet to stay in their immediate neighbourhood. Shelley and Mary (who was naturally always called Mrs Shelley) now settled at Bishopgate, near Windsor Forest; here he produced his first excellent poem, Alastor, or the Spirit of Solitude, which was published soon afterwards With a few others. Thomas Love Peacock was one of his principal associates at Bishopgate.

On 06 Jan 1815 [his grandfather] Bysshe Shelley 1st Baronet (age 83) died. His son [his father] Timothy Shelley 2nd Baronet (age 61) succeeded 2nd Baronet Shelley of Castle Goring in Sussex.

In Nov 1815 [his son] Charles Bysshe Shelley was born to Percy Bysshe Shelley and [his wife] Harriet Westbrook.

On 09 Nov 1815 [his wife] Harriet Westbrook committed suicide by drowning in the The Serpentine, Hyde Park.

Around 18 Aug 1816 George "Lord Byron" 6th Baron Byron (age 28), Percy Bysshe Shelley, his future wife [his future wife] Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 18), John William Polidori (age 20) were staying at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Sep 1816. The return of the Shelleys was closely followed by two suicides - first that of Fanny Wollstonecraft (already referred to), and second that of [his former wife] Harriet Shelley, who on the 9th of November drowned herself in the Serpentine. The body was not found until the 10th of December. The latest stages of the lovely and ill-starred Harriet's career have never been very explicitly recorded. It seems that she formed a connexion with some gentleman from whom circumstances or desertion separated her, that her habits became intemperate, and that she was treated with contumelious harshness by her sister during an illness of their father. She had always had a propensity (often laughed at in earlier and happier days) to the idea of suicide, and she now carried it out in act-possibly without anything which could be regarded as an extremely cogent predisposing motive, although the total weight of her distresses, accumulating within the past two years and a half, was beyond question heavy to bear. Shelley, then at Bath, hurried up to London when he heard of Harriet's death, giving manifest signs of the shock which so terrible a catastrophe had produced on him. Some self-reproach must no doubt have mingled with his affliction and dismay; yet he does not appear to have considered himself gravely in the wrong at any stage in the transaction, and it is established that in the train of quite recent events which immediately led up to Harriet's suicide he had borne no part. This was the time when Shelley began to see a great ideal of Leigh Hunt, the poet and essayist, editor of the Examiner; they were close friends, and Hunt did something to uphold the reputation of Shelley as a poet-which, we may here say once for all, scarcely obtained any public acceptance or solidity during his brief lifetime.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. [Percy Bysshe Shelley] The death of Harriet having removed the only obstacle to a marriage with Mary Godwin (age 19), the wedding ensued on the 30th of December 1816, and the married couple settled down at Great Marlow in Buckinghamshire.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Their [Percy Bysshe Shelley and [his wife] Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 19)] tranquillity was shortly disturbed by a Chancery suit set in motion by Mr Westbrook, who asked for the custody of his two grandchildren, on the ground that Shelley had deserted his wife and intended to bring up his offspring in his own atheistic and anti-social opinions. Lord Chancellor Eldon (age 65) delivered judgment on the 27th of March 1817. He held that Shelley, having avowed condemnable principles of conduct, and having fashioned his own conduct to correspond, and being likely to inculcate the same principles upon his children, was unfit to have the charge of them. He appointed as their curator Dr Hume, an orthodox army physician, who was Shelley's own nominee. The poet had to pay for the maintenance of the children a sum which stood eventually at £120 per annum; if it was at first (as generally stated) £200, that was no more than what he had previously allowed to Harriet.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. In 1818 the Shelleys [Percy Bysshe Shelley and [his wife] Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 20)] - always nearly with Miss Clairmont (age 19) in their company - were in Milan, Leghorn, the Bagni di Lucca, Venice and its neighbourhood, Rome, and Naples; in 1819 in Rome, the vicinity of Leghorn, and Florence (both their infants were now dead, but a third was born late in 1819, Percy Florence Shelly, who in 1844 inherited the baronetcy); in 1820 in Pisa the Bagni di Pisa (or di San Giuliano), and Leghorn; in 1821 in Pisa and with Byron in Ravenna; in 1822 in Pisa and on the Bay of Spezia, between Lerici and Sari Terenzio. The incidents of this period are but few, and of no great importance apart from their bearing upon the poet's writings. In Leghorn he knew Mr and Mrs Gisborne, the latter a once intimate friend of Godwin; she taught Shelley Spanish, and he was eager to promote a project for a steamer to be built by her son by a former marriage, the engineer Henry Reveley; it would have been the first steamer to navigate the Gulf of Lyons.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. This is the last incident of marked importance in the perturbed career of Shelley; the rest relates to the history of his mind, the poems which he produced and published, and his changes of locality in travelling. The first ensuing poem was The Revolt of Islam, referred to near the close of this article. In March 1818, after an illness which he regarded (rightly or wrongly) as a dangerous pulmonary attack, Shelley, with his wife, their two infants William and Clara, and Miss Clairmont (age 19) and her baby Allegra, went off to Italy, where the short remainder of his life was passed. Allegra was soon sent on to Venice, to her father, who, ever since parting from Miss Clairmont in Switzerland, showed a callous and unfeeling determination to see and know no more about her.

On 12 Nov 1819 [his son] Percy Florence Shelley 3rd Baronet was born to Percy Bysshe Shelley and [his wife] Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 22).

Adonais by Percy Bysshe Shelley. In Apr 1821 Percy Bysshe Shelley composed his elegy to John Keats. The poem is a 495 line pastoral elegy in 55 Spenserian stanzas.

I

I weep for Adonais-he is dead!

Oh, weep for Adonais! though our tears

Thaw not the frost which binds so dear a head!

And thou, sad Hour, selected from all years

To mourn our loss, rouse thy obscure compeers,

And teach them thine own sorrow, say: "With me

Died Adonais; till the Future dares

Forget the Past, his fate and fame shall be

An echo and a light unto eternity!"

II

Where wert thou, mighty Mother, when he lay,

When thy Son lay, pierc'd by the shaft which flies

In darkness? where was lorn Urania

When Adonais died? With veiled eyes,

'Mid listening Echoes, in her Paradise

She sate, while one, with soft enamour'd breath,

Rekindled all the fading melodies,

With which, like flowers that mock the corse beneath,

He had adorn'd and hid the coming bulk of Death.

III

Oh, weep for Adonais-he is dead!

Wake, melancholy Mother, wake and weep!

Yet wherefore? Quench within their burning bed

Thy fiery tears, and let thy loud heart keep

Like his, a mute and uncomplaining sleep;

For he is gone, where all things wise and fair

Descend-oh, dream not that the amorous Deep

Will yet restore him to the vital air;

Death feeds on his mute voice, and laughs at our despair.

IV

Most musical of mourners, weep again!

Lament anew, Urania! He died,

Who was the Sire of an immortal strain,

Blind, old and lonely, when his country's pride,

The priest, the slave and the liberticide,

Trampled and mock'd with many a loathed rite

Of lust and blood; he went, unterrified,

Into the gulf of death; but his clear Sprite

Yet reigns o'er earth; the third among the sons of light.

V

Most musical of mourners, weep anew!

Not all to that bright station dar'd to climb;

And happier they their happiness who knew,

Whose tapers yet burn through that night of time

In which suns perish'd; others more sublime,

Struck by the envious wrath of man or god,

Have sunk, extinct in their refulgent prime;

And some yet live, treading the thorny road,

Which leads, through toil and hate, to Fame's serene abode.

VI

But now, thy youngest, dearest one, has perish'd,

The nursling of thy widowhood, who grew,

Like a pale flower by some sad maiden cherish'd,

And fed with true-love tears, instead of dew;

Most musical of mourners, weep anew!

Thy extreme hope, the loveliest and the last,

The bloom, whose petals nipp'd before they blew

Died on the promise of the fruit, is waste;

The broken lily lies-the storm is overpast.

VII

To that high Capital, where kingly Death

Keeps his pale court in beauty and decay,

He came; and bought, with price of purest breath,

A grave among the eternal.-Come away!

Haste, while the vault of blue Italian day

Is yet his fitting charnel-roof! while still

He lies, as if in dewy sleep he lay;

Awake him not! surely he takes his fill

Of deep and liquid rest, forgetful of all ill.

VIII

He will awake no more, oh, never more!

Within the twilight chamber spreads apace

The shadow of white Death, and at the door

Invisible Corruption waits to trace

His extreme way to her dim dwelling-place;

The eternal Hunger sits, but pity and awe

Soothe her pale rage, nor dares she to deface

So fair a prey, till darkness and the law

Of change shall o'er his sleep the mortal curtain draw.

IX

Oh, weep for Adonais! The quick Dreams,

The passion-winged Ministers of thought,

Who were his flocks, whom near the living streams

Of his young spirit he fed, and whom he taught

The love which was its music, wander not-

Wander no more, from kindling brain to brain,

But droop there, whence they sprung; and mourn their lot

Round the cold heart, where, after their sweet pain,

They ne'er will gather strength, or find a home again.

X

And one with trembling hands clasps his cold head,

And fans him with her moonlight wings, and cries,

"Our love, our hope, our sorrow, is not dead;

See, on the silken fringe of his faint eyes,

Like dew upon a sleeping flower, there lies

A tear some Dream has loosen'd from his brain."

Lost Angel of a ruin'd Paradise!

She knew not 'twas her own; as with no stain

She faded, like a cloud which had outwept its rain.

XI

One from a lucid urn of starry dew

Wash'd his light limbs as if embalming them;

Another clipp'd her profuse locks, and threw

The wreath upon him, like an anadem,

Which frozen tears instead of pearls begem;

Another in her wilful grief would break

Her bow and winged reeds, as if to stem

A greater loss with one which was more weak;

And dull the barbed fire against his frozen cheek.

XII

Another Splendour on his mouth alit,

That mouth, whence it was wont to draw the breath

Which gave it strength to pierce the guarded wit,

And pass into the panting heart beneath

With lightning and with music: the damp death

Quench'd its caress upon his icy lips;

And, as a dying meteor stains a wreath

Of moonlight vapour, which the cold night clips,

It flush'd through his pale limbs, and pass'd to its eclipse.

XIII

And others came . . Desires and Adorations,

Winged Persuasions and veil'd Destinies,

Splendours, and Glooms, and glimmering Incarnations

Of hopes and fears, and twilight Phantasies;

And Sorrow, with her family of Sighs,

And Pleasure, blind with tears, led by the gleam

Of her own dying smile instead of eyes,

Came in slow pomp; the moving pomp might seem

Like pageantry of mist on an autumnal stream.

XIV

All he had lov'd, and moulded into thought,

From shape, and hue, and odour, and sweet sound,

Lamented Adonais. Morning sought

Her eastern watch-tower, and her hair unbound,

Wet with the tears which should adorn the ground,

Dimm'd the aëreal eyes that kindle day;

Afar the melancholy thunder moan'd,

Pale Ocean in unquiet slumber lay,

And the wild Winds flew round, sobbing in their dismay.

XV

Lost Echo sits amid the voiceless mountains,

And feeds her grief with his remember'd lay,

And will no more reply to winds or fountains,

Or amorous birds perch'd on the young green spray,

Or herdsman's horn, or bell at closing day;

Since she can mimic not his lips, more dear

Than those for whose disdain she pin'd away

Into a shadow of all sounds: a drear

Murmur, between their songs, is all the woodmen hear.

XVI

Grief made the young Spring wild, and she threw down

Her kindling buds, as if she Autumn were,

Or they dead leaves; since her delight is flown,

For whom should she have wak'd the sullen year?

To Phoebus was not Hyacinth so dear

Nor to himself Narcissus, as to both

Thou, Adonais: wan they stand and sere

Amid the faint companions of their youth,

With dew all turn'd to tears; odour, to sighing ruth.

XVII

Thy spirit's sister, the lorn nightingale

Mourns not her mate with such melodious pain;

Not so the eagle, who like thee could scale

Heaven, and could nourish in the sun's domain

Her mighty youth with morning, doth complain,

Soaring and screaming round her empty nest,

As Albion wails for thee: the curse of Cain

Light on his head who pierc'd thy innocent breast,

And scar'd the angel soul that was its earthly guest!

XVIII

Ah, woe is me! Winter is come and gone,

But grief returns with the revolving year;

The airs and streams renew their joyous tone;

The ants, the bees, the swallows reappear;

Fresh leaves and flowers deck the dead Seasons' bier;

The amorous birds now pair in every brake,

And build their mossy homes in field and brere;

And the green lizard, and the golden snake,

Like unimprison'd flames, out of their trance awake.

XIX

Through wood and stream and field and hill and Ocean

A quickening life from the Earth's heart has burst

As it has ever done, with change and motion,

From the great morning of the world when first

God dawn'd on Chaos; in its stream immers'd,

The lamps of Heaven flash with a softer light;

All baser things pant with life's sacred thirst;

Diffuse themselves; and spend in love's delight,

The beauty and the joy of their renewed might.

XX

The leprous corpse, touch'd by this spirit tender,

Exhales itself in flowers of gentle breath;

Like incarnations of the stars, when splendour

Is chang'd to fragrance, they illumine death

And mock the merry worm that wakes beneath;

Nought we know, dies. Shall that alone which knows

Be as a sword consum'd before the sheath

By sightless lightning?-the intense atom glows

A moment, then is quench'd in a most cold repose.

XXI

Alas! that all we lov'd of him should be,

But for our grief, as if it had not been,

And grief itself be mortal! Woe is me!

Whence are we, and why are we? of what scene

The actors or spectators? Great and mean

Meet mass'd in death, who lends what life must borrow.

As long as skies are blue, and fields are green,

Evening must usher night, night urge the morrow,

Month follow month with woe, and year wake year to sorrow.

XXII

He will awake no more, oh, never more!

"Wake thou," cried Misery, "childless Mother, rise

Out of thy sleep, and slake, in thy heart's core,

A wound more fierce than his, with tears and sighs."

And all the Dreams that watch'd Urania's eyes,

And all the Echoes whom their sister's song

Had held in holy silence, cried: "Arise!"

Swift as a Thought by the snake Memory stung,

From her ambrosial rest the fading Splendour sprung.

XXIII

She rose like an autumnal Night, that springs

Out of the East, and follows wild and drear

The golden Day, which, on eternal wings,

Even as a ghost abandoning a bier,

Had left the Earth a corpse. Sorrow and fear

So struck, so rous'd, so rapt Urania;

So sadden'd round her like an atmosphere

Of stormy mist; so swept her on her way

Even to the mournful place where Adonais lay.

XXIV

Out of her secret Paradise she sped,

Through camps and cities rough with stone, and steel,

And human hearts, which to her aery tread

Yielding not, wounded the invisible

Palms of her tender feet where'er they fell:

And barbed tongues, and thoughts more sharp than they,

Rent the soft Form they never could repel,

Whose sacred blood, like the young tears of May,

Pav'd with eternal flowers that undeserving way.

XXV

In the death-chamber for a moment Death,

Sham'd by the presence of that living Might,

Blush'd to annihilation, and the breath

Revisited those lips, and Life's pale light

Flash'd through those limbs, so late her dear delight.

"Leave me not wild and drear and comfortless,

As silent lightning leaves the starless night!

Leave me not!" cried Urania: her distress

Rous'd Death: Death rose and smil'd, and met her vain caress.

XXVI

"Stay yet awhile! speak to me once again;

Kiss me, so long but as a kiss may live;

And in my heartless breast and burning brain

That word, that kiss, shall all thoughts else survive,

With food of saddest memory kept alive,

Now thou art dead, as if it were a part

Of thee, my Adonais! I would give

All that I am to be as thou now art!

But I am chain'd to Time, and cannot thence depart!

XXVII

"O gentle child, beautiful as thou wert,

Why didst thou leave the trodden paths of men

Too soon, and with weak hands though mighty heart

Dare the unpastur'd dragon in his den?

Defenceless as thou wert, oh, where was then

Wisdom the mirror'd shield, or scorn the spear?

Or hadst thou waited the full cycle, when

Thy spirit should have fill'd its crescent sphere,

The monsters of life's waste had fled from thee like deer.

XXVIII

"The herded wolves, bold only to pursue;

The obscene ravens, clamorous o'er the dead;

The vultures to the conqueror's banner true

Who feed where Desolation first has fed,

And whose wings rain contagion; how they fled,

When, like Apollo, from his golden bow

The Pythian of the age one arrow sped

And smil'd! The spoilers tempt no second blow,

They fawn on the proud feet that spurn them lying low.

XXIX

"The sun comes forth, and many reptiles spawn;

He sets, and each ephemeral insect then

Is gather'd into death without a dawn,

And the immortal stars awake again;

So is it in the world of living men:

A godlike mind soars forth, in its delight

Making earth bare and veiling heaven, and when

It sinks, the swarms that dimm'd or shar'd its light

Leave to its kindred lamps the spirit's awful night."

XXX

Thus ceas'd she: and the mountain shepherds came,

Their garlands sere, their magic mantles rent;

The Pilgrim of Eternity (age 33), whose fame

Over his living head like Heaven is bent,

An early but enduring monument,

Came, veiling all the lightnings of his song

In sorrow; from her wilds Ierne sent

The sweetest lyrist of her saddest wrong,

And Love taught Grief to fall like music from his tongue.

XXXI

Midst others of less note, came one frail Form,

A phantom among men; companionless

As the last cloud of an expiring storm

Whose thunder is its knell; he, as I guess,

Had gaz'd on Nature's naked loveliness,

Actaeon-like, and now he fled astray

With feeble steps o'er the world's wilderness,

And his own thoughts, along that rugged way,

Pursu'd, like raging hounds, their father and their prey.

XXXII

A pardlike Spirit beautiful and swift-

A Love in desolation mask'd-a Power

Girt round with weakness-it can scarce uplift

The weight of the superincumbent hour;

It is a dying lamp, a falling shower,

A breaking billow; even whilst we speak

Is it not broken? On the withering flower

The killing sun smiles brightly: on a cheek

The life can burn in blood, even while the heart may break.

XXXIII

His head was bound with pansies overblown,

And faded violets, white, and pied, and blue;

And a light spear topp'd with a cypress cone,

Round whose rude shaft dark ivy-tresses grew

Yet dripping with the forest's noonday dew,

Vibrated, as the ever-beating heart

Shook the weak hand that grasp'd it; of that crew

He came the last, neglected and apart;

A herd-abandon'd deer struck by the hunter's dart.

XXXIV

All stood aloof, and at his partial moan

Smil'd through their tears; well knew that gentle band

Who in another's fate now wept his own,

As in the accents of an unknown land

He sung new sorrow; sad Urania scann'd

The Stranger's mien, and murmur'd: "Who art thou?"

He answer'd not, but with a sudden hand

Made bare his branded and ensanguin'd brow,

Which was like Cain's or Christ's-oh! that it should be so!

XXXV

What softer voice is hush'd over the dead?

Athwart what brow is that dark mantle thrown?

What form leans sadly o'er the white death-bed,

In mockery of monumental stone,

The heavy heart heaving without a moan?

If it be He, who, gentlest of the wise,

Taught, sooth'd, lov'd, honour'd the departed one,

Let me not vex, with inharmonious sighs,

The silence of that heart's accepted sacrifice.

XXXVI

Our Adonais has drunk poison-oh!

What deaf and viperous murderer could crown

Life's early cup with such a draught of woe?

The nameless worm would now itself disown:

It felt, yet could escape, the magic tone

Whose prelude held all envy, hate and wrong,

But what was howling in one breast alone,

Silent with expectation of the song,

Whose master's hand is cold, whose silver lyre unstrung.

XXXVII

Live thou, whose infamy is not thy fame!

Live! fear no heavier chastisement from me,

Thou noteless blot on a remember'd name!

But be thyself, and know thyself to be!

And ever at thy season be thou free

To spill the venom when thy fangs o'erflow;

Remorse and Self-contempt shall cling to thee;

Hot Shame shall burn upon thy secret brow,

And like a beaten hound tremble thou shalt-as now.

XXXVIII

Nor let us weep that our delight is fled

Far from these carrion kites that scream below;

He wakes or sleeps with the enduring dead;

Thou canst not soar where he is sitting now.

Dust to the dust! but the pure spirit shall flow

Back to the burning fountain whence it came,

A portion of the Eternal, which must glow

Through time and change, unquenchably the same,

Whilst thy cold embers choke the sordid hearth of shame.

XXXIX

Peace, peace! he is not dead, he doth not sleep,

He hath awaken'd from the dream of life;

'Tis we, who lost in stormy visions, keep

With phantoms an unprofitable strife,

And in mad trance, strike with our spirit's knife

Invulnerable nothings. We decay

Like corpses in a charnel; fear and grief

Convulse us and consume us day by day,

And cold hopes swarm like worms within our living clay.

XL

He has outsoar'd the shadow of our night;

Envy and calumny and hate and pain,

And that unrest which men miscall delight,

Can touch him not and torture not again;

From the contagion of the world's slow stain

He is secure, and now can never mourn

A heart grown cold, a head grown gray in vain;

Nor, when the spirit's self has ceas'd to burn,

With sparkless ashes load an unlamented urn.

XLI

He lives, he wakes-'tis Death is dead, not he;

Mourn not for Adonais. Thou young Dawn,

Turn all thy dew to splendour, for from thee

The spirit thou lamentest is not gone;

Ye caverns and ye forests, cease to moan!

Cease, ye faint flowers and fountains, and thou Air,

Which like a mourning veil thy scarf hadst thrown

O'er the abandon'd Earth, now leave it bare

Even to the joyous stars which smile on its despair!

XLII

He is made one with Nature: there is heard

His voice in all her music, from the moan

Of thunder, to the song of night's sweet bird;

He is a presence to be felt and known

In darkness and in light, from herb and stone,

Spreading itself where'er that Power may move

Which has withdrawn his being to its own;

Which wields the world with never-wearied love,

Sustains it from beneath, and kindles it above.

XLIII

He is a portion of the loveliness

Which once he made more lovely: he doth bear

His part, while the one Spirit's plastic stress

Sweeps through the dull dense world, compelling there

All new successions to the forms they wear;

Torturing th' unwilling dross that checks its flight

To its own likeness, as each mass may bear;

And bursting in its beauty and its might

From trees and beasts and men into the Heaven's light.

XLIV

The splendours of the firmament of time

May be eclips'd, but are extinguish'd not;

Like stars to their appointed height they climb,

And death is a low mist which cannot blot

The brightness it may veil. When lofty thought

Lifts a young heart above its mortal lair,

And love and life contend in it for what

Shall be its earthly doom, the dead live there

And move like winds of light on dark and stormy air.

XLV

The inheritors of unfulfill'd renown

Rose from their thrones, built beyond mortal thought,

Far in the Unapparent. Chatterton

Rose pale, his solemn agony had not

Yet faded from him; Sidney, as he fought

And as he fell and as he liv'd and lov'd

Sublimely mild, a Spirit without spot,

Arose; and Lucan, by his death approv'd:

Oblivion as they rose shrank like a thing reprov'd.

XLVI

And many more, whose names on Earth are dark,

But whose transmitted effluence cannot die

So long as fire outlives the parent spark,

Rose, rob'd in dazzling immortality.

"Thou art become as one of us," they cry,

"It was for thee yon kingless sphere has long

Swung blind in unascended majesty,

Silent alone amid a Heaven of Song.

Assume thy winged throne, thou Vesper of our throng!"

XLVII

Who mourns for Adonais? Oh, come forth,

Fond wretch! and know thyself and him aright.

Clasp with thy panting soul the pendulous Earth;

As from a centre, dart thy spirit's light

Beyond all worlds, until its spacious might

Satiate the void circumference: then shrink

Even to a point within our day and night;

And keep thy heart light lest it make thee sink

When hope has kindled hope, and lur'd thee to the brink.

XLVIII

Or go to Rome, which is the sepulchre,

Oh, not of him, but of our joy: 'tis nought

That ages, empires and religions there

Lie buried in the ravage they have wrought;

For such as he can lend-they borrow not

Glory from those who made the world their prey;

And he is gather'd to the kings of thought

Who wag'd contention with their time's decay,

And of the past are all that cannot pass away.

XLIX

Go thou to Rome-at once the Paradise,

The grave, the city, and the wilderness;

And where its wrecks like shatter'd mountains rise,

And flowering weeds, and fragrant copses dress

The bones of Desolation's nakedness

Pass, till the spirit of the spot shall lead

Thy footsteps to a slope of green access

Where, like an infant's smile, over the dead

A light of laughing flowers along the grass is spread;

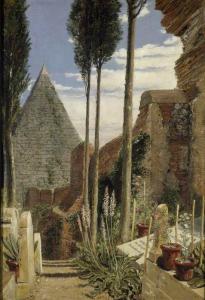

L

And gray walls moulder round, on which dull Time

Feeds, like slow fire upon a hoary brand;

And one keen pyramid with wedge sublime,

Pavilioning the dust of him who plann'd

This refuge for his memory, doth stand

Like flame transform'd to marble; and beneath,

A field is spread, on which a newer band

Have pitch'd in Heaven's smile their camp of death,

Welcoming him we lose with scarce extinguish'd breath.

LI

Here pause: these graves are all too young as yet

To have outgrown the sorrow which consign'd

Its charge to each; and if the seal is set,

Here, on one fountain of a mourning mind,

Break it not thou! too surely shalt thou find

Thine own well full, if thou returnest home,

Of tears and gall. From the world's bitter wind

Seek shelter in the shadow of the tomb.

What Adonais is, why fear we to become?

LII

The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven's light forever shines, Earth's shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-colour'd glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.-Die,

If thou wouldst be with that which thou dost seek!

Follow where all is fled!-Rome's azure sky,

Flowers, ruins, statues, music, words, are weak

The glory they transfuse with fitting truth to speak.

LIII

Why linger, why turn back, why shrink, my Heart?

Thy hopes are gone before: from all things here

They have departed; thou shouldst now depart!

A light is pass'd from the revolving year,

And man, and woman; and what still is dear

Attracts to crush, repels to make thee wither.

The soft sky smiles, the low wind whispers near:

'Tis Adonais calls! oh, hasten thither,

No more let Life divide what Death can join together.

LIV

That Light whose smile kindles the Universe,

That Beauty in which all things work and move,

That Benediction which the eclipsing Curse

Of birth can quench not, that sustaining Love

Which through the web of being blindly wove

By man and beast and earth and air and sea,

Burns bright or dim, as each are mirrors of

The fire for which all thirst; now beams on me,

Consuming the last clouds of cold mortality.

LV

The breath whose might I have invok'd in song

Descends on me; my spirit's bark is driven,

Far from the shore, far from the trembling throng

Whose sails were never to the tempest given;

The massy earth and sphered skies are riven!

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar;

Whilst, burning through the inmost veil of Heaven,

The soul of Adonais, like a star,

Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. The last residence of Shelley was the Casa Magni, a bare and exposed dwelling on the Gulf of Spezia. He and his wife, with the Williamses, went there at the end of April 1822 to spend the summer, which proved an arid and scorching one.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Shelley and Williams, both of them insatiably fond of boating, had a small schooner named the "Don Juan" (or more properly the "Ariel"), built at Genoa after a design which Williams had procured from a naval friend, but the reverse of safe. They received her on the 12th of May, found her rapid and alert, and on the 1st of July started in her to Leghorn, to meet Leigh Hunt, whose arrival in Italy had just been notified.

On 08 Jul 1822 Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned. He was returning on the Don Juan with Edward Williams from a meeting at Livorno with Leigh Hunt and Byron to make arrangements for a new journal, The Liberal. The boat was sunk is a storm. Shelley's badly decomposed body washed ashore at Viareggio ten days later and was identified by Trelawny from the clothing and a copy of Keats's Lamia in a jacket pocket. On 16 Aug 1822 his body was cremated on a beach near Viareggio and the ashes were buried in the Protestant Cemetery of Rome. The cremation was attended by George "Lord Byron" 6th Baron Byron (age 34). His wife [his wife] Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 24) did not attend.

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. After doing his best to set things going comfortably between Byron and Hunt, Shelley returned on board with Williams on the 8th of July. It was a day of dark, louring, stifling heat. Trelawny took leave of his two friends, and about half-past six in the evening found himself startled from a doze by a frightful turmoil of storm. The "Don Juan" had by this time made Via Reggio; she was not to be seen, though other vessels which had sailed about the same time were still discernible. Shelley, Williams, and their only companion, a sailor-boy, perished in the squall. The exact nature of the catastrophe was from the first regarded as somewhat disputable. The condition of the "Don Juan" when recovered did not favour any assumption that she had capsized in a heavy sea - rather that she had been run down by some other vessel, a felucca or fishing-smack. In the absence of any counter evidence this would be supposed to have occurred by accident; but a rumour, not strictly verified and certainly not refuted, exists that an aged Italian seaman on his deathbed confessed that he had been one of the crew of the fatal felucca, and that the collision was intentional, as the men had plotted to steal a sum of money supposed to be on the "Don Juan," in charge of Lord Byron. In fact there was a moderate sum there, but Byron had neither embarked nor intended to embark. This may perhaps be the true account of the tragedy; at any rate Trelawny, the best possible authority on the subject, accepted it as true. He it was who laboriously tracked out the shore washed corpses of Williams and Shelley, and who undertook the burning of them, after the ancient Greek fashion, on the shore near Via Reggio, on the 15th and 16th of August. The great poet's ashes were then collected, and buried in the new Protestant cemetery in Rome. He was, at the date of his untimely death, within a month of completing the thirtieth year of his age – a surprising example of rich poetic achievement for so young a man.

After 08 Jul 1822. Monument to Percy Bysshe Shelley in Christchurch Priory [Map]. Sculpted by Henry Weekes (age 15). The monument possibly contains Shelley's heart, possibly liver, which resisted cremation and was retrieved by Edward Trelawny who was present at the cremation.

The monument verse forty of fifty-five of Shelley's Adonais: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, Author of Endymion, Hyperion, etc:

He has out-soared the shadow of our night;.

Envy and calumny, and hate and pain,.

And that unrest which men miscall delight,.

Can touch him not and torture not again;.

From the contagion of the world's slow stain.

He is secure, and now can never mourn.

A heart grown cold, a head grown gray in vain;.

Nor when the spirit's self has ceased to burn,.

With sparkless ashes load an unlamented urn.

1873. William Bell Scott (age 62). "Shelley's Grave".

1873. William Bell Scott (age 62). "Shelley's Grave".

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. Shelley, Percy Bysshe by William Michael Rossetti (age 81).

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. If we except Goethe (and leave out of count any living writers, whose ultimate value cannot at present be assessed), we must consider Shelley to be the supreme poet of the new era which, beginning with the French Revolution, remains continuous into our own day. Victor Hugo comes nearest to him in poetic stature, and might for certain reasons be even preferred to him; Byron and Wordsworth also have their numerous champions—not to speak of Tennyson or Browning. The grounds, however, on which Shelley may be set highest of all are mainly three. He excels all his competitors in ideality, he excels them in music, and he excels them in importance. By importance we here mean the direct import of the work performed, its controlling power over the reader's thought and feeling, the contagious fire of its white-hot intellectual passion, and the long reverberation of its appeal. Shelley is emphatically the poet of the future. In his own dayan alien in the world of mind and invention, and in our day but partially a denizen of it, he appears destined to become, in the long vista of years, an informing presence in the innermost shrine of human thought. Shelley appeared at the time when the sublime frenzies of the French revolutionary movement had exhausted the elasticity of men's thought—at least in England—and had left them flaccid and stolid; but that movement prepared another in which revolution was to assume the milder guise of reform, conquering and to conquer. Shelley was its prophet. As an iconoclast and an idealist he took the only position in which a poet could advantageously work as a reformer. To outrage his contemporaries was the condition of leading his successors to triumph and of personally triumphing in their victories. Shelley had the temper of an innovator and a martyr; and in an intellect wondrously poetical he united speculative keenness and humanitarian zeal in a degree for which we might vainly seek his precursor. We have already named ideality as one of his leading excellences. This Shelleian quality combines, as its constituents, sublimity, beauty and the abstract passion for good. It should be acknowledged that, while this great quality forms the chief and most admirable factor in Shelley's poetry, the defects which go along with it mar his work too often—producing at times vagueness, unreality and a pomp of glittering indistinctness, in which excess of sentiment welters amid excess of words. This blemish affects the long poems much more than the pure lyrics; in the latter the rapture, the music and the emotion are in exquisite balance, and the work has often as much of delicate simplicity as of fragile and flower-like perfection.

Great x 4 Grandfather: John Shelley

Great x 3 Grandfather: Timothy Shelley

Great x 2 Grandfather: John Shelley

Great x 1 Grandfather: Timothy Shelley

GrandFather: Bysshe Shelley 1st Baronet

Father: Timothy Shelley 2nd Baronet

Great x 1 Grandfather: Reverend Theobald Michell of Horsham

GrandMother: Mary Catherine Michell

GrandFather: Charles Pilfold of Effingham, Surrey

Mother: Elizabeth Pilfold