Biography of William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings 1431-1483

Paternal Family Tree: Hastings

Maternal Family Tree: Elizabeth Louches Baroness Camoys

1461 Battle of Mortimer's Cross

1461 Proclamation of Edward IV as King

1461 Edward IV Rewards his Followers

1462 Creation of Garter Knights

1467 Tournament Bastard of Burgundy

1470 Welles' Rebellion and Battle of Losecoat Field aka Empingham

1471 King Edward lands at Ravenspur

Before 1423 [his father] Leonard Hastings (age 27) and [his mother] Alice Camoys were married.

Around 1431 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings was born to Leonard Hastings (age 35) and Alice Camoys.

In or before 1448 Henry Fitzhugh 5th Baron Fitzhugh (age 19) and [his future sister-in-law] Alice Neville Baroness Fitzhugh (age 17) were married. She by marriage Baroness Fitzhugh. She the daughter of Richard Neville Earl Salisbury (age 47) and Alice Montagu 5th Countess of Salisbury (age 40). They were third cousin once removed. She a great x 2 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

In 1451 Thomas Stanley 1st Earl of Derby (age 16) and [his future sister-in-law] Eleanor Neville Baroness Stanley (age 4) were married in the Chapel at Middleham Castle [Map]. She the daughter of Richard Neville Earl Salisbury (age 51) and Alice Montagu 5th Countess of Salisbury (age 44). They were third cousins. He a great x 4 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England. She a great x 2 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

In 1455 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 24) was appointed High Sheriff of Leicestershire and High Sheriff of Warwickshire.

On 20 Oct 1455 [his father] Leonard Hastings (age 59) died at Kirkby, Leicestershire.

In 1458 William Bonville 6th Baron Harington (age 16) and [his future wife] Katherine Neville Baroness Bonville and Hastings (age 16) were married. She the daughter of Richard Neville Earl Salisbury (age 58) and Alice Montagu 5th Countess of Salisbury (age 51). She a great x 2 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

In 1461 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 30) was appointed Master of the Mint.

In 1461 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 30) was appointed Lord Chamberlain.

On 02 Feb 1461 at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross at Mortimer's Cross, Herefordshire [Map] the future King Edward IV of England (age 18) commanded the Yorkist forces including William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 30), John Wenlock 1st Baron Wenlock (age 61), John Tuchet 6th Baron Audley, 3rd Baron Tuchet (age 35), John Savage (age 17) and Roger Vaughan (age 51).

In the Lancastrian army Owen Tudor (age 61) (captured by Roger Vaughan (age 51)) and his son Jasper Tudor 1st Duke Bedford (age 29) fought as well as James Butler 1st Earl Wiltshire 5th Earl Ormonde (age 40) and Henry Roos. Gruffydd ap Nicholas Deheubarth (age 68) were killed. Watkin Vaughan (age 66) and Henry Wogan (age 59) were killed.

Monument to the Battle of Mortimer's Cross at Mortimer's Cross, Herefordshire [Map]. Note the mistake - Edward IV described as Edward Mortimer. The monument was erected by subscription in 1799.

Gruffydd ap Nicholas Deheubarth: In 1393 he was born to Nicolas ap Philip Deheubarth and Jonet Unknown at Sheffield.

Watkin Vaughan:

Around 1395 he was born to Roger Vaughan of Bredwardine and Gwladys ferch Dafydd Gam "Star of Abergavenny" Brecon.

Around 1435 Watkin Vaughan and Elinor Wogan were married. The date based on his age being around twenty. The difference in their ages was 29 years.

Henry Wogan: In 1402 he was born to John Wogan at Wiston.

On 04 Mar 1461 King Edward IV of England (age 18) declared himself King of England. William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 30) was present.

On 29 Mar 1461 the Battle of Towton was a decisive victory for King Edward IV of England (age 18) bringing to an end the first war of the Wars of the Roses. Said to be the bloodiest battle on English soil 28000 were killed mainly during the rout that followed the battle.

The Yorkist army was commanded by King Edward IV of England (age 18) with John Mowbray 3rd Duke of Norfolk (age 45), William Neville 1st Earl Kent (age 56), William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 30) (knighted), Walter Blount 1st Baron Mountjoy (age 45), Henry Bourchier 2nd Count Eu 1st Earl Essex (age 57), John Scrope 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton (age 23) and John Wenlock 1st Baron Wenlock (age 61).

The Lancastrian army suffered significant casualties including Richard Percy (age 35), Ralph Bigod Lord Morley (age 50), John Bigod (age 28), Robert Cromwell (age 71), Ralph Eure (age 49), John Neville 1st Baron Neville of Raby (age 51), John Beaumont (age 33), Thomas Dethick (age 61), Everard Simon Digby, William Plumpton (age 25) and William Welles (age 51) who were killed.

Henry Percy 3rd Earl of Northumberland (age 39) was killed. His son Henry Percy 4th Earl of Northumberland (age 12) succeeded 4th Earl of Northumberland, 7th Baron Percy of Alnwick, 15th Baron Percy of Topcliffe. Maud Herbert Countess Northumberland (age 3) by marriage Countess of Northumberland.

Ralph Dacre 1st Baron Dacre Gilsland (age 49) was killed. He was buried at the nearby Saxton church where his chest tombs is extant. Baron Dacre Gilsland extinct.

Lionel Welles 6th Baron Welles (age 55) was killed. His son Richard Welles 7th Baron Willoughby 7th Baron Welles (age 33) succeeded 7th Baron Welles.

The Lancastrian army was commanded by Henry Beaufort 2nd or 3rd Duke Somerset (age 25), Henry Holland 3rd Duke Exeter (age 30), Henry Percy 3rd Earl of Northumberland (age 39) and Andrew Trollope.

Henry Holland 3rd Duke Exeter (age 30) was attainted after the battle; Duke Exeter, Earl Huntingdon forfeit.

Those who fought for the Lancaster included William Tailboys 7th Baron Kyme (age 46), John Dudley 1st Baron Dudley (age 60), William Norreys (age 20), Thomas Grey 1st Baron Grey of Richemont (age 43), Robert Hungerford 3rd Baron Hungerford 1st Baron Moleyns (age 30), John Talbot 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury (age 12), Richard Welles 7th Baron Willoughby 7th Baron Welles (age 33), Richard Woodville 1st Earl Rivers (age 56), James Butler 1st Earl Wiltshire 5th Earl Ormonde (age 40), John Butler 6th Earl Ormonde (age 39), William Beaumont 2nd Viscount Beaumont (age 22), Henry Roos and Thomas Tresham (age 41). Cardinal John Morton (age 41) were captured.

Paston Letters Volume 2 450. 04 Apr 1461. William Paston and John Playters to John Paston (age 39).

To my maister, John Paston, in hast,

Please you to knowe and wete of suche tydyngs as my Lady of York hath by a lettre of credens, under the signe manuel of oure Soverayn Lord King Edward, whiche lettre cam un to oure sayd Lady this same day, Esterne Evyn, at xj. clok, and was sene and red by me, William Paston.

Fyrst, oure Soverayn Lord (age 18) hath wonne the feld, and uppon the Munday next after Palmesunday, he was resseved in to York with gret solempnyte and processyons. And the Mair the Yorkist cause and Comons of the said cite mad ther menys to have grace be [his future brother-in-law] Lord Montagu (age 30) and Lord Barenars (age 45), whiche be for the Kyngs coming in to the said cite desyred hym of grace for the said cite, whiche graunted hem grace. On the Kyngs parte is slayn Lord Fitz Water (deceased), and Lord Scrop (age 23) sore hurt; John Stafford, Horne of Kent ben ded; and Umfrey Stafford, William Hastyngs (age 30) mad knyghts with other; Blont is knygth, &c.

Un the contrary part is ded Lord Clyfford (deceased), Lord Nevyle (deceased), Lord Welles (deceased), Lord Wyllouby, Antony Lord Scales, Lord Harry, and be supposyng the Erle of Northumberland, Andrew Trollop, with many other gentyll and comons to the nomber of xx.ml. (20000).

Item, Kyng Harry, the Qwen, the Prince, Duke of Somerset, Duke of Exeter, Lord Roos, be fledde in to Scotteland, and they be chased and folwed, &c. We send no er un to you be cause we had non certynges tyl now; for un to this day London was as sory cite as myght. And because Spordauns had no certeyn tydyngs, we thought ye schuld take them a worthe tyl more certayn.

Item, Thorp Waterfeld is yeldyn, as Spordauns can telle you. And Jesu spede you. We pray you that this tydyngs my moder may knowe.

Be your Broder,

W. PASTON.

T. PLAYTERS.

Comes Northumbriæ (deceased).

Comes Devon (deceased).

Dominus de Beamunde.

Dominus de Clifford (deceased).

Dominus de Nevyll (deceased).

Dominus de Dacre (deceased).

Dominus Henricus de Bokyngham.

Dominus de Well[es] (deceased).

Dominus de Scales Antony Revers.

Dominus de Wellugby.

Dominus de Malley Radulfus Bigot Miles.

Millites.

Sir Rauff Gray.

Sir Ric. Jeney.

Sir Harry Bekingham.

Sir Andrew Trollop.

With xxviij.ml. (28000) nomberd by Harralds.

Warkworth's Chronicle 1461. 27 Jun 1461.... at the coronacyone1 of the forseyde Edwarde, he create and made dukes his two brythir, the eldere George (age 11) Duke of Clarence, and his yongere brothir Richard (age 8) Duke of Gloucetre; and the [his future brother-in-law] Lord Montagu (age 30)2, the Erle of Warwykes (age 32) brothere, the Erle of Northumberlonde; and one William Stafford squiere, Lord Stafforde of Southwyke; and Sere Herbard (age 38), Lorde Herbard, and aftere Lorde Erle of Penbroke3; and so the seide Lorde Stafforde (age 22) was made Erle of Devynschire4; the Lorde Gray Ryffyne (age 44), Erle of Kent6; the Lorde Bourchyer (age 57), Erle of Essex; the Lorde Jhon of Bokyngham (age 33), the Erle of Wyltschyre5; Sere Thomas [Walter] Blount (age 45), knyghte, Lord Mont[joy]; Sere Jhon Hawarde, Lorde Hawarde (age 36)8; William Hastynges (age 30) he made Lorde Hastynges and grete Chamberlayne; and the Lorde Ryvers; Denham squyere, Lorde Dynham; and worthy as is afore schewed; and othere of gentylmen and yomenne he made knyghtes and squyres, as thei hade desserved.

Note 1. At the coronacyone. King Edward was crowned in Westminster Abbey, on the 29th of June 1461. Warkworth's first passage is both imperfect and incorrect, and would form a very bad specimen of the value of the subsequent portions of his narrative; yet we find it transferred to the Chronicle of Stowe. It must, however, be regarded rather as a memorandum of the various creations to the peerage made during Edward's reign, than as a part of the chronicle. Not even the third peerage mentioned, the Earldom of Northumberland, was conferred at the Coronation, but by patent dated 27 May 1464: and the only two Earldoms bestowed in Edward's first year (and probably at the Coronation) were, the Earldom of Essex, conferred on Henry Viscount Bourchier, Earl of Eu in Normandy, who had married the King's aunt, the Princess Isabel of York; and the Earldom of Kent, conferred on William Neville, Lord Fauconberg, one of King Edward's generals at Towton. The former creation is mentioned by Warkworth lower down in his list; the latter is omitted altogether. - J.G.N.

Note 2. The Lord Montagu. And then Kyng Edward, concidering the greate feate doon by the said Lord Montagu, made hym Erle of Northumberlond; and in July next folowyng th'Erle of Warwyk, with th'ayde of the said Erle of Northumberland, gate agayn the castell of Bamborugh, wheryn was taken Sir Raaf Gray (age 29), which said Ser Raaf (age 29) was after behedid and quartred at York. Also, in this yere, the first day of May, the Kyng wedded Dame Elizabeth Gray (age 24), late wif unto the lord Gray of Groby, and doughter to the Lord Ryvers." - The London Chronicle, MS. Cotton. Vitell. A. xvi. fol. 126, ro. The MS. of the London Chronicle, from which Sir Harris Nicolas printed his edition, does not contain this passage. It is almost unnecessary to remark the chronological incorrectness of the above, but it serves to show how carelessly these slight Chronicles were compiled. Cf. MS. Add. Mus. Brit. 6113, fol. 192, rº. and MS. Cotton. Otho, B. XIV. fol. 221, ro.

Note 3. Lord Erle of Pembroke. William Lord Herbert of Chepstow (age 38), the first of the long line of Herbert Earls of Pembroke, was so created the 27th May 1468. His decapitation by the Duke of Clarence at Northampton in 1469, is noticed by Warkworth in p. 7.-J.G.N.

Note 4. Erle of Devynschire. Humphery Stafford (age 22), created Baron Stafford of Southwick by patent 24th April 1464, was advanced to the Earldom of Devon 7th May 1469; but beheaded by the commons at Bridgwater before the close of the same year, as related by Warkworth, ubi supra. - J.G.N.

Note 5. Erle of Wyltschyre. John Stafford (age 33), created Earl of Wiltshire, 5th Jan. 1470; he died in 1473.—J.G.N.

Note 6. "The Lorde Gray Ryffyne, Erle of Kent". The Earl of Kent, of the family of Neville, died without male issue, a few months after his elevation to that dignity; and it was conferred on the 30th May 1465, on Edmund Lord Grey de Ruthyn (age 44), on occasion of the Queen's coronation. He was cousin-german to Sir John Grey, of Groby, the Queen's first husband. On the same occasion the Queen's son Sir Thomas Grey (age 6) was created Marquess of Dorset; her father Richard Wydevile (age 56) lord Ryvers was advanced to the dignity of Earl Ryvers; and her brother Anthony (age 21) married to the heiress of Scales, in whose right he was summoned to Parliament as a Baron. - J.G.N.

Note 7. Sere Thomas Blount (age 45). This should be Walter, created Lord Montjoy 20th June 1465; he died in 1474.-J.G.N.

Note 8. Sere Jhon Hawarde, Lord Hawarde. John Howard 1st Duke of Norfolk (age 36). This peerage dates its origin, by writ of summons to Parliament, during the short restoration of Henry VI. in 1470, a circumstance more remarkable as "evidence exists that he did not attach himself to the interest of that Prince, being constitued by Edward, in the same year, commander of his fleet." See Sir Harris Nicolas's memoir of this distinguished person (afterwards the first Duke of Norfolk) in Cartwright's History of the Rape of Bramber, p. 189.-J.G.N.

On 26 Jul 1461 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 30) was created 1st Baron Hastings for supporting King Edward IV of England (age 19) in his claim to the throne.

Robert Ogle 1st Baron Ogle (age 55) was created 1st Baron Ogle by King Edward IV of England (age 19) for having been the principal Northumbrian gentleman to support the Yorkist cause.

In 1462 King Edward IV of England (age 19) appointed new Garter Knights:

187th John "Butcher of England" Tiptoft 1st Earl of Worcester (age 34).

188th William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 31).

189th [his future brother-in-law] John Neville 1st Marquess Montagu (age 31).

190th William "Black William" Herbert 1st Earl Pembroke (age 39).

191st John Astley.

Before 06 Feb 1462 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 31) and Katherine Neville Baroness Bonville and Hastings (age 20) were married. She by marriage Baroness Hastings. She the daughter of Richard Neville Earl Salisbury and Alice Montagu 5th Countess of Salisbury (age 55). She a great x 2 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

Calendars. 23 Jun 1463. Inspeximus and confirmation to the mayor, bailiffs and burgesses of Clyfton, Dertmuth and Hardenesse of (1) letters patent dated 14 December, 2 Richard II. inspecting and confirming a charter dated at the Tower of London, 14 April, 15 Edward III. [Charter Roll, 15 Edward III. No. 18,] and (2) a charter dated at Westminster, 5 November, 17 Richard II. [Charter Noll, 15-17 Richard II. No. 10]; and grant that the adjoining township of Southtouudertemouth shall henceforth be annexed to the said borough of Cliftondertemouth Hardenasse, in consideration of the fact that the burgesses keep watches against invaders on the confines of the township and beyond at a place called 'Galions Boure' but the inhabitants of the township contribute nothing because they do not enjoy the liberties of the borough. Th« mayor and bailiffs shall have return of writs and execu- tion thereof within the said township and the liberty of the borough, saving always the right of the lord of the fee of the township, and all pleas real and personal and attachments and fines and amercements, and also view of frauk-pledge and all that peitains to it. And they may acquire, in mortmain, after inquisition, lands, tenements, rents and other possessions, not held in chief, to the value of 201. yearly. Witnesses: Th. archbishop of Canterbury (age 45), W. archbishop of York (age 75), [his brother-in-law] G. Bishop of Exeter (age 31), the chancellor, J. Bishop of Carlisle, the king's brothers George, duke of Clarence (age 13), and Richard, duke of Gloucester (age 10), the king's kinsmen [his brother-in-law] Richard, Earl of Warwick (age 34), and John, Earl of Worcester (age 36), treasurer of England, Robert Styllyngton (age 43), king's clerk, keeper of the privy seal, and William Hastynges of Hastynges (age 32), the king's chamberlain, and John Wenlok of Wenlok (age 63), knights.

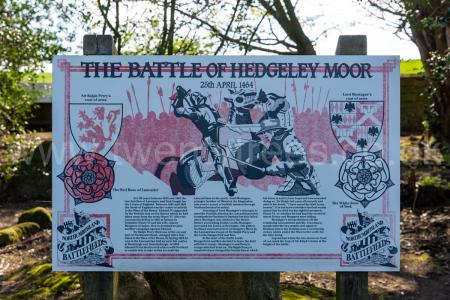

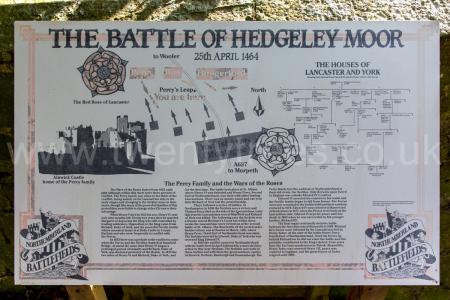

On 25 Apr 1464 a Yorkist army commanded by [his brother-in-law] John Neville 1st Marquess Montagu (age 33) defeated a Lancastrian army commanded by Henry Beaufort 2nd or 3rd Duke Somerset (age 28) at Hedgeley Moor [Map] during the Battle of Hedgeley Moor.

Of the Lancastrians ...

Thomas Ros 9th Baron Ros Helmsley (age 36) was killed. His son Edmund Ros 10th Baron Ros Helmsley (age 9) succeeded 10th Baron Ros Helmsley. Thomas' lands however, including Belvoir Castle [Map] was given by King Edward IV of England (age 21) to William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 33).

Ralph Percy (age 39) was killed.

Edmund Ros 10th Baron Ros Helmsley: Around 1455 he was born to Thomas Ros 9th Baron Ros Helmsley and Philippa Tiptoft Baroness Ros Helmsley. On 23 Oct 1508 Edmund Ros 10th Baron Ros Helmsley died. Baron Ros Helmsley abeyant between his daughters.

On 18 May 1464 Robert Hungerford 3rd Baron Hungerford 1st Baron Moleyns (age 33) was executed at Newcastle upon Tyne [Map] having been captured at the Battle of Hexham. He was buried at the Hungerford Chapel at Salisbury Cathedral [Map]. His daughter [his future daughter-in-law] Mary Hungerford Baroness Hastings, 4th Baroness Hungerford, 5th Baroness Botreaux and 2nd Baroness Moleyns became the ward of William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 33) whose son [his son] Edward Hastings 2nd Baron Hastings Baron Botreaux, Hungerford and Moleyns she subsequently married.

On 26 Nov 1466 [his son] Edward Hastings 2nd Baron Hastings Baron Botreaux, Hungerford and Moleyns was born to William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 35) and [his wife] Katherine Neville Baroness Bonville and Hastings (age 24) at Kirkby Muxloe Castle [Map]. He a great x 3 grandson of King Edward III of England.

On 29 May 1467 King Edward IV of England (age 25) and Antoine "Bastard of Burgundy" (age 46) met at Chelsea. William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 36), Henry Bourchier 2nd Count Eu 1st Earl Essex (age 63), Henry Stafford 2nd Duke of Buckingham (age 12), Anthony Woodville 2nd Earl Rivers (age 27), James Douglas 9th Earl Douglas 3rd Earl Avondale (age 41) and Thomas Montgomery accompanied Edward.

On 19 Mar 1470 Robert Welles 8th Baron Willoughby 8th Baron Welles was beheaded at Doncaster [Map]. He was buried at Whitefriars Doncaster [Map]. His sister Joan Welles 9th Baroness Willoughby Eresby succeeded 9th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby. [his brother] Richard Hastings Baron Willoughby (age 37) by marriage Baron Willoughby de Eresby. He, Hastings, a favourite of King Edward IV of England (age 27), younger brother of Edward's (age 27) great friend William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 39).

In 1471 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 40) was appointed Lieutenant Calais.

Around 1471 [his daughter] Anne Hastings Countess Shrewsbury and Waterford was born to William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 40) and [his wife] Katherine Neville Baroness Bonville and Hastings (age 29). She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

In 1471 [his sister-in-law] Eleanor Neville Baroness Stanley (age 24) died. She was buried at St James Garlickhythe Vintry.

In 1471 William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 40) was appointed Chamberlain of the Exchequer.

On 14 Mar 1471 King Edward IV of England (age 28) landed at Ravenspur [Map] with William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 40).

On 14 Apr 1471 Edward IV (age 28) commanded at the Battle of Barnet supported by his brothers George (age 21) and Richard (age 18), John Babington (age 48), Wiliam Hastings (age 40) (commanded), [his brother] Ralph Hastings, William Norreys (age 30), William Parr (age 37), John Savage (age 49), William Bourchier Viscount Bourchier (age 41), Thomas St Leger (age 31), John Tuchet 6th Baron Audley, 3rd Baron Tuchet (age 45), Thomas Burgh 1st Baron Burgh (age 40), John Scott Comptroller (age 48) and Thomas Strickland.

The Yorkists William Blount (age 29), Humphrey Bourchier (age 40), Humphrey Bourchier (age 36), Henry Stafford (age 46) and Thomas Parr were killed.

The Lancastrians ...

[his brother-in-law] Warwick the Kingmaker (age 42) was killed. Earl Salisbury forfeit on the assumption he was attainted either before or after his death; the date of his attainder is unknown. If not attainted the Earldom may be in abeyance. Baron Montagu and Baron Montagu abeyant between his two daughters Isabel Neville Duchess Clarence (age 19) and Anne Neville Queen Consort England (age 14).

[his brother-in-law] John Neville 1st Marquess Montagu (age 40) was killed. Marquess Montagu extinct. He was buried at Bisham Abbey [Map].

William Tyrrell was killed.

William Fiennes 2nd Baron Saye and Sele (age 43) was killed. His son Henry Fiennes 3rd Baron Saye and Sele (age 25) succeeded 3rd Baron Saye and Sele. Anne Harcourt Baroness Saye and Sele by marriage Baroness Saye and Sele.

Henry Holland 3rd Duke Exeter (age 40) commanded the left flank, was badly wounded and left for dead, Henry Stafford (age 46) and John Paston (age 27) were wounded, John de Vere 13th Earl of Oxford (age 28) commanded, and John Paston (age 29) and William Beaumont 2nd Viscount Beaumont (age 33) fought.

Robert Harleston (age 36) was killed.

Thomas Hen Salusbury (age 62) was killed.

Thomas Tresham (age 51) escaped but was subsequently captured and executed on 06 May 1471.

On 04 May 1471 King Edward IV of England (age 29) was victorious at the Battle of Tewkesbury. His brother Richard (age 18), Richard Beauchamp 2nd Baron Beauchamp Powick (age 36), John Howard 1st Duke of Norfolk (age 46), George Neville 4th and 2nd Baron Bergavenny (age 31), John Savage (age 49), John Savage (age 27), Thomas St Leger (age 31), John Tuchet 6th Baron Audley, 3rd Baron Tuchet (age 45), Thomas Burgh 1st Baron Burgh (age 40) fought. William Brandon (age 46), George Browne (age 31), [his brother] Ralph Hastings, [his brother] Richard Hastings Baron Willoughby (age 38), James Tyrrell (age 16), Roger Kynaston of Myddle and Hordley (age 38) were knighted. William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 40) commanded.

Margaret of Anjou (age 41) was captured. Her son Edward of Westinster Prince of Wales (age 17) was killed. He was the last of the Lancastrian line excluding the illegitmate Charles Somerset 1st Earl of Worcester (age 11) whose line continues to the present.

John Courtenay 15th Earl Devon (age 36) was killed and attainted. Earl Devon, Baron Courtenay forfeit. Some sources refer to these titles as being abeyant?

John Wenlock 1st Baron Wenlock (age 71) was killed. Baron Wenlock extinct.

John Delves (age 49), Humphrey Tuchet (age 37), John Beaufort (age 30), William Vaux of Harrowden (age 35) and Robert Whittingham (age 42) were killed.

Edmund Beaufort 3rd Duke Somerset (age 32) and Hugh Courtenay (age 44) were captured.

Henry Roos fought and escaped to Tewkesbury Abbey [Map] where he sought sanctuary. He was subsequently pardoned.

On 05 Sep 1474 Thomas Grey 1st Marquess Dorset (age 19) and [his step-daughter] Cecily Bonville Marchioness Dorset (age 14) were married. He the son of John Grey and Elizabeth Woodville Queen Consort England (age 37). They were half second cousin once removed. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

On 29 Aug 1475 Edward IV (age 33) signed the Treaty of Picquigny; in effect a non-aggression pact or, possibly, a protection racket. France would pay Edward a pension of 50,000 crowns per year as long as he didn't invade France. Cardinal Bourchier (age 57) arbitrated on behalf of Edward. William Hastings (age 44) received a pension of 2000 crowns per year, John Howard and Thomas Montgomery 1200 each, Thomas Rotherham Archbishop of York (age 52) 1000, Cardinal John Morton (age 55) 600.

Edward's youngest brother Richard (age 22) opposed the Treaty considering it dishonourable. Roger Cheney (age 33) was present at the signing, and remained as a hostage until King Edward IV of England (age 33) returned to England.

On 04 Sep 1475 [his son] Edward Hastings 2nd Baron Hastings Baron Botreaux, Hungerford and Moleyns (age 8) and [his daughter-in-law] Mary Hungerford Baroness Hastings, 4th Baroness Hungerford, 5th Baroness Botreaux and 2nd Baroness Moleyns (age 9) were married. They were second cousin once removed. He a great x 3 grandson of King Edward III of England. She a great x 4 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

On 29 Jul 1476 Edward I's paternal grand-father Edward of York, Richard of York and his younger brother Edmund were reburied at St Mary and All Saints in Fotheringhay [Map] in a ceremony attended by King Edward IV of England (age 34), George York 1st Duke of Clarence (age 26), Thomas Grey 1st Marquess Dorset (age 21), William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 45), Anthony Woodville 2nd Earl Rivers (age 36).

Thomas Whiting, Chester Harald wrote:

n 24 July [1476] the bodies were exhumed, that of the Duke, "garbed in an ermine furred mantle and cap of maintenance, covered with a cloth of gold" lay in state under a hearse blazing with candles, guarded by an angel of silver, bearing a crown of gold as a reminder that by right the Duke had been a king. On its journey, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, with other lords and officers of arms, all dressed in mourning, followed the funeral chariot, drawn by six horses, with trappings of black, charged with the arms of France and England and preceded by a knight bearing the banner of the ducal arms. Fotheringhay was reached on 29 July, where members of the college and other ecclesiastics went forth to meet the cortege. At the entrance to the churchyard, King Edward waited, together with the Duke of Clarence, the Marquis of Dorset, Earl Rivers, Lord Hastings and other noblemen. Upon its arrival the King 'made obeisance to the body right humbly and put his hand on the body and kissed it, crying all the time.' The procession moved into the church where two hearses were waiting, one in the choir for the body of the Duke and one in the Lady Chapel for that of the Earl of Rutland, and after the King had retired to his 'closet' and the princes and officers of arms had stationed themselves around the hearses, masses were sung and the King's chamberlain offered for him seven pieces of cloth of gold 'which were laid in a cross on the body.' The next day three masses were sung, the Bishop of Lincoln preached a 'very noble sermon' and offerings were made by the Duke of Gloucester and other lords, of 'The Duke of York's coat of arms, of his shield, his sword, his helmet and his coursers on which rode Lord Ferrers in full armour, holding in his hand an axe reversed.' When the funeral was over, the people were admitted into the church and it is said that before the coffins were placed in the vault which had been built under the chancel, five thousand persons came to receive the alms, while four times that number partook of the dinner, served partly in the castle and partly in the King's tents and pavilions. The menu included capons, cygnets, herons, rabbits and so many good things that the bills for it amounted to more than three hundred pounds.

Calendars. 15 Feb 1478. Charter to the king's nephew Edward Plantagenet (age 4), first-born son of the said duke (age 25), creating him earl of Salisbury, with remainder to the heirs of his body, and granting to him and his said heirs £20 yearly from the issues of the county of Wilts. Witnesses: Th. cardinal archbishop of Canterbury (age 60), L. archbishop of York (age 58), Th. Bishop of Lincoln (age 54), the chancellor, J. Bishop of Rochester, keeper of the privy seal, Richard, duke of Gloucester (age 25), Henry, duke of Buckingham (age 23), Henry, Earl of Essex (age 74), treasurer of England, Anthony Earl of Ryvers (age 38), chief butler of England, and Thomas Stanley of Stanley (age 43), steward of the household, and William Hastynges of Hastynges (age 47), chamberlain of the household, knights. By p.s.

On 27 Jun 1481 [his son-in-law] George Talbot 4th Earl of Shrewsbury (age 13) and [his daughter] Anne Hastings Countess Shrewsbury and Waterford (age 10) were married. She by marriage Countess of Shrewsbury, Countess Waterford. He the son of John Talbot 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury and Catherine Stafford Countess Shrewsbury and Waterford. They were second cousins. He a great x 3 grandson of King Edward III of England. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

On 25 Mar 1483 King Edward IV of England (age 40) returned to Westminster [Map] from Windsor [Map]. A few days later he became sufficiently unwell to add codicils to his will, and to have urged reconciliation between William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 52) and Thomas Grey 1st Marquess Dorset (age 28); it isn't clear what the cause of the friction between the two men was although it appears well known that Hastings resented the Woodville family.

On 09 Apr 1483 King Edward IV of England (age 40) died at Westminster [Map]. His son King Edward V of England (age 12) succeeded V King England. Those present included Elizabeth Woodville Queen Consort England (age 46), William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 52) and Thomas Grey 1st Marquess Dorset (age 28).

The History of King Richard the Third by Thomas More. When these lords [Note. William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 52), John Grey] with diverse others of both parties were come into his presence, the King (age 40), lifting up himself and propped up with pillows, as it is reported, after this fashion said unto them:

My lords, my dear kinsmen and allies, in what plight I lie, you see, and I feel. By which, the less while I expect to live with you, the more deeply am I moved to care in what case I leave you, for such as I leave you, such be my children like to find you. That if they should (God forbid) find you at variance, might by chance fall themselves at war before their discretion would serve to set you at peace. You see their youth, of which I reckon the only security to rest in your concord. For it suffices not that all you love them, if each of you hate the other. If they were men, your faithfulness by chance would suffice. But childhood must be maintained by men's authority, and slippery youth supported with elder counsel, which neither they can have unless you give it, nor can you give it if you do not agree. For where each labors to break what the other makes, and for hatred of each other's person impugns each other's counsel, it must needs be long before any good conclusion go forward. And also while either party labors to be chief, flattery shall have more place than plain and faithful advice, of which must needs ensue the evil bringing up of the Prince, whose mind in tender youth infected shall readily fall to mischief and riot, and draw down with this noble realm to ruin-unless grace turn him to wisdom, which if God send, then they who by evil means before pleased him best shall after fall furthest out of favor, so that ever at length evil plans drive to nothing and good plain ways prosper.

On 17 Apr 1483 the coffin of Edward IV (deceased) was carried to Westminster Abbey [Map] by Edward Stanley 1st Baron Monteagle (age 21), John Savage (age 39), Thomas Wortley (age 50), Thomas Molyneux (age 38), probably John Welles 1st Viscount Welles (age 33) who had married Edward's daughter Cecily), John Cheney 1st Baron Cheyne (age 41), Walter Hungerford (age 19), Guy Wolston (age 50), John Sapcote (age 35), Thomas Tyrrell (age 30), John Risley, Thomas Dacre 2nd Baron Dacre Gilsland (age 15), John Norreys, Louis de Bretelles and John Comyn 4th Lord Baddenoch.

Those in the procession included:

Thomas St Leger (age 43), widow of Edward's sister Anne.

William Stonor (age 33).

Henry Ferrers (age 40).

James Radclyffe (age 43).

George Browne (age 43).

Gilbert Debenham (age 51).

John Howard 1st Duke of Norfolk (age 58) walked in front of the coffin with Edward's personal arms.

John Marlow Abbot Bermondsey followed by:

Bishop Thomas Kempe (age 93).

Bishop John Hales (age 83) (Bishop of Chester?).

Bishop Robert Stillington (age 63).

Bishop Edward Story.

Bishop William Dudley (age 58).

Cardinal John Morton (age 63) (as Bishop of Ely).

Bishop Edmund Tuchet (age 40) (as Bishop of Rochester).

Bishop Peter Courtenay, and.

Bishop Lionel Woodville (age 36).

Archbishop Thomas Rotherham (age 59) brought up the rear.

Cardinal Thomas Bourchier (age 65), then Archbishop of Canterbury, took no part due to infirmity.

John de la Pole 1st Earl Lincoln (age 21); the King's nephew,.

William Hastings 1st Baron Hastings (age 52).

Thomas Grey 1st Marquess Dorset (age 28).

William Herbert 2nd Earl Pembroke 1st Earl Huntingdon (age 32) (some sources say Earl of Huntingindon?).

William Berkeley 1st Marquess Berkeley (age 57).

Thomas Stanley 1st Earl of Derby (age 48).

Richard Fiennes 7th Baron Dacre Gilsland (age 68).

John Dudley 1st Baron Dudley (age 82).

George Neville 4th and 2nd Baron Bergavenny (age 43).

John Tuchet 6th Baron Audley, 3rd Baron Tuchet (age 57).

Walter Devereux Baron Ferrers of Chartley (age 51).

Edward Grey 1st Viscount Lisle (age 51).

Henry Lovell 9th Baron Marshal 8th Baron Morley (age 7).

Richard Woodville 3rd Earl Rivers (age 30).

John Brooke 7th Baron Cobham (age 35).

[his brother] Richard Hastings Baron Willoughby (age 50).

The History of King Richard the Third by Thomas More. But then, by and by, the lords assembled together at London. To ward which meeting, the Archbishop of York (age 59), fearing that it would be ascribed (as it was indeed) to his overmuch lightness that he so suddenly had yielded up the Great Seal to the Queen-to whom the custody thereof nothing pertained without special commandment of the King-secretly sent for the Seal again and brought it with him after the customary manner. And at this meeting, the Duke of Buckingham, whose loyalty toward the King no man doubted nor needed to doubt, persuaded the lords to believe that the Duke of Gloucester (age 30) was sure and fastly faithful to his Prince and that the Lord Rivers (age 43) and Lord Richard (age 26) with the other knights were, for matters attempted by them against the Dukes of Gloucester and Buckingham, put under arrest for the dukes' safety not for the King's jeopardy and that they were also in safeguard and should remain there no longer till the matter were, not by the dukes only but also by all the other lords of the King's Council indifferently examined and by other discretions ordered, and either judged or appeased. But one thing he advised them beware, that they judged not the matter too far forth before they knew the truth-for by turning their private grudges into the common hurt, irritating and provoking men unto anger, and disturbing the King's coronation, toward which the dukes were coming up, they might perhaps bring the matter so far out of joint, that it should never be brought in frame again. This strife, if it should happen to come to battle, as it was likely, though both parties were in all things equal, yet should the authority be on that side where the King is himself.

With these arguments of the Duke of Buckingham - part of which he believed; part, he knew the contrary - these commotions were somewhat appeased, but especially because the Dukes of Gloucester and Buckingham (age 28) were so near, and came so quickly on with the King, in none other manner, with none other voice or semblance, than to his coronation, causing the story to be blown about that those lords and knights who were taken had contrived the destruction of the Dukes of Gloucester and Buckingham (age 28) and of other noble blood of the realm, to the end that they themselves would alone manage and govern the King at their pleasure. And for the false proof thereof, some of the dukes' servants rode with the carts of the stuff that were taken (among such stuff, no marvel, but that some of it were armor, which, at the breaking up of that household, must needs either be brought away or cast away), and they showed it unto the people all the way as they went: "Lo, here be the barrels of armor that these traitors had privately conveyed in their carriage to destroy the noble lords withal." This device, although it made the matter to wise men more unlikely, who well perceived that, if the intenders meant war, they would rather have had their armor on their backs than to have bound them up in barrels, yet much part of the common people were therewith very well satisfied, and said it were like giving alms to hang them.

When the King approached near to the city, Edmund Shaa (age 47), goldsmith then mayor, with William White and John Mathew, sheriffs, and all the other aldermen in scarlet, with five hundred horse of the citizens in violet, received him reverently at Hornsey, and riding from thence, accompanied him in to the city, which he entered the fourth day of May, the first and last year of his reign.

But the Duke of Gloucester bore himself in open sight so reverently to the Prince, with all semblance of lowliness, that from the great obloquy in which he was so late before, he was suddenly fallen in so great trust, that at the Council next assembled, he was the only man chosen and thought most suitable to be Protector (age 30) of the King and his realm, so that-were it destiny or were it folly-the lamb was given to the wolf to keep. At which Council also the Archbishop of York (age 59), Chancellor of England, who had delivered up the Great Seal to the Queen (age 46), was thereof greatly reproved, and the Seal taken from him and delivered to Doctor Russell, Bishop of Lincoln, a wise man and good and of much experience, and one of the best learned men undoubtedly that England had in his time. Diverse lords and knights were appointed unto diverse offices. The Lord Chamberlain and some others kept still their offices that they had before.

Now all was such that the Protector (age 30) so sore thirsted for the finishing of what he had begun-though he thought every day a year till it were achieved-yet he dared no further attempt as long as he had but half his prey in hand, well knowing that if he deposed the one brother, all the realm would fall to the other, if he either remained in sanctuary or should by chance be shortly conveyed farther away to his liberty.

Wherefore straight away at the next meeting of the lords at the Council, he proposed unto them that it was a heinous deed of the Queen (age 46), and proceeding from great malice toward the King's counselors, that she should keep in sanctuary the King's brother from him, whose special pleasure and comfort were to have his brother with him. And that by her such was done to no other intent, but to bring all the lords in obloquy and murmur of the people, as though they were not to be trusted with the King's brother-they who were, by the assent of the nobles of the land, appointed as the King's nearest friends for the protection of his own royal person.

"The prosperity whereof stands," said he, "not all in keeping from enemies or ill viands, [poison?] but partly also in recreation and moderate pleasure, which he cannot in this tender youth take in the company of elder persons, but in the familiar conversation of those who be neither far under nor far above his age, and nevertheless of state appropriate to accompany his noble majesty. Wherefore with whom rather than with his own brother? And if any man think this consideration light (which I think no man thinks who loves the King), let him consider that sometimes without small things, greater cannot stand. And verily it redounds greatly to the dishonor both of the King's Highness and of all us that have been about his Grace, to have it run in every man's mouth, not in this realm only, but also in other lands (as evil words walk far), that the King's brother should be glad to keep sanctuary. For every man will suppose that no man will so do for nothing. And such evil opinion, once fastened in men's hearts, hard it is to wrest out, and may grow to more grief than any man here can divine.

"Wherefore I think it were not worst to send unto the Queen (age 46) for the redress of this matter some honorable trusty man, such as both values the King's welfare and the honor of his Council, and is also in favor and credible with her. For all which considerations, none seems to me more suitable than our reverent father here present, my Lord Cardinal (age 65), who may in this matter do most good of any man, if it please him to take the pain. Which I doubt not of his goodness he will not refuse, for the King's sake and ours, and the well being of the young Duke himself, the King's most honorable brother, and after my Sovereign Lord himself, my most dear nephew, considering that thereby shall be ceased the slanderous rumor and obloquy now going about, and the hurts avoided that thereof might ensue, and much rest and quiet grow to all the realm.

"And if she be perchance so obstinate, and so precisely set upon her own will that neither his wise and faithful instruction can move her, nor any man's reason content her, then shall we, by mine advice, by the King's authority, fetch him out of that prison, and bring him to his noble presence, in whose continual company he shall be so well cherished and so honorably treated that all the world shall to our honor, and her reproach, perceive that it was only malice, audacity, or folly, that caused her to keep him there. This is my mind in this matter for this time, except any of your lordships anything perceive to the contrary. For never shall I by God's grace so wed myself to mine own will, but that I shall be ready to change it upon your better advice."

When the Protector (age 30) had spoken, all the Council affirmed that the motion was good and reasonable, and to the King and the Duke his brother, honorable, and a thing that should cease great murmur in the realm, if the mother might be by good means induced to deliver him. Such a thing the Archbishop of Canterbury (age 65), whom they all agreed also to be thereto most appropriate, took upon himself to move her, and therein to give his uttermost best effort. However, if she could be in no way entreated with her good will to deliver him, then thought he and such others as were of the clergy present that it were not in any way to be attempted to take him out against her will. For it would be a thing that should turn to the great grudge of all men, and high displeasure of God, if the privilege of the holy place should now be broken, which had so many years been kept, and which both king and popes so good had granted, so many had confirmed, and which holy ground was more than five hundred years ago by Saint Peter, his own person come in spirit by night, accompanied with great multitude of angels, so specially hallowed and dedicated it to God (for the proof whereof they have yet in the Abbey Saint Peter's cloak to show) that from that time forward was there never so undevout a king who dared that sacred place to violate, or so holy a bishop that dared presume to consecrate.

"And therefore," said the Archbishop of Canterbury, "God forbid that any man should for any earthly enterprise break the immunity and liberty of that sacred sanctuary that has been the safeguard of so many a good man's life. And I trust," said he, "with God's grace, we shall not need it. But for any manner need, I would not we should do it. I trust that she shall be with reason contented, and all things in good manner obtained. And if it happen that I bring it not so to pass, yet shall I toward it so far forth do my best, that you shall all well perceive that no lack of my dutiful efforts, but the mother's dread and womanish fear, shall be the impediment."

"Womanish fear, nay womanish perversity," said the Duke of Buckingham. "For I dare take it upon my soul, she well knows she needs no such thing to fear, either for her son or for herself. For as for her, here is no man that will be at war with women. Would God some of the men of her kin were women too, and then should all be soon at rest. However, there is none of her kin the less loved for that they be her kin, but for their own evil deserving. And nevertheless, if we loved neither her nor her kin, yet were there no cause to think that we should hate the King's noble brother, to whose Grace we ourself be of kin. Whose honor, if she as much desired as our dishonor and as much regard took to his well being as to her own will, she would be as loath to suffer him from the King as any of us be. "For if she have any wit (as would God she had as good will as she has shrewd wit), she reckons herself no wiser than she thinks some that be here, of whose faithful mind, she nothing doubts, but verily believes and knows that they would be as sorry of his harm as herself, and yet would have him from her if she abide there. And we all, I think, are satisfied that both be with her, if she come thence and abide in such place where they may with their honor be.

"Now then, if she refuse in the deliverance of him, to follow the counsel of them whose wisdom she knows, whose truth she well trusts, it is easy to perceive that perversity hinders her, and not fear. But go to, suppose that she fear (as who may let her to fear her own shadow), the more she fears to deliver him, the more ought we fear to leave him in her hands. For if she cast such fond doubts that she fear his hurt, then will she fear that he shall be fetched thence. For she will soon think that if men were set (which God forbid) upon so great a mischief, the sanctuary would little impede them, for good men might, as I think, without sin somewhat less regard it than they do.

"Now then, if she doubt lest he might be fetched from her, is it not likely enough that she shall send him somewhere out of the realm? Verily, I look for none other. And I doubt not but she now thinks with great exertion on it, even as we consider the hindrance of sanctuary. And if she might happen to bring that to pass (as it were no great accomplishment, we letting her alone), all the world would say that we were a wise sort of counselors about a King-we that let his brother be cast away under our noses. And therefore I assure you faithfully for my mind, I will rather defy her plans, fetch him away, than leave him there, till her perversity or fond fear convey him away. "And yet will I break no sanctuary therefore. For verily since the privileges of that place and other like have been of long continued, I am not he that would be about to break them. And in good faith if they were now to begin, I would not be he that should be about to make them. Yet will I not say nay, but that it is a deed of pity that such men of the sea or their evil debtors have brought in poverty, should have some place of liberty, to keep their bodies out of the danger from their cruel creditors. And also if the Crown happen (as it has done) to come in question, while either part takes the other as traitors, I will well there be some places of refuge for both. But as for thieves, of which these places be full, and which never fall from the craft after they once fall thereto, it is pity the sanctuary should serve them. And much more murderers whom God bade to take from the altar and kill them, if their murder were willful. And where it is otherwise there need we not the sanctuaries that God appointed in the old law. For if either necessity, his own defense or misfortune draw him to that deed, a pardon serves which either the law grants of course, or the King of pity may.

"Then look me now how few sanctuary men there be whom any favorable necessity compelled to go thither. And then see on the other side what a sort there be commonly therein, of them whom willful prodigality has brought to nought. What a rabble of thieves, murderers, and malicious, heinous traitors, and that in two places specially: the one at the elbow of the city, the other in the very bowels. I dare well avow it. Weigh the good that they do with the hurt that comes of them, and you shall find it much better to lack both, than have both. And this I say, although they were not abused as they now be, and so long have been, that I fear me ever they will be while men be afraid to set their hands to the amendment: as though God and Saint Peter were the patrons of ungracious living.

"Now prodigals riot and run in debt upon the boldness of these places; yea, and rich men run thither with poor men's goods; there they build, there they spend and bid their creditors go whistle them. Men's wives run thither with their husbands' money, and say they dare not abide with their husbands for beating. Thieves bring thither their stolen goods, and there live thereon. There devise they new robberies; nightly they steal out, they rob and pillage and kill, and come in again as though those places gave them not only a safeguard for the harm they have done, but a license also to do more. However, much of this mischief, if wise men would set their hands to it, might be amended with great thanks to God and no breach of the privilege. The residue, since so long ago I knew never what pope and what prince more piteous than prudent has granted it, and other men because of a certain religious fear have not broken it, let us take a pain therewith, and let it in God's name stand in force, as far forth as reason will. Which is not fully so far forth as may serve to prevent us from fetching forth this noble man to his honor and wealth, out of that place in which he neither is nor can be a sanctuary man.

"A sanctuary serves always to defend the body of that man that stands in danger abroad, not of great hurt only, but also of lawful hurt. For against unlawful harms, never pope nor king intended to privilege any one place. For that privilege has every place. Know you any man any place wherein it is lawful for one man to do another wrong? That no man unlawfully take hurt, that liberty, the King, the law, and very nature forbid in every place and make to that regard for every man a sanctuary every place. But where a man is by lawful means in peril, there needs he the protection of some special privilege, which is the only ground and cause of all sanctuaries. From which necessity this noble prince is far. His love to his King, nature and kindred prove, whose innocence to all the world his tender youth proves. And so sanctuary as for him, neither none he needs, nor also none can have.

"Men come not to sanctuary as they come to baptism, to require it by their godfathers. He must ask it himself that must have it. And what reason-since no man has cause to have it but whose conscience of his own fault makes him feign need to require it-what reason then will yonder babe have? which, even if he had discretion to require it, if need were, I dare say would now be right angry with them that keep him there. And I would think without any scruple of conscience, without any breach of privilege, to be somewhat more homely with them that be there sanctuary men indeed. For if one go to sanctuary with another man's goods, why should not the King, leaving his body at liberty, satisfy the part of his goods even within the sanctuary? For neither king nor pope can give any place such a privilege that it shall discharge a man of his debts, being able to pay."

And that diversity of the clergy that were present, whether they said it for his pleasure or, as they thought, agreed plainly that by the law of God and of the church the goods of a sanctuary man should be delivered in payment of his debts, and stolen goods to the owner, and only liberty reserved him to get his living with the labor of his hands.

"Verily," said the Duke, "I think you say very truth. And what if a man's wife will take sanctuary because she wishes to run from her husband? I would think if she can allege none other cause, he may lawfully-without any displeasure to Saint Peter-take her out of Saint Peter's church by the arm. And if nobody may be taken out of sanctuary that says he will abide there, then if a child will take sanctuary because he fears to go to school, his master must let him alone. And as simple as that example is, yet is there less reason in our case than in that. For therein, though it be a childish fear, yet is there at the leastwise some fear. And herein is there none at all. And verily I have often heard of sanctuary men. But I never heard before of sanctuary children. And therefore, as for the conclusion of my mind, whosoever may have deserved to need it, if they think it for their safety, let them keep it. But he can be no sanctuary man that neither has wisdom to desire it nor malice to deserve it, whose life or liberty can by no lawful process stand in jeopardy. And he that takes one out of sanctuary to do him good, I say plainly that he breaks no sanctuary."

When the Duke had done, the laymen entire and a good part of the clergy also, thinking no earthly hurt was meant toward the young babe, agreed in effect that, if he were not delivered, he should be fetched. However, they all thought it best, in the avoiding of all manner of rumor, that the Lord Cardinal should first attempt to get him with her good will. And thereupon all the Council came unto the Star Chamber at Westminster. And the Lord Cardinal, leaving the Protector (age 30) with the Council in the Star Chamber, departed into the sanctuary to the Queen (age 46) with diverse other lords with him-were it for the respect of his honor, or that she should by presence of so many perceive that this errand was not one man's mind, or were it for that the Protector (age 30) intended not in this matter to trust any one man alone, or else, if she finally were determined to keep him, some of that company had perhaps secret instruction immediately, despite her mind, to take him and to leave her no chance to take him away, which she was likely to plan after this matter was revealed to her, if her time would in any way serve her.

When the Queen (age 46) and these lords were come together in presence, the Lord Cardinal showed unto her that it was thought by the Protector (age 30) and the whole Council that her keeping of the King's brother in that place was the thing which highly sounded, not only to the great rumor of the people and their obloquy, but also to the unbearable grief and displeasure of the King's royal majesty; to whose Grace it were as singular comfort to have his natural brother in company, as it was to both their dishonor and all theirs and hers also, to suffer him in sanctuary-as though the one brother stood in danger and peril of the other. And he showed her that the Council therefore had sent him unto her to require her the delivery of him that he might be brought unto the King's presence at his liberty, out of that place that they reckoned as a prison. And there should he be treated according to his estate. And she in this doing should both do great good to the realm, pleasure to the Council and profit to herself, assistance to her friends that were in distress, and over that (which he knew well she specially valued), not only great comfort and honor to the King, but also to the young Duke himself, for both of them great wealth it were to be together, as well for many greater causes, as also for their both entertainment and recreation; which thing the lords esteemed not slight, though it seem light, well pondering that their youth without recreation and play cannot endure, nor find any stranger according to the propriety of both their ages and estates so suitable in that point for any of them as either of them for the other.

"My lord," said the Queen (age 46), "I say not nay, but that it were very appropriate that this gentleman whom you require were in the company of the King his brother. And in good faith I think it were as great advantage to them both, as for yet a while, to be in the custody of their mother, the tender age considered of the elder of them both, but especially the younger, who besides his infancy that also needs good looking to, has awhile been so sore diseased, vexed with sickness, and is so newly rather a little amended than well recovered, that I dare put no earthly person in trust with his keeping but myself alone, considering, that there is, as physicians say, and as we also find, double the peril in the relapse that was in the first sickness, with which disease-nature being forelabored, forewearied and weakened-grows the less able to bear out a new excess of the illness. And although there might be found another who would by chance do their best unto him, yet is there none that either knows better how to order him than I that so long have kept him; or is more tenderly like to cherish him than his own mother that bore him."

"No man denies, good Madam," said the Cardinal, "but that your Grace were of all folk most necessary about your children, and so would all the Council not only be content but also glad that you were, if it might stand with your pleasure to be in such place as might stand with their honor. But if you appoint yourself to tarry here, then think they yet more apt that the Duke of York were at his liberty honorably with the King-to the comfort of them both than here as a sanctuary man to both their dishonor and obloquy. Since there is not always so great necessity to have the child be with the mother, but that occasion may sometime be such that it should be more expedient to keep him elsewhere. Which in this well appears that, at such time as your dearest son, then Prince and now King, should for his honor and good order of the country, keep household in Wales far out of your company, your Grace was well content therewith yourself."

"Not very well content," said the Queen (age 46), "and yet the case is not like: for the one was then in health, and the other is now sick. In which case I marvel greatly that my Lord Protector (age 30) is so desirous to have him in his keeping, where if the child in his sickness miscarried by nature, yet might he run into slander and suspicion of fraud. And where they call it a thing so sore against my child's honor and theirs also that he abides in this place, it is all their honors there to suffer him abide where no man doubts he shall be best kept. And that is here, while I am here, which as yet I intend not to come forth and jeopardize myself after the fashion of my other friends, who, would God, were here in surety with me rather than I were there in jeopardy with them."

"Why, Madam," said another lord, "know you anything why they should be in jeopardy?"

"Nay, verily, Sir," said she, "nor why they should be in prison neither, as they now be. But it is, I trust, no great marvel, though I fear lest those that have not omitted to put them in duress without falsity will omit as little to procure their destruction without cause." The Cardinal made a countenance to the other lord that he should harp no more upon that string. And then said he to the Queen (age 46) that he nothing doubted but that those lords of her honorable kin, who as yet remained under arrest should, upon the matter examined, do well enough. And as toward her noble person, neither was nor could be any manner of jeopardy.

"Whereby should I trust that?" said the Queen (age 46). "In that I am guiltless? As though they were guilty. In that I am with their enemies better beloved than they? When they hate them for my sake. In that I am so near of kin to the King? And how far be they away, if that would help, as God send grace it hurt not. And therefore as for me, I purpose not as yet to depart hence. And as for this gentleman my son, I mind that he shall be where I am till I see further. For I assure you, because I see some men so greedy without any substantial cause to have him, this makes me much the more further from delivering him."

"Truly, madam," said he, "and the further that you be to deliver him, the further be other men to suffer you to keep him, lest your causeless fear might cause you farther to convey him. And many be there that think that he can have no privilege in this place, who neither can have will to ask it, nor malice to deserve it. And therefore they reckon no privilege broken, though they fetch him out, which, if you finally refuse to deliver him, I verily think they will (so much dread has my Lord, his uncle, for the tender love he bears him), lest your Grace should by chance send him away."

"Ah, sir," said the Queen (age 46), "has the Protector (age 30) so tender zeal to him that he fears nothing but lest he should escape him? Thinks he that I would send him hence, which neither is in the plight to send out, and in what place could I reckon him sure, if he be not sure in this the sanctuary, whereof there was never tyrant yet so devilish that dared presume to break. And, I trust God, the most holy Saint Peter-the guardian of this sanctuary-is as strong now to withstand his adversaries as ever he was.

"But my son can deserve no sanctuary, and therefore he cannot have it. Forsooth he has found a goodly gloss by which that place that may defend a thief may not save an innocent. But he is in no jeopardy nor has no need thereof. Would God he had not. Trusts the Protector (age 30) (I pray God he may prove a Protector (age 30)), trusts he that I perceive not whereunto his painted process draws? He says it is not honorable that the Duke abide here and that it were comfortable for them both that he were with his brother because the King lacks a playfellow. Be you sure. I pray God send them both better playfellows than him who makes so high a matter upon such a trifling pretext-as though there could none be found to play with the King unless his brother, who has no lust to play because of sickness, come out of sanctuary, out of his safeguard, to play with him. As though princes as young as they be could not play but with their peers, or children could not play but with their kindred, with whom for the most part they agree much worse than with strangers.

"But the child cannot require the privilege-who told him so? He shall hear him ask it, if he will. However, this is a gay matter: Suppose he could not ask it; suppose he would not ask it; suppose he would ask to go out. If I say he shall not, if I ask the privilege but for myself, I say he that against my will takes out him, breaks the sanctuary. Serves this liberty for my person only, or for my goods too? You may not hence take my horse from me, and may you take my child from me? He is also my ward, for as my learned Council shows me, since he has nothing by descent held by knight's service, the law makes his mother his guardian. Then may no man, I suppose, take my ward from me out of sanctuary, without the breech of the sanctuary. And if my privilege could not serve him, nor he ask it for himself, yet since the law commits to me the custody of him, I may require it for him-unless the law give a child a guardian only for his goods and his lands, discharging him of the care and safekeeping of his body, for which only both lands and goods serve.

"And if examples be sufficient to obtain privilege for my child, I need not far to seek. For in this place in which we now be (and which is now in question whether my child may take benefit of it) mine other son, now King, was born and kept in his cradle and preserved to a more prosperous fortune, which I pray God long to continue. And as all you know, this is not the first time that I have taken sanctuary, for when my lord, my husband, was banished and thrust out of his kingdom, I fled hither being great with child, and here I bore the Prince. And when my lord, my husband, returned safe again and had the victory, then went I hence to welcome him home, and from hence I brought my babe the Prince unto his father, when he first took him in his arms. And I pray God that my son's palace may be as great safeguard to him now reigning, as this place was sometime to the King's enemy. In which place I intend to keep his brother.

"Wherefore here intend I to keep him because man's law serves the guardian to keep the infant. The law of nature wills the mother keep her child. God's law privileges the sanctuary, and the sanctuary my son, since I fear to put him in the Protector's (age 30) hands that has his brother already; and if both princes failed, the Protector (age 30) were inheritor to the crown. The cause of my fear has no man to do but examine. And yet fear I no further than the law fears, which, as learned men tell me, forbids every man the custody of them by whose death he may inherit less land than a kingdom. I can no more, but whosoever he be that breaks this holy sanctuary, I pray God shortly send him need of sanctuary, when he may not come to it. For taken out of sanctuary would I not my mortal enemy were."

The Lord Cardinal, perceiving that the Queen (age 46) grew ever longer the further off and also that she began to kindle and chafe and speak sore, biting words against the Protector (age 30), and such as he neither believed and was also loath to hear, he said unto her for a final conclusion that he would no longer dispute the matter. But if she were content to deliver the Duke to him and to the other lords there present, he dared lay his own body and soul both in pledge, not only for his safety but also for his estate. And if she would give them a resolute answer to the contrary, he would forthwith depart therewithal, and manage whosoever would with this business afterward; for he never intended more to move her in that matter in which she thought that he and all others, save herself, lacked either wit or truth-wit, if they were so dull that they could nothing perceive what the Protector (age 30) intended; truth, if they should procure her son to be delivered into his hands, in whom they should perceive toward the child any evil intended.

The Queen (age 46) with these words stood a good while in a great study. And forasmuch to her seemed the Cardinal more ready to depart than some of the remnant, and the Protector (age 30) himself ready at hand, so that she verily thought she could not keep him there, but that he should immediately be taken thence; and to convey him elsewhere, neither had she time to serve her, nor place determined, nor persons appointed, all things unready because this message came on her so suddenly, nothing less expecting than to have him fetched out of sanctuary, which she thought to be now beset in such places about that he could not be conveyed out untaken, and partly as she thought it might fortune her fear to be false, and so well she knew it was either needless or without remedy to resist; wherefore, if she should needs go from him, she thought it best to deliver him. And over that, of the Cardinal's faith she nothing doubted, nor of some other lords neither, whom she there saw, which as she feared lest they might be deceived, so was she well assured they would not be corrupted. Then thought she it should yet make them the more warily to look to him and the more circumspect to see to his safety, if she with her own hands gave him to them of trust. And at the last she took the young Duke by the hand, and said unto the lords:

"My Lord," said she, "and all my lords, I neither am so unwise to mistrust your wits, nor so suspicious to mistrust your truths. Of which thing I purpose to make you such a proof that, if either of both lacked in you, might turn both me to great sorrow, the realm to much harm, and you to great reproach. For, lo, here is," said she, "this gentleman, whom I doubt not but I could here keep safe if I would, whatsoever any man say. And I doubt not also but there be some abroad, so deadly enemies unto my blood, that if they knew where any of it lay in their own body, they would let it out.

"We have also had experience that the desire of a kingdom knows no kindred. The brother has been the brother's bane. And may the nephews be sure of their uncle? Each of these children is the other's defense while they be asunder, and each of their lives lies in the other's body. Keep one safe and both be sure, and nothing for them both more perilous than to be both in one place. For what wise merchant ventures all his goods in one ship?

"All this notwithstanding, here I deliver him and his brother in him-to keep into your hands-of whom I shall ask them both before God and the world. Faithful you be, that know I well, and I know well you be wise. Power and strength to keep him, if you wish, neither lack you of yourself, nor can lack help in this cause. And if you cannot elsewhere, then may you leave him here. But only one thing I beseech you for the trust that his father put in you ever, and for trust that I put in you now, that as far as you think that I fear too much, be you well wary that you fear not as far too little." And therewithal she said unto the child: "Farewell, my own sweet son. God send you good keeping. Let me kiss you once yet before you go, for God knows when we shall kiss together again." And therewith she kissed him, and blessed him, turned her back and wept

and went her way, leaving the child weeping as fast.

When the Lord Cardinal and these other lords with him had received this young duke, they brought him into the Star Chamber where the Protector (age 30) took him in his arms and kissed him with these words:

"Now welcome, my Lord, even with all my very heart." And he said in that of likelihood as he thought. Thereupon forthwith they brought him to the King, his brother, into the Bishop's Palace at Paul's, and from thence through the city honorably into the Tower, out of which after that day they never came abroad.

When the Protector (age 30) had both the children in his hands, he opened himself more boldly, both to certain other men, and also chiefly to the Duke of Buckingham, although I know that many thought that this Duke was privy to all the Protector's (age 30) counsel, even from the beginning.

And some of the Protector's (age 30) friends said that the Duke was the first mover of the Protector (age 30) to this matter, sending a private messenger unto him, straight after King Edward's death. But others again, who knew better the subtle cunning of the Protector (age 30), deny that he ever opened his enterprise to the Duke until he had brought to pass the things before rehearsed. But when he had imprisoned the Queen's (age 46) kinsfolks and gotten both her sons into his own hands, then he opened the rest of his purpose with less fear to them whom he thought meet for the matter, and specially to the Duke, who being won to his purpose, he thought his strength more than half increased.

The matter was broken unto the Duke by subtle folks, and such as were masters of their craft in the handling of such wicked devices, who declared unto him that the young king was offended with him for his kinsfolks' sakes, and that if he were ever able, he would revenge them, who would prick him forward thereunto if they escaped (for the Queen's (age 46) family would remember their imprisonment). Or else if his kinsfolk were put to death, without doubt the young king would be sorrowful for their deaths, whose imprisonment was grievous unto him. And that with repenting the Duke should nothing avail: for there was no way left to redeem his offense by benefits, but he should sooner destroy himself than save the King, who with his brother and his kinsfolks he saw in such places imprisoned, as the Protector (age 30) might with a nod destroy them all; and that it were no doubt but he would do it indeed, if there were any new enterprise attempted. And that it was likely that as the Protector (age 30) had provided private guard for himself, so had he spies for the Duke and traps to catch him if he should be against him, and that, perchance, from them whom he least suspected. The state of things and the dispositions of men were then such that a man could not well tell whom he might trust or whom he might fear. These things and such like, being beaten into the Duke's mind, brought him to that point where he had repented the way he had entered, yet would he go forth in the same; and since he had once begun, he would stoutly go through. And therefore to this wicked enterprise, which he believed could not be avoided, he bent himself and went through and determined that since the common mischief could not be amended, he would turn it as much as he might to his own advantage.

Then it was agreed that the Protector (age 30) should have the Duke's aid to make him king, and that the Protector's (age 30) only lawful son should marry the Duke's daughter, and that the Protector (age 30) should grant him the quiet possession of the Earldom of Hertford, which he claimed as his inheritance and could never obtain it in King Edward's time. Besides these requests of the Duke, the Protector (age 30) of his own mind promised him a great quantity of the King's treasure and of his household stuff. And when they were thus at a point between themselves, they went about to prepare for the coronation of the young king as they would have it seem. And that they might turn both the eyes and minds of men from perceiving their plans, the lords, being sent for from all parties of the realm, came thick to that solemnity.

But the Protector (age 30) and the Duke, after that, once they had set the Lord Cardinal, the Archbishop of York (then Lord Chancellor), the bishop of Ely (age 63), Lord Stanley, and Lord Hastings (age 52) (then Lord Chamberlain) with many other noble men to commune and devise about the coronation in one place, as fast were they in another place contriving the contrary, and to make the Protector (age 30) king. To which council, although there were admittedly very few, and they very secret, yet began there, here and there about, some manner of muttering among the people, as though all should not long be well, though they neither knew what they feared nor wherefore: Were it that before such great things, men's hearts of a secret instinct of nature misgives them, as the sea without wind swells of itself sometime before a tempest; or were it that some one man haply somewhat perceiving, filled many men with suspicion, though he showed few men what he knew. However, somewhat the dealing itself made men to muse on the matter, though the council was closed. For little by little all folk withdrew from the Tower and drew to Crosby's Place in Bishopsgate Street where the Protector (age 30) kept his household. The Protector (age 30) had the people appealing to him; the King was in manner alone. While some for their business made suit to them that had the doing, some were by their friends secretly warned that it might haply turn them to no good to be too much attendant about the King without the Protector's (age 30) appointment, who removed also many of the Prince's old servants from him, and set new ones about him. Thus many things coming together-partly by chance, partly by purpose-caused at length not only common people who wave with the wind, but also wise men and some lords as well, to mark the matter and muse thereon, so far forth that the Lord Stanley, who was afterwards Earl of Darby, wisely mistrusted it and said unto the Lord Hastings (age 52) that he much disliked these two several councils.

"For while we," said he, "talk of one matter in the one place, little know we whereof they talk in the other place."

"My Lord," said the Lord Hastings (age 52), "on my life, never doubt you. For while one man is there who is never thence, never can there be things once minded that should sound amiss toward me, but it should be in mine ears before it were well out of their mouths."

This meant he by Catesby, who was of his near secret counsel and whom he very familiarly used, and in his most weighty matters put no man in so special trust, reckoning himself to no man so dear, since he well knew there was no man to him so much beholden as was this Catesby, who was a man well learned in the laws of this land, and by the special favor of the Lord Chamberlain in good authority and much rule bore in all the county of Leicester where the Lord Chamberlain's power chiefly lay. But surely great pity was it that he had not had either more truth or less wit. For his dissimulation alone kept all that mischief up. If the Lord Hastings (age 52) had not put so special trust in Catesby, the Lord Stanley and he had departed with diverse other lords and broken all the dance, for many ill signs that he saw, which he now construed all to the best, so surely thought he there could be none harm toward him in that council intended where Catesby was. And of truth the Protector (age 30) and the Duke of Buckingham made very good semblance unto the Lord Hastings (age 52) and kept him much in company. And undoubtedly the Protector (age 30) loved him well and loath was to have lost him, saving for fear lest his life should have quelled their purpose. For which cause he moved Catesby to prove with some words cast out afar off, whether he could think it possible to win the Lord Hastings (age 52) to their part. But Catesby, whether he tried him or questioned him not, reported unto them that he found him so fast and heard him speak so terrible words that he dared no further say. And of truth the Lord Chamberlain, with great trust, showed unto Catesby the mistrust that others began to have in the matter.

Calendars. 20 May 1483 King Richard III of England (age 30). Westminster Palace [Map]. Grant for life to the king's servant William Hastings (age 52), knight, of the office of master and worker of the king's moneys and keeper of the exchange within the Tower of London [Map], the realm of England and the town of Calais according to the form of certain indentures, receiving the accustomed fees. By p.s.