Biography of Brian Tuke -1545

Calendars. 22 Sep 1513. Potenze Estere. Inghilterra. Milan Archives. 660. Brian Tuke, Clerk of the Signet, to Richard Pace, Secretary of the Cardinal of England.1

A few days ago saw letters both from him and the cardinal, implying doubts of the king's success. Attribute this in part to the mere lies which he may have heard from the French and their partisans, and partly to the English Cabinet, which omitted to write to the cardinal, though he is of opinion that if he owed so much to any mortal, as our Most Christian king did to God, he should consider that his shoulders were heavily burdened, as all their undertakings had succeeded more prosperously than he could have imagined.

Note 1. Ibid, no. 316.

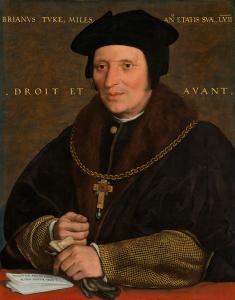

Around 1527 Hans Holbein The Younger (age 30). Portrait of Brian Tuke.

Around 1527 Hans Holbein The Younger (age 30). Portrait of Brian Tuke.

Letters and Papers 1528. 11 Jun 1528. R. O. 4358. Brian Tuke to Thomas Derby (age 19).

Perceived by his letters that my Lord's pleasure is that Lady Margaret's secretaries should be with him on Friday morning. Tuke will be there, but is forbidden to ride, and will therefore go by water. Is to assure Wolsey (age 55) that Stephens' letters did not come in the packet, as the bishop of Bath stated; and therefore Tuke supposed they were either in Mr. Peter's (Vannes') packet, or the same as the letters in Latin to Wolsey (age 55). Doubts not that the Cardinal will find they were not sent in the packet Tuke had. Missed them as soon as he read the bishop of Bath's letters, expecting himself to have heard from Mr. Stephens. This is all he can say. Thinks they have been left out of the packet by inadvertence, or else that my Lord of Bath called Mr. Gregory's Mr. Stephens' letters. The bishop of Bath's packet came whole in a cover from the deputy of Calais, who said they had "flyen over the walls to him at 10 of the clock at night, and should fly over again to the post, to send them over incontinently; and with that packet was a truss in canvas, directed to my Lord's grace, which was not cast over the walls." The letters of sundry dates were put by Twichet into one packet. Sends various letters, and mentions others that came; some directed to the ambassador of Florence, others for Anthony Vivaldi, one to Nich. Carewe. Begs he may come on Friday, as, but for the King and Wolsey's (age 55) commandment, he would not stir from his chamber for £100, "till a thing that is amiss in my body be better amended, for stirring is the most dangerous thing I can do, and besides potions and other medicines I am anointed morning and evening, and have other things administered to me not meet to be used in Court." London, Corpus Christ evening, late.

Letters and Papers 1528. 11 Jun 1528. R. O. St. P. VII. 77. 4355. Gardiner (age 45) to Henry VIII (age 36).

Has at last conduced to the setting forward of Campeggio (age 53), as will appear by the Cardinal's letters sent to Fox. Thinks the King will be satisfied with their services. It is a great heaviness to them to be accused of want of diligence and sincerity. After many altercations and promises made to the Pope, he has consented at last to send the commission by Campeggio (age 53). We urged the Pope to express the matter in special terms, but could not prevail with him in consequence of the difficulty. He said you would understand his meaning by the words, "inventuri sumus aliquam formam." I may be deceived, but I think the Pope means well. If I thought otherwise I would certainly tell the truth, for your Majesty is templum fidei et veritatis unicum in orbe relictum. Your Majesty will now understand how much the words spoken by you to Tuke do prick me. Apologises for his rude writing. Viterbo, 11 June.

Letters and Papers 1528. 21 Jun 1528. Vesp. C. IV. 237. B. M. St. P. I. 293. 4404. Brian Tuke to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (age 55).

According to the purpose he expressed in his last letter to Wolsey, sent to Mr. Treasurer (age 38) to know if he should repair to the King. His messenger found Mr. Treasurer (age 38) sick of the sweat at Waltham [Map], and the King (age 36) removed to Hunsdon [Map], whither he followed him, and delivered him Wolsey's letters to the Bishop of London and Tuke, Tuke's to the Bishop, his answer and Tuke's to the Treasurer. The King asked the messenger what disease Tuke had. The messenger told him wrong; and the King bade Tuke come, though he had to ride in a litter, offering to send him one. Rode thither on his mule at a foot pace, with marvellous pain; for on my faith I void blood per virgam. Arrived yesterday afternoon. The King seemed to be satisfied in the matter of the truce, for which he said he at first sent for him, but now he must put him to other business, saying secretly that it was to write his will, which he has lately reformed.

As to the truce, he said the Spaniards had a great advantage in the liberty to go to Flanders, but the English had not like liberty to repair to Spain; and he also complains that my Lady Margaret is not bound to make restitution for injuries done by Spaniards out of the property of other Spaniards in Flanders. Answered that the liberty to go to Flanders was beneficial to England, which would thus obtain oil and other Spanish merchandise; and, besides, English cloths, which would have been sent to Spain, can now be sent to Flanders. Showed him also the advantage that French or English men-of-war might have, in doing any exploits beyond the French havens; for directly they have returned to safety on this side the Spanish havens, the Spaniards are without remedy, as all hostilities must cease in the seas on this side.

Told him how glad the French ambassadors were when Wolsey, with marvellous policy, brought the secretaries to that point. Assured him "it was tikle medeling with them, seeing how little my Lady Margaret's council esteemed the truce," by which the French were enabled to strengthen themselves in Italy, and their cost in the Low Countries was lost. The King doubted whether the Spaniards would be bound by my Lady Margaret's treaty. Told him she had bound herself that the Emperor should ratify it, and that she would recompence goods taken by Spaniards; adding that if this order had not been taken by Wolsey, the King's subjects passing to Flanders, Iceland, Denmark, Bordeaux, &c. would have been in continual danger of capture. "His highness, not willing to make great replication, said, a little army might have served for keeping of the seas against the Spaniards; and I said, that his army royal, furnished as largely as ever it was, could not save his subjects from many great harms in the length between Spain and Iceland."

The King, being then about to sit down to supper, bid Tuke to rest that night at a gentleman's place near at hand, and return to him this day, when he would speak with him about the other secret matter of his will. "And so, willing to have rewarded me with a dish, if I had not said that I eat no fish," took his leave, and departed two miles to the lodging. On his return this morning, found the King going into the garden, who, after his return, heard three masses, and then called Tuke to the chamber in which he supped apart last night. After speaking of the advantages of this house, and its wholesome air at this time of sickness, the King delivered to him "the book of his said will in many points reformed, wherein his Grace riped me," and appointed Tuke a chamber here, under his privy chamber, bidding him send for his stuff, and go in hand with his business. Expects, therefore, to be here five or six days at least, though he has only a bed that he brought on horseback, ready to lay down anywhere. Must borrow stuff meanwhile, and is disappointed of the physic which he had ordered at his house in Essex, whither he sent a physician to stay with him for a time, promising him a mark a day, horse meat and man's meat. Must bid him return till he has leave to depart, when he begs Wolsey to let him attend on his physician for eight or ten days; "else I shall utterly, for lack of looking to at this begining, destroy myself for ever." The King is expected to remain here eight or ten days. Hunsdon, Sunday, 21 June 1528.

Letters and Papers 1528. 30 Jun 1528. 4440. The young lady (age 27) is still with her father. The King (age 37) keeps moving about for fear of the plague. Many of his people have died of it in three or four hours. of those you know there are only Poowits (deceased), Carey (deceased) and Cotton (age 46) dead; but Feuguillem, the marquis [Dorset] (age 51), my Lord William, Bron (Brown), Careu, Bryan [Tuke], who is now of the Chamber, Nourriz (Norris), Walop, Chesney, Quinston (Kingston), Paget, and those of the Chamber generally, all but one, have been or are attacked. Yesterday some of them were said to be dead. The King (age 37) shuts himself up quite alone. It is the same with Wolsey (age 55). After all, those who are not exposed to the air do not die. Of 40,000 attacked in London, only 2,000 are dead; but if a man only put his hand out of bed during twenty-four hours, it becomes as stiff as a pane of glass.

Letters and Papers 1528. 02 Jul 1528. Titus, B. I. 320. B. M. 4452. John Mordaunt (age 20) To [Wolsey].

Asks him to obtain him the place of under-treasurer, void by the death of Sir William Compton (deceased), about which he spoke to Wolsey at the last vacancy. Last Lent, at Hampton Court, asked him for Sir Harry Wyat's (age 68) room, but he said he had determined to give it to Tuke, though he answered favorably his request to promote him to some such place. Thanks him for all his kindness. Asks his acceptance of 500 marks for the college at Oxford. Will give £100 to the King, if Wolsey pleases, "for his gracious goodness to be showed to me therein."

Asks for the wardship of one of the sisters of the late Mr. Browghton, for his younger sons, as their lands lie in Bradford, in which Mordaunt dwells. Will give £200 more than any other will give. Cannot pay ready money, owing to his expence in buying the heir of Sir Richard Fitzlewes (age 73) and in marrying his daughters, but he will give Wolsey a manor or two instead. Would have attended on Wolsey in person, but dares not presume to do so, in consequence of the sickness. When he first heard the premises, was busy in viewing the King's forest of Rockingham, where the King suffers daily great loss. His servant, the bearer, will attend on Wolsey daily to know his pleasure. 2 July.

Asks him to burn this letter.

Hol., pp. 2.

Letters and Papers 1528. 14 Jul 1528. Titus, B. XI. 356. B. M. 4510. Brian Tuke to Peter Vannes.

much consoled by Vannes' last letters, showing my Lord's great goodness to him.

His wife has "passed the sweat," but is very weak, and is broken out about the mouth and other places. Tuke "puts away the sweat" from himself nightly, though other people think they would kill themselves thereby. Has done this during the last sweat and this, feeling sure that as long as he is not first sick, the sweat is rather provoked by disposition of the time and by keeping men close than by any infection. Thousands have it from fear, who need not else sweat, especially if they observe good diet. When a man is not sick, there is no fear of putting away the sweat, in the beginning, "and before a man's grease be with hot keeping molten." Surely after the grease is heated, it must be more dangerous for a man to take cold than for a horse, which dies in such a case. His belief that the sweat in men who are not sick "proceeds much of men's opinion," is confirmed by the fact that it is prevalent nowhere but in the King's dominion. In France and Flanders it is called the king of England's sickness, and is not thought much of there. It does not go to Gravelines when it is at Calais, though people go from one to the other. It has only been brought from London to other parts by report; for when a whole man comes from London, and talks of the sweat, the same night all the town is full of it, and thus it spreads as the fame runs. It came in this way from Sussex to London, and 1,000 fell ill in a night after the news was spread. "Children also, lacking this opinion, have it not," unless their mothers kill them by keeping them too hot if they see them sweat a little.

Does not deny that there is an infection, which he takes to be "rather a kind of a pestilence than otherwise, and that the moisture of years past hath so altered the nature both of our meats and bodies to moist humours, as disposeth us to sweat." Does not think that every man who sweats is infected, and believes that the disposition to sweat may be, by good governance, relieved. Wishes him to show this to my lord's Grace, to satisfy his mind. Dr. Bartlot, his physician, cannot deny this.

The infection is greatly to be feared and avoided, which cannot be, if men meet together in great companies in infect airs and places.

Wishes him to exhort Wolsey not to run any danger. Was sorry to see by Vannes' letters that he was doing so much with so small assistance. Can do nothing to assist him, now that his house is thus visited, and he himself is in extreme perplexity, and soon cast down by the least transgression of his diet. If he were with Wolsey, would be more likely to bring danger and trouble than do any good. Has not strength to write much or study. Writes this at his waking after midnight, fearing to be still for the sweat, with an aching and troubled head.

Remembering that, as Vannes wrote, Wolsey said that Ireland was in great danger if speedy order were not taken, sends the following news. The prior of Kilmainham, who lies within three miles of Tuke, has been with him twice or thrice. He thinks that the best thing to be done until the King and Wolsey take other order is that some fit man, as James Butler, son of my lord of Ossory, "be subrogate in the lieu of the deputy prisoner," and that raids be made to destroy the corn of the wild Irish, which is the chief punishment of the rebels. The neglect of doing this encourages and enables them to offend the English. He thinks nothing would be necessary but the King's letters to whomever it pleases him to entrust the affair to, and to the Council, to assist and to do anything else beneficial. Will draw up any minutes needed, if Vannes will send instructions, but he does not wish to come to Wolsey, considering the precarious state of his health.

Encloses letters from the deputy of Calais. Portgore, 14 July 1528.

Hol., pp.5. Add. Endd.

On 28 Dec 1538 [his future wife] Grissell Boughton died.

In or before 1540 Brian Tuke and Grissell Boughton were married. They had three sons and three daughters.

In 1545 Brian Tuke died.

Evelyn's Diary. 27 Aug 1678. I took leave of the Duke (age 50), and dined at Mr. Henry Bruncker's (age 51), at the Abbey of Sheene [Map], formerly a monastery of Carthusians, there yet remaining one of their solitary cells with a cross. Within this ample inclosure are several pretty villas and fine gardens of the most excellent fruits, especially Sir William Temple's (lately Ambassador into Holland), and the Lord Lisle's (age 29), son to the Earl of Leicester (age 59), who has divers rare pictures, above all, that of Sir Brian Tuke's, by Holbein.

[his daughter] Elizabeth Tuke Baroness Audley Heighley was born to Brian Tuke.