The Lady of Shalott

The Lady of Shalott is in Tennyson Poems.

In 1833 Alfred Tennyson 1st Baron Tennyson (age 23) published his first version of The Lady of Shalott in twenty stanzas. He later, in 1842, revised it to nineteen stanzas. The following is the ealier version.

The Lady of Shalott Part 1

1.1. On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro' the field the road runs by

To many-tower'd Camelot;

The yellow-leaved waterlily

The green-sheathed daffodilly

Tremble in the water chilly

Round about Shalott.

1.2. Willows whiten, aspens shiver.

The sunbeam showers break and quiver

In the stream that runneth ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four gray walls, and four gray towers

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

1.3. Underneath the bearded barley,

The reaper, reaping late and early,

Hears her ever chanting cheerly,

Like an angel, singing clearly,

O'er the stream of Camelot.

Piling the sheaves in furrows airy,

Beneath the moon, the reaper weary

Listening whispers, ' 'Tis the fairy,

Lady of Shalott.'

1.4. The little isle is all inrail'd

With a rose-fence, and overtrail'd

With roses: by the marge unhail'd

The shallop flitteth silken sail'd,

Skimming down to Camelot.

A pearl garland winds her head:

She leaneth on a velvet bed,

Full royally apparelled,

The Lady of Shalott.

The Lady of Shalott Part 2

2.1. No time hath she to sport and play:

A charmed web she weaves alway.

A curse is on her, if she stay

Her weaving, either night or day,

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be;

Therefore she weaveth steadily,

Therefore no other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

2.2. She lives with little joy or fear.

Over the water, running near,

The sheepbell tinkles in her ear.

Before her hangs a mirror clear,

Reflecting tower'd Camelot.

And as the mazy web she whirls,

She sees the surly village churls,

And the red cloaks of market girls

Pass onward from Shalott.

2.3. Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd lad,

Or long-hair'd page in crimson clad,

Goes by to tower'd Camelot:

And sometimes thro' the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two:

She hath no loyal knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

2.4. But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror's magic sights,

For often thro' the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, came from Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead

Came two young lovers lately wed;

'I am half sick of shadows,' said

The Lady of Shalott.

The Lady of Shalott Part 3

3.1. A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley-sheaves,

The sun came dazzling thro' the leaves,

And flam'd upon the brazen greaves

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A red-cross knight for ever kneel'd

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

3.2. The gemmy bridle glitter'd free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle bells rang merrily

As he rode down from Camelot:

And from his blazon'd baldric slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his armour rung,

Beside remote Shalott.

3.3. All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell'd shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn'd like one burning flame together,

As he rode down from Camelot.

As often thro' the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, trailing light,

Moves over green Shalott.

3.4. His broad clear brow in sunlight glow'd;

On burnish'd hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow'd

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down from Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flash'd into the crystal mirror,

'Tirra lirra, tirra lirra:'

Sang Sir Lancelot.

3.5. She left the web, she left the loom

She made three paces thro' the room

She saw the water-flower bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look'd down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack'd from side to side;

'The curse is come upon me,' cried

The Lady of Shalott.

The Lady of Shalott Part 4

4.1. In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Outside the isle a shallow boat

Beneath a willow lay afloat,

Below the carven stern she wrote,

The Lady of Shalott.

4.2. A cloudwhite crown of pearl she dight,

All raimented in snowy white

That loosely flew (her zone in sight

Clasp'd with one blinding diamond bright)

Her wide eyes fix'd on Camelot,

Though the squally east-wind keenly

Blew, with folded arms serenely

By the water stood the queenly

Lady of Shalott.

4.3. With a steady stony glance-

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Beholding all his own mischance,

Mute, with a glassy countenance-

She look'd down to Camelot.

It was the closing of the day:

She loos'd the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

4.4. As when to sailors while they roam,

By creeks and outfalls far from home,

Rising and dropping with the foam,

From dying swans wild warblings come,

Blown shoreward; so to Camelot

Still as the boathead wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her chanting her deathsong,

The Lady of Shalott.

4.5. A longdrawn carol, mournful, holy,

She chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her eyes were darken'd wholly,

And her smooth face sharpen'd slowly,

Turn'd to tower'd Camelot:

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

4.6. Under tower and balcony,

By garden wall and gallery,

A pale, pale corpse she floated by,

Deadcold, between the houses high,

Dead into tower'd Camelot.

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

To the planked wharfage came:

Below the stern they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

4.7. They cross'd themselves, their stars they blest,

Knight, minstrel, abbot, squire, and guest.

There lay a parchment on her breast,

That puzzled more than all the rest,

The wellfed wits at Camelot.

'The web was woven curiously,

The charm is broken utterly,

Draw near and fear not,-this is I,

The Lady of Shalott.'

In 1842 Alfred Tennyson 1st Baron Tennyson (age 32) re-wrote The Lady of Shalott, changing the last stanza to:

Who is this? and what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they cross'd themselves for fear,

All the knights at Camelot:

But Lancelot mused a little space;

He said, "She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott."

1853. Elizabeth Siddal (age 23). The Lady of Shalott. Part 3 Stanza 5: "Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack'd from side to side".

1853. Elizabeth Siddal (age 23). The Lady of Shalott. Part 3 Stanza 5: "Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack'd from side to side".

Life of William Morris. Within, and yet above or apart from the rest of this group, the two Exeter undergraduates lived in undivided intimacy and unremitting intellectual tension. In the Michaelmas term of 1853 they moved into rooms in college. Morris's (age 19) rooms were in the little quadrangle affectionately known among Exeter men as Hell Quad, with windows overlooking the small but beautiful Fellows' garden, the immense chestnut tree that overspreads Brasenose Lane, and the grey masses of the Bodleian Library. There the long nights set in to crown the long days. On the first night of one of their terms in college, after Burne-Jones (age 20) had arrived late from Birmingham, and had supper, " presently Morris (age 19) came tumbling in," he wrote home next day, " and talked incessantly for the next seven hours or longer." The two read together omnivorously. At first it was chiefly in theology, ecclesiastical history, and ecclesiastical archaeology. Morris early started the habit of reading aloud to Burne-Jones (age 20) — he could not bear to be read aloud to himself — which continued throughout their lives. Among the works thus read through were Neale's ''History of the Eastern Church," Milman's "Latin Christianity," great portions of the " Adla Sanctorum," and of the "Tracts for the Times," Gibbon, Sismondi, and masses of mediaeval chronicles and ecclesiastical Latin poetry. Kenelm Digby's " Mores Catholici " was another book which both read independently; their admiration for it was a thing of which they felt a little ashamed, and which for a time they concealed from each other. Archdeacon Wilberforce's treatises on the Eucharist, Baptism, and the Incarnation, were deeply studied, and Morris was within a little of following Wilberforce's example when he joined the Roman communion in 1854. But alongside of this course of reading, which might be regarded as professional in young men destined for the Church, grew up more and more overpoweringly a wider interest in his- tory, mythology, poetry, and art. Morris arrived at Oxford already familiar with Tennyson and with the two volumes then published of "Modern Painters." One of Burne-Jones (age 20)'s earliest recollections of his first term was of Morris reading aloud "The Lady of Shalott" in the curious half-chanting voice, with immense stress laid on the rhymes, which always remained his method of reading poetry, whether his own or that of others. Ruskin became for both of them a hero and a prophet, and his position was more than ever secured by the appearance of "The Stones of Venice" in 1853. The famous chapter "Of the Nature of Gothic," long afterwards lovingly reprinted by Morris as one of the earliest productions of the Kelmscott Press, was a new gospel and a fixed creed. Curiously enough, in the case of passionate Anglo-Catholics, Kingsley was read much more than Newman, and Carlyle's "Past and Present " stood alongside of "Modern Painters " as inspired and absolute truth. Before Morris had been a year at Oxford the acquiescence of unquestioning faith was being exchanged or a turmoil of new enthusiasms. Burne-Jones (age 20) had come to Oxford already saturated with Shakespeare and Keats, and full of the fascination of the Celtic and Scandinavian mythologies. The Pembroke group, together with the rest of their college, which throughout the Anglo-Catholic revival had remained steadfast to the older Evangelicalism, stood apart from the Tractarian movement, and were full of enthusiasm for modern and secular literature: Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, in poetry ; Carlyle, De Quincey, Thackeray, Dickens, in prose. Thorpe's "Northern Mythology," to which he was introduced by Burne-Jones (age 20), opened to Morris a new world, which in later life became, perhaps, his deepest love, that of the great Scandinavian Epic. His other lifelong passion, that for the thirteenth century in all its works and ways, grew not only on the unremitting study of mediaeval architecture, but on a rapid and prodigious assimilation of mediæval chronicles and romances. But the two books which afterwards stood with him high and apart beyond all others, Chaucer and Malory, were as yet unknown to him ; nor, until it was first brought within their knowledge by the appearance, in 1854, of Ruskin's "Edinburgh Lectures," had either he or Burne-Jones (age 20) heard of the name of Rossetti, or of the existence of that Pre-Raphaelite school from which they received, and to which they imparted, so profound an influence.

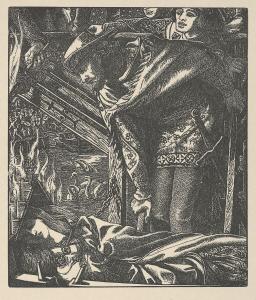

1858. William Maw Egley (age 32). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 3 Stanza 4. After The Lady of Shalott sees Lancelot in the mirror and turns to look at him directly "She saw the helmet and the plume, She look'd down to Camelot." The three candles, of which two are extinguished, signifying the end of life.

1858. William Maw Egley (age 32). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 3 Stanza 4. After The Lady of Shalott sees Lancelot in the mirror and turns to look at him directly "She saw the helmet and the plume, She look'd down to Camelot." The three candles, of which two are extinguished, signifying the end of life.

1862. Walter Crane (age 16). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 4 Stanza 5 in which The Lady of Shalott dies.

1862. Walter Crane (age 16). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 4 Stanza 5 in which The Lady of Shalott dies.

1865. Arthur Hughes (age 32). Study for "The Lady of Shalott".

1865. Arthur Hughes (age 32). Study for "The Lady of Shalott".

1873. Arthur Hughes (age 40). "The Lady of Shalott".

1873. Arthur Hughes (age 40). "The Lady of Shalott".

1875. John Atkinson Grimshaw (age 38). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 4 Stanza 5 in which The Lady of Shalott dies.

1875. John Atkinson Grimshaw (age 38). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 4 Stanza 5 in which The Lady of Shalott dies.

Before 1882. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (age 53). The Lady of Shalott. Part 4 Stanza 7 of the 1842 revised version: "But Lancelot mused a little space; He said, "She has a lovely face; God in his mercy lend her grace, The Lady of Shalott." engraved by the Dalziel Brothers.

Before 1882. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (age 53). The Lady of Shalott. Part 4 Stanza 7 of the 1842 revised version: "But Lancelot mused a little space; He said, "She has a lovely face; God in his mercy lend her grace, The Lady of Shalott." engraved by the Dalziel Brothers.

1888. John William Waterhouse (age 38). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 4 Stanza 3 although not quite consistent with the poem "She loos'd the chain, and down she lay; The broad stream bore her far away,".

1888. John William Waterhouse (age 38). "The The Lady of Shalott". Part 4 Stanza 3 although not quite consistent with the poem "She loos'd the chain, and down she lay; The broad stream bore her far away,".

1895. John William Waterhouse (age 45). "The Lady of Shalott". Part 3 Stanza 5: "Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack'd from side to side".

1895. John William Waterhouse (age 45). "The Lady of Shalott". Part 3 Stanza 5: "Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack'd from side to side".

1905. William Holman Hunt (age 77) assisted by Edward Robert Hughes (age 53). "The Lady of Shalott. Part 3 Stanza 5: "Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack'd from side to side".

1905. William Holman Hunt (age 77) assisted by Edward Robert Hughes (age 53). "The Lady of Shalott. Part 3 Stanza 5: "Out flew the web and floated wide; The mirror crack'd from side to side".

1913. Sidney Harold Metyard (age 45). The Lady of Shalott. Part 2 Stanza 4: "I am half sick of shadows,".

1913. Sidney Harold Metyard (age 45). The Lady of Shalott. Part 2 Stanza 4: "I am half sick of shadows,".

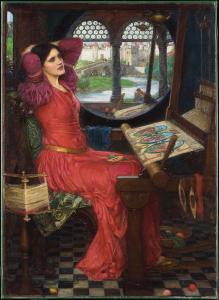

1916. John William Waterhouse (age 66). "I am Half-Sick of Shadows, said the Lady of Shalott". The Lady of Shalott Part 2 Stanza 4.

1916. John William Waterhouse (age 66). "I am Half-Sick of Shadows, said the Lady of Shalott". The Lady of Shalott Part 2 Stanza 4.