Effigy of King Edward III

Effigy of King Edward III is in Monumental Effigies of Great Britain.

SURNAMED of Windsor, was the eldest son of Edward the Second by Isabella of France, and was born at the Castle of Windsor [Map] on the 13th of November, 1312. In a Parliament assembled at York in 1322, he was created Prince of Wales and Duke of Aquitaine. On the formal deposition of his father, he ascended the throne of England on the 25th of January, 1326, being then about fourteen years of age, and was on the 1st of February following girt with the sword of knighthood by his cousin Henry Earl of Lancaster, and crowned at Westminster by Walter Reynolds, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Parliament appointed twelve guardians for the King during his nonage, consisting of five Bishops, two Earls, and five Baronsa.

By consent of these and of the Parliament, Henry Tort-col, Earl of Lancaster, Lincoln, Leicester, and Derby, as Earl of Leicester, Hereditary High Seneschal of England, (son [Note. brother] of the celebrated Thomas Earl of Lancaster, the idol of the people, who was beheaded by Edward the Second,) was appointed guardian of the youthful King. Such were the nominal directors of Edward's Government, while Roger Mortimer, by his close intimacy and influence with the Queen, his mother, was the real. The first act of the first year of his reign was to march against the Scots, who had made an inroad on the borders; in which expedition he was assisted by many Flemings and foreigners, under Sir John de Hainault, brother of William Earl of Hainault, who had aided the Queen and her son against the Spensers in Edward the Second's reign. In this expedition a very remarkable occurrence took place, by which the King's life or liberty was endangered. While the English army lay encamped on the river Weir, Earl Douglas, with two hundred men-at-arms, crossed the stream at some distance above their position. Advancing at a cautious and "stealthy pace," they entered the English camp. At every challenge of the "fixed centinels," Douglas exclaimed, "No ward? Ha! St. George!" as if to chide their negligence. Each soldier on his post thought this to be the reproof of the nightly "rounds" directed to himself, and thus Douglas and his band passed on until he came to the roval tent, into which it is said he entered, and aimed a blow at the sleeping Monarch of England, which was warded off by his Chaplain who was slain by interposing his own body as a shield to his liege lord. The King leaped up, seized his sword, which hung at the head of his couch, the alarm was given, and Douglas made good his retreat, from his bold but abortive enterprize, through the English host, with some loss. Thus nurtured as it were in the din of arms, the master-mind of Edward took a turn towards those military undertakings, which subsequently raised the martial glory of his country to the highest pitch.

Note a. These were, Walter Reynolds, Archbishop of Canterbury, William de Melton, Archbishop of York, John Stratford, Bishop of Winchester, Thomas Cobham, of Worcester, and Adam Orleton, of Hereford, the infamous tool of the Queen and Mortimer. The Earls were, Thomas of Brotherton, the Earl Marshal, Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent, both uncles of the King; the Barons, John Lord of Warren, Thomas of Wales, Henry of Percy, Oliver de Ingham, and John of Ros.

On the termination of this expedition, by the retreat of the enemy within their own frontier, the King returned to London; and shortly after an embassy was sent to his ally, William Earl of Hainault, to demand, on the King's part, one of his daughters in marriage. The Bishop of Coventry and Litchheld, the principal envoy, repairing to the Court of Hainault at Valenciennes, the Earl's five daughters were produced before him, when the Bishop gave his judgment and choice for Philippa, the youngest of them all, being scarcely fourteen years of age. A dispensation for the union of the parties at this early period was granted by the Pope, the bride was conducted to England, and the marriage was solemnized at York [Map] on the 24th February, 1327-8, Edward being then only in his fifteenth year. Charles the Fair, his uncle, King of France, now dying, he claimed the crown in right of his descent from Isabella, his mother; his plea being, that, although the Salic law or custom excluded females from the actual Government, it had no such operation as regarded their male issue. An embassy was forthwith dispatched to France, to interdict the coronation of Philip de Valois, which, however, took place within twelve days after its arrival; and thus subsequently arose the wars of Edward in France in prosecution of this claim.

Until the year 1330, Roger Mortimer, Baron of Wigmore, and now Earl of Marchea, by his influence with the Queen (whose character is further blackened by the imputation of a criminal connection with him), had been the actual Regent of the Realm, while Henry Earl of Lancaster, and the Lords the young King's guardians, were excluded from any real power in administration of state affairs. Mortimer ruled the Queen; and, through the natural induence of a mother on a son of such tender years, employed according to his pleasure the authority of the King himself. By his machinations and the Queen's, Edward had consented to the death of his uncle Edmund Earl of Kent. Mortimer's luxury, cupidity, and pride, had now reached the highest point. On the other hand, the King had attained his eighteenth year, his eyes were opened, and his high spirit determined to govern for itself. The Earl of Lancaster and the offended Barons were not slow to aid this resolution. Mortimer was seized in Nottingham Castle by William Lord Montacute. He and the Queen had thought themselves secure in this stronghold from the attempts of their enemies. The Queen every night caused the keys of the castle to be delivered to her by the Constable, Sir William Eland, and kept them under her pillow; but Lord Montacute went to the Constable, and demanded, by the King's authority, to be secretly admitted within the fortress, for the purpose of seizing on Mortimer. At midnight, therefore, on the 19th of October, Montacute, and the Lords his associates, repaired, under the previous direction of the Governor, to the mouth of a subterraneous passage hewn out in ancient days by the Saxons, which led under the hill, and opened into the donjon, or master tower of the castle. Entrance thus gained, they surprized and seized Mortimer in his chamber, notwithstanding the entreaties of the Queen, who hearing the noise of the confederate band in an adjoining room, guessing their errand, and thinking her son was with them, exclaimed, in the French tongue, "Fair son, spare, spare the gentle Mortimer!" He was removed under a strong guard to the Tower of London, articles of attainder were speedily exhibited against him, confirmed by the Parliament, and he was adjudged to execution. On the 29th of November he suffered death, like a malefactor of the vulgar class, upon the common gallows.

Note a. He was created Earl of Marche in Parliament at Salisbury, in August l328.

In 1337, King Edward having fortified his purposes by alliances with the Earl of Flanders, Jacob Von Artaveldt, the wealthy brewer who ruled the people of Ghent, and the Duke of Bavaria, laid a formal claim to the Crown of France. In the following year he repaired to Cologne to meet the Emperor of Germany, who received him in great pomp, and dispensed with the usual ceremony that Kings should kiss his feet. Two thrones were erected in the open market-place at Cologne; on one was seated the emperor, in his imperial robes, having in his hands the sceptre and the orb of empire, behind him stood a knight, who held over his head a naked sword. He there denounced the King of France as disloyal, treacherous, and unworthy the protection of the Empire, and defied him. He constituted, at the same time, by charter, King Edward his Deputy and Vicar General of the Empire, granting him full power over the territory on this side Cologne. King Edward lost no time in summoning the German feudatories to assemble in Flanders in July of the following year, to open the campaign against the French King by the siege of Cambray.

Thus commenced the first hostilities by Edward the Third in prosecution of his right. Edward soon after formally placed the arms of France, the golden lilies seméea in an azure field, in the dexter quarter of his royal arms, and underneath the motto, "Dieu et mon droit. [God and my right]"

Note a. Charles VI of France, in order to mark a difference between the French and English arms, reduced the number of the lilies to three, but our Henry V defeated the intention doing the same.

In 1341, the claims of John Earl of Montfort and Charles of Blois to the Duchy of Bretagne (the cause of the first being espoused by England and of the latter by France) revived hostilities between the countries. The contest between these two personages was only decided by the death of Charles de Blois at the battle of Auray, in 1364, which gave the Duchy to his rival.

In the year 1344, King Edward held his Round Table at Windsor, encouraging a romantic spirit of chivalry among his nobles, by reducing in some degree to practice the legendary tales of Arthur's Court. In the same policy, as a reward and incentive for gallant deeds, he shortly after instituted the most noble Order of the Garter. In 1346, Philip of France sent his son, the Duke of Normandy, with an army of a hundred thousand men, to invade the Duchy of Guienne. Edward embarked immediately to the relief of his province, with the very disproportionate force of thirty thousand. Baffled by contrary winds from landing in Guienne, he made a descent in Normandy, where Philip, with an overwhelming force, endeavoured to cut off all retreat. He however forced the passage of the Somme at Blanchetaque, and awaiting the army of Philip in a well-chosen spot, at the village of Crecy, on the 26th August, 1346, gave him battle, and totally routed his army, with the loss of 30,000 men, 1,200 knights, the Earl of Alençon, the French King's brother, the King of Bohemia, his ally, and fifteen nobles of the highest rank. The active glory of this victory belonged to the gallant Black Prince.

While the King was absent in France, David King of Scotland, instigated by the intrigues of the French Court, entered England with a powerful army, and laid waste the country with fire and sword as far as Durham. Their progress was arrested by the spirited Queen Philippa, the Archbishop of York, and the Lords Marchers, at Nevill's Cross, about two miles from Durham, where they were totally routed; and David Bruce, their king, taken, and carried to London, where he was confined in the Tower.

In 1356, the Black Prince having made an incursion, with an army not exceeding 12,000 men, into Languedoc, he was pursued on his return by John, who had now succeeded to the Crown of France, who came up with him near Poictiers, and there encountered a signal defeat, with the loss of his liberty. The dreadful thunder storm to which the English army was exposed before Chartres, induced Edward, who thought it was an admonition from Heaven, to check his ambition and grant the French a peace) which was but ill observed.

Enough has been said in this brief way to denote the energy and grandeur of his character as a monarch, and to show what he did in arms for his country. He was equally alive to her commercial interests and to the encouragement of the arts as they were practised in his day. The sun of Edward's glory, however, declined under a cloud. That vanquisher of the invincible, Death, laid the Black Prince low; and the sword of Bertram du Guesclin, Constable of France under Charles V redeemed his country's honour and dominion. Towards the close of Edward's reign, of all the English conquests and possessions in France only Calais remained. The King's character in the decline of life, after the death of Philippa his Queen, who deceased in 1369a, is not exempt from imputation of that frailty which has so often tarnished the silver honours of the aged head. Dame Alice Perers was taken into his highest favour about five years after the above event. She was a woman of exceeding beauty. At a tournament held in Smithheld by the King's command, she rode as "Lady of the Sun" from the Tower of London to Smithfield (the Campus Martius of the City), attended by a procession of knights armed for the jousts, each having his horse led by the bridle by a lady.

Note a. She died at Windsor, on the 15th of August, in the most pious spirit of resignation. Her husband and her youngest son, Thomas of Woodstock, were present at this parting scene, overwhelmed with grief she requested that her debts might be exactly paid, her donations for religious uses fulfilled, and that her body should be buried at Westminster. A sumptuous monument with her effigy was erected for her by her husband in the Abbey there. It is still extant, and is one of those few connected with the English monarchy, which the untimely end of the author of this work prevented him from delineating for his collection.

An interesting description of the King's death-bed is to be found in an old chronicle often referred to by writers of his history. He is therein described as lying on his sick couch (his disease unexpectedly assuming a mortal character), "talking rather of hawking and hunting, and such trifles, than any thing that pertained to his salvation," trusting to the soothing assurances of the Lady Perers that "he should well recover, and not die: who, whilst the King had the use of speech to communicate his pleasure, sat at his bed's head, "much like a dog that waited greedily to take or snatch whatsoever his master would throw from the board." This authority also states, that as soon as she saw the hand of death was on the King, she took the rings from his fingers, and bade him adieu! All his retainers and dependants also "forsook him, and bed." Thus he lay deserted in his extreme hour by all those who had existed on his bounty, except a single priest of the household, "who approached his bed, and boldly exhorted him to lift up his heart in penitence to God, and implore mercy for his sins." The dying King, touched with this simple, honest address, bursting into tears, faintly ejaculated, "Jesu!" the last word God gave him power to pronounce. The priest continued his admonitions that he would show, by such signs as he still might, his repentance, his forgiveness of his enemies, and his trust in God. He replied by deep sighs, by lifting up his eyes and hands to heaven in prayer, by laying his hand on his heart, in token of his forgiveness, from his heart, of all who had offended him. Then taking the crucifix in his hand, with every sign of love and reverence of Him whose subering for his sake it represented, he resigned his spirit to his Creator.

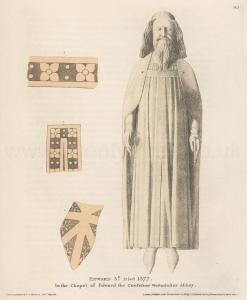

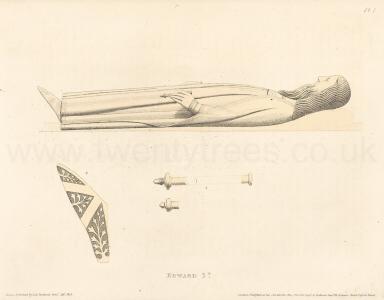

Edward the Third's death took place at his manor of Shene [Map], near Richmond, in Surrey, on the 21st June, 1377, in the sixty-fourth year of his age, he having reigned fifty years and nearly five months. He directed by his last will, dated from that ancient seat of the English Monarchs, Havering-at-the-Bower [Map], in Essex, 25th June, 1377, that he should be interred at Westminster Abbey, among his ancestors of famous memory, but without excessive pomp. With this view, he limited the number of waxen tapers and mortaries that were to be placed during the ceremony about his corpse. He lies on the south side of the Chapel of Edward the Confessor [Map] within a tomb of marble, on which is his effigy of copper, as represented in the plates; it has originally been gilt. His epitaph on the verge of his tomb is thus read by Sandford:

Hic decus Anglorum, flos regum preteritorum. [This is the glory of the English, the flower of the kings of the past.]

Forma futurorum, rex clemens, pax populorum, [The shape of the future, the merciful king, the peace of the peoples,]

Tertius Edwardus, regni complens jubileum, [Edward the Third, completing the jubilee of his reign]

Invictus pardus, bellis pollens Machabeum. [Maccabeus, an unconquered leopard, mighty in war]

Prospere dum vixit, regnum pietate revixit, [While he lived prosperously, he revived the kingdom with piety]

Armipotens rexit; jam celo, Celice Rex, sit. [He reigned mighty in arms; already in heaven, Celice?? King, be]

The effigy of the King is in a grand and simple style. The hair bows over the neck, and he wears the forked beard of the time. The mantle is fastened to his shoulders by a broad band, which extends across the breast. The dalmatic is underneath, gathered in a few broad and beautifully-disposed folds. He has had a sceptre in either hand, denoting his double dominion.

Details. Plate I. 1. Band attaching the mantle to the body. 2. Pattern on the border of the dalmatic. 3. Front view of the ornamented boot. Plate II. Profile. 1. Portions of the sceptres. 2. Side-view of the boot.