Flintshire Historical Society Volume 12

Flintshire Historical Society Volume 12 is in Flintshire Historical Society.

We are met this afternoon to reinaugurate the Flintshire Historical Society. The first inauguration was at a meeting held in this same Chamber on Friday, 13 January 1911. That was almost exactly forty years ago. The years between have been sufficiently long, sufficiently changeful, and sufficiently devastating to make us disposed to seize any threads of continuity that may serve to link the two occasions and bind us to our beginnings. Direct personal links are happily still supplied by a small but lively group of members who were themselves present at that earlier meeting forty years back. It is only indirect links that I can provide, but they are not less real, I hope, for being indirect. At that meeting on 13 January 1911, the most active figures were two. Firstly, there was the Founder of our Society, the late Mr. Henry Taylor, a distinguished antiquary who was for many years Town Clerk of Flint and Deputy-Constable of Flint Castle. Secondly, there was the speaker who delivered the inaugural address, the late Professor T. F. Tout, at that time Professor of History in the University of Manchester, and his address took the form of a notable lecture on the subject ' Flintshire: its History and its Records,' subsequently issued as the first of our Society's publications. Now I had the great good fortune to become a pupil of Professor Tout, and I therefore feel that as a pupil I should today choose a subject that will in some sort link up with the discourse given by my master forty years ago. That is one reason why I have chosen the subject 'The building of Flint': the building of Flint is an essential aspect of the history of Flintshire, for if Flint had not been built, there could have been no county called Flintshire.1 My other reason—and my second link—is this: the person who first made known the real truth about the building of Flint was Mr. Henry Taylor in his valuable book Historic Notices of Flint, published as long ago as 1883. What I shall try to tell you today does no more than follow up the clue that he first supplied—and the supplying of the first clue is often the most important step in any investigation.

Note 1. Even when Flint had been built, the county was very nearly called by another name than 'Flintshire.' The new shire was constituted by the Statute of Wales in March 1284. The relevant clause of the statute lays down that there shall be 'a sheriff of Flint, under whom shall be the cantred of Englefield ' etc. But there is still preserved in the British Museum a document which is written in an unmistakable thirteenth-century official hand, and which is apparently a rough draft of the Statute of Wales, full of the cancellations and interlinings that one usually finds in a draft. There are several very interesting differences between this rough draft and the statute as it was eventually promulgated. And one of the differences is this: that whereas the statute speaks of 'a sheriff of Flint ' the corresponding clause in the draft speaks of 'a sheriff of Rhuddlan.' If the wording of the draft had stood, our county would have been called, not Flintshire, but 'Rhuddlanshire.' See W. H. Waters: A first draft of the statute of Rhuddlan,' in Bull. of Board of Celtic Studes, iv. 345—8.

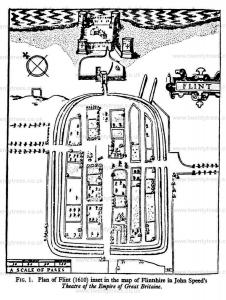

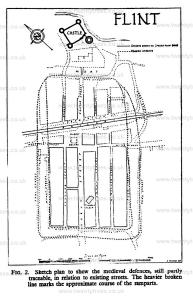

I have said 'the building of Flint' and not 'the building of Flint castle,' for what was built was more than a castle: what was built at Flint was a castle integrated with a fortified town, as was done also at Aberystwyth and Rhuddlan, and later at Conway and Caernarvon—with the difference that at Conway and Caernarvon the town fortifications were more massive than those of Flint and Rhuddlan. At Conway and Caernarvon, as we all know, the town fortifications were strong stone walls which are still there for us to see. At Flint and Rhuddlan, on the other hand, the town fortifications consisted of a palisade of wood and earth protected by a ditch: they have long since disappeared, but we happen to know what the fortifications of Flint looked like, because they still existed in the seventeenth century, and a sketch-plan of them was inset in Speed's map engraved in 1610.2 The area enclosed by them was naturally very much smaller than the built-up area of Flint today3.

Note 2. Speed's plan is reproduced as fig. 1. Edward Lhuyd noted about 1691 that 'Flint is surrounded by a ditch'; Parochialia, i. 86.

Note 3. The circuit of the town fortifications in relation to the present-day streets is shown in the accompanying plan (fig. 2), which I owe to the kindness and skill of Mr. A. J. Taylor and Mr. L. Monroe, to whom I offer most grateful thanks.

Now what was on the site of Flint before Edward I caused his new castle and town to be set there? If we could command some witch of Endor to conjure up for us a view of the site, what would we see? Two things, and probably little else. We would see open fields. We would also see, at the edge of the water of Dee, a low ledge or platform of rock. The historian can tell us something about those fields and that rock. He can tell us that the open fields belonged to an ancient settlement called Radintone or Redinton: this name has long since disappeared, but we find it recorded in Domesday Book in 10864, and it was still current in the district nearly a century after Flint had sprung up to dominate the scene.5 The historian can also produce clear evidence showing that, within a month of the founding of Flint, Edward I was sending out letters dated 'in castro apud le Flynt prope Basingwerk.' It is noteworthy that this form 'le Flynt,' with its definite article, has an exact parallel in Welsh, which has always spoken (and still invariably speaks) of Flint as 'y Fflint,' likewise with the definite article. The parallel suggests that 'the castle at the Flint took its name from something that was called 'The Flint.' If so, this something called The Flint may well have been the ledge of rock on which the castle stands.6 Geologically, of course, that rock is not flintstone but sandstone; but in medieval English the word 'flint' was quite normally used in the general sense of 'rock': thus when the author of Piers the Plowman speaks of Moses in the wilderness causing water to come from the rock, he says that the water sprang out of the flint7. For these reasons historians incline to think that the castle got its name 'Flint' because Edward's men transferred to it the name that was applied in the first instance to the rock on which the castle was built.8

Note 4. J. Tait: 'Flintshire in Domesday Book,' in Flints. Hist. Soc. Publications, xi. 15. For the form 'Redinton' see Cal. Chanc. Rolls, Various, 1277—1326, p. 289, and note 5 below.

Note 5. It is mentioned in the Black Prince's charter of 1361; H. Taylor, Hist. Notices of Flint, p. 42.

Note 6. ' The site chosen (for Flint Castle) was a small rocky platform extending about 50 yards into the channel of the river Dee '; Hist. Mon. Commission, Inventory of the Ancient Monuments, County of Flint, p. 26.

Note 7. Oxford English Dictionary, s.V. ' flint.'

Note 8. J. E. Lloyd, 'Edward I and the county of Flint,' in Flints. Hist. Soc. Publications, vi. 18—22; J. G. Edwards, ' The name of Flint Castle,' in Eng. Hist. Rev., xxix. 315—7.

Such was the site on which the new stronghold was planted. Why was it placed just there, in the fields of Redinton and on the rock that may have been called 'The Flint'? The answer to that question is to be found in the political situation of 1277, when the building of Flint began. At that time, Edward I was committed to a war with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, prince of Wales. It would seem that the king had made up his mind on two points: firstly, that Llywelyn must be compelled to relinquish the lands that he held to the east of the river Conway; and secondly, that thereupon the king must take into his own keeping the coastal region between Conway and Chester, i.e., the two cantreds of Rhos and Tegeingl. To hold this Tegeingl region, which stretched from Chester westwards to the estuary of the Clwyd, Edward evidently planned to have two fortresses. One of them was to be on the north-western limit of Tegeingl, that is, on the important line of the river Clwyd. There, the obvious site was Rhuddlan, whose importance as a strategic point had been realised for at least two centuries: the Normans had built a castle there soon after 1066, and there may well have been an Anglo-Saxon burh there since 921.9 The second of the two fortresses would obviously have to be somewhere between the Clwyd stronghold at Rhuddlan and the traditional English base at Chester. It should be within easy marching distance of either. It should also be in communication by sea with both. This last requirement was important both in peace and in war: in peace, because supplies could be transported much more easily and cheaply by water than by land; in war, because if the castle was besieged and cut off to landward, reinforcements and stores could still he run in by sea. So the new castle must be somewhere on the shore. But the banks of the tidal estuary of the Dee were in general too wet and marshy to provide a good foundation for the heavy masonry of a castle: so some spot would have to be found that was not wet and marshy. A little consideration will show that the site chosen in the fields of Redinton fulfilled all the requirements. It was almost exactly half way between Chester and Rhuddlan. It was within a day's march of either. It was in communication by sea with both. And the ledge of rock—'The Flint,' or whatever it may have been called—provided, beyond all doubt, the solid foundation on which the builders could build: upon it, after seven centuries, the castle still endures.

Note 9. Ibid.

Having seen something of the considerations that determined the building of Flint, we may now turn to the actual carrying out of the work. Our information about this is derived mainly from five accounts of receipts and expenditure drawn up by various royal officers who were in charge of the building operations. As I shall refer a good deal to these five accounts, I had better pause for a moment to explain one or two things about them.

The five accounts are preserved in the Public Record Office, and they are written on parchment and in Latin, as was usual in the Middle Ages. The first of the five accounts10 was made known, as I have already said, by the late Mr. Henry Taylor in his Historic Notices of Flint published in 188311: it was he who gave subsequent investigators the hint that if more of the story was to be recovered, they must look in the Public Record Office. The hint was eventually taken by the late Dr. J. E. Morris, who made known the second12 and third13 of our five accounts in his book, The Welsh Wars of Edward I, published in 1901.14 The fourth account14 (which in some ways is the most important of the five, since it covers a longer period than the others), and the fifth account16 (which unfortunately is a fragment, much of which has rotted away)have both been tracked down since the publication of Dr. Morris's book.

Note 10. Exchequer Accts., Various, 485/19 (cited by Mr. H. Taylor under the older reference, Exch. Q. R. Miscellanea, Army, no. 15/7). This account covers the work at Flint from its beginning in July 1277 to 22 August, 1277.

Note 11. Op. cit., pp. 19—23. Mr. Taylor gives the account in translation.

Note 12. Pipe Roll 124/29. This account covers the period 23 August to 21 November, 1277.

Note 13. Pipe Roll 122/28. This account is for the period 30 November 127 to 5 March 1279.

Note 14. Op. cit., pp. 1

Note 15. Pipe Roll 131/26. account is for the period 5 March 1279 to 11 November 1284.

Note 16. Chancery Miscellanea, 2/2/17.

Expenditure on buildings, in the thirteenth century as now, fell under three main heads: wages of workmen; cost of materials; cost of transport. Of these, much the largest and, for our purposes, much the most interesting was wages of workmen. It is important to notice at the outset, however, that our five accounts supply very varying amounts of detail under the head of wages. Some of them, as for instance the first and the fifth, give very full details, stating not only the sums spent in wages, but also the exact periods covered, the precise numbers of workmen employed and the particular rates of pay. At the opposite extreme some accounts, as for instance the fourth of our series, simply set down the total lump sums paid to the various categories of workmen—masons, carpenters and so on—without stating the numbers that were paid, or the precise periods for which they drew pay, or the varying rates of pay that they received. Because of these variations in the form of the accounts, we can reconstruct the story of the building at Flint only with varying clearness and in considerably less detail at some stages than at others.

There is another consideration that must also be borne in mind when using these accounts as a means of conjuring up a view of the past. We must remember that they originated as purely business documents, and that the officials who compiled them had no thought of our using them today, nearly seven centuries later, as materials of history, as historical evidence. Consequently, though these accounts tell us a great deal about some things, they often tell us little or nothing about other things that would interest us greatly. For instance, they frequently tell us that at certain specified times such and such masons or carpenters were at work; but usually they do not specify what exactly those masons or carpenters were doing: for the practical purposes of the account, all that mattered was that the men were on the spot, doing whatever they might be commanded to do. Occasionally, indeed, the accounts do mention some piece of work specifically, but that is the exception rather than the rule. As historical evidence, therefore, our accounts have many limitations, but they can still tell us a good deal if we care to examine them with attention and patience. And in doing so, we must keep in mind one point that is of general application to the process of medieval building. There is abundant evidence that medieval building work, especially in stone, was mostly carried out in what was called the season,' which was reckoned as the part of the year extending from about April to about November. The months from about November to about April were a slack time during which the workmen employed on a building job might fall to as little as one- seventh of the numbers employed on that job during the season. In the Middle Ages, therefore, the building that was done during the course of any twelve-month was in fact done mainly in the seven months or so from April to November.17

Note 17. Proc. of British Academy, xxxii. 18—19.

Through the medium of our five accounts it is possible to discern that the building of the castle and town of Flint passed through three successive stages:—

(i) In the first stage, the work was pressed forward at speed. The object presumably was to establish a strong defensive position without delay.

(ii). In the second stage, the pace of construction was considerably slackened. The explanation is evidently to be found in the fact that much more labour was at this stage being concentrated upon the building of Rhuddlan, presumably because its more forward geographical position gave it priority in military importance.

(iii). In the third stage, the main effort was transferred back to Flint, and the work there was much accelerated; at Rhuddlan, on the other hand, activity was markedly curtailed.

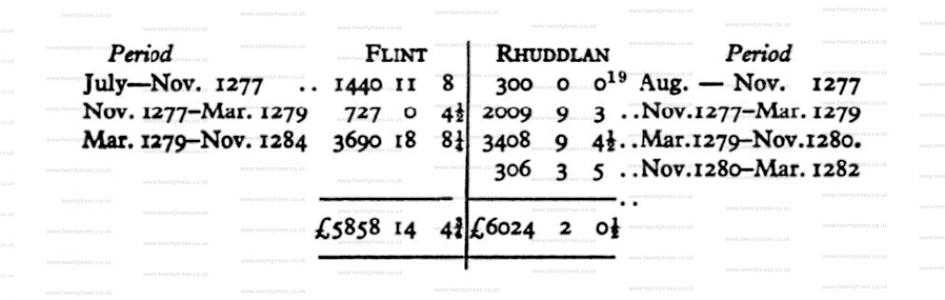

The validity of these inferences is broadly demonstrated by a tabulated comparison of the successive wages-bills at the two fortresses.18

Note 18. The recorded expenditure on the two castles is summarised in tables, ibid., pp. 68—9. The figures given here for Rhuddlan leave out a total of £755 5s 3d., wages incurred in improving the course of the river Clwyd, a piece of work specially undertaken in order that ships might be able to sail easily up to the castle. (This illustrates, incidentally, the importance that Edward I attached to good communications by water for his castles). There was no comparable item of expenditure at Flint, where the castle was right on the estuary of the Dee, which furnished an unimpeded navigation.

Note 19. This is an estimated figure.

It is unfortunate that the accounting periods for the two jobs do not happen to coincide after March 1279, but certain points are nevertheless quite obvious. One is that the wages at Flint for the sixteen months Nov. 1277—March 1279 were only half of what they had been for the four months July—November 1277. A second noteworthy fact is the marked disparity between the £727 wages at Flint and the £2009 at Rhuddlan in the period November 1277 — March 1279. Lastly, there is the very clear indication that the bulk of the work at Rhuddlan had been achieved by November 1280, i.e., by the end of the building 'season' of that year. We shall see later that in March 1281, i.e. precisely at the beginning of the very next 'season,' there came a notable acceleration of the work at Flint. So the three stages in the operations at Flint seem clear—all the clearer because they also appear to interlock with those at Rhuddlan.

The First Stage

It is usual to say that the building of Flint 'began on Sunday, 25 July 1277'. That statement rests on the fact that the first of our five Flint accounts records the first pay-day at Flint as occurring on that date, when specified numbers of workmen drew wages in advance up to the following Saturday, 31 July. But the preceding entry in the same account shows that most of these same workmen had had a previous pay-day on 18 July, when they had drawn wages in advance up to 24 July, i.e. the day before their first pay-day at Flint. That previous pay-day on 18 July took place, the account says, at Chester. Now the workmen numbered hundreds, and the king would naturally not wish to pay them wages for kicking their heels in Chester; so we may probably assume that they would move on from Chester very soon after that pay-day on 18 July. They need not have taken long over the journey from Chester to the site of the new fortress. It is therefore not at all unlikely that they had already been working at Flint for a short while when their first pay-day occurred there on Sunday 25 July 1277. So the birthday of Flint, the day when the first sod was cut for the foundations, was probably not on Sunday, 25 July: it may well have been a little earlier, say about 21 July. It is the weeks from that date to the end of the season of 1277 that form the first of the three stages in the building of Flint.

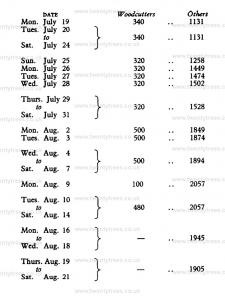

In the first stage the work was going forward at speed. What did at speed mean when expressed in terms of labour? This question can be answered fairly precisely, because the first of our Flint accounts happens to specify, not only the sums of money spent in wages, but also the numbers of workmen and the exact periods for which they received pay. For the period covered by our first account we can therefore tabulate the numbers of the various workmen day by day. They add up as follows, but it is convenient, for reasons that will appear, to keep the numbers of woodcutters apart.20

Note 20. The first of our five Flint accounts forms a part of Exch. Acct. Various 485/19, which is described in the contemporary endorsement as a "roil of the wages of carpenters masons smiths diggers and other workmen who were in the king's army at Flint and Rhuddlan in the time of the Welsh war in the fifth year of King Edward, and paid by Master Thomas Beck then keeper of the wardrobe of the aforesaid king." The entries are grouped into 15 paragraphs followed by a final paragraph of miscellaneous wages, and the expenditure recorded in each paragraph is totalled into a summa at the end of the paragraph. Against each of the paragraphs except the last there is entered in the margin the place where the payments in that paragraph were made. The first paragraphs record the payments down to Saturday 21 August: against paragraph 1 the marginal place-name is Chester, and against paragraphs 2 to 5 inclusive it is Flint. Paragraphs 6 to 15 record the payments from 22 August to 15 November, and against these paragraphs the marginal place-names are Degannwy and Rhuddlan. This arrangement of the entries seems to imply that the payments down to Saturday 21 August were, after the initial pay-day at Chester, made at Flint and for Flint. That supposition is strengthened by a further consideration: that the second of our Flint accounts, rendered by William de Perron as keeper of works, begins two days later on Monday 23 August. This suggests that responsibility for payments at and for Flint was transferred from the keeper of the wardrobe to William de Perton as from 23 August.

The numbers of woodcutters have been stated apart because those workmen were probably not directly concerned in the work of building: they were almost certainly employed in clearing passes through the woods—a marked feature of Edward I's policy in Wales both in 1277 and later in 128421 — and it is noteworthy that they disappear from the account after 14 August. The really significant figures are the totals of the other workmen. These, it will be observed, rose steadily from 1131 in the first week to 2057 in the fourth, and in spite of a decline in the fifth week, the number then employed still stood definitely higher than in the first week. Now although we cannot assert positively that every man-Jack of these workmen was engaged in one way or another upon the building of Flint, it seems reasonable to assume that the great majority were. If so, these totals supply useful notional figures of the labour force employed upon the building of Flint down to Saturday, 21 August 1277. That date is a convenient point at which we may pause for a moment and take stock of what is happening.

Note 21. Cal. Chancery Rolls, Various, 1277—1326, pp. 168, 171, 173, 184, 232, 254; J. E. Morris, Welsh Wars of Ed. I, p. 130.

The first thing that must strike any observer is the transformation of the scene. In a matter of days, those ancient fields of Redinton and that timeless rock at the water's edge have exchanged their native quiet for the busy hum of men. Builders are come, not merely by the dozen or by the score, but by the hundred and even by the thousand. Their numbers become impressive if we remember that they are not local men recruited on the spot. They have been brought from England. Indeed, our first Flint account occasionally says where they have come from. It tells, for instance, that among the 1131 workmen at the first pay-day on 18 July there were 280 from Cheshire, 180 from Shropshire, 80 from Lancashire, 60 from Staffordshire, all diggers, and 300 carpenters from Derbyshire. A little later, it mentions that the workmen drawing pay at Flint on 9 and 16 August include a gang of 300 diggers from Hoyland in the West Riding. And there is other evidence indicating that Edward I's workmen on his Welsh castles come from places a good deal farther afield in England even than Yorkshire and Derbyshire. We readily remember that they cannot have come by train or bus. But the lack of transport is by no means the only difficulty. We may easily forget that the England from which Edward I has to recruit them is not a populous land; and that this Flint of ours is not the only new fortress that he is building in this summer of 1277. Already since the beginning of May he has been putting up a new castle at Builth in mid-Wales, and the wages spent on that work indicate that the workmen employed there may average about 200. And again, within a week of starting operations at Flint, Edward has also begun to build another very similar fortress at Aberystwyth, and the wages there expended suggest an average of some 350 men for that work.22 When all these various considerations are taken into account, the amount of labour that Edward has assembled at Flint in July and August 1277 is impressively large.

Note 22. For the wages at Builth and Aberystwyth see Proc. Brit. Academy, 66—7; and for the estimating of numbers, see ibid., pp. 73—9.

Now what were all these workmen doing during those first five weeks? To that sort of question the accounts, as I have already remarked, supply but a dusty answer. The first of our Flint accounts does however indicate at least two general conclusions fairly clearly.

(1) If we observe the proportions between the various kinds of workmen employed at Flint in the five weeks ending 21 August and compare them with the proportions between the same kinds of workmen in the first season of the building of Beaumaris a few years later, we shall find a rather striking contrast. The three kinds of workmen that are of special interest in this comparison are the masons, the carpenters, and the diggers. At Beaumaris the proportion was 400 masons to 30 carpenters to 2000 diggers: i.e., 13 masons to I carpenter and I carpenter to 66 diggers.23 At Flint, on the other hand, the proportions during the first five weeks were (on an average) 90 masons to 291 carpenters to 1304 diggers: i.e., I mason to 3 carpenters and I carpenter to 4 diggers. Therefore, while at Beaumaris the biggest contribution to the work would be made by masons and diggers, at Flint in the first five weeks the biggest contribution would be by carpenters and diggers. In other words, while at Beaumaris building in stone would be relatively the more important outcome, at Flint during the first five weeks building in stone would be relatively the less important outcome. What does that suggest? Let us make yet another comparison. When, six years later than Flint, Edward began to build Conway and Caernarvon, we know that at both places he got to work at once, not only on the castle but also on the town fortifications as well.24 We may reasonably assume that he would do the same at Flint. Again, when Edward built Rhuddlan we know that he put up houses in the town.25 It is reasonable to suppose that he would do likewise at Flint also. The new town of Flint was set in the midst of the bare open fields of Redinton: it therefore needed to have houses for habitation as well as fortifications for defence if settlers were to be attracted—and it was Edward's policy that they should be attracted. Now medieval houses were usually made of timber, and the town fortifications of Flint consisted of a palisade and ditch. So the workmen for building such houses and such a fortification would be precisely the carpenters and the diggers. It therefore seems a reasonable deduction that the large number of diggers coupled with the high proportion of carpenters employed at Flint from the very start, implies that work on the fortification of the town and the building of houses was being taken in hand from the start alongside the work on the castle itself.

(2) The second general conclusion is that the presence of a modest proportion of masons implies that at least some building in stone was under way.26 As the town fortifications of Flint were not of stone, we may safely surmise that any stonework put up would be some part of the castle. But in our first account there is no clue to the precise nature of the stonework that was being erected during these first five weeks.

Note 23. Ibid., p. 55. The numbers are as estimated by the clerk of the works in February 1296. He estimated 30 for the smiths as well as for the carpenters, but the account for the 'season' of 1295 quite clearly that the carpenters had in fact been twice as numerous as the smiths: in that the proportion would be something like 400 masons to (say) 60 carpenters to 2000 diggers, i.e. about 6 masons to 1 carpenter to 30 diggers. Even so, however, the broad contrast with the Flint proportions would still stand.

Note 24. Ibid, pp. 40—42.

Note 25. Ibid., p. 32.

Note 26. In the first Flint account (i.e., down to 21 August) masons appear only as follows: 201 from Saturday 17 July to Saturday 3 r July, when they disappear from the account; and 51 from Monday 10 August to Saturday 21 August, when they drop out again. These vicissitudes are hard to understand, but statistically the number give a daily average over the five weeks of some 91 masons.

On 23 August begins the second of our five Flint accounts, and this takes the story to the end of the 'season' of 1277, i.e. to the end of what I have called the first stage of the building. This second account is in one important respect less helpful than the first: unlike the first, it does not record the exact daily number of workmen who were paid, but merely the overall totals of workmen who received pay at any time between the beginning and end of the period covered by the account. Consequently, we can no longer state the precise daily numbers of workmen but only the average daily numbers. This second account is divided into two parts, firstly, 23 August to 10 October, and secondly, from 10 October to 21 November.

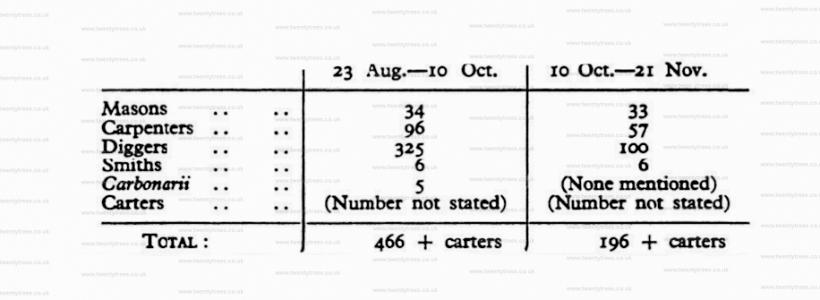

We have seen that on 21 August the total number of workmen was 1905. For the seven weeks from 23 August to 10 October the average daily total of workmen at Flint was about 470, in which the proportions were 34 masons to 96 carpenters to 325 diggers: i.e., I mason to 3 carpenters and I carpenter to 3 diggers. For the succeeding six weeks from 10 October to 21 November the average daily total was about 200, in which the proportions were 33 masons to 57 carpenters to 100 diggers, i.e., I mason to nearly 2 carpenters and I carpenter to nearly 2 diggers.27 Each of the two periods shows a decline from the numbers employed during the period preceding. The fall in the second period is not, of course, surprising, as it was usual for the numbers of workmen to taper off as the 'season' approached its end. In the first period, the most striking drop from the 1905 of 21 August to the average 470 of 23 August onwards was presumably due mainly to the fact that the new work on Rhuddlan castle and town was absorbing a larger share of the available labour. It is also noticeable that, over the 13 weeks from 23 August to 21 November, the average numbers of masons remained steady at 33 and 34, while there was a drop from 96 to 57 in the averages of carpenters. Even so, however, the carpenters still outnumbered the masons by two to one. So we may perhaps infer that although the work at Flint had been slackened since 23 August, it was being applied very much as before, partly to the town's fortifications and to houses, and partly to stonework in the castle, though our second account still does not say what exactly that stonework was.

Note 27. For both periods the account states the number of each class of workmen and the total wages paid to each class, but for the masons, carpenters and diggers it also states the individual rates of pay: e.g. 'To 88 masons, of whom 1 took 8d. a day and the remaining masons each of them 4d. a day for their wages during the aforesaid time (i.e. Monday 23 August to Sunday 10 October), £28. 5s. 4d' A little simple arithmetic shows that the specified numbers of masons, carpenters and diggers were not all working during the whole of the specified period. In the case quoted, if all the 88 masons had been paid for the whole 49 days, the total would have been £72 13s 8d. But the total actually paid to them was £28 5s 4d. Over the whole 40 days therefore the average number of masons employed was: 28.25/72.65 of 88, which in round numbers would be 34. (It seems reasonable to assume that they were paid for 7 days in each week, because the workmen contemporaneously at Rhuddlan were certainly so paid: this is clear from Exch. Accts. Various, 485/19). If we apply similar calculations to the numbers of carpenters and diggers, the average number at work daily throughout the two periods were as follows:

The Second Stage

We now come to the third of our five accounts, which covers the period 30 November 1277 to 5 March 1279, a period of 15 months, including the whole building 'season' of 1278. How much the pace of the work at Flint had slowed is evident from this simple comparison: that the wages paid during these 15 months amounted to no more than £727 4s. ½d., whereas in the preceding 13 weeks they had been £440 11S. 8d., Two other points also stand out in this third account. Firstly, the only wages paid to masons were for dressing stone in a quarry at Nesshead.'28 This seems to mean that no masons were working on the actual site of Flint during these fifteen months, and if that was so, we seem to be left with the rather unexpected deduction that no masonry was erected at Flint between November 1277 and March 1279. Secondly, this account records the paying of wages to a plumber for putting lead roofing on ' towers in the castle.'29 The account simply says 'towers' in the plural; it does not say how many or which towers were roofed: but as the plural is used, there were presumably at least two, and there would not in any case be more than four. The amount of wages paid to the plumber suggests the minimum rather than the maximum number. But the important point is this. Towers would not be roofed with lead until they had been built to their full height. But if we are justified in the previous inference that no masonry was erected at Flint between November 1277 and March 1279, any towers that were roofed during that period had presumably been built to their full height before November 1277. If so, then we have a clue to what the masons employed between July and November 1277 had been doing: they had probably been employed largely upon the towers of the castlc, and they had apparently completed the masonry of at least two of them.

Note 28. Presumably near the little village of Ness in the Wirral, right opposite Flint; and therefore the stone could be brought across by boat. The account states that this particular lot of stone was 'for paving (which presumably means 'revetting') the ditch around the castle of Flint,' but goes on to remark that the ditch was not however paved with this stone in the time of the aforesaid Nicholas (i.e. Nicholas Bonel, the clerk of the works who rendered the account for the period 30 November 12 to 5 March 1279), but turves.' Dr. E. Neaverson already suggested, on purely geological grounds, that some of the stone in the castle 'resembles the Middle Bunter sandstone of Wirral and Chester' (Medieval Castles in North Wales, p. 41): we may now add the quarry or at any rate one the quarrie, was near Ness.

Note 29. Et in stipendiis cuiusdam plumbarii cooperientis turres (sic in full) in estro predicto per predictum tempus 24s.'

We turn next to the fourth of our Flint accounts, which covers the period March 1279 to November 1284, with a few further payments scattered between June 1284 and December 1286. Unfortunately this account is very inconveniently arranged for the purposes of the historian: it records the sums expended in wages as lump totals for periods of three or four or even five years, whereas what the historian needs is an account setting out the expenditure for a year or so at a time, so that he can form an impression of the ebb and flow of the work. In the particular case of Flint what the historian would wish to know is this: as the work there had evidently slowed down after November 1277, when did it start to quicken again? The fourth of our Flint accounts does not enable us to judge. Luckily, however, the fifth account comes opportunely to our aid.

This fifth account is only a fragment. It originally consisted of several sheets of parchment stitched together in the usual way to form a roll, but by now only the first sheet survives and parts even of this have been so badly damaged that some of the entries are illegible: those that can be read, however, are very informative.

The heading describes the roll as an account of wages 'paid to masons working at Flint.' The payments begin as from 9 April 1279, and the account records the numbers of masons who drew pays firstly between 9 April 1279 and 29 October 1279, and secondly between 7 October 1280 and 11 May 1281, at which point the parchment has broken off.

The entries in the year 1279 show that from 24 July to 30 September the masons at Flint amounted to an average of rather more than 20, but by the end of October their number had dwindled to vanishing point. Between 9 April and 24 July the entries are not fully legible, but the number of masons employed in those weeks was clearly much below the 20 who were at work from July to September. The account does not specify what these masons were all doing in 1279, beyond noting that a payment made about 13 July was for taskwork in making 7 perches 8 feet of wall in the castle ditch. But the presence of masons at all, even to the modest number of 20, presumably means that at least some masonry was being erected between the middle of July and the end of October 1279. On the other hand, since the payments recorded in the account jump straight from 29 October 1279 to 7 October 1280, we must presumably infer that no masons were working at Flint between those dates.

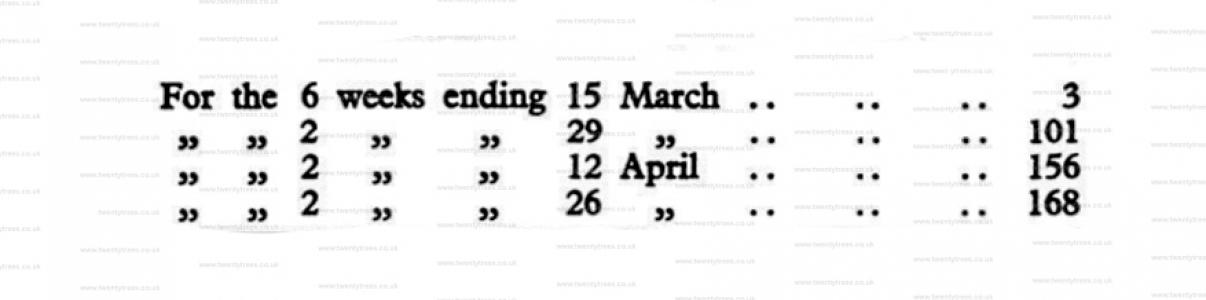

When, however, we come to the series of payments from 7 October 1280 onwards, we observe a significant change. The masons working between 7 October and 14 December 1280 average only about five, but they were employed, the account says, in making a new lime-kiln which was additional to and evidently larger than the existing kiln, for the latter is referred to as the smaller kiln.'30 During the slack period preceding the ' season of 1280, therefore, they were building an additional and larger lime-kiln at Flint. So evidently they expected to be burning more lime. Why? Presumably because they expected to be needing more lime in order to mix greater quantities of mortar. In other words, they were planning to erect more mason" in the coming 'season ' of 1281 than in the preceding seasons.' Now we have already seen that the masons at Flint had averaged about 20 in the latter half of the season of 1279 and about 35 in the latter part of the ' season ' of 1277. Here are the numbers of masons employed at Flint in 128131:—

Note 30. The first in October 1280 records the payment of wages 'duobus cementariis incipientibus unam fornacem ad calcan coquadam,' and this work contintued until 15 December. One of the payments made on 1 Decamber, however, was to David Dew 'pro factura et combustione unius alcis ad fornace minore.' So the 'smaller kiln' is evidenly in use burning lime while the 'new kiln' was still under construction.

Note 31. The accounts state in detail, not only the numbers of workmen but also the individual rates of pay and the number of days they all worked. As all the workmen did not work the full number of days - 12 for the fortnights ending 29 March and 12 April, and 11 for the fortnight ending 26 April - it would obviously be misleading to count all the individual workmen who drew pay during ach fortnight: for purposes, the allowance must be made for the varying number of days that they worked. Such allowances have bccn madc in this table: thus in the ending 26 April, the number of indvidual workmen who drew pay was 193, and in the preceding fortnights it was respectively 166 and 103.

At that point the account stops short because the rest of the parchment has broken off. But the significance of those surviving figures is unmistakable. When the account reaches the middle of March—when, in other words, it reaches the opening of the 'season' of 1281—it shows the number of masons just shooting upwards. No pressure-gauge could be clearer. The work is evidently going forward again at speed: its third stage is begun.

The Third Stage

Although our fragmentary fifth account breaks off at the end of April 1281, its evidence that considerable numbers of masons were working at Flint from the very beginning of the 'season' of 1281 may probably be taken as a good indication that those numbers would be pretty well maintained throughout that 'season.'32 If they were, then we may suppose that the year 1281 saw the erection of a substantial amount of masonry in Flint castle. But what exactly that masonry was, and how much still remained to be done at the end of 1281, we cannot tell. We know from our fourth account, however, that workmen were employed upon the castle and the town till 1284, and some even till 1286. Part of their labour may well have been devoted to rounding off whatever had still remained undone at the end of 1281. But we must not overlook a further possibility. In March 1282 a serious rising broke out in Wales. We know that Flint was one of the first places to be attacked, and the rebels probably did a good deal of damage there. So the expenditure at Flint after 1281 may well have been devoted in part to the repair of such war-damage. However that may be, the indications are that the building of Flint, including the repair of its war damage, was substantially achieved by 1284. The enterprise was thus accomplished within a space of seven years. And it cost, in round figures, some 0000, which was a large sum in the circumstances of those days.

Note 32. This was certainly the case at Harlech in 1286; Proc. Brit. Acdemy, xxxii. 74; and the seems to be true at Builth in 1278 Arch. 486/22) and in 1280 (ibid., 485/23).

My tale is now told. Perhaps you have been wondering why I have not told it as a straightforward story, without interrupting its sequence to dilate upon those five accounts or to trouble you with statistics and the like—in other words, why I have not told you the conclusions without dragging you through the processes by which the conclusions are reached. To have just handed out the conclusions without the hows and whys would doubtless have been simpler for me and much less exacting for you. I have deliberately chosen the harder and more roundabout way for two reasons.

In the first place, I did not want to present you with conclusions cut and dried. I wanted you, if you would, to assist at distilling the conclusions from the sort of raw material that historians use. So we had to go through the process of distillation step by step, and observe the hows and whys.

In the second place, those five accounts that I have troubled you withal are just a few samples out of the great massof Flintshire historical material waiting to be distilled. There are great quantities of this Flintshire material in the Public Record Office alone, as several of the publications of our Society have already indicated. There are also quite large accumulations of it in the National Library of Wales, and some specimens cf these have likewise been published by our Society. And now in these latter days, thanks to the initiative of our Clerk of the Peace, Mr. W. Hugh Jones, we are likely to have in Flintshire an institution which is being set up by all enlightened local authorities, that is, a local Records Office, which will not only see to the proper preservation of the official records of the county, and of any other Flintshire archives, public or private, that may be deposited by their owners, but will also make them all available for study by those who are interested in Flintshire history.

Everything considered, Flintshire is one of the richest of Welsh counties in the extant materials of its own history. Our Society exists in order to encourage the publication and study of Flintshire's historical material, so that we Flintshire folk may better know the history that concerns us most nearly, the history of our own shire. Some of that history, as I have tried to show this afternoon by a concrete example, can often be discovered in quite surprising detail. Of course, we may not all be particularly attracted by medieval castles, but there are plenty of other subjects available. The history of Flintshire is sufficiently varied to appeal to most of us at some point or other. At one point it touches us all alike: for in all its variety, it is the story of the inheritance in which we Flintshire folk are partakers together.