Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society Volume 8 Pages 35-62

Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society Volume 8 Pages 35-62 is in Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society Volume 8.

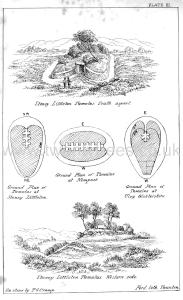

Remarks on ancient chambered tumuli as illustrative still existing at Stoney Littleton [Map], near Wellow, in the county of Somerset. By The Rev. H. M. Scarth (age 44), M.A.

Among the most curious remains of ancient time, and undoubtedly the most ancient, are the Tumuli which still exist in many parts of this country, especially in Wilts, Somerset, the Sussex Downs, Yorkshire, and elsewhere. These are, however, fast disappearing, as cultivation is extending itself; and have in past ages been treated with little respect, and often rifled for the sake of supposed treasures. To the historian of ancient Wilts, and to more recent writers, we are indebted for much information on this curious subject; and to the published engravings in Sir R. C. Hoare’s valuable work we owe exact ideas of the relics found in the barrows of the Wiltshire Downs; while the unrivalled collection of sepulchral remains at Stourhead give to the antiquary an opportunity of comparing the interments of different periods, and drawing from thence inferences which become of great importance in tracing historical epochs, which comparisons are the only guide we have in dealing with pre-historic times.

This paper, however, does not profess to treat of the remains found in ancient tumuli, but rather of the tumuli themselves, and more particularly the tumuli which contain chambers, nearly all of which have disappeared; but happily one perfect one remains, that at Wellow, in Somerset. Others formerly existed in the county, the record of one of which is still preserved, although the tumulus has itself be- come a confused heap of stones. Before, however, entering upon any detailed account of the chambered tumulus at Wellow, it may be well to say a word or two on ancient modes of interment in sepulchral barrows.

Happily, through the careful investigations of archaeologists in different countries, our knowledge of this subject is becoming pretty exact, as well as extensive. To Mr. Lukis (age 70) we are indebted for active and careful investigations in the Channel Islands, especially in the island of Guernsey, where he has brought to light much that may greatly assist us in forming just conclusions respecting other places where similarly constructed barrows have been discovered. So much mystery has hitherto hung over the stone chamber, and the ancient mound of earth which occasionally covers it, that much is due to those who have given to the world correct information as to the purposes for which they were designed. Mr. Lukis (age 70), with much labour, explored forty of these ancient sepulchral remains in the Channel Islands, and some in France and England, and says: I have found a very remarkable similarity pervading all, as though a definite architectural law had regulated their construction, and a precise plan had determined the mode of interment.... From numerous accounts which have reached us, we have reason to conclude that the same structures are to be found in most parts of the world." This being the testimony of a very careful investigator, we shall go on to see to what class of tumuli, and to what people, the curious sepulchre at Wellow may be referred.

It would be needless for me here to go into a classification of sepulchral remains, which has already been done so ably by Mr. Lukis in his paper in the Archæologia, Vol. XXXV., p. 232. To that I would refer the curious enquirer into these and such like monuments. He there states that "Cromlechs, cists, cycloliths, peristaliths, etc., exist in Asia, Africa, North America, and indicate that the cromlech-building people were branches of one original stock that they took with them the same ideas in their migrations, and preserved the same customs as those whom we designate the Celtas; and we find, further, that their modes of interment were in every respect identical." And here I would refer to a work of peculiar interest, entitled "The Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley," by E. G. Squire and E. H. Davis—a work of great research and very carefully executed, with plans and drawings. It is there asserted that earth-works are found along the whole basin of the Mississippi and its tributaries; also in the fertile plains along the Gulf of Mexico. Abundance of small mounds are found in the Oregon territory. These remains are not dispersed equally over the areas of the countries mentioned, but are mainly confined to the valleys of rivers and large streams, and seldom occur far from them.

If so much interest attaches to these remains, how necessary it is to preserve and carefully to record whatever monuments still exist in this island of the ancient people who constructed these works, because such monuments become to us a means of tracing the spread of a particular race over the surface of the earth, and give us a clue to their degree of civilization, and in a certain extent to their habits; and serve to shew the connection between various races which have succeeded each other.

It; seems that the most-primitive form of Celtic grave which we find is the simple trench, of three or four feet in length by two in width, and a few inches deep, with occasionally a rude floor of flat stones or pebbles, on which the remains were laid, and covered with a layer of light clay, or, as invariably occurs in the Channel Islands, according to Mr. Lukis’ statement, "a layer of three or four inches in thickness of limpet-shells only, the whole being concealed with a large rude block of granite. Coarse pottery, clay and stone beads, flint arrow-points, and a few flakes, generally accompany the remains." Next to these may be classed cists, which are small enclosures formed of erect or recumbent stones placed in contact, and covered by one, or rarely two, large flat stones. These have been found attached to the sides of cromlechs, or grouped together, or detached. The mode of interment was by first removing the cap-stone and lowering the contents into the interior; and we have an instance of this kind recorded by Mr. Skinner, in a barrow which he opened in this county, to which I shall hereafter allude. Successive layers occur in these, which are separated byflat stones; two or three layers may be found in one cist, the cap-stone being replaced after each interment. In Guernsey, Mr. Lukis states that complete skeletons have been taken from the cists, and also stone celts, retaining the most beautiful polish. His idea is, that in process of time "a bank of earth came to be heaped up against the supports outwardly, as a means of protection, to within a few inches of the under surface of the cap-stone."

"This earthwork," says he, "is the first indication of those lofty tumuli which were raised by politer nations of the world, and of the barrows of nomadic tribes. While navigation was in its infancy, and Celtic canoes of hollow trees were risked upon the waters of British seas, the native population respected the resting-places of their departed countrymen, and, trusting to this feeling, gave only slight protection to their tombs |, but as warlike strangers succeeded in disturbing the peace of the community, they buried their dead more securely and ultimately, as though in imitation of other nations, raised over these megalithic vaults high mounds of earth, intermixed with small stones and fragments."

Continues....

In the same vol. of MS. letters, presented by will to the Bath Literary and Scientific Institution by the late Rev. J. Skinner, he describes the first opening of the tumulus at Wellow. He states, in his letter dated Dec. 1, 1815, that the "Barrow was partially opened about fifty years ago, when the farmer who occupied the ground carried away many cart loads of stones for the roads, and at length made an opening in the side of the passage, through which they entered the sepulchre. But Mr. Smith, of Stoney Littleton House, owner of the estate, hearing of the circumstance, bade him desist from hauling more stones; but as the discovery made some noise in the neighbourhood, the country people from time to time entered by the same opening, and took away many of the bones, etc. It was never properly examined till I had done it."

Thus to Mr. Skinner is due the honour of first calling attention to this interesting tumulus.

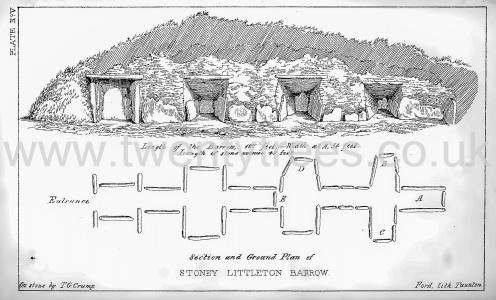

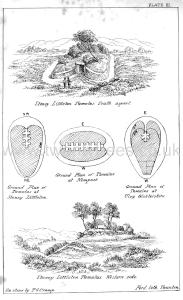

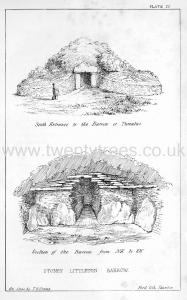

After Mr. Skinner had given this account to Mr. Douglas, Sir R. C. Hoare called the attention of antiquaries to this deeply interesting sepulchral tumulus, and by the aid of his friend Mr. Skinner caused every portion to be measured, and correct drawings to be made of it, which he sent to the Society of Antiquaries, accompanied by a description. These remarks and drawings are published in the Archaeologia, Vol. xix., p. 44. Sir Richard thus writes: "A new species of tumulus now excites my attention, which I shall denominate 'the stone barrow,' varying from 6 the long barrow,' not in its external, but in its internal, mode of construction. I have met," says he, "with some specimens, both in Ireland and Anglesea, but none corresponding in plan, or more perfect in construction. The form is oblong, measuring 107 feet in length, fifty-four in width over the barrow, and thirteen in height. It stands on the side of a sloping field, called 6 Round Hill Tyning,' about three-quarters of a mile south-west of W ellow church, and nearly the same distance to the south of Wellow Hays, the field in which is the Roman pavement, and a short half mile from Stoney Littleton House. The entrance to this tumulus faces north-west. A large stone, seven feet long, and three and a half wide, supported by two others, forms the lintern over a square aperture about four feet high, which had been closed by a large stone, apparently many years. When this was removed, it discovered to us a long narrow passage or avenue, extending forty-seven feet six inches in length, and varying in breadth. The straight line is broken by three transepts, forming as many recesses on each side of the avenue. The side walls are formed of large flat slabs, placed on the end. Where the large stones do not join, or fall short of the required height, the interval is made up with small stones, piled closely together. No cement is used; a rude kind of arched roof is made by stones so placed as to overlap each other." (See plate V.)

This is a very correct description. When the tumulus was investigated by Mr. Skinner, it was found that the interments had been disturbed, and their deposits removed, and only fragments of bones were met with in the avenue, which had probably been brought from the sepulchral recesses. In the furthermost recess, however, were a leg and thigh bones; at another point confused heaps of bones and earth. Jaw bones were also found, with the teeth perfect, and the upper parts of two crania, which were remarkably flat in the forehead; also several arm, leg, and thigh bones, with vertebrae, but no perfect skeleton. In one of the cists was an earthen vessel, with burnt bones; also a number of bones, which, from their variety, seemed to have been the relics of two or three skeletons.

At one point a stone was placed across the passage, and Sir Richard supposes that the sepulchral vault extended only thus far at first, and in later times was enlarged to its present extent. This seems very probable, from what has been found in barrows in Norway, of which something may be said further on.

No attention seems to have been paid to the size and symmetry of the stones which line the sides, which are put together as they have been procured, and do not indicate the use of any tools.

We find in this tumulus instances of both modes of interment— burial and cremation; but the latter seems to have been of more recent date. Sir. Richard observes: "I have never been able to separate with any degree of certainty, by two different periods, these different modes of sepulture." He also notices the peculiar conformation of the two skulls found in this tumulus, and says they were "totally different in their formation from any others which his researches had led him to examine, and appeared to him remarkably flat in the forehead." Mr. Skinner, in his MS. letter, says: "Two of the skulls appear to have been almost flat, there being little or no forehead rising above the sockets of the eyes, the shape much resembling those given in the works of Lavater, as characteristic of the Tartar tribes. I wish I could have preserved one entire, but I have retained the upper part of two distinct crania, which will be sufficient to confirm this remarkable fact." Dr. Thurnam has been at the trouble to trace out these remains, which he found had been bequeathed by Mr. Skinner to the museum of the Bristol Philosophical Institution, and he has described them in the I. Decad of the Crania Britamiica, a book manifesting great accuracy, extensive research, and intimate acquaintance with the subject of interments, while the facts brought under notice, being so carefully arranged, must contribute much to the assistance of future antiquaries. It is important that Dr. Thurnam should have been enabled, on examination of these remains, to ascertain their general resemblance to the crania found in the tumulus at Uley. "The frontal bone," he says, "is from the skull of a man of not more than middle age." "Its narrow and contracted character is very obvious, and its peculiarly receding and flat form fully justifies the observations of Sir R. Hoare and Mr. Skinner." And of the other he says that it has probably been that of a female of rather advanced age: "The forehead is narrow and receding, but less so than the former." "While it is satisfactory," says he, "to be able to establish this general conformity of type, i. e. in the Uley and Wellow tumuli, how much is it to be regretted that nothing beyond such meagre fragments remain to us of these skulls, taken as they were from a tumulus of so rare and remarkable a construction, and clearly belonging to the same period and people as that of Uley!"

And here I may properly pass on to say something respecting that tumulus which is of very similar character, though differing in arrangement, which was opened in 1854, and the particulars of which are given in the 44th No. of the Journal of the Archaeological Institute ot Great Britain and Ireland, and more recently in the I. Decad of the Crania Britannica. Dr. Thurnam describes this tumulus, which is locally termed a "tump," as a long barrow or cairn of stones, covered with a thin layer of vegetable earth. It had been planted, and in cutting down the timber in 1820, or in digging for stone, some workmen discovered the character of the tumulus, and found there two skeletons. Unfortunately the chamber which they came upon was broken up. In 1821 it was examined, and notes taken, but a further examination was made in 1854, under the direction of Mr. Freeman, when several members of the Archaeological Institute were present.

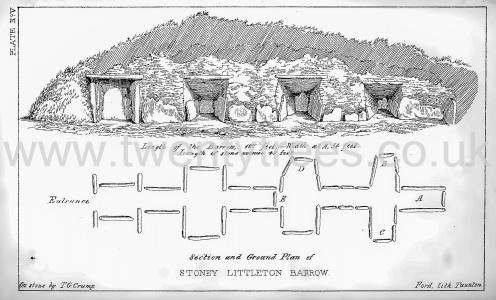

The length is about 120 feet, and the breadth, where it is greatest, 85 feet; the height about ten feet. It is higher and broader at the east end than elsewhere. The form of its ground plan resembles that well-known figure of the mediaeval architects, the "vesica piscis." At the east end, and about twenty-five feet within the area of the cairn, the entrance to a chamber was formed, in front of which the stones are built into a neat wall of dry masonry. The entrance is a trilithon, formed by a large flat stone, upwards of eight feet in length, and four and a half feet deep, supported by two upright stones, with a space of about two and a half feet between the lower edge of the large stone and natural ground. The entrance leads into a chamber or gallery, running east and west, about twenty-two feet long and four and a half feet wide, and five feet high. The walls of this gallery are formed of large slabs of stone of irregular shape, and set into the ground on their edges. Most of them are about three feet high, and from three to five broad. They are of a rough oolitic stone, full of shells, and must have been brought from about three miles distant. None of them present any traces of the chisel or other implement. The spaces between the large stones are filled up with dry walling. The roof is formed of large slabs of stone, which are laid across and rest on the uprights. There were two chambers on each side of this gallery; two of them have been destroyed. These side chambers are of an irregular quadrilateral form, with an average diameter of four and a half feet, and are constructed of upright stones and dry walling, roofed in with flat stones.

It seems to have been the custom to close up the entrances of these side chambers with dry walling, after interments had been made in them. This was the condition of that chamber which was opened in 1821. The roof also was constructed with overlapping stones, so as to form a dome, like the construction which appears at Wellow, and at New Grange, and Drowth, in Ireland; and Dr. Thurnam observes that very probably the whole structure had originally this character, as the tumulus appears to have been opened and ransacked previous to 1821.

It will be seen, on comparison of the plans of the two tumuli, that their internal structure is different in the arrangement of the cells. Those at Wellow are directly opposite, and at regular intervals, forming, so to speak, transepts, to a central passage; but at Uley they are grouped together in pairs, being likewise opposite, and this latter tumulus contains only two pairs of cells. In both these tumuli the central passage does not extend the entire length of the tumulus by many feet. The construction, however, of both is the same, the sides of the gallery and chambers being formed of large slabs of unhewn stone, planted on their edges, and the interstices filled in with dry walling of small stones. The roof in each is formed by courses of stone overlapping each other, and closed by a single flat stone. The cairn of stones heaped over the chambers has in each tumulus been neatly finished round the outer border with dry walling, carried to the height of two or three feet, which communicated by an internal sweep with similar walling, extending from the entrance to the chambers. This construction has lately been beautifully shewn at Wellow. (See plate III.)

Having been in the habit of visiting this tumulus at different times with friends, on walking over to examine it about three years since, I found that two of the chambers had collapsed during a severe frost, and the centre of the tumulus was in a ruined condition, and unless something was speedily done the whole would become a ruin. Having mentioned this to my co-Secretary for the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, we agreed to write to the owner of the property for leave to repair it, and at the same time to ask the Society to supply the means of paying the cost. Both these requests were readily granted, and proper workmen sent from Bath, with needful instructions, who completed the restoration so as nearly to bring back the tumulus to its original condition. Since this was effected, the owner of the property has been very desirous to protect the tumulus from further injury, and having consulted on the spot as to the best means of preservation, determined that a sunk fence should be placed all round, so as effectually to protect the cairn without injuring the view. On commencing this ditch, however, at the proper interval, it was discovered that a low wall, built of unmortared stones, on each side the doorway, was continued in front of the tumulus to the distance of twelve and fourteen paces on each side, and then turned suddenly, almost at a right angle, and continued round the tumulus to the northern end. This wall has been laid bare' all round, and proves to be the finishing of the cairn, which was afterwards covered over with vegetable mould, and made to subside gradually into the natural ground. (See plate III.)

The walling was quite perfect, except in one place in front, where a hedge and ditch had formerly been carried, and in places on the sides, where the roots of the trees growing on the cairn had broken through, and disarranged the regularity of the stone-work. When first opened, the stone- work presented the appearance of modern walling; and, in fact, all our modern dry walling seems to have originated with the primitive inhabitants of the land, and been continued to our times. At the northern extremity, where the ancient walling had been pulled down and carried away, the cairn has been repaired by modern walling, which is built up after the manner of the ancient, but somewhat higher for the sake of protection, but the juncture of the new with the old is marked by two upright stones introduced in the walling.

The portion of the tumulus which collapsed seems to have been that part which was first laid open when Mr. Skinner examined it, and from whence the stones, as he states, had been carried away. One of the workmen employed in repairing the cairn told me that he could remember, when a boy, stones being taken from the top and the side; this has somewhat depressed the elevation, and taken off from that appearance which it probably formerly presented, of a large boat or vessel turned keel upward.

We know, from Mr. Skinner's account, that the entrance, which is now found to have a wall extending on each side, was formerly quite covered over with earth, and presented the same appearance as any other part of the tumulus. At each successive interment the earth must have been removed. In clearing away this earth lately a fine Roman fibula was dug up. An ancient trackway leads to the tumulus out of the valley from the side of the brook.

Fairy's Toot [Map], which is now destroyed, was another of these singular tumuli. It is situated about a quarter of a mile east of Butcombe Church, on the declivity of some rising ground near Nempnett Farm, in the same parish. Its discovery was noticed by the Rev. Thos. Bere, rector of Butcombe, who made a drawing of it, and communicated the following account to the Gentleman's Magazine A.D. 1789:

"This barrow is from N. to S. 150 feet, and from E. to W. 76 feet. It had been known from time immemorial by the name of Fairy's Toot, and considered the haunt of fairies, ghosts, and goblins.

"The waywarden of the parish being in want of stones, ordered his workmen to see what Fairy's Toot was made of. They began at the south extremity, and soon came to a stone inclining west, and probably the door of the sepulchre. The stone being passed, an unmortared wall appeared on the left hand, and no doubt a similar one existed on the right. This wall was built of thin stone (a white lias). Its height was more than four feet, its thickness fourteen inches. Thirteen feet north from the entrance a perforated stone appeared, inclining to the north, and shutting up the avenue between the unmortared walls. Working round to the east side of it, a cell presented itself, two feet three inches broad, four feet high, and nine feet long from north to south. Here was found a perfect skeleton, the skull with teeth entire, the body having been deposited north and south.

"At the end of the first sepulchre, the horizontal stones on the top had fallen down. There,were two other catacombs, one on the right and the other on the left, of the avenue, containing several human skulls and other bones. A lateral excavation was made, and the central avenue was found to be continued. Three cells were here discernible, two on the west side and one on the east. These had no bones in them. The whole tumulus was covered with a thin stratum of earth, and overgrown with trees and bushes.

"The upright stones of which the cells are composed are stated to have been many of them two or three tons weight each, and in the very state in which Nature formed them. The number of cells can only be matter of conjecture. Supposing the avenue to have been 110 feet long, and about two feet thickness of wall or stone between each two cells, there would be room for ten cells on each side of the avenue." (See Sayer's History of Bristol.)

The writer of this notice conjectures this sepulchral tumulus to have been the work of the Druids, and the burying-place belonging to the Great Temple of Stanton Drew.

We cannot but remark here how the same method seems to have been followed here as at Wellow, of closing up a portion after interment, and it may be that the avenue was from time to time lengthened, and fresh cells made, as space was required. Nothing was found in the tumulus, neither urn nor coin, nor inscription of any sort, nor the trace of a workman’s tool. The large flag-stones had all their angles left, which might have been broken off, to facilitate transport, or to fit them better into place, if the use of the sledge-hammer had been known. The avenue of this tumulus seems to have run the entire length, being more complete in structure than either Uley or Stoney Littleton.

Mr. Phelps observes: The whole tumulus is now (1835) nearly destroyed; a lime-kiln having been built on the spot, and the stones burnt into lime.”

On July 17, 1856, I visited this spot, walking across the hill from Nailsea, and found the whole an entire ruin, no other trace of the tumulus left than a few heaps of small stones near the lime-kiln; which seems to have been dis used for some time. It is impossible now to trace the form of the barrow, which seems to have been constructed in the surface of the level ground. The situation of it is secluded, and somewhat melancholy, being in a small hollow valley, with a high hill on the north, and a small brook flows through the lower part of it. When the ground around was covered with forest, as it probably was in ancient times, the seclusion and quiet must have been complete. I made enquiry of the farmer, but he could give me no information respecting it, as he stated he was a new comer. Thus the very tradition of the spot will soon have passed away, and there would be no remembrance of this tumulus, were it not for the account given of it in the Gentleman's Magazine from whence Mr. Phelps’ and Mr. Sayer’s are taken.

We cannot sufficiently regret the loss of these most interesting monuments of former ages. When once destroyed they can never be replaced. The habits and manners of an extinct race, the primeval inhabitants of this island, are brought vividly before our minds at the sight of one of these sepulchres, and we can enter more fully into the condition of the people who constructed them, than by reading volumes of conjectural description.

It is a subject of great regret, that of the many skulls said to have been found in the Butcombe tumulus, none should have been preserved, as far as we know. The preservation of two portions of skulls from the tumulus at Stoney Littleton has enabled Dr. Thurnam to assert the identity of the race of people interred therein with those interred in the tumulus at Uley, in Gloucestershire, and it is not improbable that the skulls found at Butcombe would have also corresponded with them, and enabled us clearly to establish the fact that the same race had constructed these tumuli, as we are inclined to conjecture. If so, it is probable that the Dobuni, in whose territories the cham bered tumulus at Uley is situated, formerly had possession of Somersetshire, and, it may be, were driven out by the Belgse, who came over from the continent some centuries before the Christian sera, and whose boundary is generally considered to have been the Wansdyke. These tumuli are therefore, in all probability, older than Wansdyke, and, it may be, three or four centuries prior to the Christian sera. The same race of people that formed the Temple at Stanton Drew may have also formed the interesting cham bered tumuli at Stoney Littleton, Butcombe, and Uley.

Mr. Collinson, in a note to his History of Somerset, Vol. iii., p. 487, mentions three large barrows, called Grub barrows, which are situated in a piece of land called Battle Gore, which tradition says was the scene of a bloody battle between the inhabitants of the country and the Danes, who landed at Watchet in one of their piratical expeditions, A.D. 918. The Saxons here gained a victory over the Danes, who were commanded by Ohtor and Rhoald, and the dead are commonly said to have been buried under these tumuli. Mr. Collinson states that several cells composed of flat stones, and containing human remains, have been discovered. He does not, however, state when this was ascertained, and it is asserted that these have never been opened. It would be well worth ascertaining, if these barrows bore any relation in their construction to those we have been considering. This might be done by the Somersetshire Archaeological Society at small cost; and it is one of those points which our Society would do well to investigate, I should, however, be inclined to suppose that if they contain stone chambers they will be found to be similar in their construction to the tumulus at Lugbury, near Little Drew.

In treating of chambered tumuli, it would be a great omission to pass over that giant tumulus in Ireland, which has attracted such notice, and which still remains a won derful monument of a race coeval with those who formed the tumuli in England.

I cannot do better than describe it in the words of a gentleman who lately visited it, and has thus recorded the impression left upon his mind:

mpression left upon his mind:

It is' situated in the county of Meath, and on the banks of the river Boyne, and consists of an enormous cairn formed by immense quantities of small stones, water worn, and most probably boulder-stones collected from the banks of the Boyne, which flows below the gentle slope on which it stands. Time has covered the mound with green turf, and long after its construction it has been planted with trees, which cover its summit, while underwood creeps down its sloping sides. Four gigantic stones, hardly inferior to those of Stonehenge, about a dozen yards apart, sentinel the entrance, and form a portion of the circle which originally surrounded the base of the whole around and of which ten remain.

"Provided with light," says he, "I entered the external aperture, and after making my way along a narrow gallery, more than sixty feet in length, and from four to six feet in height, the sides of which were formed of rough blocks of stone, set upright, and supporting a roof of large flat slabs, I penetrated to the central chamber.

"I shall never forget the strange feeling of awe which I experienced 'as soon as I had thoroughly lighted up this singular monument of unknown antiquity. Wordsworth says on the sight of a somewhat similar monument

A weight of awe not easy to be borne

Fell suddenly upon my spirit—cast

From the dread bosom of the unknown past,’

And no person not totally insensible to the influence of the idea of vast shadowy antiquity, which such remains are calculated to excite, could stand under the Cyclopean dome of the cairn at New Grange, without some feelings akin to those of the poet. Indeed, next to the Pyramids^ to which it bears some resemblance, and only exceeded by them in grandeur and interest. There is probably, in Europe at least, no monument of the kind more imposing in size than this enormous mound. As’ soon as I was enabled with some distinctness to make out the plan of the gloomy crypt in which I stood, I found myself under a rude dome more than twenty feet in height, formed by huge flat stones overlapping each other, and the apex capped by a single immense block, being laid above the eloping masses, which gradually receded, giving its dome-like appearance to the roof, and formed a sort of key-stone to the vault.

This dome is itself supported by gigantic blocks of unhewn stone, forming an irregular octagon apartment, divided further by the same means into three recesses, giving to the whole area of the subterraneous temple a cruciform shape. The shaft of the cross would be replaced by the long corridor or entrance passage, and the three cells or recesses would form the head and arms of the cross.

In each of these cells formerly stood a shallow oval basin of granite, of which two still remain.

The sides of these recesses are walled with immense blocks of stone, many of which are covered with strange carvings, or rather scratchings, of the most uncouth form and character, evidently done before the stones were inserted into their present position, as they exist on portions now out of the reach of the hand of the carver.

"Some enthusiastic antiquaries have carried their zeal so far as to trace letters which they call 'Phoenician,' on these stones, and other's have styled them "Ogham characters;" but the more modern and judicious race of antiquaries consider them as mere marks, similar to those so frequently found by Sir E,. C. Hoare on the ancient British urns dis covered under the tumuli of the Wiltshire Downs.

And now it may be asked: What is the age of this singular work of elder days? and what the purpose for which it was constructed?

The best modern Irish antiquaries are agreed to refer it to the most remote period of Celtic occupation, and far beyond the time of the invasion of the Danes, to which people, like so many other Irish antiquities, it has been sometimes attributed. There exists in the Irish Annals a record of its having been opened and rifled by those invaders, when, even at that early date, it appears to have been considered an ancient monument.”

As to the assertion, from its cruciform shape, that it may be attributed to a period subsequent to the Christian aera, there seems to be no proof of any similar constructed barrow having been formed since the diffusion of Christianity, although we have seen that barrows were formed in foreign countries, and probably in this also, to a very late period.

As to the purpose for which New Grange Tumulus was constructed, "We believe," says a high recent authority, "with most modern investigators, that it was a tomb or great sepulchral pyramid, similar in every respect to those now standing on the banks of the Nile, from Dashour to Gaza, each consisting of a great central chamber, containing one or more sarcophagi, and entered by a long stone covered passage. The external aperture was concealed, and the whole covered with a great mound of stones or earth, in a conical form. The type and purpose in both is the same." That the oval basins originally contained human remains there can be little doubt but for the assertion that any human skeletons were found in the discovery of the cavern in 1699, there is no foundation. It was much in the same state as at present.

That the tumulus, together with the two nearly similar monuments which exist in the same locality, was rifled by the plundering Northmen a.d. 862, is recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters. How far anterior to the Christian aera the date of New Grange Tumulus may be placed, it is in vain to enquire; by most of the learned and intelligent modern archaeologists it is supposed to be coeval, by some to be "anterior to its brethren on the Nile." The same writer observes: "The tumulus at Wellow, near Bath, although on a much smaller scale, bears much resemformed of stones overlapping one another, and having a cap-stone instead of a key-stone.”

Here, then, we must bring to a close these remarks on Chambered Tumuli. There can be no doubt as to their very early date, and that they extend far beyond the limit of any written history, and lie enveloped in the same gloom of antiquity which enshrouds those wonders of our land —Avebury and Stonehenge. From the existence of similar remains in different regions, they seem to point to a people who had widely spread themselves over the face of the globe, and who were endued with great respect for the dead, and, it may be, amongst whom some knowledge of primeval traditions lingered.- We may not venture to assign any probable date, except that they were antecedent to the coming of the Romans, very probably by some centuries. Let us hope that what still exist in this country, few though the remains be, they may be preserved with care and respect; and if our Society, while it endeavours to unravel their hidden origin, calls attention to their preservation, it confers upon the history of our race, and upon succeeding generations, a lasting benefit.

REFERENCE TO PLATE V.

A.—Leg and thigh bones, with smaller fragments, were found.

B.—Confused heaps of bones and earth.

C.—Four jaw-bones, with teeth perfect; also, upper part of two crania; also, leg, thigh, and arm-bones, with vertebras; one of the side stones of this cell had fallen down across the entrance.

D.—Fragments of an earthen vessel, with burnt bones; also a number of bones, apparently reliques of two or three skeletons.

E.—Stone placed across the passage.