Stonehenge

Stonehenge is in The Ancient History of Wiltshire by Richard Colt Hoare Volume 1.

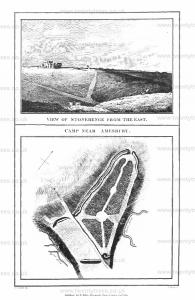

This remarkable monument is situated on the open down, near the extremity of a triangle formed by two roads; the one leading on the south from Amesbury to Wily, the other on the north from the same place, through Shrewton and Heytesbury to Warminster.1

A building of such an obscure origin, and of so singular a construction, has naturally attracted the attention of the learned, and numerous have been the publications respecting it; conjectures have been equally various, and each author has formed his own. Before I venture to give any opinion on this mysterious subject, it will be necessary for me to lay before my readers those of preceding writers concerning it.

Note 1. Its precise situation will be more satisfactorily explained by the annexed engraving.

The earliest accounts of Stonehenge, that have been transmitted to us by the monkish historians, are so deeply involved in the fable of antiquity and romance, chat little reliance can be placed on them; they must not, however, be totally omitted, as it is the duty of every historian to take notice even of traditions, however apparently improbable; for some portion of truth is often intermixed with fable, and many important facts have been traced to a most obscure origin.

These writers inform us, "that there was in Ireland, in ancient times, a pile of stones worthy admiration, called the Giants' Dance, because Giants, from the remotest parts of Africa, brought them into Ireland; and in the plains of Kildare, not far from the castle of Naas, as by fhrcc of art, as strength, miraculously set them up; and similar stones, erected in a like manner, are to be seen there at this day. It is wonderful how so many and such large stones could have been collected in one place, and by what artifice they could have been erected; and other stones, not less in size, placed upon such large and lofty stones, which appear, as it: were, to be so suspended in the air, as if by the design of the workmen, rather than by the support of the upright stones. These stones (according to the British History), Aurelius Ambrosius, King of the Britons, procured Merlin, by supernatural means, to bring from Ireland into Britain. And that he might leave some famous monument of so great a treason to future ages, in the same order and art as they stood formerly, set them up where the flower of the British nation fell by the cut-throat practice of the Saxons, and where, under the pretence of peace, the ill-secured youth of the kingdom, by murderous designs, were slain."

"Fut antiquis temporibus Hibernia lapidum congeries admiranda, que et CHOREA GIGANTUM dicta fuit, quia Gigantes eam ab ultimis Africa partibus in Hiberniam attulerant, in Kildariensi planicie, non procul à castro Nasensi, tam ingenii, quam virium opere mirabiliter erexerant. Unde ct ibidem lapides quidam aliis simillimi, similique modeo erecti, usque in hodriernum conspiciuntur. Mirum qualiter tanti lapides, tot etiam, et tam magni unquam in unum locum vel congesti fuerint, vel erecti; quantoque artificio lapidibus, tam magnis et altis, alii superpositi sint, non minores; qui sic in pendulo, et tanquàm in inani suspendi suspendi videntur, ut potius artificum studio, quam suppositorurn podio inniti videantur. Juxta Britannicam historiam lapides istos Rex Britonum Aurelius Ambrosias diviná Merlini diligentiâ, de Hibernia Britanniam adveti procuravit; et ut tanti facinoris egregium aliquod memoriale relinqueret, eodem ordine et arte quá priùs, in loco constituit, ubi occultis Saxonum cultris, Britanniæ flos cecidit; et sub pacis obtentu, nequitiæ telis, male tuta regni juventus occubuit.

Thus says Giraldus in his Topography of Ireland, which he wrote in the year 1187; by whose account we learn, that in his time certain stones placed upon each other, like those which now exist at Stonehenge, were visible on the plains of Kildare; but that these stones, originally brought from Africa, were conveyed to England by Merlin, and erected by Aurelius Ambrosias King of the Britons1, on the spot where some of his most distinguished subjects had been slain by the treachery of the Saxons. This event is thus recorded by Lewis, "In the reign of Vortigern, a conference was in his Ancient History of Britain: "In the reign of Vortigern, a conference was appointed to take place, near the Abbey of AMBRI, with Hengist the Saxon, and it was agreed that both parties should come without armour, But Hengist, under the colour of peace, devised the subversion of all the nobility of Britain, and chose out, to come to this assembly, his faithfullest and hardiest men, commanding every one of them to hide under their garment, a long knife, with which, when he should give the watch-word, every one should kill the Briton next him. Both sides met upon the day appointed, and treating earnestly upon the matter, Hengist suddenly gave the watch-word, and caught Vortigern by the collar; upon which, the Saxons, with their long knives, violently murdered the innocent and unarmed Britons, at which time: there were thus treacherously murdered, of earls and noblemen of the Britons, four hundred and sixty." After this massacre at Stonehenge in 461, repeated battles were fought between Ambrosius and Hengist. In the year 464, the former was defeated by the latter, near Richborough in Kent; but in 487, victory decided in favour of Ambrosius, who subdued his rival in a battie on the river Don, in the north of England; and in the following year, took him prisoner, and put him to death.

Thus says Giraldus in his Topography of Ireland, which he wrote in the year 1187; by whose account we learn, that in his time certain stones placed upon each other, like those which now exist at Stonehenge, were visible on the plains of Kildare; but that these stones, originally brought from Africa, were conveyed to England by Merlin, and erected by Aurelius Ambrosias King of the Britons1, on the spot where some of his most distinguished subjects had been slain by the treachery of the Saxons. This event is thus recorded by Lewis, "In the reign of Vortigern, a conference was in his Ancient History of Britain: "In the reign of Vortigern, a conference was appointed to take place, near the Abbey of AMBRI, with Hengist the Saxon, and it was agreed that both parties should come without armour, But Hengist, under the colour of peace, devised the subversion of all the nobility of Britain, and chose out, to come to this assembly, his faithfullest and hardiest men, commanding every one of them to hide under their garment, a long knife, with which, when he should give the watch-word, every one should kill the Briton next him. Both sides met upon the day appointed, and treating earnestly upon the matter, Hengist suddenly gave the watch-word, and caught Vortigern by the collar; upon which, the Saxons, with their long knives, violently murdered the innocent and unarmed Britons, at which time: there were thus treacherously murdered, of earls and noblemen of the Britons, four hundred and sixty." After this massacre at Stonehenge in 461, repeated battles were fought between Ambrosius and Hengist. In the year 464, the former was defeated by the latter, near Richborough in Kent; but in 487, victory decided in favour of Ambrosius, who subdued his rival in a battle on the river Don, in the north of England; and in the following year, took him prisoner, and put him to death.

Note 1. Aurelius Ambrosius succeeded to the kingdom of Britain, on the death of Vortigern. in the year 465. He was of Roman extraction, though educated in Britain. After a reign of thirty-two years he was poisoned by the contrivance of Pascetius:, son of Vortigern. Cressy, p. 221,

Another old writer, Jeffrey of Monmouth, has entered more circumstantially into the history of the stones, and attributes the erection of them to the aforesaid British King. He says "that Aurelius wishing to commemorate those who had fallen in battles and who were buried in the convent at Ambresbury, thought fit to send for Merlin the prophet, a man of the brightest genius, either in predicting future events, or in mechanical contrivances, to consult him on the proper monument to be erected to the memory of the slain. On being interrogated, the prophet replied "If you are desirous to honour the burying place of these men with an everlasting monument, send for the GiANTS' DANCE, which is in Killaraus (Kildare), a mountain in Ireland.1 For there is a structure of stones there, which none of this age could raise without a profound knowledge of the mechanical arts. They are scones of a vast magnitude, and wonderful quality; and if they can be placed here, as they are there, quite round this spot of ground, they will stand for ever." At these words, Aurelius burst out into laughter, and said, "how is it possible to remove such vast stones from so distant a country, as if Britain was not furnished with stones fit for the work?" Merlin having replied, that they were mystical stones, and of a medicinal virtue, the Britons resolved to send for the stones, and to make war upon the people of Ireland, if they should offer to detain them. Uther Pendragon, attended by 15,000 men, was made choice of as the leader, and the direction of the whole affair was to be managed by Merlin. On their landing in Ireland, the removal of the stones was violently opposed by one Gillomanius, a youth of wonderful valour, who at the head of a vast army exclaimed, "To arms, soldiers, and defend your country; while I have life, they shall not take from us the least stone of the GIANTS' DANCE." A battle ensued, and victory having decided in favour of the Britons; they proceeded ta the mountain of Killaraus, and arrived at the structure of stones, the sight of which filled them both with joy and admiration. And while they were all standing round them, Merlin came up to them, and said, "Now try your forces, young men, and see whether strength or art can do more towards the taking down these stones." At this word, they all set to their engines with one accord, and attempted the removing of the GIANTS' DANCE. Some prepared cables, others small ropes, others ladders for the work; but all to no purpose. Merlin laughed at their vain efforts, and then began his own contrivances. At last, when he had placed in order the engines that were necessary, he took down the stones with an incredible facility, and withal gave directions for carrying them co the ships, and placing them therein. This done, they with joy set sail again to return to Britain, where they arrived with a fair gale, and repaired to the burial-place with the stones. When Aurelius had notice of it, he sent out messengers to all the parts of Britain, to summon the clergy and people together to the mount of Ambrius (Ambresbury), in order to celebrate with joy and honour, the erecting of the monument. A great solemnity was held for three successive days; after which, Aurelius ordered Merlin to set up the scones brought over from Ireland, about the sepulchre, which he accordingly did, and placed them in the same manner as they had been in the mountain of Killaraus, and thereby gave a manifest proof of the prevalence of art above strength." page 250.

Note 1. This account is copied from Thompson's translation of Jeffrey of Monmouth.

What then are we to think of these ancient accounts of Stonehenge? In following the Iter of Ciraldus through Wales, 1 never had reason to complain of his want of accuracy in the description of places, however he might have staggered my faith in some of his marvellous stories. He appears to have seen with his own eyes, during his tour in Ireland, about 1186, an immense pile of stones, on the plains of Kildare, consisting of upright stones, with their imposts, and corresponding exactly with those at Stonehenge. "Lapides quidam simili modo erecti, usque in hodernum conspiciuntur." And he relates the wonderful voyage of the original stones brought From Africa to Kildare, and from thence into Wiltshire, on the credit of the British historians.

Jeffrey of Monmouth contradicts himself as to the placing of these stones; for he first says, "that Aurelius intended them as a memorial to those of his subjects who had been slain in the battle with Hengist, and who had been buried in the convent at Ambresbury; and afterwards tells us, they were set up round the sepulchre on the mount of Ambrius, which place (where Stonehenge now stands) is two miles distant from the supposed site of the convent.

However strange and improbable these ancient accounts may appear, some truth may lie hidden under the veil of fiction. I never saw a more likely spot, or one better situated for a Stonehenge, than the Curragh of Kildare, and regret very much, that, when in Ireland, I did not examine this verdant and extensive plain more attentively. I observed earthen works and barrows, the indicia of ancient population, and if ever a temple existed on this spot, I have no doubt its site, even at this remote period, might be discovered. I cannot possibly attribute so modern an æra to the erection of Stonehenge, as the time of Aurelius; otherwise we might suppose, that, under the story of Merlin and his arts, was designed the fact of some architect transporting the plan of such a temple from Kildare to Amesbury; or that one or two of the lesser circles, which now form a part of Stonehenge, and which are of a totally different stone from the larger circle, and oval, had been removed, This, indeed, was possible, but by no means probable; nor can I nod assent to any of these stories, except that of my friend Giraldus, who states having seen a pile of stones resembling Stonehenge, on the plains. of Kildare.

Another monkish historian, Henry of Huntingdon, who wrote about the year 1148, in the reign of king Stephen, places Stonehenge amongst the wonders of Britain; but candidly confesses, that no one can imagine by what art, and for what purpose, such large stones could have been erected. Apud Stanenges, ubi lapides miræ magnitudinis in modum portarum elevati sunt, ita ut portæ portis superpositæ videantur; nec potest aliquis excogitare qua arte tanti lapides adeo in altum elevati sunt, vel quare ibi construct; sunt." (p. 299)

All the information, therefore, that we have gained from the ancient authors respecting Stonehenge, is, that a huge pile of stones was erected on a hill near Amesbury, and that it was considered as one of the wonders of Britain. Such indeed, it may still be justly denominated, for no such building exists, not only in our own island, but even in the known world. For its plan and manner of construction, we must refer to modern writers, of whom a numerous list have employed their pens in the description of it. The first of these is the learned CAMDEN, the father of British antiquities, who, in the first edition of his BRITANNIA, printed in Latin, A. D. 1 586, thus expresses himself.

"Septentriones versus ad VI. plus minus à Sarisburia milliari„ in illâ planitie, insana. (ut Ciceronis verbo utar) conspicitur constructio. Intrà fossam enim ingentia et rudia saxa, quorum nonnulla XXVVIII. pedes altitudine, VII. latiudine colligunt, coronæ in modo triplici serie eriguntur, quibus alia quasi transversaria, sic innituntur, ut pensile videatur opus; unde Stonehenge nobis nuncupatur, uti antiquis historicis CHOREA GIGANTOM à magnitudine. Hoc in miraculorum numero referunt nostrates, unde verò ejusmodi saxa allata fuerint, cum totâ regione finitimâ vix structiles lapides inveniantur, et quânam ratione subrecta, demirantur. De his non mihi subtilius disputandum, sed dolentius deplorandum obliteratos esse tanti monumenti authores. Attamen sunt qui existimant saxa illa non viva esses, id est, naturalia et excissa, sed facticia ex arenâ purâ, et unctuoso aliquo coagmentata. Fama obtinet Ambrosium Aurelianum, sive Utherum ejus fratrem, in, Britonum memoriam, qui ibi Saxonum dolo, in colloquio ceciderunt, illa Merlini mathematici operá. Alii produnt Britannos hoc quasi magnificum sepulcrum eidem Ambrosio substruxisse eo loci, ubi hostili gladio ille periit, ut publicis operibus contectus esset, eâque extructione, quæ sit ad æternitatis memoriam, quasi virtutis ara."

"Toward the north, about six miles from Salisbury, is to be seen a huge and monstrous piece of work, such as Cicero termeth insana substructio. For within the circuit of a ditch, there are erected in manner of a crown, in three ranks or courses, one within another, certain mighty and unwrought stones, whereof some are 28 feet high, and seven feet broad, upon the heads of which, others like overthwart pieces, do bear and rest crosswise, with small tenons and mortises, so as the whole seemeth to hang, whereof we call it Stonehenge1, like, as our old historians term it, for the greatness, CHOREA GIGANTUM, the Giants' Daunce. Our contrymen reckon this for one of our wonders, and much they marvel from whence such huge stones were brought, considering that, in all those quarters bordering thereupon, there is hardly to be found any common stone at all for building; as also, by what means they were set up. For mine own part, about these points, I am not curiously to argue and dispute, but rather to lament with much grief, that the authors of so notable monument are thus buried in oblivion. Yet some there are that think them to be no natural stones, hewen out of the rock, but artificially made of pure sand and some gluey and unctuous matter, knit and incorporate together".

Note 1. This title is evidently Saxon, and derived from the words stan, stone, and henge, hanging.

The common saying is, that Ambrosius Aurelianus, or his brother, Uther, did rear them up by the art of Merlin, that great mathematician, in memory of those Britons, who, by the treachery of Saxons, were slain at a parley. Others say: that the Britons erected this for a stately sepulchre of the same Ambrosius, in the very place he was slain by his enemy's sword; that he might have of his country's cost such a piece of work and tomb set over him as should for ever be permanent, as the altar of his virtue and manhood."

We might naturally have expected better information respecting this singular structure from so learned a writer, and so zealous an antiquary as CAMDEN; he merely tells us the situation of this insana substructio, and makes so palpable a mistake in the numbers of the circles, that I question if he ever visited them himself: if he had seen them, he never could have stated the number of their ranks as three, instead of four; he also errs in their height; for none, as I shall shew hereafter, ever extended to the height of 28 feet. He retells the old and improbable tradition of their having been erected by Ambrosius Aurelianus.

In the year 1620, Stonehenge attracted so much the attention of King James the First, that, being at Wilton, the seat of the Earls of Pembroke, during his progress in the year aforesaid, he sent for the celebrated architect INIGO JONES, and ordered him to produce out of his own practice in architecture, and experience in antiquities abroad, what he could discover concerning this of Stonehenge." The result of his inquiry was not published till after the death of INIGO JONES, by his friend JOHN WEBB, Esq. who thus prefaces the work: "To the favourers of antiquity. This discourse of Stonehenge is moulded off and cast into a rude form, from some few indigested notes of the late judicious architect, the Vitruvius of his age, INIGO JONES. That so venerable an antiquity might not perish, but the world made beholding to him for restoring it to the desires of several of his learned friends have encouraged me to compose this Treatise. Had he survived to have done it with his own hand, there had needed no apology. Such as it is, I make now yours. Accept it in his name."

His descriptions are much more satisfactory than any of those preceding, being illustrated with ground plans, elevations, and views; yet still he has committed errors, which it will be my duty to point out; but I will first lay before my readers his account: of this singular structure.

"The whole work, in general, being of a circular form, is 110 feet in diameter, double winged about, without a roof, anciently environed with a deep trench, still appearing, about go feet broad. So that betwixt it and the work itself, a large and void space of ground being left, it had, from the plain, three open entrances, the most conspicuous thereof lying north-east; at each of which were raised on the outside of the trench aforesaid, two huge stones gate-wise, parallel whereunto, on the inside, were two others of lesser proportion. The inner part of the work, consisting of an hexagonal figure, was raised by due symmetry, upon the bases of four equilateral triangles, which formed the whole structure; this minor part likewise was double, having within it also, another hexagon raised, and all that part within the trench sited upon a commanding ground, eminent, and higher by much than any of the plain lying without, and in the midst thereof, upon a foundation of hard chalk, the work itself was placed; insomuch from what part whever they came unto it, they rose from an ascending hill."

He states the stones of the outward circle to be fifteen feet and a half high, and those of the greater hexagon, twenty. The order Tuscan, and the plan consisting of four equilateral triangles, inscribed within the circumference of a circle. He attributes the whale to the Romans, and the adjoining camps of Yarnbury and Ambresbury to Vespasian, when he conquered the Beigæ, who inhabited this district. He dates its origin from that period, when the Romans having settled the country under their own empire, and by the introduction of foreign colonies, reduced the natural inhabitants of this island unto the society of civil life, by training them up in the liberal sciences. Concerning the use to which Stonehenge was originally destined, our author is clearly of opinion that it was a temple, it being built with all the accommodations properly belonging to a sacred structure. For it had an interval, or spacious court, lying round about it, wherein the victims for oblation were slain, into which it was unlawful far any profane person to enter; it was separated from the circumadjacent plain by a large trench, instead of a wall, as a boundary about the temple, most conformable to the main work, wholly exposed to open view. Without this trench, the promiscuous common multitude, with zeal too much, attended the ceremonies of their solemn, though superstitious sacrifices, and might see the oblations, but not come within them. It had likewise its peculiar CELL, with porticos round about, into which, as into their Sanctum sanctorum, none but the priests entered to offer sacrifice, and make atonement for the people. Within the CELL an altar was placed, having its proper position toward the east, as the Romans used. Aræ spectent ad orientem, says Vitruvius."

Our author thus concludes his treatise: "I suppose I have now proved from authentic authors, and the rules of art, that Stonehenge was anciently a temple, dedicated to Cœlus, built by the Romans, either in, or not long after those times when the Roman eagles spreading their commanding wings over this island, the more to civilize the natives, introduced the art of building amongst them, discovering their ambitious desire, by stupendous and prodigious works, to eternize the memory of their high minds to succeeding ages.

We might naturally suppose that a man of such a profession, and so distinguished in it, would have been bath correct in his plans, and ingenious in his conjectures; but unfortunately he has erred in both: for in converting the two inner circles into an hexagon, he has adopted a plan which the building never could have assumed; and he has attributed its construction to a nation, amongst whom not a single model of the same kind can be found. He has told us that it was built by the Romans, after they had brought the natives of Britain to subjection, which could not have been earlier than the time of Claudius, and probably as late as Vespasian, under whom the celebrated Agricola completed the conquest of our island, and extended his victorious arm over the distant provinces of Caledonia. And can we for a moment suppose, that a people who had long before this period adopted the elegant architecture of the Greeks, and who had erected at Camalodunum, or Colchester, a temple to the Emperor Claudius, would on a sequestered plain, distant from any of their stations, have raised up a rude pile of stones, for which their own country could neither have furnished an idea, nor supplied a model?

Nor can I concur in opinion with this author about the entrances into the area of the work, which, he says, were three; or about the stones which he places near them. He has also erred in stating the situation, on which Stonehenge stands, to be higher than any of the adjacent plain.

The publication of this treatise by INIGO JONES, produced a reply in the year 1662, by WALTER CHARLETON, a physician.

This writer, who differs toto from his predecessor, attributes Stonehenge to the Danes, and the æra of its construction to the beginning of the reign of King Alfred the Great, during the period of his adversity, and the prosperity of the Danes. He concludes his dissertation by saying, "that of all nations in the world, none was so much addicted to monuments of huge and unhewn stones as the Danes appear to have been for many hundred years together; that they used to set up such, not only in their own country, but in all other places also, wherever the fortune of war had at any tirne made their adventures and achievements memorable, and more particularly in England and Scotland; that in Denmark, at this day, there stand many stupendous heaps of stones, in most particulars agreeing with that 1 have now discoursed; that upon a strict and impartial inquest, neither the ancient Britons, nor Romans, nor Saxons, are found to have any justifiable tide co the honour of founding that of Stonehenge; that no one of our old historians made mention of any such work, until long after the Danes had acquired the sovereign power in this island, and left sundry memorials of their victorious armies; that the great impairment of the fabric since that time of the Danish conquest, doth not evince it to be of greater antiquity; that neither the magnificence of the same at first, nor the vastness of strength, and skill in engines, required to the transportation and elevation of stones of such prodigious weight, are sufficient arguments to the contrary. Considering these things, I say, why may I not conjecture, that the Danes, and only the Danes, were the authors of Stonehenge?"

This treatise called forth another author, JOHN WEBB, Esq. of Butleigh in Somerset, whom I have before mentioned as having published the posthumous work of INIGO JONES. In a tedious and uninteresting dissertation of 228 pages, entitled "A Vindication of Stonehenge restored," he supports the Roman system laid down by his father-in-law, INIGO JONES, saying, that Mr. Jones's opinion, that the Romans, and only the Romans, were the founders of Stonehenge, appears in all probability, valid, and decked in the lively colours, and plain livery of truth. Nor let it be deemed presumption in me to assert it, seeing it hath this advantage over all others, concerning the same obscure subject, that it stands impregnable, and is not to be refuted.1

Note 1. The united works of Inigo Jones, Dr. Charleton, and Joha Webb, were püblished in the year 1725, in one folio volume.

AYLETT SAMMES, in his Britannia antiqua illustrata, printed in 1676, wrote a short treatise on Stonehenge, in which he recapitulates the opinions of INIGO JONES, and others, on the subject, and adds, "why may not these giants (alluding to the name Of CHOREA GIGANTUM given to Stonehenge), be the Phœcenicians, and the art of erecting these stones, instead of the stones themselves, brought from the furthermost parts of Africa, the known habitations of the Phœnicians?"