Tintern Abbey by O E Craster

Tintern Abbey by O E Craster is in Modern Era.

1956Tintern Abbey [Map], Monmouthshire by O. E. CRASTER, TD, MA, FSA Inspector of Ancient Monuments. London: Her Majesty’S Stationery Office. 1956.

Books, Modern Era, Tintern Abbey by O E Craster, Tintern Abbey: History

1131. Tintern Abbey [Map] was founded in 1131 for monks of the Cistercian order. Before that date Tintern has no known history. Two small Iron Age camps lie a mile or two to the south-west. To the Romans the place would have lain within the area bounded by their posts at Lydney, Caerwent, Usk, Monmouth, and their iron mines in the Forest of Dean, but it played no part in their scheme of things. In the eighth century King Offa of Mercia built the Dyke that takes his name along the crest of the hills on the other side of the River Wye. Nor was Tintern connected with Early Christianity: the old religious centres being at Caerwent, and at Llandogo, two miles to the north. The arrival of the Normans did not bring about any immediate change. The Norman leader, William Fitz Osbern, whom the Conqueror created Earl of Hereford, had established castles at Monmouth and Chepstow by 1071. Before long the Normans founded Benedictine monasteries at both these places: they were daughter houses of monasteries in Normandy, and served by French monks, who remitted a proportion of their annual revenues overseas. Associated, as they were, with the Norman invaders and, later, during the Hundred Years War, with the French enemy, which caused them to be classed as and suffer the disabilities of ‘alien priories’, these houses can never have had much influence on Welsh life.

The three new monastic orders, however, that sprang from the eleventh-century religious movement towards a stricter and simpler life, met with widespread success in Wales. The orders of Tiron, Savigny and Citeaux all observed the Rule of St. Benedict, but favoured greater seclusion, simplicity and manual labour, and each had a system of federation and supervision to ensure the maintenance of their statutes. Tiron and Savigny lay in the continental possessions of the English king, and were first in the field in sending colonies to Britain. Monks from Tiron founded St. Dogmaels in 1113, and, from Savigny, Neath and Basingwerk in 1130 and 1131. The Cistercians, as they were called after their original house at Citeaux in Burgundy, however, soon became predominant and later absorbed the Savigniac abbeys.

1128. The first Cistercian house in England was founded at Waverley in Surrey [Map] in 1128, being colonised by monks from L’Auméne in Normandy, itself a daughter house of Citeaux. Three years later another band of monks from L’Auméne settled at Tintern on land given them by Walter Fitz Richard, the Lord of Chepstow—or Striguil, to give it its medieval name. Walter, whose father had arrived with the Conqueror and founded the family at Clare in Suffolk [Map], had been granted Chepstow by Henry I. The site beside the Wye, which runs in a narrow valley between great rocky cliffs, must have seemed a wild enough place indeed to fulfil all the newcomers’ desires for remoteness.

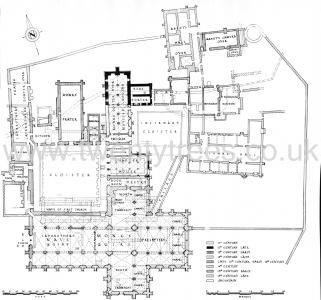

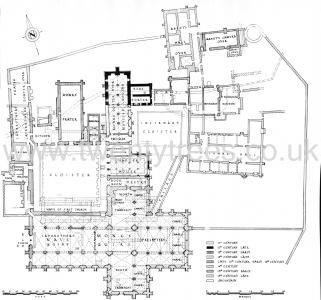

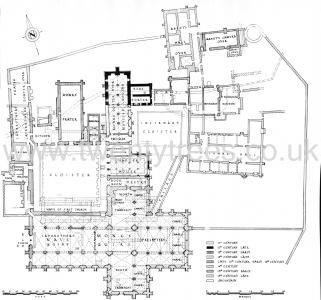

Like all Cistercian houses, the new abbey was dedicated to St. Mary. It was laid out in the customary fashion, save that, as elsewhere where the question of privacy or drainage to a river had to be taken into consideration, the monastic buildings were placed on the north instead of the south side of the church. Little is left of the original twelfthcentury abbey, which was on a smaller scale than the existing remains which replaced it in the following century. Nor is a great deal known about its early history. The normal contact was maintained with Citeaux: in 1188 for instance the Abbot of Tintern was suspended. by the deputies of the general chapter.

Tintern Abbey, County Wexford [Map] was founded around 1200 by William Marshal 1st Earl Pembroke (age 54), as the result of a vow he had made when his boat was caught in a storm nearby. Once established, the abbey was colonised by monks from the Cistercian abbey at Tintern in Monmouthshire, Wales, of which Marshal was also patron. To distinguish the two, the mother house in Wales was sometimes known as "Tintern Major" and the abbey in Ireland as "Tintern de Voto" (Tintern of the vow).

Tintern played no part in founding the other Cistercian houses in Wales—these largely sprang from Whitland [Map]. In 1139 monks from Tintern colonised a daughter house at Kingswood [Map], in Gloucestershire, and in 1200 sent out their only other colony to Tintern Minor [Map], in Co. Wexford, which was founded by William Marshall, who had acquired the lordship of Striguil by his marriage to the Clare heiress, to fulfil a vow he made for his deliverance from shipwreck on the Irish crossing. Tintern Abbey was evidently involved in the minor war of 1233 between Richard Marshall and the king, for the following year the latter granted the abbot 40 mares and their foals of three years from the Forest of Dean in consideration of his losses. But apart from this, Monmouthshire lay outside the area in which the struggle between the English and Welsh was carried on, and was not troubled by fighting.

During the thirteenth century Tintern Abbey [Map] was almost completely rebuilt. A start was made round about 1220 with building a new refectory. From about the year 1200 it had become the Cistercians’ practice to build their refectories with the long axis running north and south instead of east and west, thus allowing more room for the laybrothers, who occupied the western range. The new refectory was accordingly built in current fashion. Following this the rest of the claustral buildings were altered or rebuilt. A start on rebuilding the church was made in the year 1270 under the patronage of Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk 1270-1306, whose family had succeeded to the lordship of Striguil through marriage with a Marshall heiress. The new church was laid out slightly to the south of the original one, allowing for a larger cloister and for the choir of the old church to remain in use until the new one was ready. The high altar was first used in 1288, though the whole work was not finally completed until 1301, by which time it had been 32 years in building.

On Roger Bigod’s death in 1306 his lands passed to the Crown. Edward II granted them to his half-brothers, creating the eldest, Thomas of Brotherton, Earl of Norfolk and Lord of Striguil. The royal connection did not, however, save Tintern from the burden caused by the Crown’s growing practice of ordering monastic houses to provide maintenance and accommodation for its retired servants for the rest of their lives. In 1319 the abbot was asked to take in a monk from the Cistercian abbey of Holmcultram [Map] in Cumberland, which had been laid waste in the Scottish wars.

In 1326 Edward II (age 41) was himself a refugee, and spent two nights at the abbey [Tintern Abbey [Map]] on his way from Gloucester to Chepstow. Whilst at Tintern the king granted the abbot the fishing and the half of the weir across the Wye at Bykelswere which had belonged to the royal castle of St. Briavels [Map]. In the next reign a dispute broke out because the abbot had raised the height of this and the other weirs near the abbey, preventing Henry, Earl of Lancaster, from carrying stores to his town of Monmouth. The king sent a commission to enquire into the matter, who threw down two of the weirs. Whereupon the abbot petitioned the king that all the weirs, except the half of Bykelswere, which had been granted the abbey by Edward II, were in the lordship of Striguil, and, consequently, in the jurisdiction not of the Crown but of the Earl of Norfolk.

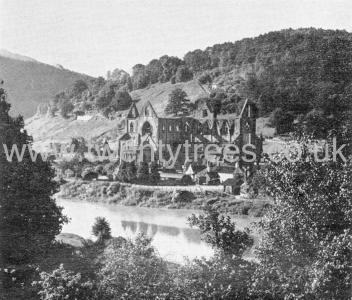

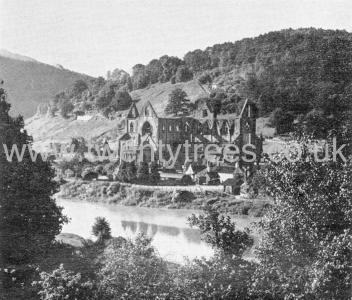

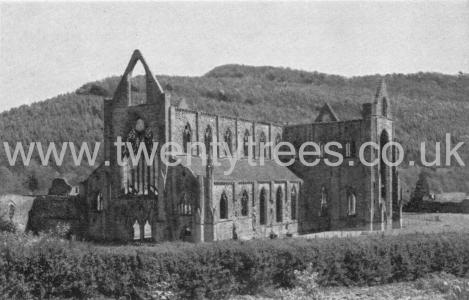

Tintern Abbey from across the Wye

It is only when matters such as the dispute over the weirs came to the notice of the king, and are consequently noted in the royal records, that we can learn of events at Tintern. Thus we know of the abbot embarking at Dover on his way to attend the general chapter at Citeaux in 1331 at a time when wars with France caused the king to keep check on everyone leaving the country. In the following year one of the Tintern monks became prior of Goldcliff [Map], an alien priory on the Severn estuary to the south-east of Newport, but was removed on the discovery that the papal bull presenting him was a forgery; though not before he had alienated part of the priory’s lands.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century Tintern Abbey was at its zenith. The rebuilding started in the previous century continued with the completion of the church and the erection of the abbot’s hall. In 1349, however, the Black Death swept the country. There is no record of it at Tintern, though we learn of Abergavenny Priory [Map] being impoverished by the pestilence. The effect on the economy of the country was far-reaching: the acute shortage of labour raised the price it could command, and hastened the change-over from a feudal economy based on service to one based on wages. The Cistercian monasteries had large agricultural interests, and did not escape the effects of the change. After the Black Death it was almost impossible to recruit lay-brothers. The lay-brothers, or conversi, who had normally outnumbered the monks, took the monastic vows of obedience, poverty and chastity, occupied quarters in the western range, attended their own services in the nave of the church, and were responsible for the agricultural, building and domestic activities of the monastery. From the middle of the fourteenth century onwards they ceased to play an important part.

We know little of Tintern in the fifteenth century. During the national rising led by Owen Glyndwr there was fighting near Grosmont and Monmouth, but the abbey did not suffer any material damage, though we hear of the abbot in 1407 being pardoned by the king for his failure to collect taxes in the diocese of Llandaff, as the country was laid waste by the rebellion of the Welsh. The only building work carried out during the century was the division of the infirmary hall into cubicles, each with its own fireplace. In 1468 William Herbert of Raglan was rewarded for his support by being created Earl of Pembroke by Edward IV, and at the same time he acquired the lordship of Striguil from the Duke of Norfolk. Tintern Abbey thus passed under his patronage. The new earl was beheaded after the Yorkist defeat at Edgecote in the following year, and his body was taken to Tintern, to which he had left a bequest for rebuilding the cloisters.

William of Worcester, the chronicler and traveller, and former secretary of Sir John Fastolf of Caister, visited the abbey in 1478. It is from him that we know the date when the new church was first used. He also recorded that there was a bell tower over the crossing, and that the glass of the great east window showed the arms of Roger Bigod.

1536The coming of the Tudors to the throne, and the establishment of a strong monarchy, might have been expected to have opened an age of peace and prosperity for Tintern. But this was not to be. To Thomas Cromwell (age 51), casting round to raise funds for his master Henry VIII, the wealth of the religious houses appeared as a great prize. The monasteries were not in a strong position to withstand attack. The monastic ideal had lost its original appeal. Standards were low, and the life of the monks had become increasingly secular. The closure of the alien priories during the French wars, and, more recently, the suppression of many religious houses (notably 21 by Wolsey) on the grounds of misconduct, and the conversion of their funds to endow new schools and colleges, provided a ready precedent. In 1535 there was a general visitation of the monasteries, and in the following year an act was passed suppressing all those with revenues below £200 a year. This comprised about two-thirds of the total number of religious houses, and amongst them was Tintern Abbey [Map], which had an income of £192. In 1537 the site was granted to Henry, Earl of Worcester (age 40), whose father had married the Herbert heiress, and who was consequently the abbey’s patron at the time of its suppression.

The lead and bells of the monastic houses were normally reserved for the Crown, and there is a record of the payment of £8 to the king’s plumbers in 1541 for melting them at Tintern. Part, if not all, of the metal was evidently bought by the Earl of Worcester; for in 1546 he paid £166 outstanding to the Crown for lead and bells from Tintern, and these he no doubt used for his castles at Chepstow and Raglan. The abbey thus became roofless within a few years of the Dissolution, though it is possible that Sir Thomas Herbert, who lived at Tintern in the seventeenth century, may have occupied some part of the monastic buildings.

From the sixteenth century onwards Tintern became important for its brass and iron works, and especially for its manufacture of wire. This industry did not encroach on the abbey precincts, though many cottages were built to both the north and the west of the church. The church itself has, with a few exceptions, remained in much the same state since losing its roof. The piers of the north nave arcade were already missing by 1801. The screen between the first pair of piers west of the crossing was still in position in 1854 but was later removed.

In 1901 the site [Tintern Abbey [Map]] was bought by the Crown from the Duke of Beaufort (age 53), the descendant of Henry, Earl of Worcester, and in 1914 its administration was transferred to the Office of Works, now Ministry of Public Building and Works. Since then the piers of the south nave arcade have been saved from collapse, the ruins consolidated, and the site gradually cleared of encroachments.

Books, Modern Era, Tintern Abbey by O E Craster, Tintern Abbey: Description

The Church

The visitor enters the abbey through the outer parlour, containing the modern ticket office, and, turning right, reaches the church through a door set diagonally in its north-west angle. The church, apart from its roof, vaulting and the north arcade of the nave, stands virtually complete. It consists of a presbytery with aisles, north and south transepts with eastern aisles containing chapels, and an aisled nave.

Presbytery

The presbytery consists of four bays. The piers formerly had detached shafts in the angles, and the bands which separated the upper and lower shafts can be seen. The presbytery was separated from its north and south aisles by 9 ft-high walls; only the ends of these, against the piers between which they were built, now remain.

The foundations for the high altar are just west of the first pair of piers; and behind it ran the processional way for which there must have been openings in the screen walls of the first bay. The raised platform against the east wall of the church carried the altars of chapels. In the middle of this wall there is a low arch indicating a barrow way used by the builders during the construction of the church.

The east window occupies nearly the whole of the end wall of the church. Originally of eight lights, it still retains its great central mullion and rose window; but the rest of the tracery has gone, and with it the stained glass which portrayed the arms of the founder.

Above the arcade the walls are divided by two string-courses. There is no triforium, and the lower section is blank. In the upper part, at a level above the aisle roofs, are the clerestory windows: these were of two lights and had sexfoil heads and detached shafts in their inner splays. In between these windows arc the springers for the vaulting, rising from triple shafts carried on corbels between the arches of the arcade. The vaulting, both here and throughout the church, was carried on simple transverse and diagonal ribs. There were stone bosses at the intersections of the latter, and six of these bearing a variety of foliate designs now rest on the ground between the arches of the arcade. The roof-space above the presbytery vault. was lit by a large three-light window which has lost most of its tracery.

The presbytery aisles both had an altar against their east wall, with a three-light window above and two-light windows in each bay. These all had detached shafts in their inner splays, except for that in the third bay of the north aisle. This window is later than the others, and a break in the masonry to the east of the doorway below it can be seen. The doorway (its jambs were rebuilt in 1904, but some of its original detail can be seen on the exterior) gave access to the passage leading to the infirmary. This part of the aisle was built after the rest because it lay within the east end of the first church, which would have continued in use until the new one was ready. The foundations of the first church are marked out on the ground, and reference to the plan will make the sequence more easily understood.

The springers for the aisle vaulting were carried on the capitals of the piers on the inner, and on triple shafts rising from a low stone bench on the outer, sides of the aisles. In the first bay of the south aisle are the remains of a piscina.

Crossing

The centre part of the church between the presbytery and the nave and the transepts retains its four great arches. Like the rest of the church it had a vaulted ceiling, and above this there was a low bell tower. This central area, together with the first bay of the nave, was used as the monks’ quire. Screen walls, of which the remains can be seen projecting from the two western piers, separated it, at any rate partially, from the transepts. The clustered shafts of the two western piers are not carried down to the ground, but rise from corbels in order to allow room for the monks’ stalls which stood against the side walls.

Transepts

The north and south transepts are of similar design, each having three bays and an eastern aisle occupied by a pair of chapels separated from each other, and from the presbytery aisles, by screen walls. In two of these chapels, the bases of the altars are still in position.

The great window at the south end of the south transept originally had six lights; its tracery is missing, but detached shafts in its upper jambs still remain in position. Beneath this window, surmounted by an intruding pediment, is a doorway of four orders.

A circular stair in the south-west angle of the south transept gave access to the triforium passage, which led into the roof-space above the vault of the south aisle of the nave, and also, through a shoulderarched doorway, to the roof. The roof-spaces above the south transept aisle and the south aisle of the presbytery were reached down a stair from the roof, through the doorway to be seen in the south-east angle of the crossing pier.

The east walls of the transept aisles have two three-light windows, and the south has a window in its end wall. This latter is omitted in the north transept aisle owing to the abutting claustral buildings. On this north wall, however, some of the plaster, which would originally have covered all the wall surfaces of the church and would probably have been coloured, with imitation joints depicted by red lines, still remains in position.

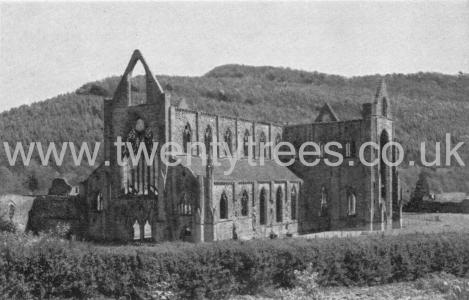

The abbey church from the south-east

In the west wall of the south transept is a pair of two-light windows opposite those of the aisle. Both transepts have three clerestory windows in their east and west walls, the jambs of which (except those of the east wall of the south transept, where there is no triforium passage) are carried down to the string-course above the main arcade.

The building sequence of the north transept is complicated owing to it having contained the east end of the first church, and is most easily followed by reference to the plan at the end of the guide. The north wall contains a large six-light window. Its tracery is complete, the lower part, which did not clear the level of the roof of the monks’ dormitory abutting against its outer side, being treated as wall panelling.

n the north-west angle of the north transept was the night stair. The existing steps are modern, but they are built on the line of the original ones leading to the doorway through which the monks entered the church from their dormitory for night-time offices. In this angle also, there is a circular stair (not open to the public) leading from dormitory level to the triforium wall passage, which gave access to the roof-spaces of the north aisles of the presbytery and nave. The stair also led, through the doorway that can be seen high up, to the main roof-spaces above the vaulted ceilings, and to the roof. The wall passage runs round all three sides of the north transept; it is slightly differently treated from that of the south transept, having a flat instead of a shouldered roof.

There are two windows in the west wall of the north transept at clerestory level; but the windows below, which would have had to have high sills to clear the roof of the cloister walk, are omitted. The doorway at ground level in the north end of the transept leads to the vestry. The east wall has abutments for two flying buttresses, a feature that does not occur elsewhere at Tintern.

Nave

The aisled nave consists of six bays: its north arcade is missing, though the bases of the piers remain. The south arcade has been saved from collapse by a system of steel reinforcing, part of which has been concealed by reforming the roof over the south aisle. The monks’ quire extended from the crossing into the first bay of the nave, from the rest of which it was separated by the pulpitum. This was a massive stone screen, containing a central doorway and a stair, which stood between the first pair of piers. There was a second screen between the next pair of piers, against the west side of which stood the lay-brothers’ altar. The latter’s quire occupied the fourth and fifth bays of the nave, and their stalls would have stood against the screen walls built between the piers. From the remains of these walls it will be seen that the south aisle was probably completely cut off from the nave, and could only be entered through its west door or from the south transept. The lay-brothers entered their quire through the west bay of the north arcade, which was left open. There was also a doorway from the north aisle in the screen wall in the second bay.

The two eastern bays of the nave were completed first, enabling the monks to bring their new quire into use. The remainder of the nave was finished later, and the transition from the first to the second period of building can be seen in the change from the use of detached to attached shafts in the jambs of the windows: this occurs after the second bay of the clerestory, which has two-light windows with sexfoil heads, and after three and three-quarter bays of the south aisle where the break in the masonry can be readily seen.

The west end of the nave has in it a great seven-light window with nearly all its tracery intact. Above it another window lit the roof-space over the vault, and below is a twin doorway, the exterior of which and the west front should be looked at next. The doorways have trefoil heads, and are contained within an arch filled with tracery and decorated wall panels; whilst on either side are wall panels of similar character. At the south-east angle one of the graceful octagonal spirclets that surmounted the buttresses survives. The column bases in front of the west door are all that remains of a fifteenth-century arcaded porch which is believed to have contained a chapel.

The south aisle has two-light windows with sexfoil heads except for the two westernmost which are of the second period. The latter have quatrefoil heads and have high sills, apparently to suit the ground level, which the external plinth shows to have risen at this point. A number of roof bosses, two bearing faces, are placed on the floor of this aisle. Both nave aisles have three-light windows in their west walls, though of slightly different design, and their roof-spaces each have a lozenge-shaped ventilator.

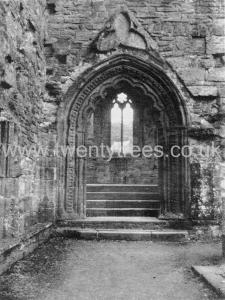

The north aisle is of the second period. Its two-light windows with quatrefoil heads have high sills in order to clear the roof of the cloister walk. The eastern bay is later still, containing the richly decorated processional doorway of fourteenth-century date, with a window above it of different design to the others. The doorway in the north-west angle of the aisle was used by the lay-brothers for entering the church from their quarters in the western range.

Few tombs remain in the church and probably the only one in its original position is that under the north arch of the crossing. This has a covering slab with an incised floriated cross and the inscription HIC: IACET: NICHOLAUS: LANDAVENSIS . . (Here lies Nicholas of Llandaff). The grave belongs to the first half of the thirteenth century, and cannot have long been in position in the south transept of the first church before it was buried under the floor of the new one. There was a Nicholas who was Precentor and Treasurer of Llandaff c. 1191-1218, and it may well be that he entered the monastery before his death, and that this is his grave.

Another interesting tombstone is within the railing in the south aisle of the nave. It is an incised slab with a large fish and a trio of smaller ones upon it and in Gothic letters HIC IACET WILL(E)LMUS WELLSTED. Beside this slab there is another with a cross and staff without any inscription other than the name BROWNE and a mason’s mark, possibly added at a later date.

The Monastic Buildings

Cloister

The cloister lies on the north side of the church. It was enlarged during the rebuilding of the abbey in the thirteenth century, part of its site having been occupied by the first church. It consisted of four covered walks round the sides of an open court. Only the foundation course of the walls on the outer side of these walks remains. They had external buttresses, between which there would have been windows. A large number of the corbels which carried the lean-to roofs are still in position, and also a stone bench which ran round three sides of the cloister.

The cloister walk nearest the church was customarily used by the monks for their studies, order being kept by the prior, the remains of whose canopied seat can be seen in the centre of the church wall. Opposite it there is a rectangular stone foundation which may have supported a water cistern.

In the east cloister walk there is a round-headed recess with another blocked one beside it. These were the cupboards for books that were in use in the cloister. They are of twelfth-century date, this section of the church wall having also formed part of the cloister of the first church. The northern cupboard was blocked in the fifteenth century, when the rebuilding of the cloister with a stone vaulted roof was begun; but, as the scanty remains of this late work show, it had made little progress by the time of the Dissolution. The buildings round the cloister will now be described in turn.

Book Room and Vestry

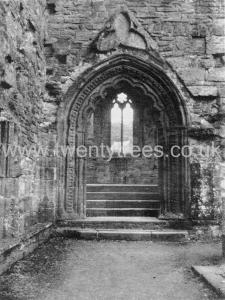

The first doorway in the eastern range has a central mullion and fine, deeply carved, mouldings and tracery, and is of fourteenth-century date. It leads into a long room. This was originally divided into two by a cross-wall, and the front part, which had a barrel vault, formed the book room. The rear part, which was entered from the church, was the vestry. It has a vaulted roof of three bays, the easternmost of which survives together with its tiled floor.

Interior of the church looking east

Various stone fragments from the church have been collected here, amongst them the mutilated effigy of a knight in chain armour that must date from c. 1200, and another, also much disfigured, of the Virgin and Child. There is a large double grave slab with inscriptions in lead-filled incised Lombardic capitals. They read:

[HIC J]ACET: H[ENRICU]s: [D]E: LANCAUT: QU[ONDAM A]BBAS: DE: VOTO: and HIC: JACE[T: JOHA]NNES: DE: LYUNS.

Lancaut is the name of the peninsula on the Gloucestershire side of the Wye two miles below Tintern. The abbey of de Voto was Tintern Minor [Map], the daughter house in Ireland. The stone is undated, but probably belongs to the thirteenth century.

Above the book room the line of the roof of the monks’ dormitory will be seen on the church wall, and also one jamb of a doorway that led to a room over the eastern part of the vestry; this was the normal position for the strongroom in which the house’s most valuable possessions were kept.

Chapter House

The next chamber to the north is the chapter house. Here the monks met daily to discuss the business of the house, correct faults, and hear a chapter of the Rule of the Order read. Built originally in the twelfth century, this room was largely rebuilt in the following century, from which time the doorways, with their richly clustered detached shafts, twin aisles and vaulted roof all date. It was lit by windows in its east end, and in the first and possibly second bays: that on the south having to be blocked when the vestry was built. The monks sat on a stone bench that ran round the sides of the room. The foundations of this bench and part of the tiled floor can be seen. In the cloister walk opposite the chapter house door there are five grave slabs, their inscriptions are no longer legible.

Parlour

The room immediately north of the chapter house was the parlour, where conversation between the monks was allowed. It is a long narrow chamber entered from the cloister by yet another richly carved doorway, and lit by a window in its east end.

The narrow space north of the parlour, between it and the line of the buildings of the north range, is believed to have contained the original day stair to the dormitory. North of this again is the passage leading from the cloister to the infirmary buildings, which will be described later (page 22).

Novice' Lodging

On the north side of the passage, and occupying the remainder of the eastern range, is the novices’ lodging. The novices comprised the new entrants to the monastery, who underwent a period of probation before graduating as monks.

This fine hall was originally only half its present length. Its southern half, now masked by later work, formed part of the first lay-out of the abbey buildings. It was enlarged northward in the latter part of the twelfth century, and a window of this date survives at the north end of the east wall. In the thirteenth century stone vaulting supported on central piers was inserted, buttresses were added to give the necessary additional support, and the narrow lancet windows were constructed.

Dorter

The monks’ dormitory or dorter occupied the whole first floor of the eastern range, and the line of its roof against the church has already been noted. From the vantage point of the novices’ lodging it will be seen how the range, which was laid out centrally with the transepts of the original church, is overlapped by the wider transepts of the thirteenth-century building.

Reredorter

Projecting eastwards at right angles to the novices’ lodging, and built at the same time as the latter was enlarged, is the reredorter or latrine. The southern half of this building was vaulted, and had a door and windows towards the infirmary cloister. The northern half contains the main drain, through which formerly flowed a stream of water. There would have been a row of cubicles over the drain; but it is uncertain whether these existed at both first-floor and ground level.

Northern Range

This range, the eastern part of which still stands to second-floor level, was rebuilt in the thirteenth century. It contains the warming house, refectory and kitchen. The archway near the north-east angle of the cloister leads into a vaulted passage on the east side of which is the door to the novices’ lodging. There are two arches at the north end of the passage. That to the east led to the day stair to the monks’ dormitory. Only fragmentary remains of the stair, which superseded the earlier day stair next to the parlour, now exist; but the higher level of the inner arch to allow headroom on the stairs will be noticed. Some of the original plaster that once covered all the walls can be seen in this area. The second arch contains a doorway leading down to a yard.

Warming House

The first chamber to the west, entered from the cloister walk by a doorway of two orders, is the warming house. This was the only place, apart from the kitchen and infirmary, where a fire was allowed. There is a central fireplace supported on four piers, with arched passageways on either side allowing all-round access to the fire. On the north, part of the hooded cowl of the fireplace is still in position. The southern half of the building has a rib-vaulted roof of two bays, and the metal dowels for fixing small bosses at the intersection of the ribs can be seen. The northern half, which extended beyond the upper floors, has a simple open roof whose line can be readily seen. At a later period the central fireplace went out of use, its chimney was blocked, and a new smaller fireplace built at the north end of the room.

The upper floors above the warming house and passageway are no longer accessible. On the first floor there is a large chamber lit towards the cloister by two lancets and an earlier round-headed window, and by two lancets on the north. West of this is a second room with a vaulted ceiling and a small square-headed window on the south and a lancet on the north. These rooms were reached from the monks’ dormitory, and were occupied by the prior who was responsible for its discipline. In the sixteenth century a second storey was added and two three-light and one single-light Tudor windows survive on the north, and one on the south.

Frater

The large doorway opening off the centre of the north cloister walk is that of the frater, or monks’ dining hall. On either side of it, flanked by arcading with detached shafts, are two recesses: the larger contained the bowls where the monks washed before meals, and the smaller contained towels. The fine dining-hall is 84 ft long and 29 ft wide. It was built in the early thirteenth century to replace the first frater which ran east and west. On its east side it retains four ofits four-light windows with much of their heavy plate tracery. These windows were arranged in pairs, each pair forming a bay of which there were four. The moulded arches and detached banded columns are continued as panelling round the south bay and end wall.

In the centre of the west side of the hall is the doorway, vaulted lobby, and part of the stairs that led to the pulpit, where one of the monks read from the scriptures during meals.

Near the south-east corner is the door leading to a vaulted pantry or storeroom, while close by in the south wall are a pair of recesses. The one on the left with a drain was for washing plates and spoons, and the other contained a cupboard for storing them.

At the south end of the west wall there is a serving hatch from the kitchen and, in the end wall nearby, the recess for a drop-down table.

The processional doorway from the cloister to the church

Kitchen

The kitchen occupies the remainder of the north range. Its internal arrangement has been largely destroyed by a cottage which formerly stood on the site. A cross-wall (see plan) once divided the building into two rooms, the smaller one to the east being used as the servery. Both rooms had doorways to the cloister. The main one also had a door leading to the kitchen yard on the north, and another on the west through which food was carried to the lay-brothers, dining-hall in the western range.

There was a large fireplace in the wall dividing the kitchen and servery. This wall continues northwards over the main drain, and probably formed the east wall of the scullery, but the walls of later cottages have obscured its form.

Western Range

In Cistercian houses the range of buildings on the west side of the cloister was occupied by lay-brothers. At Tintern the western range, as rebuilt in the thirteenth century, does not abut against the church as was normal, but starts some forty feet to the north. The southern part stands to first-floor level, and the range has a total length of over 180 ft.

Outer Parlour and Porch

The chamber on the ground floor at the southern end of the range, within which the modern ticket office has been built, is the outer parlour, where the monks could meet visitors from outside the abbey. It had a vaulted ceiling. Outside the parlour there is a porch with a stone bench on its south side, and a large arched recess on the north. In the fifteenth century a stone vaulted roof was added, and the inner doorway was rebuilt.

Access to the two rooms above the porch and parlour was provided by the stair reached through the doorway at the north-west of the latter. These formed the cellarer’s lodging, and the larger of the rooms has a thirteenth-century window on its south side with one of the following century inserted.

The outer parlour had a large doorway to the cloister, and another in its south wall opened on to the covered walk by which the laybrothers reached the church. On the east side of this walk are the remains of the stair which led, by way of a passage, to the lay-brothers’ dormitory on the first floor of the building beyond the parlour. Near the foot of the stair are the remains of a cistern which was supplied by a lead pipe. The water supply is supposed to have been drawn from the spring called Coldwell on the hillside to the south of the abbey.

Cellarium

To the north of the outer parlour is a square vaulted chamber with no direct access to the cloisters. It had a doorway in its north wall, and another and a narrow window on the west, and was apparently a cellar or storeroom.

Lay-Brothers' Frater

A skew-passage in the north-west angle of the cloister leads to the next chamber in the range. This was the lay-brothers’ frater, or dining-hall. Two of its trefoil-headed lancet windows survive in the west wall, and it is clear that there was one to each of the broad vaulted bays, the remains of four of which are to be seen.

The main drain runs underneath the frater, and on the north side of this is a twelfth-century doorway which formed part of the original lay-out of the abbey, and which was buried under the floor when the existing hall was built. The wall running across the frater is not its original north end, the exact location of which is now uncertain. It is possible that the northern end of the range may, as in the contemporary building at Beaulieu, Hampshire, have been used for the lay-brothers’ infirmary. After the middle of the fourteenth century the lay-brothers ceased to form an important part of the community, and the hall would have been put to other use. The lay-brothers’ dormitory was on the first floor.

Infirmary

The infirmary housed both the sick and the aged monks. Its buildings are reached through the passage at the north-east of the cloister. This passage leads to the smaller infirmary cloister, and at the east end of its south walk is the infirmary hall.

Infirmary Hall

The infirmary hall was built in the thirteenth, though its doorway was altered in the following, century. The hall is 107 ft long and 54 ft wide, and was divided into a nave and aisles by two rowsofclustered columns. The bases of two of the responds of the arcades remain in position on the north side at the west end, and on the south side at the east end; from these it is clear that the first bay at either end of the building was separated from the aisles by a wall as part of the original plan. The remains of a sill in the north wall show that the aisles were lit by pairs of lancet windows.

On the north side there is a large chamber which extends northwards for half its length beyond the line of the hall. The two doorways opening off the north aisle lead to the kitchens. At the west end, set at right angles to the hall, is a room with a drain at its north end, which must have been the infirmary reredorter.

In the fifteenth century the aisles were divided up into separate rooms each with its fireplace, and the arcades were apparently removed and replaced by walls.

A passage, formerly covered, and built in the fourteenth century over the foundations of earlier walls, leads directly from the infirmary hall to the church. It is unlikely that there was a separate infirmary chapel.

Informary Cloister

The infirmary cloister measures 84 ft by 71 ft. There is the base for a cistern in the south-west corner of the cloister garth. The remaining chambers round the cloister will next be briefly described, though the purpose to which they were all put is not known. On the north, entered through a doorway in the passage which separates it from the monks’ reredorter, is a room with a later fireplace inserted in its east wall. East of this is a larger chamber measuring 34 ft from north to south and 24 ft wide. It had an outward opening door to the cloister, and a window at the north end of its east wall. The north wall is of composite material, but the surviving double buttress at its north-west angle is original.

Infirmary Kitchen

To the east of this chamber was an open court beyond which is the infirmary kitchen. This was built in the early fifteenth century and must have replaced an earlier building. The fireplace is towards the north end of the east wall. The massive lintel rests broken in two in front of the hearth. Later in the century another kitchen, connected by a passage built out on the south, was added. This had great fireplaces in its east and west walls, and a door on the south led to the infirmary hall. On the north side is a scullery, to the north-east of which are the foundations of a fourteenth-century building which must have been demolished when the later kitchen was built.

Abbot's Lodging

To the north of the infirmary buildings lay the abbot’s lodging. This included the late thirteenth-century building running east and west which had the abbot’s camera, or living-room, on the first floor. A doorway on the south side of this room led into the abbot’s chapel, which was added in the following century. The chapel had a twolight east window, and there are the remains of a piscina in its south wall. In the fourteenth century also, a latrine building was built on to the east end of the abbot’s camera.

The site of the abbot’s hall was until recently covered by a cottage and its garden, which formed an enclave in the abbey area. This has now been cleared and the foundations of a series of rooms have been disclosed: these were evidently storerooms or cellars under the abbot’s hall. The hall was on the first floor and none of it survives. The building, which is on a grand scale with fine corner buttresses and good ashlar work to its numerous doorways, was built in the fourteenth century. South of the abbot’s hall there was another chamber on the north side of the court next to the infirmary kitchen.

To the south and east of the infirmary buildings was a garden whose walls still stand to a considerable height. Near the north-east end of this wall the relieving arch in the back wall of the cottage indicates the direction taken to the river by the main drain. Many fragments of carved stonework, dating from all periods in the abbey’s history and found in the course of clearance and excavation, can be seen in the lean-to sheds to the north of the monks’ frater.

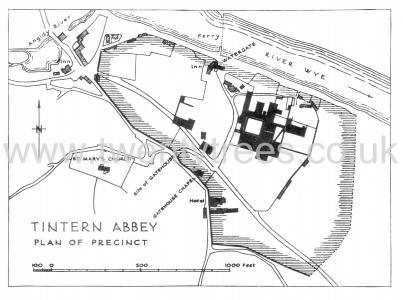

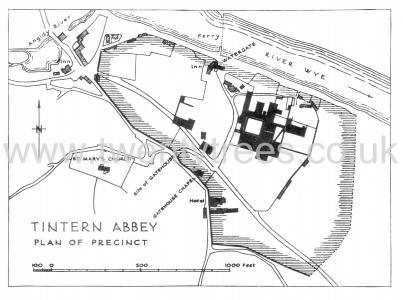

Precinct

As will be seen from the plan, the area originally occupied by the abbey was considerably larger than it is today; for the precinct wall, which surrounded the abbey buildings, enclosed 27 acres. The remains of this wall still exist on the south and west. It can be seen running diagonally across a field on the south side of the ChepstowMonmouth road. This road, which cuts through the precinct, was constructed about 1820. The wall then continues along the side of the lane behind the Beaufort Hotel, and the next house, St. Annes, incorporates the gatehouse chapel: its east window of three lancets still survives. The outer gatehouse must have been close by. The precinct wall continues along the lane, and returns to the river just east of the George Hotel.

To the west of the abbey church are the remains of a number of buildings whose foundations have been only partly exposed. They are believed to include the guest house, where visitors to the abbey would have lodged. To the north of these ruins, beside the Anchor Hotel, is a medieval gateway leading to the slipway of the old ferry across the Wye; the ferry continued in use until after the first World War. The precinct wall must bave continued along the river bank in both directions, and to the east the line of it can be seen running along the south side of the cart track.

The main abbey drain enters the claustral buildings near the porch through which visitors now go into the abbey. Water to flush this drain, and probably also to drive the abbey mill, was led from the little stream which still runs (except in dry weather) into the Angidy River, near the school. Visitors with time to explore can still see part of the old watercourse if they go three hundred yards up the footpath at the back of the school on the Raglan road.