Wessex from the Air Plates 2 and 3

Wessex from the Air Plates 2 and 3 is in Wessex from the Air.

Hambledon Hill [Map]. By Eric Gardner, M.B. (Cantab.), F.S.A.

Reference Nos. 244 and 245. County. Dorset. 14 NW. (130: D. 11). Parish. Child Okeford. Geological Formation. Upper Chalk. Time and Date of Photographs. About 7.0 p.m., 14th July.

Latitude. 500 54' 45" N. Longitude. 20 13' 13" W. Height of Aeroplane. 5,200 ft. (1,585 metres). Height above Sea-level. About 600 ft. (182 metro). Speed of Shutter. 1190th of a second.

For beauty of position and interest of detail the great camp on Hambledon Hill, six miles north-west of Blandford, is unsurpassed by any other earthwork in Dorset. A great isolated mass of chalk rises boldly out of the Stour Valley, and from its summit 600 ft. above sea-level three bold spurs diverge. One runs south and then turning east overhangs the village of Steepleton: another thrusts its great bulk eastward over the little hamlet of Shroton: while the third, girt with the mighty ramparts of the camp, at first runs north-west, and then swelling out into a broad promontory points northwards to where a little to the west the thin line of the Mendip Hills can be seen as a blue haze on the distant horizon. Immediately south of the Steepleton spur is another isolated chalk hill, a great squared mass whose flattened crest is crowned by the ramparts of Hod Hill Camp [Map].

At a very early date man discovered Hambledon to be an ideal situation for his primitive needs. From its summit he could safely watch an enemy climb its steep sides from the forest land filling the valley 300 ft. below. Its broad spurs would provide accommodation for his flocks, while east and west the open chalk land of Ranston Hill and Shillingstone Hill would give him a full view of the people, be they friends or foes, who lived there. To the south from the Steepleton spur he could overlook the whole summit of Hod. He lived there secure from surprise, and two long barrows and some flint flakes point to neolithic man as being the first of many who have left their traces on the hill-top: indeed, he may have built the earthwork now Ato be described, although this cannot be stated with any certainty in the absence of relics.

THE SMALL CAMP

On the dome-shaped summit of the hill, whence the three spurs diverge, can be traced the outlines of a very old circular camp. It is admirably shown on the air-photograph, and easily traced on the ground except on the north where time has nearly obliterated it on the steep hill-side. Its ramparts are very wasted and are mutilated by numerous cart tracks, so much so that it is impossible to be sure of the position of the original entrance, if it ever had one, for it may have been entered by a movable ladder, as the central area undoubtedly was at Clovelly Dykes in Devon.

In the plan the ramparts are shown diagrammatically without any gaps, but their true condition can be seen in the air-photograph. A good section shows them as rising 5 ft. out of their ditch and measuring about 30 ft. over all (sections D E).

As a defence against attack delivered from the flattened tops of the spurs double scarp-to-scarp ramparts are stretched across the bases of the spurs close to the camp; their profile is much the same as that of the camp itself except on the northern spur where they are much bolder, having been incorporated into the southern defences of the later and greater camp. A long barrow, alined nearly north and south (length 92 ft., breadth 41 ft., height 6 ft.), lies between the circular camp and the scarp-to-scarp defences on the Steepleton spur. A further defence is provided by another cross rampart farther down the Shroton spur, others can be seen near the point of the Steepleton spur, and probably if a careful search were made it would be found that all easy access to the spurs had been rendered difficult by scarping.

Just to the north of the circular camp and running from the eastern end of the scarp-to-scarp defences of the northern spur can be seen a faint bank (R), which makes its way straight down the deep hollow between the northern and Shroton spurs. Its faint outline would connect it in date with the circular camp, and it points down hill to where in a fold of the hill-side is a spring (s), always damp in summer, and which still flows as a winter bourn. The whole area of the circular camp has for many years been the site of extensive flint digging, and its pitted surface as seen in the air-photograph is a graphic record of this activity. No habitation sites can be detected now, and except for a few flint flakes and a scraper no relics are known to have been found there, though careful inquiry has been made of the workmen.

THE GREAT CAMP

The whole of the northern spur is defended by three tiers of ramparts enclosing an elongated area of about 25 acres, with entrances at the north, south-west, and south-east, respectively. It will be demonstrated by what can be seen on the ground and by the assistance given by the air-photograph that the camp was not built as it appears to-day, but was evolved from a smaller and simpler plan. It is the noting of differences in the construction of existing ramparts, tracing the fragmentary remains of others, examining the camp at different times of the day under the rays of the morning or evening sun, and so piecing the whole story together that make the study of Hambledon so fascinating.

It was first planned early in the days of hill camps before really great ramparts were used, when the defence was the steepness of the hill-side helped by scarping. Vulnerable points were specially strengthened, but everywhere the size and position of the ramparts were dictated by the requirements of the defence. In some camps, either later in time or the work of different peoples, the builders were more expert in the art of defence, and realized that the rampart itself could provide the best protection from the enemy.

It is instructive in this connexion to examine Payhembury Camp near Honiton, after seeing Hambledon, for there the defence of the great triangular promontory consists of three tiers of ramparts which are so vast that it was unnecessary to spare any thought on the vulnerability of any part of the hill. Viewed from the north-west corner the mighty ramparts compel an expression of wonder as they are seen precisely alined, cutting deep into the hill-side, regardless of the labour involved in their construction and providing in themselves a defence suffcient to meet all requirements.

If the Hambledon Camp be entered by the south-eastern gateway the area is found to rise everywhere above the ramparts, and immediately in front of the gateway, on the highest point Of this end of the camp, is a round barrow (indicated by the height-figure 623) from which a general survey can be made by walking northwards along the crest of the ridge.

The camp is divided by two cross ramparts into three areas: a southern, middle, and northern. The southern area, entered by two gates, is bounded on three sides by ramparts, and limited on the north by a rampart, here called the South Cross Rampart (H K), which suggests a mutilated rampart with a ditch on its south side; north of this is the central area narrowing into a high ridge, on the top of which a long barrow lying north and south forms a familiar landmark; northwards, again, the northern area, encircled by ramparts and rising to a height of 600 ft., swells out into a massive promontory, and is separated from the central area by a narrow wasted rampart (L M), the North Cross Rampart, which can be traced from one side of the camp to the other.

It appears from an examination of the earthworks that the small circular camp with its scarp-to-scarp ramparts is the earliest defensive work on the hill. The northern spur was fortified at a later date by building a camp that was limited on the south by the South Cross Rampart (HR) and divided by the North Cross Rampart (L M), the whole of the southernmost area being added very much later.

From a point near the round barrow it is interesting to note the sweep of the triple ramparts along the west side of the hill. As they pass northwards, instead of continuing at the level they occupy when they form the boundary of the southern and central areas, all three, at the junction of the northern and central areas, drop almost vertically a hundred feet down the hill-side, and continue at that lower level as they disappear from view round the northern end of the hill. By doing this they enclose a very much larger area at the northern end of the camp.

At this point it will be well to examine the western ramparts in some detail. Walking northwards from the south-western gate (T) the parapet of the inner rampart is seen to rise two to three feet above the sunken track on the edge of the area, which will be referred to as the Area Path; this is about 30 ft. wide and can be followed almost completely round the camp, but is indistinct on the south and south-east. To the right the area of the camp rises high above one, while from the parapet the rampart falls about 35 ft. into a ditch which has a parapet of about 4 ft. throughout its course. The second rampart falls about 25 ft. on to a flat shelf, below which the third rampart can be seen as a mere scarping of the hill-side, having a vertical height of about 20 ft.

The three main ramparts follow a somewhat meandering course to adapt themselves to the shape of the hill as they run from the south-western gate to the west end of the South Cross Rampart; but then they turn at a sharp angle and for some distance run absolutely straight, forming the boundary of the central area. At this angle the inner rampart is heightened and its parapet widened, and the middle rampart, whose parapet is also raised and widened, is drawn up to a great height, and measures no less than 40 ft. vertically and nearly 100 ft. on the slope. The outer rampart ignores the turn and continues past the angle in an unbroken curve. The heightening of the ramparts is explained by the acute turn they make at this point, for wherever a rampart turns sharply there is more soil available for its construction, which explains why rectangular camps are higher and wider at the corners than elsewhere.

It can easily be seen that such heightening is particularly advantageous at this angle on Hambledon for it both strengthens and steepens the defences at a vulnerable place, because the turn taken is determined by a fold in the hill-side and the approach is consequently a little less steep at this point. Further than this, the angle is important for it marks the junction where the older northern part of the camp is joined by a southern and more recent extension.

The outer rampart is thought to date from the time of this southern extension, and if this be a fact it explains why it sweeps so boldly past the angle and takes no part in it. Both the inner ramparts are heightened north of the long barrow, where they make another sharp turn, descend the hill, and then run round the head of the promontory; the inner one following the 500-ft. contour which until this point had been the level followed by the lowest. They all three then continue round the hill towards the north gate, but before reaching it the lowest dies out in a series of sheep runs, while the inner loses its parapet for some distance before the north gate is reached, but this parapet reappears close to the gate and forms one of its lateral defences.

All these little variations in the ramparts have been mentioned at some length because of their importance. It is probable that when by means of excavation more camps have been accurately dated it will be found that certain types of rampart are characteristic of the work of different peoples. Here at Hambledon a rampart was obtained by scarping the hill-side; but it was constantly being brought up to date, so to speak, and other ramparts were added by people who knew better how to build them. They were, however, always handicapped by having to conform more or less with the original plan, so that the final result—the wonderful camp that we see to-day—may after all have been awkward in shape and unsatisfactory and diffcult to defend. This may be the reason why a new and thoroughly up-to-date camp was built at the end of the first century B.C. on the neighbouring hill of Hod [Map].

Be this as it may, it is of great interest to study Hambledon, a primitive camp depending for its defence upon the natural difficulties of the hill-side, helped by scarping and later by the addition of big ramparts. How different it is to Winkelbury (Dorset), a primitive camp with no later additions: to Payhembury, whose mighty ramparts plough through the hill-side regardless of natural features and constitute in themselves the actual defence: to Castle Neroche, where the three great ramparts on the south side are constructed at enormous labour across an almost level piece of ground: and to those numerous camps, such as Whitsbury, Yarnbury, and Great Stockton, whose great ramparts hardly require the assistance of natural features to help the defence at all.

But to return to Hambledon. Unfortunately the north gate (N) is almost entirely destroyed by a chalk-pit that has deeply scarred the hill-side. Only a very steep and narrow path is left, winding round the outcurved end of the inner rampart on the east; but from an examination of existing remains it is probable that the path found its way to the bottom of the hill between the overlapping, outcurved, and swollen ends of the other ramparts.

Right at the bottom of the hill, best seen from the fields on the north, but broken into and destroyed by cultivation, are the remains of a semicircular platform which obviously had to be negotiated by any one seeking to enter by the path that ran up between the ramparts. This platform is reminiscent of that which forms an integral part of the interesting northern entrance of Sidbury (Devonshire).

The east side of Hambledon is even more interesting than the west. It does not form a continuous curve from the north gate to the south-eastern entrance, but is divided into three nearly equal portions, a central section and two flanks. The central section is gently curved inwards and the straight flanks are rather sharply bent back from it, and at their junction two rounded natural Buttresses run from the level of the area of the camp down tnem to its foot. They form noticeable features of the hill as seen from the Shroton spur (Plate II).

The three ramparts that constitute the defence on this side adapt themselves to these natural features. They are all slightly more accentuated as they cross the two Buttresses, so that the second and third have just been able to catch the slanting rays of the evening sun when the air-photograph was taken.

The inner rampart has a parapet as it approaches the north gate, as it crosses the Buttresses, and between the southern buttress and the south-eastern gate. The middle rampart has a parapet throughout its whole length which is heightened as it crosses the Buttresses, and it is on the Buttresses only that the outer rampart has any trace of a parapet.

At the foot of the hill close to the field hedge is a path which crosses the space between the Buttresses from north to south, and then runs obliquely up the hill to enter the outer ditch near the south-eastern gate (x): it is a well-defined ancient trackway and the only means of approach to that gate. Above it, in the lower part of its course, the hill-side is scarped, probably to prevent any attempt to reach the ramparts up the little combe between the Buttresses.

Two deep hollows run down the face of the inner rampart on this side of the camp and are features of considerable interest, for they mark the course of the ditches of the North and South Cross Ramparts through the inner rampart into its ditch, and prove that these transverse banks are not mere divisions of the area but are definite ramparts running right across the camp. The North Cross Rampart is very wasted now and can only be traced with difficulty, but a very definite ridge across the Area Path on the east shows that formerly it ran right up the inner rampart on this side. The line of its ditch through the inner rampart is clearly shown in the air-photograph as a deep hollow which can be traced on the ground immediately south of a small but conspicuous thorn tree growing on the crest of the main rampart.

The ditch of the South Cross Rampart on the east is also plainly traceable, as it cuts through the parapet of the inner rampart leaving a well-defined notch, and then ploughs its way down the face of the rampart to reach the ditch. When this rampart was being built the ditch of the South Cross Rampart had to be filled up: its filling has settled and has left the notch in the parapet and the scar down the face of the rampart. Some of the filling, however, fell into the main ditch, was cleared up, and piled on to the middle rampart, heightening and widening its parapet at this point into a very definite little platform.

If an observer stand in the area and look towards the inner rampart, the notch in its parapet will be seen as a very noticeable feature, and on each side of it, that is on the north and south, the parapet is raised into two very definite prominences of which the northern is the larger. For some time these were rather difficult to explain, until it was realized that the South Cross Rampart itself is really the old basal rampart of the original camp on the northern spur, and therefore if the notch in the parapet represent its ditch, the prominence to the north of it marks the line of the old rampart itself and that on the south marks the parapet on the outer lip of its ditch.

It is just possible that the little platform on the middle rampart was used for observation purposes, for it is only from its summit that a view of the path ascending the hill to reach the south-eastern gate can be obtained.

The southern defences of the camp consist of the inner and middle ramparts which sweep round from the south-western gate across the narrow ridge that joins the northern spur to the dome-shaped summit of the hill, and then turn north to reach the south-eastern gate. Near the south-western gate the inner rampart has a high parapet which soon fades out altogether, but it reappears, and continues about 3 ft. in height to the western edge of the ridge. As it crosses the ridge it is raised to a height of 20 ft. above the area of the camp, and falls no less than 30 ft. into its ditch outside. Depressions at the edge of the area show clearly where the soil was obtained to build it, and it forms one of the most impressive features of the camp as it stands out, gaunt and slender, towering above the steep combes that flank it, a mark against the sky for many miles. East of the ridge the rampart turns north and continues towards the south-eastern gate, swelling out and curving inwards as it reaches it. The middle rampart conforms to the one just described, but across the ridge it has been mutilated to provide material for the modern path to the south-eastern gate, and east of the ridge as it runs northward it has been nearly levelled for the same purpose.

Outside this second rampart on the ridge is a berm of about 100 ft., which is succeeded by two scarp-to-scarp ramparts which are the enlarged representatives of the other scarp-to-scarp defences across the necks of the Shroton and Steepleton spurs.

A modern path to the south-eastern gate has been cut through both these scarp-to-scarp ramparts, completely detaching their eastern ends: it is flanked on its passage to the gate by the lowered middle rampart on the left and by a slight bank which is all that is left of the outer rampart on the right. Outside these remains of the outer rampart some further scarping is visible on the edge of the combe, but all ancient features have been obscured in this' region by the construction of the path and consequent mutilation.

It is very doubtful if there were ever any means of entering the south-eastern gate from the direction of the dome on the top of the hill. There is no sign in the air-photograph of an ancient track pointing towards it, and the only means of access seems to have been by the oblique path that climbs the hill from the bases of the two great Buttresses. After all, it was only a very narrow entrance between the swollen and incurved ends of the inner rampart. The important gate at this end of the camp was the south-western entrance (T), which will be seen to be a replica (reversed) of the north-eastern gate of the neighbouring camp on Hod Hill. As it pierces the main defences it is flanked by the massive, incurving ends of the inner rampart, and then by the swollen ends of the middle rampart, while beyond that it is covered by a curtain formed by the third rampart, and a prolongation of the middle which sweeps round and defends it, so that a forced entry would be a matter of extreme difficulty. Half-way down the hill a steep scarp (w) has been made to give further protection to the gate against attack from the west.

The air-photograph gives a very clear indication of the main approach to this entrance. A well-defined track runs northwards, cutting through the scarp-to-scarp ramparts on the Steepleton spur, thus proving that they are older than the track, and then passing west of the circular camp it runs along the edge of the combe incorporated in a modern cart-track under, and exposed to attack from, the whole length of the southern defences. It then turns to enter the gateway, and passes between a knob-like promontory on the enfolding rampart on the left and a small square platform cut in the side of the middle rampart on the right. Should an enemy succeed in passing the southern ramparts he would still have to negotiate this narrow entry, thronged on both sides by the defenders ofthe camp, and after that converging ramparts would lead him to the inner gate set in the midst of the main defences. The entrances of many prehistoric camps are interesting, but few show such subtle ingenuity as this south-western gate of Hambledon.

It is most remarkable that the ancient track leading to the south-western gate, shown so clearly on the air-photograph, should at midday be absolutely invisible and untraceable on the ground; but gradually, as evening approaches, an observer resting on the southern rampart will see its whole line and course mysteriously emerge, take form, and rise into view as the setting sun strikes it with his slanting rays.

If such observer now turn and look northwards he will see a new picture. The whole area of the camp is dotted with the outlines of pits and banks never before suspected, and the North Cross Rampart rises up as a feature of considerable proportions. Hambledon is a wonderful place: no one visit will reveal all there is to see, for every hour of the day has its special revelation. Each will show something new according to the position of the sun. The air-photograph has confirmed all that has been noted, has amplified a good deal more, and has shown clearly what had previously been only matters of surmise.

Throughout the camp the area rises above the ramparts like the crown of a hat above its brim, but especially at the northern end where it stands 100 ft. above its defences. The northern area of the camp is studded with circular depressions marking the sites of pits; it is bounded east and west by the triple ramparts, and is entered at the north by the mutilated northern gate (N). On the south it is limited by the North Cross Rampart, which is more easily traced on the west than on the east.

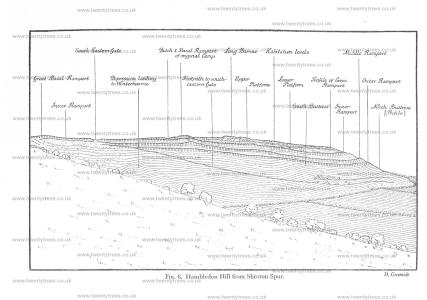

The central area, bounded on the north by the North Cross Rampart and on the south by the South Cross Rampart is of particular interest. On the west, where it is bounded by the three main ramparts, it calls for no comment, but on the east it is divided into several tiers which should be examined not only on the ground but from the Shroton spur, from which a good general view can be obtained (Fig. 6).

On the extreme eastern edge of the central area is the great inner rampart, which is almost devoid of any parapet, though a slight tilt in the ground gives the appearance of one in the air-photograph. Immediately inside the rampart, and running the whole length of the area, the Area Path has been elaborated into a bold flat platform, 32 ft. wide, which for convenience of reference has been called the Lower Platform. Above it, on the top of a scarp, 25 ft. high, is another platform, the Upper Platform, which also runs from one end of the central area to the other: it, too, is about 32 ft. wide. Above this the hill-side slopes gently to the summit, and is more or less divided into two tiers; both these tiers are covered with the outlines Of rectangular pits of varying size but measuring roughly 15 to 19 ft. across. Above this habitation level is the ridge of the hill, on which lies a long barrow (208 ft. long, 55 ft. wide, and 11 ft. high) pointing NNE. and SSW.

The southern area, bounded on the north by the South Cross Rampart and elsewhere by the main ramparts of the camp, has but few features of interest. It is entered by the south-eastern and south-western gateways, a round barrow stands on its highest point, and only two or three pits can be seen. A well-defined track (see air-photograph) runs northward from the south-western gate past the west end of the South Cross Rampart to reach the ridge in front of the long barrow, and continues north between a line of circular pits on the west and a similar line of rectangular pits on the east: it appears to end at the North Cross Rampart, but it may have continued over it. In the latter part Of its course it is somewhat reminiscent of the mid street described by General Pitt-Rivers as running down the centre of the northern area of Winkelbury.

The South Cross Rampart forms the southern boundary and completes what is thought by the writer to be an old, and probably the original, camp on the northern spur. Entrance was obtained to this camp by means of a gate placed at the west end of the South Cross Rampart, for no trace of a continuation of its ditch can be found cutting the main rampart on the west. Many triangular camps on promontories have lateral basal entrances, such as Hawksdown and Muzbury near Axmouth, Pilsdon Pen, and Eggardon; at Buckland Rings the basal entrance is central.

The defences of this older camp probably consisted of a rampart which ran down into a ditch, below which the hill-side was scarped. In the middle of the west side of the camp rabbits have burrowed into what is now the middle rampart and have penetrated into what must be the bottom of the ditch of the inner rampart; their scrapes contain many pottery fragments of a particular character, similar to that which has been found elsewhere in the camp at a place shortly to be described.

This primitive camp was divided into two parts by the North Cross Rampart, which in size— 35 ft. over-all measurement across its ditch and rampart—is comparable with the cross rampart of Winkelbury (Dorset), where the over-all measurement is the same although its profile is bolder: moreover, both the cross ramparts resemble each other in that their ditches communicate with the main ditch of the camp on one side only.

Winkelbury [Map] is an interesting camp built on a chalk spur projecting northwards over the village of Berwick St. John. It is divided into two parts by a cross rampart, its northern area is dotted with pits, and the highest part of the area is over 100 ft. above an encircling rampart which has in many places slipped and foundered into its ditch below. It is convenient to compare Hambledon with Winkelbury, for Winkelbury was excavated by General Pitt-Rivers (Excavations in Cranborne Chase, ii), and his conclusions may be briefly summarized.

He found a good deal of pottery of various types, all of which he considered to be contemporary and pre-Roman; one type was new to him. All the pottery was distributed over the area of the camp and under the rampart: whoever built the camp must have been responsible for the pottery, for no relics pointing to a later date were found except a few fragments of Romano-British pottery which were admitted to be without significance. It is possible to look upon Winkelbury as built as a whole and not reconstructed afterwards.

Although Pitt-Rivers was unable to identify some of the pottery he found at Winkelbury, it is now known that it is comparable with that discovered by Captain and Mrs. Cunnington at All Cannings Cross and assigned by them to the transition period when the culture of the Early Iron Age was beginning to replace that of the Bronze Age, and its date in Wiltshire is about 500 B.C. Mrs. Cunnington, commenting on the pottery from Winkelbury, says: 'All the Pottery from Winkelbury illustrated in Plate CLVIII (Excavations in Cranborne Chase, ii) with the exception of Figs. 7 and 10, Romano-British wares, might have come from All Cannings Cross' (All Cannings Cross, p. 198).

Plates II and III HAMBLEDON HILL

The evidence at Hambledon is much the same: a hill-top camp divided into two by a cross rampart of low profile, with an area 100 ft. above its defences which consist ofa rampart formed by scarping a steep hill-side, running down into a ditch, below the hill was probably scarped at vulnerable points. The pottery already stated to have been found in the rabbit scrapes on the west of the hill is typical All Cannings Cross ware and the same as that found at Winkelbury.

But another and more important site where pottery has been found is at the north end of the camp. It will be remembered that as the inner rampart approaches the west side of the northern gate a slight parapet appears on its lip just on the edge of the Area Path, adjacent to the gate. Children from all the villages round Hambledon spend many happy hours every summer evening toboganning down the ramparts on sacks, trays, and planks of wood, and the northern slopes provide a specially good run for this amusement. In clambering up the steep face of the inner rampart they have worn a deep path right through the parapet about 2 yds. west of the chalk-pit: this has been worn deeper year by year by the winter rains, so that now a clear section has been cut from the Area Path through the parapet and down the face of the rampart. Deep in this section, lying under the parapet, is a thick layer of pottery and char- coal: in other words, the parapet has been raised on an old cooking-place, and all the pottery found in it is All Cannings Cross ware and can be assigned to the Early Iron Age.

The manner in which this pottery came to lie where it does is fairly obvious. Hambledon is a vast place and must have taken a long time to build, and it is probably not straining the imagination too far to picture the Early Iron Age people of the Halstatt period as living on the hill, possibly before, but certainly during, the building. There would undoubtedly be a strong force living on the Area Path at the north end of the camp round about the north gate, and their cooking-fires would be made on the ground. The parapet of the inner rampart on the west of the gate is an integral part of the gate, and when it was raised it covered the pottery and hearths then lying on the ground: the main gateway, and consequently the camp to which it gave entrance, cannot possibly be of earlier date than the pottery found under the parapet. That is to say, it was not built before the beginning of the Early Iron Age and probably actually dates from that time.

The outline of the northern end of the camp with its area rising high above the ramparts has given rise to the suggestion that its defences in the Early Iron Age were alined on an even earlier plan, but there is not sufficient evidence at the present time to support this. Well-worked flint scrapers are numerous at the north end, but they are even more numerous at Winkelbury. It should be noted that Pitt-Rivers found absolutely nothing to cause him to assign Winkelbury to an earlier date than that indicated by the All Cannings Cross pottery. If the two camps are comparable, as they appear to be, there seems no reason to claim for Hambledon a date earlier than the beginning of the Early Iron Age, about 500 B.C.

The northern and middle areas together formed a complete camp which probably served the needs of its builders for some considerable time, but, as the years passed, alterations were made to the original plan, and the southern area of the spur was included in the circle of its ramparts. It seems reasonable to suppose that the second rampart of the older camp was then altered to conform to the new middle rampart of the southern extension: a walk round the camp shows how uniform this middle rampart is throughout its course. The third and lowest rampart is also thought to belong to this period of southern extension, for reasons already given.

But the most important evidence of the date of the southern extension is that given by the ramparts themselves, and especially by the south-western gate. That gate is built on a definite and complicated plan identical with that of the north-eastern gate of Hod Hill which lies across the valley on the south: whoever built the one must have built the other. Hod Hill was excavated by Professor Boyd Dawkins in 1897 (Archaeological Journal, vol. Ivii), and from these excavations we learn that in the north-west corner of the camp, inside pre-existing ramparts, a Roman fort was constructed in the early days of the Claudian conquest; the main ramparts are therefore pre-Roman, and from the evidence of numerous relics found inside these ramparts in the shape of human bones, pottery, coins, ornaments, and implements it is possible to 'point out unmistakably that it' (i.e. the camp) 'belongs to the later portion of the prehistoric Iron Age, immediately before the Roman Conquest'.

The story of Hambledon Hill seems, then, to be briefly as follows: Neolithic man buried his dead in two long barrows on the hill-top, and may have constructed the circular camp with its outlying defences at the intersection of the three spurs, but it must be admitted that at present it is not possible to identify a neolithic camp by its construction alone. Knap Hill Camp, excavated by Mrs. Cunnington, and Windmill Hill Camp, Avebury, now being excavated by Mr. A. Keiller (age 38), have both been proved to be neolithic, but whether their defences, which are entered by numerous causeways crossing their encircling ditch, represent the only type of stronghold made in neolithic times is not yet known. However, the circular camp at Hambledon if not neolithic is certainly older than the great camp on the northern spur, for one of its outlying defences has been incorporated with the defences of that camp, and another is crossed by the trackway leading to its principal gate.

The camp on the northern spur was built at different times, the earlier northern portion dating from about 500 b.c., while the southern ramparts were not added until late in the first century B.c. and possibly not until the early years of the first century of the present era.

The principal features of the earthworks on Hambledon Hill have now been discussed in some detail, and certain conclusions have been reached, but no description of a camp can be considered final which is not based on careful excavation, and the major secrets of Hambledon still lie beneath its unopened ramparts. However, it is sometimes permissible to peep between the uncut pages of a book and so glean some idea of its contents, and that is what has been done here. Information has been wrung from pottery fragments found in a fortuitous section and in many rabbit scrapes, ramparts have been traced, and half-obliterated banks and ditches, trackways and pits have been dragged from semi-obscurity by means of aerial photography and made to tell their tale: so the whole story has been built up. No final conclusions have been reached, and care has been taken to infer nothing that is incapable of demonstration.

LITERARY REFERENCES

The references to Hambledon are, for the most part, short and of little value. The first reliable description is that by Mr. Heywood Sumner.

C. Warne, Ancient Dorset, 1872, p. 325 (note).

E. Cunnington, 'Hambledon Hill, Dorset', Proc. Dorset Field Club, 1895, xvi. 156—7.

Heywood Sumner, Earthworks of Cranborne Chase, 1913, 15—17, Plate II.