Adytum

Adytum is in General Words.

Adytum. The innermost sanctuary of an ancient Greek temple.

Avebury by William Stukeley. The centers of these two double circles are 300 cubits asunder. Their circumferences or outward circles are 50 cubits asunder, in the nearest part. By which means they least embarrass each other, and leave the freest space about 'em, within the great circular portico (as we may call it) inclosing the whole; which we described in the former chapter. There is no other difference between these two temples (properly) which I could discover, save that one, the southermost, has a central obelisc, which was the kibla, whereto they turned their faces, in the religious offices there performed: the other has that immense work in the center, which the old Britons call a cove [Map]: consisting of three stones placed with an obtuse angle toward each other, and as it were, upon an ark of a circle, like the great half-round at the east end of some old cathedrals: or like the upper end of the cell at Stonehenge [Map]; being of the same use and intent, the adytum of this temple. This I have often times admired and been astonished at its extravagant magnitude and majesty. It stands in the yard belonging to the inn. King Charles II. in his progress this way, rode into the yard, on purpose to view it.

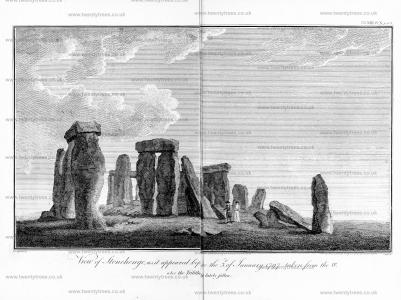

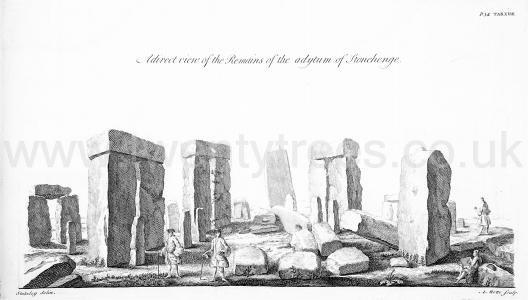

Stonehenge by William Stukeley. Many drawings have been made and publish'd, of Stonehenge . But they are not done in a Scientific way, so as may prove any point, or improve our undemanding in the work. I have therefore drawn four architeutonic orthographies: one, Tab. XII. is of the front and outside: three are different sections upon the two principal diameters of the work. These will for ever preserve the memory of the thing, when the ruins even of these ruins are perish'd; because from them and the ground-plot, at any time, an exact model may be made. Tab. XIV, XV, XVI. these orthographies show the primary intent of the founders; they are the designs, which the Druids made, before they put the work in execution. And by comparing them with the drawings correspondent, of the ruins, we gain a just idea of the place, when it was in its perfection. But now as we are going to enter into the building, it will be proper again to survey the ground-plot, Tab. XI. which is so different from that publifh'd by Mr .Webb. Instead of an imaginary hexagon, we see a most noble and beautiful ellipsis, which composes the cell, as he names it, I think adytum a proper word. There is nothing like it, to my knowledge, in all antiquity; and 'tis an original invention of our Druids, an ingenious contrivance to relax the inner and more sacred part, where they perform'd their religious offices. The two outward circles do not hinder the sight, but add much to the solemnity of the place and the duties, by the crebrity and variety of their intervals. They that were within, when it was in perfection, would see a most notable effect produc'd by this elliptical figure, included in a circular corona having a large hemisphere of the heavens for its covering.

Stonehenge by William Stukeley. Somewhat more than 8 feet inward, from the inside of this exterior circle, is another circle of much lesser stones. In the measure of the Druids 'tis five cubits. This circle was made by a radius of 24 cubits, drawn from the common centers of the work. This struck in the chalk the line of the circumference wherein they set these stones. The stones that compose it are 40 in number, forming with the outward circle (as it were) a circular portico: a most beautiful walk, and of a pretty effect. Somewhat of the beauty of it may been in Plate XVII. where, at present. 'tis most perfect. We are impos'd on, in Mr. Webb 's scheme, where he places only 30 stones equal to the number of the outer circle, the better to humour his fancy of the dipteric aspect, p. 76. He is for persuading us, this is a Roman work compos'd from a mixture of the plainness and solidness of the Tuscan order, with the delicacy of the Corinthian. That in aspect 'tis dipteros hypcethros, that in manner 'tis pycnostylos; which when apply'd to our antiquity, is no better than playing with words. For suppose this inner circle consisted of only 30 stones, and they set as in his scheme, upon the same radius , as those of the outer: what conformity has this to a portico properly, to an order, tuscan, Corinthian or any other, what similitude is there between these stones and a column ? where one sort is square oblong, the other opposite (by his own account) pyramidal. Of what order is a column, or rather a pilaster, where its height is little more than twice its diameter? Where is the base, the shaft, the capital, or any thing that belongs to a pillar, pillaster or portico? the truth and fact is this. The inner circle has 40 stones in it. Whence few or none but those two intervals upon the principal diameter, happen precisely to correspond with those of the outer circle. Whereby a much better effect is produc'd, than if the case had been as Webb would have it. For a regularity there, would have been trifling and impertinent. Again, Mr. Webb makes these stones pyramidal in Shape, without reason. They are truly flat parallelograms, as those of the outer circle. He says, p. 59. they are one foot and a half in breadth, but they are twice as much. Their general and designed proportion is 2 cubits, or two cubits and a half, as they happen'd to find suitable Stones. A radius of 23 cubits strikes the inner circumference: of 24 the outer. They are, as we said before, a cubit thick, and 4 cubits and a half in height, which is above 7 foot. This was their stated proportion, being every way the half of the outer uprights. Such seems to have been the original purpose of the founders, tho' 'tis not very precise, neither in design, nor execution. In some places, the stones are broader than the intervals, in some otherwise: so that in the ground-plot I chose to mark them as equal, each 2 cubits and a half. There are scarce any of these intire, as to all these dimensions; but from all, and from the symmetry of these Celtic kind of works, which I have been conversant in, I found this to be the intention of the authors. 'Tis easy for any one to satisfy themselves, they never were pyramidal; for behind the upper end of the adytum there are three or four left, much broader than thick, above twice; and not the lead semblance of a pyramid. I doubt not but he means an obelisk, to which they might some of them possibly be likened, but not at all to a pyramid. Nor indeed do I imagine any thing of an obelisk was in the founders view; but the stones diminish a little upward, as common reason dictates they ought to do. Nor need we bestow the pompous words of either pyramid, or obelisk upon them. For they cannot be said to imitate, either one or other, in shape, use, much less magnitude: the chief thing to be regarded, in a comparison of this sort. The central distance between these stones of the inner circle, measured upon their outward circumference, is 4 cubits. I observe further, that the two stones of the principal entrance of this circle, correspondent to that of the outer circle, are broader and taller, and set at a greater distance from each other, being rather more than that of the principal entrance in the outer circle. It is evident too, that they are set somewhat more inward than the rest; so as that their outward face stands on the line that marks the inner circumference of the inner circle. I know no reason for all this, unless it be, that the outside of these two stones, is the outside of the hither end of the ellipsis of the adytum: for so it corresponds by measure upon the ground-plot. This is apparent, that they eminently point out the principal entrance of that circle, which is also the entrance into the adytum. For five stones on this hand, and five on that, are as it were the cancelli between the sanctum and sanctum sanctorum, if we may use such expressions. 'Tis scarce worth mentioning to the reader, that there never were any imposts over the heads of these stones of the inner circle. They are sufficiently fasten'd into the ground. Such would have been no security to them, no ornament. They are of a harder kind of stone than the rest, as they are lesser; the better to resist violence.

Stonehenge by William Stukeley. Table XVIII. A direct view of the Remains of the adytum of Stonehenge.

Archaeologia Volume 13 Section IX. Dear Sir,

Having lately had more leisure to make remarks on the alteration produced in the aspect of Stonehenge, by the fall of some of the stones in January last, than when I first visited the spot for this purpose, I am anxious to lay before the Antiquarian Society a more full and correct account of it than that which you did me the honour to transmit to them before.

On the third of the month already mentioned some people employed at the plough, full half a mile distant from Stonehenge suddenly felt a considerable concussion, or jarring, of the ground, occasioned, as they afterwards perceived, by the fall of two of the large stones and their impost. That the concussion should have been so sensible will not appear incredible when I state the weight of these stones; but it may be proper to mention, first, what part of the struture they composed, and what were their respective dimensions.

Of those five sets, or compages, of stones each consisting of two uprights and an impost which Dr. Stukely expressively termed trilithons, three had hitherto remained in their original position and entire, two being on the left hand side as you advance from the entrance towards the altar-stone, and one on the right. The last mentioned trilithon [a] is now levelled with the ground. It fell outwards, nearly in a western direction, the impost in its fall linking against one of the stones of the outer circle, which, however, has not been thereby driven very considerably out of its perpendicularity. The lower ends of the two uprights, or supporters, being now exposed to view, we are enabled to ascertain the form into which they were hewn. They are not right-angled, but bevilled off in such a manner that the stone which stood nearest to the upper part of the adytum is 22 feet in length on one side, and not quite 20 on the other; the difference between the corresponding sides of the fellow-supporter is still greater, one being as much as 23, and the other scarcely 19 feet, in length. The breadth of each is (at a medium) 7 feet 9 inches, and the thickness 3 feet. The impost, which is a perfect parallelopipedon, measures 16 feet in length, 4 feet 6 inches in breadth, and 2 feet 6 inches in thickness.

Note a. Marked [Black Letter Lowercase H] in Smith's Choir-G-aur. This tnlithon might, with great propriety, he caiied the weftern, as no one of the others food more nearly wef of the center of the ltrudlure.