Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

A Sentimental Guide to Stonehenge by Lady Antrobus is in Books.

Priceless Stonehenge—Some Impressions.

(From Ladies' Realm Magazine.)

The Great Druidical Temple, or (as some hold) Phœnician Observatory, composed of gigantic, beautifully-coloured, hewn stones, stands in the middle of Salisbury Plain. These stones have been measured, counted, defaced, praised, depreciated, commented upon, by numerous authorities on countless occasions, but (to my knowledge) no account of their poetical and picturesque aspects, at different seasons of the year, has been attempted. I shall feel satisfied if I succeed in conveying feebly in words what David Cox (the artist) did ably in colours, with his glowing brush. I do not propose to enter into any statistics, as to the "Market value of Stonehenge to the nation," or to tell you the number of miles that lie between it and the town of Salisbury, the goodness or inferiority of the roads to it, the number of visiting tourists, &c.; I only wish to place before you some impressions I have felt of its grandeur and charm, through many seasons, in all sorts of weather, and varying moods.

There is always a constant surprise and delight to me in the manner in which Stonehenge bursts upon one, approach it as one may, from various points across the undulating Plain which surrounds it. Starting upon one's "Pilgrim's Path" to visit it, from any side, at first there is nothing to be seen but the crisp crackling grass underfoot, and the white glittering roads; then, as one advances nearer, unexpectedly, dark, mysterious forms seem to start up, which gradually shape themselves into the incompleted circle we call "Stonehenge."

The late spring, and early summer, are enchanting periods; myriads of starry white flowers, and gorgeous yellow and blue ones, wave together with a glowing harmony of colour, as they are swayed by soft breezes, whilst a "Hallelujah Chorus" of skylarks sing overhead, making the air full of scent and sound. In this setting, the old stones seem all yellow and grey in the brilliant sunshine. Picturesque shepherds, wrapped in their great dark-blue cloaks, appear upon the horizon; tinkling sheep bells are heard, reminding one of the Roman Campagna; evening falling, brings a sense of peace and stillness, chimes from the old Church at Amesbury float across the valley. The light comes and goes, and the world seems far away.

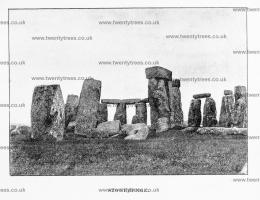

Photos.

To my mind the magic of Stonehenge is never more powerfully felt than during the wild, tempestuous autumnal gales, that usually sweep across the Plain in October. Great clouds roll above, enfolding the circle in a shadowy purple mantle, sometimes tipped with gold. Thoughts rise up suddenly, of the many tragedies, feasts, sacrifices, mysterious rites that must have been enacted here in far-off bygone days. One wonders if beautiful golden-haired Guinevere passed this way, on her flight to safety, at the Convent at "Ambresbury" (the Land of Ambrosius), or if sad King Arthur tarried there on his lonely homeward journey?

I prefer to picture to myself, Stonehenge, in happy, thoughtless Pagan days, Druid priests and priestesses forming grand processions; crossing the "rushing Avon" and winding up from the valley to Stonehenge, clothed in pure white, and holding gleaming sickles in their hands, chanting hymns on their way to perform the sacred rite of cutting the mistletoe. Perhaps they sang and chanted through the short summer night, waiting for the sun to rise (over the pointed outlying stone) on the day which marks the solar half-year (June 21st), and which bathes the altar-stone in golden light. Probably this was the signal for sacrifice, the death of the victim, and the appeasing of wrathful gods. In mid-winter the stones appear like black masses, in the midst of driving snows. The least interesting time of year, in this enchanted place, is the bright, clear, commonplace summer, when no mysteries abound (except by moonlight). The old gods are sleeping, everything is orderly, agriculture and its implements surround us, and Romance seems dead for the moment. Farewell.

Florence Caroline Mathilde Antrobus.

In approaching' the momentous and deeply interesting subject of Stonehenge, I considered it best and wisest to collect the thoughts and opinions of several learned authors on this subject, and submit them to the reader, who thus will have an opportunity of comparing for himself the truth and merits of the different theories presented to him for judgment.

Various explanations of the name "Stonehenge" have been forthcoming; but the true etymological significance seems to be: A.S. "Stàn," used as an adjective, and "henge," from A.S. "hòn" i.e., stone hanging-places, from the groups of stones resembling a gallows. This was long ago suggested by Wace, the Anglo-Norman poet, who writes:—

"Stanhengues ont nom en Englois [Stonehenge is the name in English]

Pierres pendues en François." [Hanging stones in French]

As to the date of Stonehenge, opinions vary. It is supposed Hecatæus (500 B.C.) mentioned it as the "Round p. 22Temple" (Translation of Extract from Diodorus Siculus, about B.C. 8).

Hecatæus, the Milesian, and others, have handed down to us the following story:—"Over against Gaul, in the great ocean stream, is an island not less in extent than Sicily, stretching towards the north. The inhabitants are called Hyperboreans, because their abode is more remote from us than that wind we call Boreas. It is said that the soil is very rich and fruitful, and the climate so favourable that there are two harvests in every year. Their fables say that Latona was born in this island, and on that account they worship Apollo (Apollo would signify the sun to the Latins) before all other divinities, and celebrate his praise in daily hymns, conferring the highest honours upon their bards, as being his priests. There is in this island a magnificent temple to this god, circular in form, and adorned with many splendid offerings. And there is also a city sacred to Apollo, inhabited principally by harpers, who in his temple sing sacred verses to the god, accompanied by the harp, in honour of his deeds.

"The language of the Hyperboreans is peculiar, and they are singularly well affected towards the Greeks, and have been so from the most remote times, especially to those of Athens and Delos. It is even said that some Greeks have travelled thither, and presented offerings at their temple inscribed with Grecian characters. They also say that Abaris in former times went thence to Greece, to renew their ancient friendship with the Delians. It is related, moreover, that in this island the moon appears but a short way from the earth, and to have little hills upon it. Once in nineteen years (and this period is what we call the Great Year) they say that their god visits the island; and from the Vernal Equinox to the rising of the Pleiades, all the night through, expresses his satisfaction at his own exploits by dances and by playing on the harp.

"Both the City and the Temple are presided over by the Boreadœ, the descendants of Boreas, and they hand down the power in regular succession in their family."

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

The first author who is considered to make unmistakable mention of Stonehenge is Henry of Huntingdon (twelfth century). In his Chronicle he speaks of it as the second wonder of England, and calls it Stanenges. Geoffrey of Monmouth (1138) wrote of it about the same time; he believed it to have been erected by Aurelius Ambrosius, King of Britain, and called it Hengist's Stones. Giraldus Cambrensis, a contemporary of Geoffrey, also makes mention of it.

Among more modern authors, may be quoted Sir Philip Sidney's lines:—

"Near Wilton sweet, huge heaps of stones are found,

But so confused that neither any eye

Can count them first, nor reason try

What force them brought to so unlikely ground."

Then Wharton's sonnet:—

"Thou noblest monument [Historic Stonehenge] of Albion's isle!

Whether by Merlin's aid from Scythia's shore

To Amber's fatal plain Pendragon bore,

Huge frame of giant hands, the mighty pile,

To entomb his Britain's slain by Hengist's guile;

Or Druid priests, sprinkled with human gore,

Taught 'mid thy massy maze their mystic lore;

Or Danish chiefs, enriched with savage spoil,

To victory's idle vast, an unhewn shrine,

Reared the rude heap; or in thy hallowed round

Repose the kings of Brutus' genuine line;

Or here those kings in solemn state were crowned

Studious to trace thy wondrous origin,

We muse on many an ancient tale renowned."

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

To descend to prose. Langtoft, in his Chronicle, says:—"A wander wit of Wiltshire, rambling to Rome, to gaze at antiquities, and there screwing himself into the company of antiquarians, they entreated him to illustrate unto them that famous monument in his country called Stonage. His answer was that he had never seen it. Whereupon they kicked him out of doors, and bade him go home and see Stonage."

The immortal Pepys says the stones are "as prodigious as any tales I have ever heard of them, and worth going this journey to see."

The archæologist, Mr. Edmund Story Maskelyne, fixes the date of Stonehenge at 900 or 1000 B.C. I quote what he says from a lecture, read 1897, "On the Age and Purpose of Stonehenge":—

"It is of consequence that we should recognize that Stonehenge was built about nine or ten hundred years B.C., and not 700 A.D., as many writers would have us believe. For instance, Dr. W. M. Flinders Petrie, in his book, ‘Stonehenge, 1880,' states his opinion that it was erected A.D. 700±200, that is, between A.D. 500 and 900. The date of Stonehenge will be of great interest if there is found at Avebury remains sufficiently perfect to determine astronomically the date when that monument was erected. For it cannot be but interesting to ascertain when the two cults—that of the sun, pure and simple, as exemplified in the original Temple at Stonehenge; and the cult of the sun in connexion with the serpent, as exhibited at Avebury—respectively prevailed in this country."

Mr. Story Maskelyne's reasons for his theory that Stonehenge was built by the Phœnicians are as follows:—

"I should like to add some reasons for my belief that Stonehenge was built by the Phœnicians. In the first place, I cannot think of any other people that could have either designed or executed such a monument, which required both science for its conception and skill for its erection. The Phœnicians, with their perfect familiarity with masts, and cordage, and pulleys, could easily lift the imposts, of which the largest—being about 11 ft. long, 4 or 6 wide, and 3 ft. thick—would weigh less than ten tons; and the Phœnicians must have known how the Egyptians raised masses of stone many times heavier.

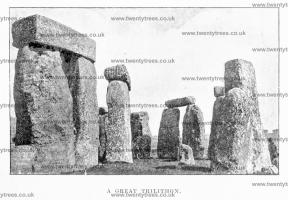

"The trilithon standing clear seems to have had some fascination for these people. They are found still standing in Tripoli in Libya, as described in ‘The Hill of the Graces,' a record of investigation among the Trilithons and Megalithic sites of Tripoli by Mr. Cowper, F.S.A., 1897, and specimens exist on the Continent of Europe, in Normandy and in Brittany. One may be seen in the Island of Ushant, and another in St. Nazaire on the probable route they adopted for the passage of tin.

"Another peculiarity can be seen to this day by any one at Stonehenge in the large trilithon impost, namely, that the under surfaces of the imposts which rested on the uprights are smoothly cut and slightly bevelled, so as to throw the principal weight of the mass of the impost on its outside edge, thus excluding rain, &c., and this very contrivance was employed by the Egyptians in the pyramids, and it is certain that the Phœnicians had free intercourse with Egypt. Finally, the Phœnicians had founded Cadiz, their Gadir in the eleventh century B.C., more than two centuries before the date which, from astronomical considerations, I assign for the building of Stonehenge. We know that they sailed along the shores of Spain and Gaul and to the Baltic, and though they preferred coasting as a rule, the straight cut across from Cherbourg to Poole or Christchurch in fine weather would not be a long voyage; and as they certainly did trade with Britain, and it must have been hazardous for British coracles to sail across the open sea, laden with tin, we may conclude that Phœnician ships did cross the Channel. We know also that the Phœnicians made, more or less, homes for themselves wherever they landed; and it is probable that they did so at Poole or Christchurch, also that they would build them a temple where they found it convenient to stay."

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

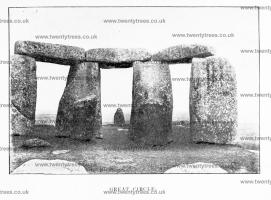

Photos.

Mr. Story Maskelyne considers the Greeks reformed the Temple later on. "Within 500 years of the latest of the above-mentioned dates the Phœnician or Tyrian Empire had ceased to exist, and her numerous colonies had been absorbed by the nationalities surrounding them. About B.C. 400 the Greeks supplanted the Phœnicians in their trade with Britain, and probably for some time continued to use the same mart and sea route the latter had used—we may assume from Cherbourg to Poole or Christchurch, whence they bore away the tin in their coracles from Cornwall. Now commenced a new era for Stonehenge. It must have been a noted Temple, and I cannot doubt that Hecatæus did allude to it as cited by Strabo, when he p. 26wrote, in the sixth century B.C., of the Round Temple to Apollo in the land of the Hyperboreans. Now the festivals of the Greeks were more connected with the months than with the year, and their calendar months were alternate, full and hollow, where the thirty pillars were doubtless used by them for the daily sacrifice in the months of thirty days and the spaces between them, omitting the entrance, for the hollow months, of twenty-nine days. Owing to the precession of the stars, Stonehenge no longer answered some of the purposes for which it has been founded. The Greeks had adopted with ardour the Metonic Cycle discovered by them B.C. 430, and they reformed the old Sun Temple by the addition of the inner horseshoe of blue stones which represented that Cycle, for they were in number nineteen. As to how, or why, the blue stones came to be imported, I imagine they are native to Brittany or Normandy, whence they might easily have been brought as ballast in Greek ships, which took back tin in their stead from Poole or Christchurch, and from the latter port they might easily have been taken in rafts to Amesbury."

All About History Books

The Deeds of King Henry V, or in Latin Henrici Quinti, Angliæ Regis, Gesta, is a first-hand account of the Agincourt Campaign, and subsequent events to his death in 1422. The author of the first part was a Chaplain in King Henry's retinue who was present from King Henry's departure at Southampton in 1415, at the siege of Harfleur, the battle of Agincourt, and the celebrations on King Henry's return to London. The second part, by another writer, relates the events that took place including the negotiations at Troye, Henry's marriage and his death in 1422.

Available at Amazon as eBook or Paperback.

The Date of Stonehenge.

In printing this second edition of my little guide-book, I think it will be found interesting and necessary to leave all the former evidence and opinions that I collected as to the date of Stonehenge. Since the excavations in 1901, I think we may consider the age of Stonehenge to be between three and four thousand years. Mr. W. Gowland judges from the implements or tools found. Sir Norman Lockyer and Dr. Penrose from astronomical observations, based on the fact that the avenue (''Via Sacra") to Stonehenge from the east of the ancients was in a line with the Altar Stone, so that the sun, rising on the day of the Solar half-year (June 21st) and creeping over the horizon, shed his beams on the Altar Stone, thus marking the solar half-year. Of course, the east of the ancients is not our east, but the difference between the position of the sun noio and then to the avenue gives, according to these gentlemen's calculations, a date of 3700 years old to Stonehenge.

The Finds at Stonehenge.

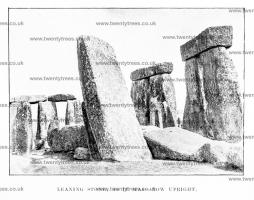

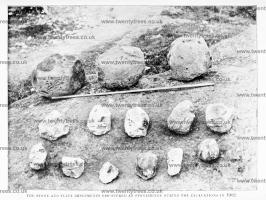

The implements found during the excavations made for the underpinning of the "Leaning Stone" are thus classified by Mr. W. Gowland:—

(1) Haches roughly chipped, longer and shorter. (2) Axe-hammers. (3) Hammer-stones with blunt edge. The above are of flint. (4) Regular hammer-stones of compact sarsen. (5) Mauls of the same rock, weighing from 37 to 64 lbs. each. There were also found chippings from the monoliths, and, near the surface, coins and animal bones.

Only one trace of copper or bronze occurred other than coins and superficial finds, a mere strain on a block of sarsen. So we may consider Stonehenge to belong to the late Neolithic, or early Bronze Period. These objects have been lent by Sir Edmund Antrobus to the museum at Devizes for a period of six months.

In the January, 1902, number of Man, Mr. W. Gowland's interesting paper will be found, describing the excavations, methods of trimming and erecting the stones practised by the ancients.

As to the kinds of stone actually employed in the building of Stonehenge, the whole of the outer circle and the four stones lying beyond that circle are undoubtedly "Sarsen" (which are the boulder stones left by the ice-sheet of the glacial period on the Wiltshire downs). There are, in the inner circle, four stones which have been called "horn-stone." The remainder are "diabase," commonly called "bluestones," and similar are found in Wales, and in parts of Cumberland and Cornwall, the so-called Altar Stone being a kind of grey sandstone, not sarsen. The large outlying stone, known traditionally as the "Friar's Heel [Map]," from a legend that when the devil was busy erecting Stonehenge he made the observation that no one would ever know how it was done. This was overheard by a friar p. 28lurking near by, and he incautiously replied in the Wiltshire dialect, "That's more than thee can tell," and fled for his life; the devil, catching up an odd stone, flung it after the friar, and hit him on the heel. This stone is also named the "Pointer," because from the middle of the Altar Stone the sun is seen at the summer solstice (21st of June) to rise immediately above it. The Hele Stone is the true name, "Hele" meaning "to hide," from Heol or Haul of Geol or Jul, all names for the sun, which this stone seems to hide. From the Friar's Heel it is about 66 yards to a low circular earthen boundary, enclosing the area within which Stonehenge stands. Just within the entrance to this earthen ring lies a large prostrate stone called the "Slaughter Stone," supposed by some to have been used for the slaughter of victims about to be offered in sacrifice at the altar. The Slaughter Stone (at the end nearest to the Friar's Heel) bears evidence of tool-marks, there being six small round cavities made in it by blows from a flint tool. On the margin of the earthen ring, one 55 yards on the left, the other 95 yards on the right of the entrance, are two small, unhewn stones.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

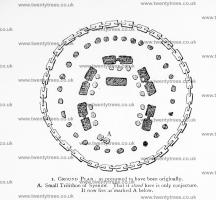

Stonehenge stands about 440 feet above the sea-level. The outer circle measures 308 feet in circumference, and is supposed to have been formed originally of thirty upright stones, seventeen of which are still standing, and the remains of nine others are to be found fallen to the ground. These stones formerly stood 14 feet above the surface of the ground, but now are of different heights. Their breadth and thickness also vary: the former averaging 7 feet, the latter 3½. The stones were fixed in the ground at intervals of 3½ feet, connected at the top by a continuous line of thirty imposts forming a corona or ring of stone at a height of 16 feet above the ground, and were all squared and rough hewn, and cleverly joined together. The uprights were cut with knobs or tenons, which fitted into mortice holes hewn in the undersides of the horizontal stones. About 9 feet within this peristyle was the "inner circle," composed of diabase obelisks; within this, again, was the "great ellipse," formed of five, or, as some think, seven trilithons of stones, each group consisting of two blocks placed upright and one crosswise. These structures rose progressively in p. 29height from N.E. to S.W., and the loftiest and largest attained an elevation of 25 feet. Lastly, within the trilithons was the "inner ellipse," consisting of nineteen obelisks of diabase. Within the inner ellipse we find the Altar Stone. At the present moment, there remains of the outer circle or peristyle sixteen uprights and six imposts; of the inner circle, seven only stand upright of the great ellipse—there are still two perfect trilithons and two single uprights. The Duke of Buckingham, in his researches in 1620, is said to have caused the fall of a trilithon. He was at Wilton in the reign of James I., and he "did cause the middle of Stonehenge to be digged, and under this digging was the cause of the falling down or recumbency of the great stone there, twenty-one foote long." "In the process of digging they found a great many horns of stags and oxen, charcoal batter-dishes (?), heads of arrows, some pieces of armour eaten out with rust, bones rotten, but whether of stagge's or men they could not tell."

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

In 1797, on a rapid thaw succeeding a severe frost, another trilithon fell; of the inner ellipse, there are six blocks in their places; and in the centre remains the so-called Altar Stone.

In Sir R. C. Hoare's "History of Wiltshire," he mentions that Inigo Jones observed a stone, which is now gone, in the inmost part of the cell, appearing not much above the surface of the earth and lying towards the east, four feet broad and sixteen long, which was his supposed Altar Stone. Also "Philip, Earl of Pembroke (Lord Chamberlayne to King Charles I.), did say ‘that an altar stone was found in the middle of the area here, and that it was carried away to St. James's.'"

The entrance to Stonehenge faced the N.E., and the road to it, "Viâ Sacra," or avenue, can be traced by banks of earth.

It is the opinion of competent authorities that many of the stones should be underpinned in the manner of the "Leaning Stone," as any violent storms, such as periodically sweep across the Plain, might bring them down. The fall of two of the stones from the outer circle (supposed by the superstitious to foretell the Queen's death) on December 31st, 1900, the last day of the old century, and 103 years p. 30after the last stones fell, was caused by a gale from the west.

There are the two opinions as to the right course to pursue regarding Stonehenge—some people considering it would be well to leave it to fall down, so that eventually it would appear like a jumbled heap of ninepins, others (myself among the number) that the necessary steps for its Preservation, not Restoration, should be taken.

Florence C. M. Antrobus.