Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Antiquaries Journal V1 1921 Page 183 is in Antiquaries Journal V1 1921.

Wayland's Smithy [Map], Berkshire. By C. R. Peers, Secretary, and Reginald A. Smith, F.S.A. [Read 16th December 1920]

I. The History of the Monument

In Northern mythology Wayland the Smith corresponds to the Roman Vulcan or the Greek Hephaestus; and his name cannot have been attached to the well-known group of sarsen slabs in Berkshire till the Teutonic invaders reached the upper Thames in the fifth century. This cunning worker in metals appears on the Franks casket in the British Museum, dating from soon after 700; and the monument is mentioned under the name of Wayland's Smithy in a charter of King Eadred to Aelfheh dated 955.

The site is two miles from the western boundary of the county, one mile east of the village of Ashbury, and the same distance south-west of the White Horse near Uffington. It is now encircled by beech-trees near the brink of the downs, about 700 ft. above the sea; and 220 ft. to the south runs the prehistoric track known as the Ridgeway. The legend connected with the stones is well known and has been discussed by Thomas Wright in Archaeologia, xxxii (1847), 315, and Journ. Brit. Arch. Assoc., xvi, 503 also by Dr. Thurnam in Wilts. Arch. Mag., vii, 321.

Mention may also be made of Oehlenschlager's treatment in Wayland Smith, from the French of G. B. Depping and F. Michel, with additions by S. W. Singer, published in 1847; but the tradition has been kept alive above all by Sir Walter Scott, who gave a garbled version of it in Kenilworth. That the novelist never visited the monument but derived his information in London from Madam Hughes, the wife of the Uffington vicar. (who was also canon of St. Paul's) and grandmother of Tom Hughes (the author of Tom Brown's Schooldays), has been established by the researches of Mr. H. G. W. d'Almaine, town clerk of Abingdon, to whose zeal and pertinacity the recent exploration of the site was chiefly due. The Smithy has for years been scheduled as an ancient monument, and the Earl of Craven, as owner, not only readily gave permission but generously provided the labour for the excavations, which were carried out under our own supervision in July 1919 and June 1920. Subscriptions towards incidental expenses were thankfully received from the Berkshire Archaeological Society and its honorary secretary, Rev. P. H. Ditchfield, F.S.A.; also from Rev. E. H. Goddard, honorary secretary of the Wiltshire Archaeological Society, and from our own Society. Mr. d'Almaine not only took an active part in the arrangements, but made two models; and Rev. Charles Overy of Radley College burdened himself with apparatus, and undertook with success most of the measuring and photography. Subsequently, the human bones discovered were skilfully repaired and fully described by Mr. Dudley Buxton, of the Oxford Anatomical Museum. Lord Craven's agent, Mr. Beresford Heaton, did us great service, and his local representative, Mr. McIver, loyally carried out his instructions to the advantage of the party and the venerable site itself. To all these gentlemen we hasten to convey our thanks, and regret that three beech trees within the enclosure had to be felled, as their roots were interfering with the stones of the chamber.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

The earliest illustration known or likely to be found is a rough sketch by John Aubrey about 1670 (fig. i), reproduced in Wilts. Arch. Mag., vii (1862), 323 from his Monumenta Britannica in the Bodleian library. The chamber and surrounding stones are evidently not on the same scale, but the outline and measurements of the barrow (about 203 ft. by 66 ft.) are approximately correct. The standing stones on the south-east border of the mound are still in position, but most of the others shown as above ground have disappeared; and our excavations have brought to light several that had fallen and been covered up before his time. It may be possible eventually to disclose the stones now lying concealed in his gaps. The chamber is very summarily drawn, Aubrey perhaps starting the notion that the eastern transept was a cave; and it is curious that most of the illustrations and accounts of the monument published since his time have perpetuated the error, as for instance Chambers's Book of Days, July 18, vol. ii, 83 (published in 1888).

The next publication is dated 1738, and took the form of a letter to Dr. Mead concerning some antiquities in Berkshire, by Francis Wise. His plate opposite p. 20 shows the entire barrow with rather angular outline, highest at the south end and irregularly covered with stones, among which the chamber can be barely identified. There is also a nearer view, taken from the west, and showing the earlier approach from that side, whereas the path from the Ridgeway now leads to the south end of the monument. The stones are woefully out of drawing, but roughly represent the present arrangement at the southern end of the barrow.

His distant view is reproduced in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, vol. xxi (1833), p. 88, this and another reference to vol. viii (1826), p. 33 having been furnished by Dr. Eric Gardner, F.S.A. The later view represents the 'Cave' surrounded by fir-trees, with water in the foreground (perhaps in the fosse), and a separate stone on either hand (on the west of the chamber). In the interval of nearly ninety years a belt of fir-trees had grown up round the barrow; and Thurnam states that firs and beeches were planted about 1810, the former being dead in 1860. No trees are included in Lysons's plate published in 1806 (description in Magna Britannia, i, 215 of the 1813 edition).

Sir Richard Colt Hoare wrote of the monument in 1821 (Ancient Wilts., ii, 47): — "It was one of those long barrows, which we meet with occasionally, having a kistvaen of stones within it, to protect the place of interment. Four large stones of a superior size and height to the rest, were placed before the entrance to the adit, two on each side; these now lie prostrate on the ground: one of these measures ten and another eleven feet in height; they are rude and unhewn, like those at Abury. A line of stones, though of much smaller proportions, encircled the head of the barrow, of which I noticed four standing in their original position; the corresponding four on the opposite side have been displaced. The stones which formed the adit or avenue still remain, as well as the large incumbent stone which covered the kistvaen, and which measures ten feet by nine.' He notices the north and south axis of the barrow as exceptional, but somewhat perversely states that * the kistvaen is placed towards the east ', not realizing that the whole of the chamb/sr was originally roofed with capstones like that of the eastern transept. It was, however, recognized a hundred years ago that the sarsens once formed the chamber of a long barrow and that the entrance was flanked by two pairs of enormous stones now fallen.

The first careful drawings of the Smithy were published in Archaeologia, xxxii (1847), 312, pl. xvii. They were the work of C. W. Edmonds and illustrated a paper on the monument by a former secretary of the Society, John Yonge Akerman. The chief merit of this paper is its recognition of the cruciform plan, but in this he was anticipated by Stukeley who died in 1765 (Surtees Society's vol. Ixxvi, 8).

A pointed contrast in method may be seen in Wilts. Arch. Mag., vii (1861), which contains an account and drawing of the monument, both bristling with inaccuracies (p. 315), followed by a sober account from the pen of Dr. Thurnam (p. 321). The latter gives as much information as was possible without systematic excavation, and is fully worthy of one of the greatest names in British archaeology. References to the literature of the subject are given in his note on p. 330 [Wilts. Arch. Mag. p. 330].

At the International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology at Norwich and London in 1868, the late Mr. A. L. Lewis read a paper "on certain Druidic monuments in Berkshire" (Report, pp. 38, 44). He accepted the cruciform plan of the Smithy and thought the gallery had been cut into two chambers by two of the wall stones being set crosswise. In his opinion the monument was intended for use as a tomb, not as an altar, and the mound that probably covered the supporting stones (leaving the capstones exposed) would not have contained much material. His plate gives, a plan of the stones surrounded by trees, and he refers to the abundance of sarsen stones at Ashdown, two miles to the south, which are said to have been still more numerous before the house was built (Ashmole, Antiquities of Berks., ii, 198).

The chambered long barrows of England may be said to agree in type, but each has its peculiarities, and Wayland's Smithy has more than usual. Thurnam states in his paper on Long Barrows (Archaeologia, xlii, 205) that two out of three, perhaps four out of five, have their long axes approximately east and west: the rest are about north and south, and both Nympsfield [Map] near Dursley, Gloucestershire and Nempnet [Map] in Somerset, nine miles SSW. of Bristol, like Wayland, have their chamber at the south end. His plate xiv is useful as showing side by side the plans of several such chambers, but no true parallel for the simple cruciform arrangement of the stones is there given. Borlase (Dolmens of Ireland, ii, 457-8) saw a resemblance to the long barrow at West Kennet, Wilts., which had squarish ends (Archaeologiay xxxviii, 409) and a stone enclosure, according to Aubrey's drawing of 1665. The dimensions in this case were 336 ft. by 75 ft., the narrow end being 40 ft. across.

In the Archaeological Review y ii (1889), 314, Sir Arthur Evans compared Wayland's Smithy with one of the monuments at Moytura, co. Sligo, of which a view and plan are given in Fergusson's Rude Stone Monuments, pp. 182, 183. The lower limb of the cross is imperfect, but there were evidently two rings round the chamber, the inner being of small stones; and the opening in the outer, opposite the base of the cross, is flanked by two stones that may be door jambs or the rudiments of an avenue, or (as Fergusson preferred) an external interment. The diameter of the outer circle is 60 ft.; the monument is no. 27 in Petrie's list.

A good foreign example of a chamber with massive jambs at the entrance was excavated by Gustafson in 1887 in Bohuslen and illustrated in his Norges Oldtid, p. 33, fig. 113 and p. 38, figs. 132, 133. English examples are not so definite, but Thurnam speaks of "the two large stones which in the best marked examples of these chambers form the door-jambs to the entrance ', and gives some references in Archaeologia, xlii, 222, note b [1].

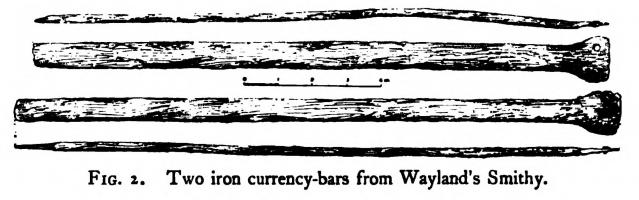

The four prostrate slabs at the south end of the barrow proved, when completely laid bare, of imposing dimensions; and an east and west trench was dug to discover their original purpose. Not only were the sockets made for them in the chalk discovered with small lumps of sarsen to act as wedges at their feet, but on the northern edge of the trench, opposite the foot of the slab immediately west of the entrance, two flat rods of iron were taken out together (fig. 2). They were lying parallel to the foot of the jamb, I ft. from the present surface, and looked like door-hinges, but the only perforations are in the expanded end of each, and another interpretation was needed. Though a novel variety of the type, they are evidently currency-bars of Early British origin, such as Julius Caesar described (Bell. Gall. v. 1 2), and no doubt saw during his invasions in b.c. 55-54. Apart from the expanded end the section is oblong and quite normal, the longer weighing when found 11¾ oz. and the shorter just over 12½ oz. After deaning and treatment to prevent further rust by Dr, Alexander Scott, F.R.S., at the British Museum, the weights are respectively 11 oz. 30 grains and 12 oz. 20 grains. The standard based on independent evidence is 11 oz. (4,770 grains = 309 grammes). Several papers have been published on the subject (Proc. Soc. Ant.y xx, 179, xxii, 338, xxvii, 69; Archaeological Journal, Ixix, 424; and Classical RevieWy 1905, 206).

The discovery of currency on such a site inevitably leads to speculation. According to the legend, a traveller whose horse had cast a shoe on the adjacent Ridgeway had only to leave a groat on the capstone, and return to find his horse shod and the money no longer there. But the invisible smith may have been in possession centuries before the Saxons recognized him as Wayland, and the ancient Britons of Caesar's time may have been in the habit of offering money here either in return for farrier's work or merely as a votive offering to the local god or hero. In Sicily a similar tradition can perhaps be traced back to the classical period (Archaeologia, xxxii, 324).

Whatever the motive, we have to explain how the currency bars came to be buried at that particular spot, which was on the inner side of the enormous jamb and not accessible, even from the passage, when the mound was in existence. As matters now are, there is no reason why treasure should have been buried there rather than inside the chamber; but a votive offering deposited at the base of the largest standing stone would have been most appropriate, and the suggestion is that one of the jambs at least was standing about 2,000 years ago. On that theory we must also presume that the surface was then much as it is now, else the position would have been unapproachable without a deep excavation. In other words, the find of currencybars not only points to a British predecessor of Wayland, but indicates that although this particular jamb was still standing, the long barrow had been already denuded to its present level in the first century before Christ.

Except for two capstones to cover part of the lower limb of the cross, all the stones of the chamber are accounted for. Though there is nothing to show when the capstones were displaced, it is probable that much of the damage was done on one occa§iop, possibly without the intervention of man. The capstone of the crossing was on a higher level than the rest, and probably was the only one visible on the original surface of the barrow. This huge slab has fallen and sunk into the ground on the north-east of the chamber. In its fall it also disturbed its neighbours, forcing the capstone of the northern arm between the eastern upright of that chamber and the northern upright of the eastern transept. In sliding down to the north-east it also tilted towards the south the northern upright of the northern limb of the cross, and depressed the north-west angle of the vast capstone that still covers the eastern transept. The weight of the central capstone is estimated at 1½ tons, that still in position being about 3½ tons. The capstone of the western transept has slipped off to the north, where it now lies, and the last capstone to the south has fallen and partly closed up the entrance to the chamber, its dimensions being 3 ft. 9 in. by 3 ft. 8 in.

It should be noted also that the capstone of the northern arm of the cross originally rested on top of the north and east uprights, but on a ledge cut on the inner face of the western upright, 9 in. from the top, on a level with the top of the others. The northern capstone was thus accommodated under the projecting edge of the large central capstone, to which it gave additional support. On the inner face of the south-east pier of what may be called the central tower were observed four circular depressions that might rank as * cup-markings ', but in any case they are not good examples, nor can their date be determined in relation to the chamber.

Wayland's Smithy may thus be said to have a history, certainly more than the later and more celebrated Stonehenge; and recent excavations have added largely to our knowledge of both monuments. Wayland, however, still retains some of his secrets; and if and when the omens are favourable, more may be done to lift the veil. For the present all concerned have done their best to answer King Alfred's question in his free translation of the Consolations of Boethius:

Ubi nunc fidelis ossa Fabricii manent? quid Brutus, aut rigidus Cato?

'Where are now the bones of the celebrated and wise goldsmith Weland? Where are now the bones of Weland, or who knows now where they were?'

In the report on the human remains by Mr. Dudley Buxton, detailed measurements are recorded that need not be published in fulU As will be seen later, nearly all the interior of the chamber had been previously dug over, but the lower levels of the western transept still contained some human bones in groups, though not in anatomical order. Here, as elsewhere, skeletons had been disturbed to make room for other burials, and it is probable that the dead were first buried outside and after a time disinterred, for the bones to be laid in the tomb reserved no doubt for the greatest of their time.

Here we found remains of perhaps eight skeletons, including one of a child, but their incompleteness points to a previous disturbance perhaps in neolithic times. The absence of thighbones in this case is remarkable, and only a few conclusions can be drawn. The best preserved skull belonged to an adult of middle age, probably male, with a cephalic index of 78.19, the mean indices of long and round barrow subjects being 74.93 and 76.70 respectively. It is therefore broader in proportion than the average brachycephalic Bronze Age skull, and may belong to an intrusive burial after the introduction of metal. In Mr. Buxton's opinion the people buried in Wayland's Smithy did not differ to any great extent in physique from the more recent inhabitants of Berkshire. Certain differences from modern bones, due to habit, are striking, namely the pressure facets which may be all attributed to squatting, and the wear of the teeth, both of which are characteristics shared by primitive man and by modern savages.

Near the middle of the western skirt of the barrow, 3 ft. outside the line of standing stones and on the line of our trench BB, was found a skeleton buried in a crouched position, and lying on its right side, with the head to the north. It was only 1 8 in. below the surface, and had been partly destroyed, probably in digging for rabbits. It is pronounced to be that of a man of about 5 ft. 2½ in., below the average height therefore, but with a cranium larger than usual. The muscular development is slight, and the teeth are less worn than those found in the chamber, with no trace of caries. The cephalic index is 77.72, indicating a slightly longer type of head than before, though both belong to a type living in England both in neolithic and modern times. In spite of a careful search, no grave furniture was found to give a clue to the date.

EXCAVATIONS

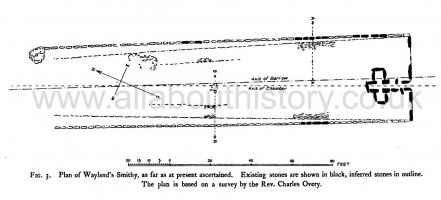

Much has been revealed by the few days' excavations which were made in 191 9 and 1920, but the whole story is not yet told. The present account must be taken as an instalment, which we hope soon to supplement, and may well have to correct. The first season's work was directed primarily to a careful clearing of the passage and burial chambers, but it was also found possible to make progress with the verification of the plan of the barrow and to demonstrate that the theory of a circular setting of facing blocks was untenable. The second season brought the plan to its present state and threw considerable light on the construction of the barrow, leaving for further research the possible discovery of more facing slabs and any evidence which may remain of the north end of the barrow. For the present the estimate of 185 feet for the full length from north to south may stand.

The site is little if at all raised above its immediate surroundings, and the barrow was probably set out on level ground. The wider end, containing the burial chambers, is at the south, towards the Ridgeway. It is 43 ft. wide, and in it were set four large standing stones, which now lie prostrate in front of it. Two of these stones were at the east and west angles respectively, the other two irregularly spaced between them, and the entrance to the grave chamber was between these two stones, though not, as it seems, on the long axis of the barrow, and therefore not in the middle of the south end. The stones, like all others in the barrow, are sarsens, and though not to be compared with the great stones of Avebury or Stonehenge, are yet of sufficient size to have formed an imposing front. The largest is 11 ft. long and 8 ft. wide, and must have stood between 8 ft. and 9 ft. high when in position, and all four must have projected above the contour of the barrow if, as there is reason to suppose, the highest capstone of the burial chamber was level with the top of the mound. The construction of the barrow can best be described under three heads: the mound, the revetment, and the facing.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Abbot Ralph of Coggeshall describes the reigns of Kings Henry II, Richard I, John and Henry III, providing a wealth of information about their lives and the events of the time. Ralph's work is detailed, comprehensive and objective. We have augmented Ralph's text with extracts from other contemporary chroniclers to enrich the reader's experience. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

The mound is chiefly composed of the chalky surface soil, but in the southern or head end of the barrow there is a considerable proportion of loose sarsen rubble, and this may have formed the principal material for the first 60 ft. from the south, the chalky soil being only used as a substitute when the supply of stone failed. The northern parts show only a few isolated groups of stones, and though this end has been more thoroughly robbed than the rest, it does not appear that they are the remains of a stone filling. One group, set on the original surface on the axis of the barrow, looks rather like part of the original setting out, and this is very nearly midway in the length of the barrow.

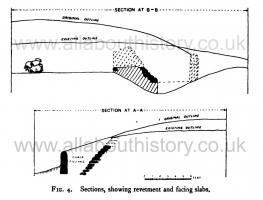

The revetment is formed of sarsen rubble, laid flat in irregular courses. A section midway in the barrow (fig. 4) shows it to consist of an inner and an outer face, the former about 2 ft. thick and the latter somewhat less, enclosing a core of hard chalk and soil, the whole being about 6 ft. thick at the bottom with a batter of about 45° on the outer face: just enough is left of the inner face to show at what angle it rose. Farther to the south, where there is much more stone in the core, the section is less clear, as regards an inner face, though it probably existed. The greatest height of the revetment cannot have exceeded 6 ft. at any time, and there are no evidences that it was ever carried right over the top of the mound.

The facing was composed of slabs of stone of an average thickness of 14 in. to 16 in., set upright along both sides and presumably the north end of the barrow. It will be seen that they were not set parallel to the revetment but, starting against its east and west faces at the south end, diverge from it northward. Eleven stones remain on the east side, of which all but four have been disclosed by our excavations. One is undisturbed in its original position; four more are more or less upright, the rest have ^en outwards. On the west side only four stones, all fallen, have been discovered so far. It is notable that the filling between these stones and the revetment is of pure chalk unmixed with earth, in contrast to the material of the mound. The average height of the facing stones above ground-level was about 3 ft.

Is the barrow one work or of several dates? The divergence of the facing stones from the revetment suggests the possible addition of the former, but the most material argument is found in the section (B-B). It appears that a ditch ran along the west side of the barrow, the revetment being on its inner slope, and at a level which suggests the partial filling in of the ditch when the revetment was built. The facing slabs would have made a further filling in necessary. The ditch was doubtless caused by the making of the mound, and it may be argued that the revetment is an afterthought, for if it had been intended from the first, room would have been left for it within the line of the ditch. On the east side of the barrow no ditch has so far been found, but excavations have not been carried down to the undisturbed soil. The divergent lines of the revetment and facing slabs have already been noted. At the south end of the barrow the revetment, if its general direction continued, would come practically to the east and west angles, and the facing slabs would be set immediately against it. Constructionally, a space between the two is of value, as the slabs are ill-adapted to resist lateral pressure, and the revetment was intended to do the whole work of containing the mound. The chalk filling between the revetment and the slabs serves merely to carry on the contour of the mound. Here, again, it may be argued that if the feeing slabs had been part of the original design, a space for them would have been provided in setting out the south end of the barrow, and they would have run parallel to the revetment.

The burial chamber consists of a passage 21 ft. long by 2 ft. 1 in. wide, open at the south end. Near the inner or north end lateral chambers open from it west and east, making a cruciform plan. The floor, where undisturbed, seems to be at the original level of the ground. The largest stones are the four which flank the openings to the east and west chambers, and the passage at this point would have been 6 ft. high to the under side of the capstone. The rest of the passage averages 4 ft. 6 in. in height, while the eastern chamber, the only part in which the capstone is still in position, was less than 4 ft. high. Seeing that this chamber is the origin of the cave legend, and the sole inspirer of Sir Walter Scott's romance, the value of imagination in archaeological matters is here aptly illustrated.

When it is remembered how much the body of the barrow has suffered, it is a most fortunate thing that so many of the stones of the grave are preserved. Of the uprights only one is missing and one displaced, while of the seven — or possibly eight— coverstones five are in existence, and one of them still in position. The stone which covered the north end of the passage is wedged in between the north-east upright of the 'crossing' and the capstone of the east chamber, which is still in position, though somewhat shifted in a north-easterly direction.

The capstones of the crossing and of the western chamber lie on the ground north of the grave, while the southernmost coverstone of the passage is now half buried in the ground in front of the original entrance.

The construction of the grave is on the usual lines. The upright stones are set in holes in the original ground surface, which, as far as we ascertained the depth, are comparatively shallow, but the strength to sustain the pressure of the mound against their sides was probably adequate when the monument was complete. The spaces between the stones were evidently filled with small dry-set rubble as usual. The northern stones of the two chambers and of the passage now lean inwards, but this has probably occurred since the grave has been exposed. The construction of the southern part of the passage is interesting, there being on each side a stone set at an acute angle with the direction of the passage, and on the west side, at any rate, so much taller than the stones next it that it could not have served to carry a coverstone. I think that their object was to stiffen the side of the passage against lateral pressure, to which they obviously offer a greater resistance than the stones set with their long sides in the direction of the passage.

The one upright stone which is missing is the third from the south on the east side of the passage, and from the displacement of the soil here, and of the diagonal stone next to it on the south, and also from the loss of the cover-stones on this part of the passage, it seems that at some time an entrance has been forced into the grave at this point. There is nothing now to show how the passage was closed at the south end, but the outward curves of the two end stones are to be noted. The development of this feature is to be seen in the curves of dry-built walling flanking the entrances to the burial chambers at Stony Littleton, Uley, St. Nicholas, and elsewhere. It must be presumed that the south end of the barrow was built up in dry rubble between the standing stones, and there may have been, as at Uley, a deep lintel-stone over the mouth of the passage.

In a few instances, particularly on the inner faces of the east chamber, the stones have been carefully worked to a true face, with results which are precisely those obtained at Stonehenge.

We can hardly expect to bring the study of prehistoric tooling to anything like an exact science, as, within limits, we can do with medieval tooling; but instances of this sort multiply, and it would be interesting to compare the dressing with the tooling at Maeshowe in the Orkneys and elsewhere. We may suppose that flints or hard stone would be the means by which such marks were produced.

The barrow when complete must have appeared as a very low and flat mound limited by the line of facing slabs. But the discovery of the contracted burial outside this line shows that the soil of the mound had extended beyond the slabs at an early date.

The rectangular plan of the barrow has a parallel in that of the chambered mound at St. Nicholas, near Cardiff, which was fully explored by Mr. John Ward, F.S.A., and described by him in Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1915, 6th Ser., vol. xv, pp. 253-320. The barrow, being in a district where stone is plentiful, is composed of stone slabs of various sizes throughout, and has a dry-stone revetment built in level courses to contain the substance of the mound, with a vertical outer face, the upright slabs which are so noticeable a feature at Wayland's Smithy being absent. The construction is less calculated to sustain a thrust than the battering revetment described above, and Mr. Ward found that it had been pushed outward in many places. In the St. Nicholas barrow occur lines of stones set upright in the body of the mound, evidently to serve as stifFeners to the mass of rubble, and though nothing of exactly this character occurs in Wayland's Smithy, certain isolated heaps of stone may be the remains of some setting out of the same nature. Stone, except in the form of sarsens, is absent from the district, and earth and chalk formed a far larger proportion of the Berkshire barrow than the soil and clay found in its Glamorganshire parallel.

Another barrow which seems to have been rectangular is that of Coldrum, Kent, described in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute for 1913, p. 76. There appear to have been facing slabs along the sides of the mound, which is now in a very ruinous condition. The proportions are very different from the normal; it appears that with a width of some 50 ft. the length was about Soft. Only the inner end of the grave chamber remains, and the entrance, which was at the east, is quite destroyed.

DISCUSSION

Mr. d'Almaine said he had been studying the monument for seven years, and had collected material to elucidate its problems. The machinery had to be devised and set going, the result being that the Smithy had been not only explored but reported on; and he hoped it would be permanently protected. His first motive was to prevent the sarsens being split by picnic-fires, a danger that had not been met by scheduling it in 1882 or putting it under the Act of 1913. The Inspector had given him encouragement, and he desired to express his obligations to the Earl of Craven and his agent, Mr. Beresford Heaton. Mr. Overy's plans and photographs of the excavations had been invaluable, and he looked forward confidently to the day when the enclosure would be handed over to the nation.

The President said the joint paper was one of special interest and contained enough romance to stir the imagination of all present. The legend was familiar enough, but it was surprising to find that money-offerings at the monument might go back to Caesar's time; and the survival of the legend was all the more extraordinary, as there was evidently classical authority for it in the Mediterranean area. It was illustrated about A.D. 700 on the Franks casket in the British Museum. With regard to the treatment of human bones after burial, he might refer to the inclusion of more than one skeleton in the large Bronze Age jars of southern Spain discovered by the brothers Siret. Recent research had seriously damaged Scott's reputation as an archaeologist, but had not fixed the date of disturbance by treasurehunters. The use of the iron bars as currency was highly probable and their identification was due, in the first place, to Mr. Reginald Smith. The cruciform plan was yet another argument against regarding everything in the shape of a cross as of Christian origin. Thanks were due not only to the authors but to Mr. d'Almaine for his initiative and excellent models; to Mr. Overy for his measurements and photographs; to Mr. Buxton for examining the bones; and to the subscribers for their enterprise in the cause of archaeology.