Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Archaeologia Cambrensis 1844 Pages 129-144 is in Archaeologia Cambrensis 1844.

It is singular that a subject generally, or rather almost universally, supposed to have been settled long ago, should have been seriously proposed as an important subject of discussion at the Fishguard Meeting in 1883. But singular as it is, it is a hard fact that such a subject was proposed; and although the question speedily collapsed, yet those who had imperfect and erroneous ideas of cromlechs in general must have thought it odd that such a question should be started and disposed of so summarily. These observations will be better understood by the announcement in the annual official Report, which runs thus: " They venture confidently to anticipate their meeting here (Fishguard) will be the means of eliciting further information concerning those megalithic remains which are so peculiarly abundant in this district; and it is hoped the research and deliberations of the Association may in some measure determine what are the true origin and purpose of these ancient monuments."

At the meeting of the Committee held immediately before the public meeting, Mr. Barnwell objected to the above clause, on the ground that the question had been settled many years ago,—at least among the antiquaries of this and other countries of Europe,—and moved that it should be struck out. It might have been supposed some one present would have seconded the proposal; but no one did so, and the proposal dropped to the ground. It is easy to understand that many present believed in the statements of Fenton, — a gentleman so intimately connected with Fishguard by connexions and residence; for though born at St. David's, he made this place his usual residence, ouch would puzzle themselves about the use or object of the proposed inquiry, as if those who set it on foot expected to make some important discovery. They must have been disappointed when they heard that the author of the part objected to was, after all, of the same opinion as the objector. The most remarkable incident was the general silence of the other members and officers of the Society, who thus approved of the clause by letting Mr. Barnwell's proposal fall to the ground, and informing all readers of the Journal that the Society could sanction the statement that the object and history of our cromlechs was still a question to be solved. The fact is, it was a case of par- turiunt mo7ites, except that the mouse brought forth was very ridiculus, and the Society itself made not less so.

After the numerous articles which have appeared at various times in the Archceologia Cambrensis, which have clearly set forth the real nature of the class of ancient stone monuments called "cromlechs", it would appear very unnecessary to repeat them here; but after the revelation at the Fishguard Meeting it may be useful to restate what has been already stated elsewhere. It is thought that to the majority of members such a step might seem totally unnecessary; but when learned and experienced individuals are dumb on such a question, the only inference is that they had no opinion of their own, or were too timid to state it. There is, however, a large number of intelligent people who, as already mentioned, have been satisfied with the scanty and frequently incorrect statements of Fen- ton and others, as their fathers were before them; and to such the following remarks may seem deserving of consideration. This subject may be divided into three sections:

1. Who were the cromlech builders?

2. At what time they were built.

3. For what object were they intended?

The first two sections have not as yet been satisfactorily explained, nor with our present information are they likely to be. As to the third there is not the same difficulty, in spite of what old antiquaries have told us with such confidence that they do not appear to have any doubt on the subject. Thus, from Camden to Fenton they all say nearly the same thing, namely, that they are nothing more nor less than Druidic altars. Thus Stukeley; Rowland, the author of Mona Antiqua, perhaps the oldest of the set; Awbry, the Wiltshire antiquary; Pennant, Hoare, and Fenton. With them also may be mentioned the most popular of former Breton antiquaries, such as Mahe and his opponent, M. Freminville (another Fenton), Delandre, and others, who put all these ancient stones to the credit of the Druids.

Since those days these views have given place to others of a different character, so that those who still talk of Druidical stones are laughed at. It is true that even to the present days we have plenty of Druids and even Arch-Druids, Bards, Ovates, etc.; but all these are inventions of late mediaeval times. These are termed "Neo-Druids", as distinct from the ancient and genuine ones, who have long since utterly vanished, and left no vestige of themselves and their monuments.

From the fact that these stone monuments, especially the cromlech, have been so generally held to be Druidic, some reasons should be given for this belief; but none, not even remote traditions, have been brought forward in favour of such theories.. On the contrary, local traditions ascribe such remains to King Arthur, as the huge work in Gower and in Merioneth not far from Cricceth, where we find more than one instance. A cromlech nearCorsygedol House is named after the same British hero. Other instances might be mentioned; but we are not aware of any case of their being attributed to Druids by local tradition. They are sometimes assigned to the Devil, as the well known monument in Clatford Bottom, near Marlborough, called "The Devil's Kitchen" or " Den", and of which an excellent view is given in the latest contribution to The History of Wiltshire Antiquities, by the Rev. A. C. Smith, the well known. Secretary of the Archaeological Society. The stones in the Vale of the White Horse, in Berkshire, called " Weyland Smith's Forge", have a curious legend connected with them, but not a single trace of Druid myth. Many other cases might be mentioned, all tending to show that in no instance is there any trace whatsoever of Druidism.

On the other hand, if they are, without exception, sepulchres more or less perfect, then the Druidic theory must be given up; and that they are so will probably be acknowledged by those who will be at the pains to examine even the most unlikely specimen.

The first point to be laid down is that those who built them took great care to do the work effectually, and make the resting-places of their friends as secure as possible. This could only be done by the employment of massive stones for the sides and covering-slabs of the chambers. But such chambers required further protection from weather or small animals; and this was effected by heaping up huge mounds of earth, sand, or small stones. In the case of the Pyramids of Egypt more elaborate and more costly methods were adopted for the same purpose. Whether the builders of our cromlechs believed, like the Egyptians, in the transmigration of souls, cannot be asserted, much less proved; but the probability that they did so is very considerable, judging from the great care they took to protect the body from being disturbed, and the grave from being violated.

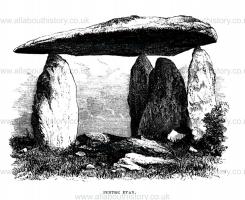

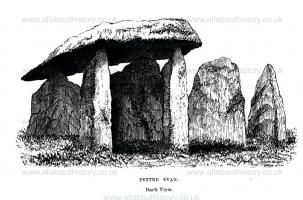

Objections, however, have been made, and perhaps will still continue to be made, that there are some monuments of the kind that never could have been so covered up, either from their form or size, or from the absence of soil or other material. A notable illustration of the supposed difficulty is furnished by the Pentre Evan Cromlech. Its enormous height, and the rocky ground on which it stands, have been more than once brought forward as proofs that it was never even intended to be buried under a mound; and it must be admitted that there is some apparent ground for such an idea. Bat on the other hand it may be said that there is nothing impossible, as there are in existence at the present time structures much larger, still under their covering mound, which were never intended to be concealed.

What could have been the object of those who erected this and similar monuments? They could not have been intended for altars. Mr. Fergusson, the author of Rude Stone Monuments of all Countries, however, tells us that "such an exaggerated form as Pentre Evan seems to be a tour de force; but of still more modern date than the monuments at Plas Newydd, Anglesey, or Arthur's Stone." (P. 174.) By a tour de force he means a monument of huge dimensions, raised not only to commemorate some event, but to hand down to posterity evidence of the skill and strength of those who built it.

If this theory be admitted, it is clear that they were never intended to be covered up, as thus all their labour would be thrown away. But the value of this writer as an authority will be easily understood by the notice on South Wales cromlechs in the Archæologia Cambrensis of 1872, where will be also found a review of his work, and in The Saturday Review of the time.

Another division of cromlechs is that called freestanding, approved by Bonstetten, who divides dolmens into several divisions, the first of which he calls apparent, and Fergusson, free-standing. But if they are a distinct class, as supposed, neither of these writers gives the least hint as to their object. A perfect specimen is in the parish of St. Nicholas in Pembrokeshire, There are also said to be demi-dohnens. But both these kinds are simply the remains of once perfect chambers, and never were intended to be what they are at present. We may, therefore, omit all further notice of them.

Among our more distinguished antiquaries, the late Sir J. Gardner Wilkinson for years would not assent to the statement that all cromlechs or dolmens were buried in mounds; but latterly he was inclined to change his view, from a small chamber in Marros, about seven miles south of Laugharne, in Carmarthenshire, and to announce this change in one of his excellent articles. Another sudden conversion of the same kind was effected in a well known clergyman of Glamorganshire, by a visit paid to the remarkable chamber of Bryn Celli Ddu [Map], in Anglesey. In this case a considerable portion of the covering tumulus remains. It has been described by Pennant and by contributors to the Archæologia Cambrensis. Other covered chambers in Wales, as those at Plasnewydd in Anglesey, and at Dyffryn in Glamorganshire, are well known, and have been figured and described in the Society's Journal. Even in cases where the covering has vanished, in most instances the stones used for this purpose are still scattered around. One of the best examples of this is Arthur's Stone [Map] in Gower, the lower part of which is still partly buried in the débris. Where stones are abundant, and not wanted for local purposes, they are often left undisturbed, and thus give their testimony of their former employment. On the other hand, where earth was used, it was valuable, especially after its exposure to the air for so long a time, and would be soon carried off by the farmers of the neighbourhood. This is apparently the proper explanation of the complete destruction of the covering of these structures. The ground on which the Pentre Evan Cromlech stands at the present time is bare enough, and from its elevated position was not likely to have supplied sufficient earth to cover Up the whole of the group; for there were at least two chambers, the main one and a smaller one. But at any rate an immense quantity of soil was indispensable, and must have been brought up from the lower ground. There is, near Vannes, in the Morbihan, an enormous tumulus known as "Tumiac", as if it was the tumulus, surpassing all others in the district. The ground is bare and rocky. To supply material they brought up from the sea-shore below sufficient sand to form this huge mound, although inferior to our own Silbury. That the Pentre Evan Cromlech [Map] was also once covered up there can be little question.

We are often inclined to judge of such monuments as if they were in their normal and original state. No allowance is made for the effects of exposure to wind and rain for centuries, or for generations of improving farmers or builders of stone roads; all which causes have produced such changes in the original structures as to make it difficult to imagine that the present ruins were once neatly contrived chambers of the dead, carefully planned so as to give an almost perpetual protection to the remains of the dead.

With few exceptions, there is little difficulty in making out the original arrangements, for they are almost universally the same. Thus, for example, it is easy to ascertain the entrance, generally looking east. The exceptions to this position are so few that practically they are of no importance. Another fact is now generally admitted, that these chambers were adapted for subsequent interments, and the larger ones were used for several generations. It was necessary, therefore, to have some guide for the excavators. The position of the entrance was easily obtained if the chambers were uniformly placed in one direction. But there was another difficulty when the exterior of the entrance was laid bare. Unless the large slabs that formed the entrance were unconnected with the covering slab or slabs on which the superincumbent mass lies, it would be impossible to enter the chamber without bringing down and destroying the whole structure. The difficulty was surmounted by taking care that the stones that closed the entrance did not touch the capstone, so that the removal of the entrance-stones was safe and easy. Hence it is that we usually find only these stones wanting.

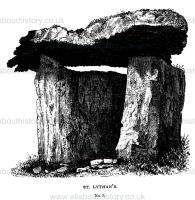

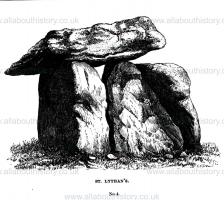

The best illustration of this more simple form is the cromlech1 at St. Lytham [Map] for South Wales, that for North Wales is near Criccieth, and for England, Kit's Cotty House [Map], near Maidstone, which has been so frequently engraved that it is probably known to many. Many other instances may be mentioned; but these three are the most satisfactory examples. The Newport Cromlech,2 visited last year, is another good example, and must be well known in the district. None of the above mentioned cromlechs could, from their form, serve as altars, much less so when buried under a mound. Mr. Fergusson's theory that they were tours de force is so ridiculous that it hardly requires refutation. Other theories have been advanced, such as that these monuments were seats of justice, or popular assemblies, or in some way connected with religious ceremonies, or even astronomical observations; but most, if not all, of such theories have dropped out of memory, as it is to be hoped will soon be the case of Druidic altars. It may, therefore, be assumed that those who think them to be ordinary graves are right. The two other questions are, as already stated, still unanswered. That they were not erected by Druids or their servants is now generally thought, but by some earlier race of whom not even the name is known. All that can be safely inferred from the contents of some of these graves is that they preceded the earliest of Celtic and Roman arrivals. The majority of our South Wales cromlechs have been already figured and described in the Journal. The visit to Fishguard has made known others, but of no great importance as to dimensions and peculiarity. The Pentre Evan Cromlech has, perhaps, with the exception of the Plasnewydd megaliths, been more often and more fully described than any similar monument in Wales. The first notice of it occurs in George Owen's account of Pembrokeshire, which will be found in the second volume of the Cambrian Register, p. 216. It also appears in Gibson's Camden, vol. ii, pp. 758-9, 2nd edition. The manuscript became the property of John Lewis of Manorowen, great-grandfather of Richard Fenton. It was communicated to Edward Llwyd of the Ashmolean Museum, who sent it to Bishop Gibson for his new edition of Camden. Llwyd acknowledges to have received it from Mr. John Lewis. George Owen does not speak of "cromlech" as Druidic or as a temple, as did Sir H. Colt Hoare, but as erected over some distinguished conqueror, or commemorative of an important battle. The late Sir J. Gardner Wilkinson first drew attention to the adjacent stones, which were evidently portions of another chamber. Mr. Longueville Jones, in his account of this monument, thought them part of a gallery attached to it; and, moreover, supposes the present monument to have consisted of several chambers covered by a common mound. There were, no doubt, two chambers touching one another. Sir J. Gardner Wilkinson's objection to Mr. Jones' notion was that the mound must have been enormous, and the entire disappearance of it unaccountable; and then comes the confession, " although I am now disposed to believe that all cromlechs were so covered, it is certainly extraordinary that those of Europe and Africa should not have retained any particle of their coverings." It may be extraordinary, but it is also easy to account for the fact on more grounds than one. The two large upright stones at the south-east he thinks were quite unconnected with the support of the monument; meaning, apparently, by monument, the large capstone; but they may have belonged to an adjoining chamber. The account given by George Owen does not and cannot apply to the stones he mentions. They have vanished long ago. There are, indeed, several long stones lying in different directions in ditches or under hedges, whither they have been rolled to be out of the way. These are worth looking after. Their number and dimensions should be recorded, for they are portions of some chamber or chambers like that which once existed here. But whatever doubts may have been raised as to different theories, there can be none as to this cromlech being the most remarkable in Wales.

Note 1. Arch. Camb., 1874, pp. 71, 72.

Note 2. Ibid., p. 137.

There is an extraordinary collection of similar monuments here on a smaller scale. A group of such exists on Penrhiw, on the promontory of Pencaer. Three of these occur in a line, standing singularly hear one another. The first of these is known as Carreg Sampson [Map], or Samson's Stone, as if some tradition of a mighty conqueror being here buried still lingered; but other instances of a similar appellation still exist. Hence, perhaps, the constant repetition of Arthur's Stone or Coit, or, as in Cornwall, Quoit. So also a fallen menhir in the village of Lockmariaker, in Morbihan, is called "the Stone of the Strong Man." The capstone of this cromlech is about 13 by 11 feet, with an average thickness of 2 feet. The supporting stones have been displaced. The same is the case with the other two cromlechs of the group. In the second one the supporting stones, also displaced, are from 6 to 7 feet long, wrhile the capstone measures 12 feet by 8, with an average thickness of 1 foot. The thinness of this stone shows that the superincumbent tumulus could not have been of any considerable mass. The remains of an adjoining circle are easily made out; but the large number of scattered stones, and the luxuriant growth of fern, make it difficult to determine satisfactorily anything about them. At no great distance is a field called "Pare y Cromlech", a singular name, as such monuments are so abundant in the neighbourhood.

Another instance of the kind occurs at Four Crosses in Carnarvonshire [Four Crosses Burial Chamber [Map]], not far from Pwllheli, where a farm is called "Cromlech Farm",1 and has always been known by that name from time immemorial. Such at least was the statement of a gentleman whose estate is near, and who had long resided on it. It has been described and figured in the Archæologia Cambrensis. It is true that in that locality is not to be found such a number of these monuments as in Pembrokeshire; but there are, nevertheless, many at no great distance; so that the names "Cromlech" and "Parc y Cromlech", thus denoting parcels of land, are to some extent of interest. The dates; however, of such names being given may possibly be partially ascertained by the title-deeds. This cromlech, that gives its name to a field, is described in the official report of the Meeting as partaking more of the "nature of a very large cistvaen than any others, as the capstone, which lies east and west, rests on the supports laid lengthwise, and not upright." As there seems to be no real difference between the cromlech and kistvaen, the unusual position of the supporter is probably due to the materials at hand; but the fact is, these supporters in this case, although very small, are upright, the spaces between them being filled up with horizontal slabs. This monument may, perhaps, be that called "Gillach Goch", described by Fenton as follows: "There is one more remarkable than the rest, a large, unshapen mass of serpentine, 15 by 8, and 2½ thick. Under the edges of it are placed nine or ten small stones embedded in a strong pavement extending some way round. These small supporters are seemingly fixed without any regard to the height, as only two or three bear the whole weight of the incumbent stone." It has been noticed in the Archceologia Cayiibrensis, vol. 1872, p. 138. It is of unusual character in having its capstone supported on a row of low stones, so that none but a very slender man could insinuate himself underneath. The capstone is nearly 14 feet long, 8 wide, and 2 thick; not very different from Fenton's measurement. Those given in the report are: length, 13 feet by 7 feet, lying east and west; "that on the south side being 10 feet long by 3 feet 6 inches above the ground." The more usual position of the capstone is north and south. But there is a slight ambiguity in the description, as "that on the south side" may mean a separate capstone, or part of the one measuring 13 feet by 7 feet. It is, however, possible that the cromlech called "Gilfach Goch" is not the one alluded to in the report, although answering in some respects.

Note 1. Arch. Camb., 1869, p. 138.

Another cromlech is also marked on the Ordnance Map, but being either concealed by the heath, or so low, could not be found in a search made for it in 1865. Nor does Fenton seem to have known or heard of it, for he does not mention it. Mr. Blight, who has given an accurate delineation of Gilfach Goch in the Journal, and who is a short and slight built man, did succeed in getting under the stone, but found nothing but a fragment of flint, which must have been placed there, as there is no natural flint in the district, and it is difficult to imagine that a secondary interment w7as possible under such a stone. Fenton, however, has given us a curious account of it: " On the upper surface of the cromlech are three considerable excavations, near the centre, probably intended to have received the blood of the victim, or water for purification, if, as is the most general opinion, they were used for altars. Its height from the ground is very inconsiderable, being scarcely 1 foot high on the lowest side; and on the other only high enough to admit of a person creeping under it, though when once entered the space enlarges, from the upper stone having a considerable concavity." The earth below is rich and black, which he afterwards ascertained was chiefly the result of fire, as many bits of charcoal and rude pottery have been picked up. A farmer informed Mr. Fenton that two or three years before his visit two spear-heads were found laid across each other, and a knob of metal, suspected to have been of gold. Whether the farmer, knowing the enthusiasm of Mr. Fenton for Druidic mysteries, may have invented the story, or some tradition of such a discovery may have remained to that time, is not known; yet what connection could exist between the spear-heads placed cross-wise, and the knob of supposed gold, is a question which is left for others to answer.

There seems to have been a feeling that the history of cromlechs is not so simple as some think. Thus Bonstetten has brought forward certain arguments to prove that it is not true that the covering up of stone chambers was not unusually the case. These arguments may be reduced to six:

1. That structures which cost such labour and expense could never have been intended by the builders to have been concealed from view.

2. That in the majority of cases no sufficient motive could have existed to induce men to act so foolishly.

3. If such a motive were the clearing of the ground for tillage, then the stones, as well as the soil, would have been removed.

4. The largeness of some of these monuments was such as to render their covering impossible, or so improbable as almost to be impossible.

5. That hundreds of denuded cromlechs have not the least trace of any former covering; and that, too, where there was no apparent inducement to uncover them.

6. That some chambers have walls with round holes worked in them; and these holes, whatever their intention, would have been useless if buried under a mound.

In reply, it may be said that Nos. 1 and 2 are mere suppositions, unsupported by even a pretence of argument. No. 3 is a similar assumption, contradicted by the fact that in many cases the soil has been completely removed, but the stones left. No. 4 is also disposed of by the fact that much larger monuments of the kind than any found in these islands are found in France and elsewhere. No. 5 is a simple assertion that because no trace of the covering now exists, there never was a covering.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Abbot Ralph of Coggeshall describes the reigns of Kings Henry II, Richard I, John and Henry III, providing a wealth of information about their lives and the events of the time. Ralph's work is detailed, comprehensive and objective. We have augmented Ralph's text with extracts from other contemporary chroniclers to enrich the reader's experience. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

The question of holed stones is of a more difficult character. The late Mr. Brash has collected many examples of such holes in these islands, India, and elsewhere. The- double holes in the chamber at Plas Newydd, in Anglesey, are well known; but there is generally such a similarity among them, especially in the Indian examples, that it may be assumed that they are all intended for the same purpose; and that as they did not communicate with the outer air, they might have been intended as a medium of some kind of communication with other chambers in the mound by means of passages. It must, however, be acknowledged that there is a mystery about them which has not yet been satisfactorily cleared up. But whatever the purpose of these holed stones (and there must have been some reason for them), they are no proof that the structures in which they are found were never enclosed. No. 6 argument is that, if so covered up they would be useless; but as they may have been used in some way which we do not at present understand, this argument, like the other five, falls to the ground.

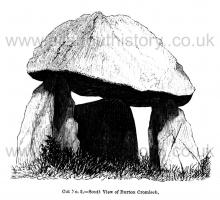

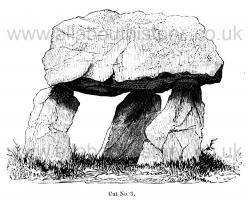

In the volume for 1872, p. 126, are two views of the Burton Cromlech, Pembrokeshire [Hanging Stone aka Burton Burial Chamber [Map]], which has not been so often noticed as others. In 1864 it was used as a small sheepcot, and had been built round with small stones, since cleared away with advantage. The capstone lies north and south, measuring about 11 feet by 9. The capstone is unusually massive, and as far as one example can illustrate it, settles the question of capstones ever serving as altar-slabs. The two excellent illustrations here given are from drawings by Miss Tombs and her brother, of Burton Bectory.

There are two similar monuments not far from Llwyn-gwaer, which, for want of time, were not visited in the course of the Fishguard Meeting; which disappointment, however, was more than compensated by the kindness of Mrs. Bowen, who drew for the Society the sketches Mr. Worthington Smith has given in the two cuts, a and b.

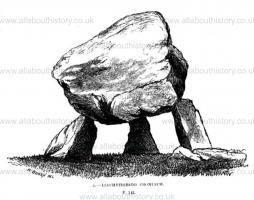

That of A represents Llechytribedd [Llech y Drybedd Chambered Tomb [Map]], or the Stone of the Three Graves. Its capstone, 7 feet 10 inches by 7 feet, and about 4 feet thick, is of unusual thickness. A reverse view, from a sketch by Sir B. Colt Hoare, is given as a vignette by Fenton. There was formerly a fourth stone lying near it, but now lost. This was, no doubt, the stone that closed the entrance, and therefore independent of the capstone.

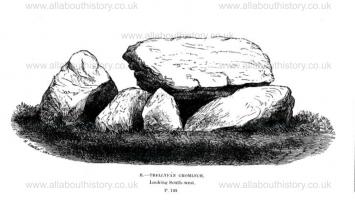

Trellyfan Cromlech [Trellyffaint Burial Chamber [Map]] (cut B) has never been engraved, and is very seldom mentioned even in the most satisfactory guide-books. The capstone has partly slipped on one side, so that it is not certain how far it resembled that of Llechytribedd, which is inclined at an angle. This is so often the case that there appears to be some reason for it; for it generally happens, as in the Newport Cromlech, that the entrance is higher, and more accessible for moving and replacing the slab that closes the entrance. This inclination of the capstone is, however, rather the exception than the general rule, the horizontal position much depending on the shape of the stone.

The cromlech at St. David's Head [St Elvis Farm Burial Chamber, Pembrokeshire [Map]] (see Arch. Camb., 1872, Plate, p. 141) having lost the supporting stone at one end, thus becomes what some consider a distinct class of cromlech, which they call "demi-cromlechs" or "dolmens". Earthfast is also another name for the same class; but these distinctions are already going out of fashion.

The other important South Wales monuments of this class are those of Longhouse [Map] (p. 141), Llanwnda [Map] (p. 137), Dolwylyn, near Whitland, the north and south sides of which are given, p. 136, and are here reproduced; the fallen cromlech at Newton Rhoscrowther (p. 142). All of these, whatever their condition, belong to one class; but it is curious that in two of the central provinces of Corea exist a large group of similar memorials, described by M. Carl in a Report made very lately. His account is as follows: "We saw a curious structure resembling a rude altar, consisting of one massive stone placed horizontally on small blocks of granite, which support it on three sides, leaving the other side open, and a hollow space, some 16 feet by 10, beneath. Many of these quasi altars were standing in the valleys; but although it must have cost immense labour to place these stones in position, no legend was current to account for their existence, except one which connected them with the Japanese invasion at the end of the sixteenth century, when the invaders were said to have erected them to suppress the influences of the Earth (Ti Chi). Whatever their origin, they have been left undisturbed.

The tradition is a singular one, but of little value, except that it shows how completely their real history has been lost. But they bear such a resemblance to our cromlechs that they may be thought to be also burial-chambers with one side (that of the entrance) exposed. M. Carl may not have been learned in such matters, or the extraordinary resemblance must have struck him. The only respect in which they differ is that they are found in the valleys, and not on the higher grounds, as is the general but by no means universal rule in this country. Unfortunately, Mr. Fergusson does not seem to have even heard of them, or we might have expected some mention of them in his Rude Stone Monuments of All Countries.

Enough has been said on the question as to the nature and use of cromlechs; and it is to be hoped that we shall no more hear of their mysterious character, which it was hoped the archaeologists of Fishguard and its neighbourhood would have helped the members of the Association to clear up. As to their builders, and the time of their erection, we have nothing but bare conjecture to help us, whatever that help may be wTorth. But we have had enough of theories as foolish as they are groundless, which will probably soon pass away; not, we trust, to be resuscitated. What charms the omne ignotum have with many, we all know, and hence the many theories on the subject. The views here given have been sometimes called Mr. Barnwell's dictum. If it is his dictum, it has never yet been contradicted, much less refuted.

E. L. Barnwell. Melksham, Wilts. 1884.