Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page.

Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Archaeologia Cambrensis 1864 Page 44 is in Archaeologia Cambrensis 1864.

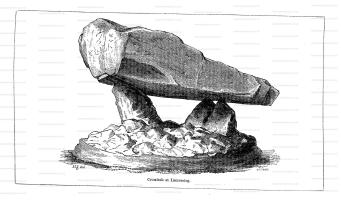

Cromlech At Llanvaelog, Anglesey [Ty Newydd Burial Chamber [Map]].

In 1844 I visited that portion of Anglesey which extends from the Menai to Holyhead, along the south-western shore, in search of early and mediaeval remains; and at that period took a drawing of the double cromlech at Llanvaelog, one of the best in the island. One cromlech was erect; the other by its side, thrown down: or rather, I should say that the two constituted the remains of a large chambered mound,—perhaps of a cromlech with a passage, as at Bryn Celli [Map] in the same island. The cap-stone of that which was erect measured thirteen feet and a half in length by about five feet in depth and width at the thickest part. The cap of the fallen one was broken in two, but when entire it was not less than fifteen feet long. Fortunately this drawing remains in my portfolio; and it shews the importance of preserving memorials of these early monuments, whenever opportunity offers, made with all possible care; for since then the fallen cromlech has utterly disappeared; and the upright one has been so seriously damaged, that its destruction will now be the work of only a few winters, —all through the sheer stupidity of man! I had occasion to pass by the spot last summer, and, on going to renew my acquaintance with this venerable monument, found nothing more remaining than what is represented in the accompanying engraving. An "improving tenant" had come upon the farm. He wanted to repair his walls; and, though the native rock cropped out all around, he found it more convenient to blast the fallen stone, the very existence of which was probably unknown to either the landlord or his agent. Hence the fallen one disappeared. The tenant, however, seems to have been in some degree aware of the importance of the erect cromlech; for he cut a kind of trench all round it, and by subsequent ploughings has left it standing on a kind of low mound. Formerly it stood in a grass field, among gorse bushes, with no wall near it, and only some broken embankments with Anglesey hedges on the top. A few years ago the land came by inheritance, on the death of Lord Dinorben, to the present possessor of Kinmel; and the tenant, desirous of shewing respect to his new landlord, determined to celebrate the occasion with a bonfire. This fire he lighted on the top of the cromlech; and though the stone was five feet thick, the action of the fire and the air split the ponderous mass right through the middle, crossways! Of course this injury was not intended; but it was well known and lamented in the neighbourhood,—for several labouring people mentioned the circumstance to me, and regretted it. As it now stands, the combined action of autumn rains and winter frosts will infallibly enlarge the crack, and will complete the disintegration of the stone. The cap, too, stands now on only three stones, and is in the most imminent danger of coming down altogether; for one of them supports it by an extremely small point, very near one of the sides of the triangle of gravity; and so fine is this point, that it is a wonder how it can withstand the great pressure bearing upon it.

The stones are all of a metamorphic character, containing crystals of quartz, chlorite, and feldspar; almost granitic in texture.

Ten men, with three or four horses and some powerful levers, would repair this cromlech in a single day, and guarantee its preservation for ages. But will they do so?

H. L. J. Oct. 26, 1863.