Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Archaeologia Cambrensis 1869 Page 118-147 Cromlechs in North Wales is in Archaeologia Cambrensis 1869.

A great many of the cromlechs in Wales have already been noticed, and accurate representations of them given in the Journal of the Association. We now proceed to lay before the members a brief mention of some that have not yet been thus noticed, and we commence with those that stand on the estate of Corsygedol in Merioneth. They are all of them in a state of greater or less ruin; but as far as the care of the present owner of the estate can secure them, they are not likely to be still further mutilated or destroyed. There is, however, one easy and simple precaution which will occur to most. Around these cromlechs is a large collection of stones which once composed the carns. If a low wall was built with these stones round the cromlechs, with a small wicket or steps for an entrance, they would be protected from cattle, and more likely to be respected by-visitors and neighbours.

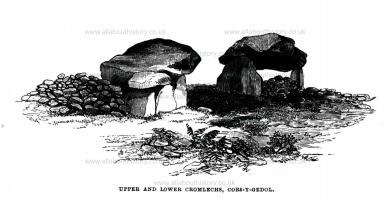

The two chambers [Dyffryn Ardudwy aka Cors-y Gedol Burial Mound [Map]], of which cuts 2 and 3 give faithful representations, are on the right of the main road from Barmouth to Harlech, and not very far from the village school. The lower one (No. 2) has its chamber still perfect, a very unusual circumstance. There may, however, have been a second chamber originally, as the side-walls project nearly two feet beyond the slab that closes the chamber; but as there no traces of such an addition, it is more likely that this projection of the sides is accidental, while the enlargement of the extent of the chamber could not have been considered of importance, otherwise the cross-stone might have been easily put further back. The chamber itself, consisting of six stones, is about 7 ft. long, measured exteriorly, and about 6½ ft. broad. The diagonals of the covering slab are 8 ft. 7 ins. and 7 ft. 3 ins. The supporters rise on an average about 3⅓ ft. above the ground. The entrance seems to be where the side-stones project, and the slab which closes it does not touch the capstone, so that its removal might be effected without danger to the ponderous roof. It faces the east, and is another confirmation of Mr. Lukis' statement. The whole dimensions of the structure are moderate enough; but the preservation of its chamber gives a peculiar value to this example. Around it are thickly strewn the stones which once composed the carn under which it was covered; and as the same thing occurs in the cromlech near it, and as the two monuments are hardly ten yards apart, there can be little doubt but that both of them were originally covered up by one and the same mound of stones, for there would not have been sufficient space to have permitted two carns, if they were to be built of sufficient height and size to cover each cromlech.

The upper cromlech (No. 3) is larger, but not so perfect as No.1. All the supporters on its south side have vanished. Measured on the outside, the length of the structure is nearly 14½ ft, and its breadth about half the length; thus presenting a contrast to the smaller chamber, which is nearly square. The diagonal measurements of the capstones give 13 ft. 2 ins. and 12 ft.; the maximum breadth being 9 ft. and the average thickness 2ft. The height of the tallest supporter is 4½ ft.

The position of the two cromlechs is given in cut No. 4, in which it will be seen that the upper one is represented in a different point of view from the figure in cut 3. On the edge of one of the uprights of the lower cromlech is a series of lines, or rather grooves, which has an exceedingly artificial appearance; and if artificial, the appearance of being as old as the cromlech. But as rocks exist in the locality, marked with the same kind of grooves, it is mot improbable but that the grooves under consideration are the effects of natural causes.

Both in the field in which are the cromlechs, and in the adjoining one, are innumerable carns and remains of carns, which extend down the slope nearly to the sea-shore. A reference also tothe Ordnance Map of the Vale of Ardudwy, from Barmouth to the Two Traethau, will shew, from the number of cromlechs and fortified posts (and there are many of the latter not given), that the whole district must have been densely inhabited at a very early period. Even after the destruction of such monuments, which has been going on for centuries, the number of those remaining, especially the cromlechs, is remarkable; so that there are, perhaps, few parts of the Principality where they are to be found in equal numbers and importance.

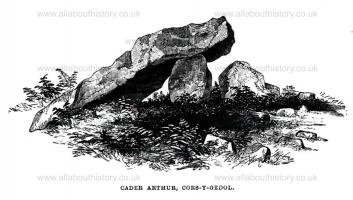

A little above Corsygedol Mansion is a third cromlech [Cader Arthur aka Cors-y-Gedol Burial Mound [Map]] (No.5), of which a representation is here given from a most accurate drawing by Miss Colville of Corsygedol. Here also are the remains of the carn which once covered it. The capstone has been dislodged, so as to leave one end resting on the ground; but even when in position, the cromlech must have been somewhat lower than usual, and certainly of moderate dimensions. Little can be made out of the original chamber, except that it stood east and west. A little further on, to the left hand, and partially embedded in a stone wall, are the remains of a similar monument. It should be noticed, moreover, that the ground, to a considerable extent, adjoining these monuments, contains an immense number of circular and rectangular enclosures, which appear to have contained within their walls the inhabitants of a large settlement. A little beyond this collection of dwellings stands also the strong work of Craig y Dinas, which protected the pass in the mountains against enemies from the east; and served as a place of refuge to the inhabitants below, if attacked from the sea-side. It is clear, therefore, that Corsydedol stands almost in the centre of an ancient and numerous settlement; and as there is some doubt as to the origin of the name, one version being that Gedol is the name of a man, he may have been one of the descendants of that settlement who have left behind them such numerous traces of themselves, not merely in their graves but in their dwellings, enclosures, and even their stronghold in case of exigency.

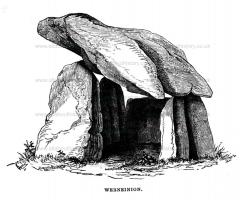

In the parish of Llanfair, on a small farm called Gwern Einion, is another cromlech [Gwern Einion Burial Mound [Map]], of larger proportions than those already mentioned. It is, for a Welsh cromlech, in a tolerably perfect condition, and was lately used as a pigsty. There is a large quantity of stones heaped up around it, which may, perhaps, have been the remains of the carn; but this is not quite certain, as the place might have been considered convenient to receive the stones when cleared off the land. (Cut No. 6.)

Not far from this spot is a remarkably fine maenhir [Gwern Einion Standing Stone [Map]], built in the middle of a high wall; over which it towers, and presents a conspicuous mark against the setting sun. This stone, local authorities say, was originally dedicated to the sun; and when it was judged expedient to burn a human victim in honour of that luminary, the unfortunate sufferer was secured by iron chains to the stone. The lower part of the stone is now embedded in the wall, so it is not easy to make out the traces of the fire; which otherwise would, no doubt, be discovered, and believed by the peasants of the district. There is little doubt that many other monuments of the same character have once existed in this district, as here and there fragments of them may be found in the stone walls which divide the enclosures. There is also reason to suppose that most of the stones of which the carns were formed have found their way to the same destination, for the builders of these walls have ascertained by experience that the stones taken from such early remains, are much more suitable for their purpose than any others they can find. Whether this is exactly the case in this part of Merioneth, was not ascertained by personal inquiry; but such, at least, is the acknowledged fact in the higher lands of Denbighshire.

There are other cromlechs in this part of Merioneth, which, together with the curious remains at Carnedd Hengwm [Map], must be reserved for some future notice.

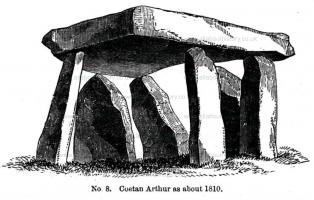

Not far from Criccieth, near Ystym Cegid [Ystum Cegid aka Coetan Arthur Burial Mound [Map]], are the last remains of what must have been, in Pennant's time, an interesting group of three cromlechs "joining to each other." If by these words he meant that they actually touched each other, the tumulus that enclosed them must have been of gigantic proportions. Gigantic as it was, it had so completely disappeared in Pennant's time that he does not even appear to have suspected its existence. He merely speaks of the three structures as probably "memorials of three chieftains slain on the spot." Of these cromlechs, however, two have entirely vanished; and the remains of the third are small and insignificant, consisting of what have been four supporters of very moderate dimensions, and the capstone, of a triangular form (cut No. 7); its greatest length being between fourteen and fifteen feet, and its greatest breadth twelve and a half. Its thickness, however, has not the usual proportion, being unusually thin and slight, It is only very lately that this covering slab was dislodged from its original position by some masons who had taken a fancy to one of the supporters for some building purpose; and it is very probable, unless proper precaution is taken, that what still remains of this triple group will vanish, and not leave even a trace of itself. The removal, however, of two of the three must have taken place some fifty years ago, and not long after Pennant's visit, for Pugh, in his Cambria Depicta, in the early part of the present century, drew the monument as he found it, and as is here given from his drawing.

(Cut 8.) From this it will be seen that it was tolerably perfect when he saw it, except that, unless the intervals between the uprights had been originally filled up with rubble, some of the uprights must have been wanting. It was, however, at that time used as a cow-house by the farmer, and the vacant spaces were then filled up with walling, but most probably by the farmer himself. The present remains, exclusive of the capstone, are three upright supporters, one lying under the cover,and another in the ditch. The tallest of the upright ones is 5 ft. 6 ins., and the prostrate one, 6 ft. 9 ins. The chamber originally was about 10 ft. by 9. A considerable number of small stones are amassed around it; but whether merely collected there to be out of the way, or the remains of the original carn, is uncertain. In the present mutilated state it is not easy to determine what the direction of the chamber was. The entrance, however, could not have been on the south or west side; and although it may have been on the north side, it appears to have been on the usual side, namely the east. It is only known by the peasants as Coetan Arthur [Map]; and if questioned, they appear to have never heard of a cromlech or a Druid's altar. Nor is this ignorance confined to this particular district, for it appears to exist in most other parts of Wales.

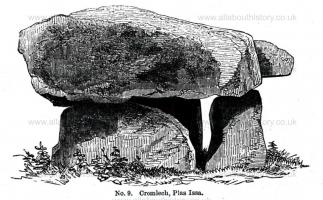

At no great distance is another cromlech [Rhoslan Burial Mound [Map]] (cut No. 9), of a very different character from the last, in having a capstone of unusual thickness, 3¼ feet, if the other proportions of the stone are taken into consideration. It stands due east and west; the eastern entrance being formed by two uprights, on which the capstone rests, and which, therefore, could not have been removed for any subsequent interment. The opposite end of the capstone is supported by only one upright; but whether this was the original arrangement or not, must be mere speculation. The structure at present consists only of four stones, without reckoning the cap, namely the three supporters and one long slab which forms the northern side of the chamber, the side given in the cut. The whole of the southern side has been removed. It is situated on a farm called Plas Issa, near Criccieth.

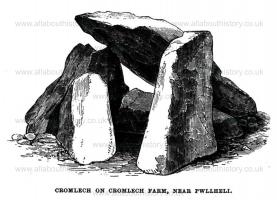

Close to the village of Fourcrosses, near Pwllheli, is a cromlech [Four Crosses Burial Chamber [Map]] which is remarkable for giving the name of "Cromlech" to the farm on which it stands. Inquiry has been made of gentlemen who have been for many years acquainted with the locality, and the result is the information that from time immemorial the farm has never been called by any other name but its present one of Cromlech. Now, as is well known, there has existed, and still does exist, much doubt concerning the real origin of the name. Rowlands, in his Mona Antiqua (p. 47), says "these altars were, and are to this day, vulgarly called by the name of cromlech." He gives two reasons for the name, one of which is that it is a mere description of an inclined stone, crom and llech; but as some of the capstones of cromlechs are not so inclined, Rowlands seems to prefer the second explanation, namely that the name was, like many other names, imported from Babel, and was originally cceremlech, that is, a devoted stone or altar! If Rowlands's statement, that these monuments were ordinarily known as cromlechs in his time, is correct, it is very curious that the name should have been lost, as a general rule, among the common people. That it was, however, a correct statement seems to be confirmed by the name being given to a farm at a period beyond memory. No assistance is likely to be rendered by any old deeds connected with the property, which was once an outlying portion of the Corsygedol estates.

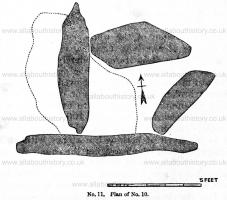

The cromlech itself (cut 10) is remarkable also as shewing indications that the chamber was not entirely composed of the usual slabs, but that portions of the walls had been built up of dry rubble. Allusion has already been made to the entrance of the chamber being frequently thus built, or in some cases entirely of rubble. Dr. Griffith Griffith, during a late visit to Algiers, saw several cromlechs which had considerable remains of this rude masonry still remaining. On referring to the plan (see cut No. 11) it will be seen that the chamber is of unusual form, for the slab which partially closes the eastern side is not parallel to the opposite side. It appears to be in its original place, but still it is not impossible that it has been subsequently shifted to its present situation. But however this may be, it is so low that to complete the eastern enclosure another slab or dry masonry must have been added so as to reach the capstone. The latter has been partially dislodged, and does not now cover the chamber; which, if the eastern stone has been since shifted to its present oblique position, was nearly a square, having its entrance, as usual, on the eastern side. Although this monument is not of large dimensions, yet it is probable, from the entrance having been partly of rubble, that it has been used as the place of burial on more than one occasion. There are no traces whatsoever left of the tumulus.

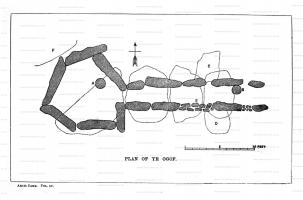

None of the cromlechs that have been briefly mentioned seem to have traces of galleries leading to the chamber. This, as is well known, is one of the marked distinctive features of sepulchral chambers in Britany, as contrasted with those of this country. In the former country they are by no means uncommon; in the latter, particularly as regards Wales, they are extremely rare. Allusion has been already made to the gallery connected with the three chambers near Capel Garmon [Map]. Through the courteous kindness of Capt. Lukis we are enabled to present a copy of the plan made by that gentleman, accompanied with careful and accurate measurements of details (cut 12), of the chamber of Bryn-celli Ddu [Map], or, as it is called in the Ordnance Map Yr Ogof, or the hole or cave. It still retains some portion of the original carn, but is more remarkable from its having the greater portion of the original gallery leading to the chamber, in a tolerably perfect state. A view of the exterior of the chamber, showing the remains of the cairn and gallery together with an accurate description of the whole monument will be found in the Archæologia Cambrensis of 1847 (p. 3). Rowlands, in his Mona Antiqua, merely describes the remains of two carns near each other, one of which had been almost in his time entirely removed, and the other had been broken and pitted into on one side. "Two standing columns" are also said to exist between the two carns. (Mona Antiqua, pp. 93, 100.) An extremely rude representation is also given, which represents the carns as composed of nothing but stones, without any admixture of earth, which was not the case. As Rowlands says nothing about the gallery, it is more than probable that although the carn had been "pitted into" on one side, the gallery had not been discovered,— much less the chamber. While Pennant described it, one of the carns had vanished. At least he writes as if only one existed at the time. The upright stones are also passed over without notice, and were also probably no longer in existence. On the other hand, the late Miss Lloyd, in her account of the parish of Llanddeiniol Vab, in which the monument stands (see History of the island of Mona, p. 221), says, "At Bryncelli are some traces of large carneddau, where two upright stones are still standing."

But her not mentioning the chamber and gallery, the account of which by Pennant must have been known to her, would tend to show that she merely obtained her information from Rowlands, and had forgotten Pennant's description. Her History of Mona was printed in 1832. Pugh, in his Cambria Depicta, published in 1816, appears to have visited the chamber, but does little more than repeat what Pennant had previously stated.

The statement, as given by him (vol. ii, p. 272, ed. 1784), is as follows: "A few years ago, beneath a carnedd similar to that at Tregarnedd, was discovered, on a farm called Bryncclli-ddu, a passage 3 ft. wide, 4 ft. 2 or 3 ins. high, and about 19½ ft. long, which led into a room about 3 ft. in diameter and 7 ft. in height. The form was an irregular hexagon, and the sides were composed of six rude slabs, one of which measured in its diameter 8 ft. 9 ins. In the middle was an artless pillar of stone, 4 ft. 8 ins. in circumference. This supports the roof, which consists of one great stone near 10 ft. in diameter. Along the sides of the room, if I may be allowed the expression, was a stone bench, on which were found human bones, which fell to dust almost at a touch." Such is the statement; but unfortunately it is not certain that Pennant speaks of having seen what he decribes. He did visit Tregarnedd, in Llangefni parish; and his account of the chambered mound, which gave its name to the farm, seems to have led him to mention the somewhat similar chamber at Bryncelli-ddu. He may, however, have seen it on some former occasion; but whether this is the fact or not, it may be assumed with some degree of certainty that he would not have thus minutely described the chamber if he had not assured himself of the correctness of the information which had been given him.

This propping the capstone is very remarkable; but another example of such supplemental support may be seen in the great cromlech at Plasnewydd [Map], the enormous capstone of which seems to have made it necessary to place an additional supporter at an angle so as to meet the outward thrust. This, however, must have been done before the chamber was covered up by its mound; whereas in the case of the Bryncelli-ddu chamber, there is no reason why the pillar might not have been introduced after the entire completion of the monument, carn and all. Capt. Lukis states that there is a second pillar-stone at the eastern end of the gallery, which, strange to say, seems not to have been noticed by other observers; not even by the author of the excellent account given in the Arch. Camb., before mentioned; and is certainly not there at present. It is evident that, to whatever use the pillar in the chamber was applicd, that in the gallery must also have been put to the same; but what that use was, is doubtful, according to the opinion of Capt. Lukis, who has kindly placed at the service of the Association his notes on the subject:

"I have had another day at the cromlech of Yr Ogof, or "the cave"; and on the right side of the chamber, near the singular stone pillar which is within the area, I found a rude pavement of flat slabs; and immediately beneath it was a thick bed of small beachy pebbles, about 2 ft. in thickness,—at least the side-props seemed buried in it to that depth.

During the operation I found no pottery; but a few fragments of lead, which I consider as having been thrown there accidentally; and a good deal of charcoal, a broken flint-knife, a javelin-head, and some few bits of human bones.

"I then measured the extraordinary stone-pillar, which was in a slanting direction towards the south, and I found it to be exactly 9 ft. in length, with a circumference in its thickest part (for it tapers upwards) of 14 ft. 10 ins. This leaning pillar bore evidence of its having been disturbed at the base, on the southern side; but I do not conceive that when in its proper upright position, it could have touched the under surface of the covering stones.

In reasoning on the singularity of this pillar within the principal chamber, so very unlike the other props of construction around the place, it cannot be considered to be for the purpose assigned to stone-pillars, as supports, which are sometimes found in other cromlechs. In the structure of Déhus, in the island of Guernsey, the rude pillar beneath the second capstone was evidently placed therein to support a flaw or crack which was found to endanger that covering stone. Again, in the cromlech at Carnac, in Brittany, the capstone was found to be too short, and it became necessary to support it by an additional side-prop. Other cases might be adduced where internal supports have been placed; but in all these instances the intention and the reasoning of the cromlech-builders are clear and evident. All these supports are equally rude, unwrought props for a necessary purpose.

At Yr Ogof we find a pillar with a regular abraded surface, almost polished in some parts, and gradually reduced upwards. The character of this pillar is so different from those on record, that we are forced to assign some other reason for its introduction into the main chamber.

"In the accompanying plan of the structure it will be seen that another abraded pillar stands at the eastern end of the avenue covered way. It is more rude and irregular than that in the chamber; and it stands near a small side-cist, which appears to be an addition to the chief cromlech. The character of these two pillars must be considered as having a design entirely different from those we have discovered in other cromlechs.

"To enter largely into the religions which prevailed over the world in the infancy of man, would lead us to a lengthy chapter far beyond the limits of this Journal; but we cannot avoid being struck by the strong religious feelings which the cromlech-builders possessed in cone triving these strongholds for the security of their dead bodies. I can only say that the pillars at Yr Ogof assimilate greatly with the styles of the Hindoo, although there may be some deeper meaning in placing them within the chamber of the dead."

Then follows a sketch of an altar erected to Siva or Mahades, which was found in a grove not far from Allabahad, on which were placed five stone celts (now in the possession of Capt. Lukis); and as those implements are so frequently found in our own cromlechs and cists, he thinks there may be some connexion of Eastern metaphysical speculations with those which may at one time have prevailed in our country. The altar is rectangular, built up of square stones surmounted by a thin slab, from the centre of which rises a short stilus against which leant the five celts, although only three of them still retained that position at the time of the visit.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, a canon regular of the Augustinian Guisborough Priory, Yorkshire, formerly known as The Chronicle of Walter of Hemingburgh, describes the period from 1066 to 1346. Before 1274 the Chronicle is based on other works. Thereafter, the Chronicle is original, and a remarkable source for the events of the time. This book provides a translation of the Chronicle from that date. The Latin source for our translation is the 1849 work edited by Hans Claude Hamilton. Hamilton, in his preface, says: "In the present work we behold perhaps one of the finest samples of our early chronicles, both as regards the value of the events recorded, and the correctness with which they are detailed; Nor will the pleasing style of composition be lightly passed over by those capable of seeing reflected from it the tokens of a vigorous and cultivated mind, and a favourable specimen of the learning and taste of the age in which it was framed." Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Now, although any opinion on cromlech questions emanating from a member of the Lukis family will be received with due consideration and respect, yet serious objections to his views as regards the present case will at once suggest themselves to most minds, as they have probably occurred to him himself. 'L'he principal reasons given by Captain Lukis, that these pillar stones were not intended for props, are, that the other arranaements for giving additional support which have come under his cognizance elsewhere are totally dissimilar, that these pillars have been curiously abraded and almost polished, and lastly, that the one in the chamber is too short to have reached the under surface of the capstone. The last of these objections is easily removed; for even supposing that the level of the floor is the original one, yet it would be more easy to fix by means of wedges a prop which is rather shorter than the space between the ceiling and the floor. The same thing is done every day, when it is necessary to give the same kind of support to the beam which supports the upper part of the wall of a house while the lower part is being removed. The props are more securely and efficaciously applied by means of wooden wedges driven underneath them. It is true that when the lower wall is replaced, the props are removed, but the principle is the same. Stone wedges would have been of course used instead of wooden ones, and even according to Captain Lukis's account there appear to be certain indications at the base as if the stone itself had been curtailed at this end; and it is not improbable this appearance may have been caused by the action of the stone wedges. It is curious that one of the pillar-stones has been worked, and even polished. This polishing might indicate that it is of later date than the chamber itself; and as it is certain, as will be presently seen, that this has been the burial-place of more than one, and may have been in continued use for generations, it may be fairly suggested that, in course of time, the security of the capstone of the chamber being doubtful, the precaution of thus propping it up was taken, long after the first construction of the chamber. But whether these replies to Captain Lukis's objections are considered satisfactory or not, there is still the evidence of Pennant to be set aside, as regards the use and object of the pillar. In addition to all this, it might fairly be asked, is there any instance known of anything like a stylus, found in any of the chambers have of late years been carefully examined by competent persons, as is the case more particularly in Britanny. Nothing, we believe, of the kind has been ever found or even looked for. It is true that magnificent discoveries of stone implements have been made; but these cannot be considered as in any way connected with any Eastern or other mysticism, being simply the implements and ornaments placed by the body for use in its future state of existence; or, when they are found purposely broken, as is frequently the case, simple tributes of affection and respect, as if such articles were too precious to be ever used again. Independently, therefore, of what Pennant has told us, most will probably consider these stones (if there are two) as simple pillar-props, and in no way connected with any religious or other superstition.

No traces remain of the stone bench once running round the chamber, on which were said to have been placed bones, which crumbled soon after their discovery. Unfortunately, no record of the opening of the chamber has been preserved, and the account given by Pennant does not intimate whether the bones had been burnt or not.

The gallery which led to the chamber, measured in 1847 about eighteen feet, while in Pennant's time it was nearly twenty feet. As, however, he does not allude to the two side cists or small chambers on each side of the eastern extremity of the gallery (see Plan No. 12) it is likely that he did not examine. the structure himself. They may, however, have as easily escaped his notice as they seem to have done that of the writer in the Archaologia Cambrensis. The fact is, that the traces of them, especially of that on the south side of the gallery, are so faint that they are with diffculty made out by an unpractised eye. By some its very existence is doubted. Some thirty or forty years ago, however, one of the servants at Dinam remembers playing up and down the then tolerably perfect carn with his playfellows, the boldest of whom would occasionally enter the chamber itself. His impression is that these chambers existed as is laid down by Captain Lukis in his plan.

These additional chambers prove beyond doubt, that this carn (and probably the other which once stood beside it) was one of the burial-places of the district for a considerable period. Miss Lloyd mentions, in confirmation of this, that there were numerous remains of cromlechs in the adjoining fields. We have innumerable proofs how constantly the burial-places of the earliest races were called into requisition by succeeding races, so that centuries, in some instances, have intervened between the earliest and latest deposits. Unfortunately, no record has been kept of the remains found of the Bryncelli carns, and but for the accidental preservation of the ruins of one of them, no evidence at all of secondary interments would have existed.

That such was the practice in Wales, as elsewhere, admits of little doubt, although the general destruction of monuments of this class has left so few means of proving it. Nothing,however, is more natural, and therefore more probable, than that men would make use of convenient receptacles for their dead, which they found ready made for them, rather than (except under especial circumstances) undertake the cost and labour of constructing such mounds and chambers. Although, therefore, there is no actual necessity that proofs of such a practice should be brought forward, as will be found collected in Ten Years Diggings, yet the existence of the side chambers at Bryncelli is of some importance as confirming what might have been concluded from à priori reasoning.

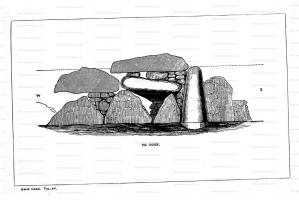

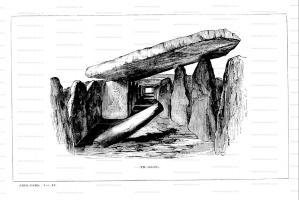

The accompanying views of the interior and side view (Nos. 13 and 14), are also from the pencil of Captain Lukis, and will convey a most accurate notion of the character of the existing structure to those who have not had an opportunity of examining the original. The whole is surrounded by a wall erected many years ago by the late Mr. C. Evans of Plas Gwyn, but for whose interposition, it is probable, that the whole would have been by this time swept away. As already mentioned, living men remember the present ruin a high mound of earth and stones overgrown with blackthorn, the sloes of which they gathered in their younger days, so that the work of destruction must have gone on with activity, as it is at least a quarter of a century since Mr. Evans came to its rescue and saved it from annihilation.

E. L. BARNWELL.