Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Archaeologia Cambrensis 1874 Pages 59- is in Archaeologia Cambrensis 1874.

South Wales Cromlechs

The Pentre Evan Cromlech [Map], near Newport, in Pembrokeshire, may be said to hold the same position among similar monuments in South Wales as the Plas Newydd [Map] one occupies in the northern portion of the Principality. This latter being so much easier of access, and close to the ordinary route of visitors, is probably more generally known than its southern rival. It has, moreover, been more frequently and more fully described and illustrated from the time of Rowlands to that of the Hon. W. O. Stanley of the present day. Rowland's notice is, however, of little importance (p. 94, edition 1765.) Pennant is fuller and is accompanied with a fair representation of the group (vol. ii, p. 246, ed. 1784.) Gough has merely repeated Pennant's account. Angharad Llwyd, in her History of Mona, quotes from her father's papers, and as he was the companion and almost partner of Pennant in his Welsh excursions, she adds little to the published accounts. The same may be said of the notice of this monument in the Munimenta Antiqua, a work of no real value, in spite of its numerous illustrations. Mr. Stanley's notice and illustrations of it, in his account of the great chambered mound near it, and which adds so much to the interest of the Cromlech, is the latest and most complete, and will be found in the Archeologia Cambrensis of 1870. Other accounts exist, but are little more than repetitions of what is familiar to the majority of readers.

The Cromlech of Pentre Evan, if it has not been as fortunate as its northern rival as regards descriptions and illustrations, has at least the advantage of having been noticed by the Pembrokeshire antiquary George Owen, who lived nearly two centuries before Rowlands' time. Sir Richard Colt Hoare visited it, probably in company with Fenton the author of the Tour in Pembrokeshire, as he drew the view of the cromlech which appears in Fenton's book. His notice of it, however, in his edition of Baldwin's Itinerary, is singularly brief. All that he tells us is as follows: "The cromlech, or temple at Pentre Evan, surpasses in height or size any I have yet seen in Wales, or indeed in England, Stonehenge and Abury excepted." The engraving does not accurately represent the monument.

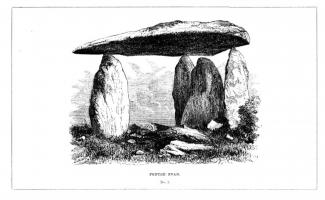

Another view was published in The Graphic and Historical Illustrator, a short-lived periodical started for popular use, and by the late Edward W. Brayley. This view was executed from a drawing of Dudley Costello, taken in 1832, and was taken nearly from the same point of view as that of Hoare, and is not more correct. The illustration (cut No. 1) that accompanies this notice is from a photograph, taken also on the same side as were the two above mentioned engravings, but somewhat nearer the single stone that supports the end of the capstone.

A brief notice of this cromlech also will be found in the Archaeologia Cambrensis of 1865, p. 284, and 1872, p. 129, where is a small but faithful view taken from the north-east or opposite side to the above mentioned view; but even this hardly does justice to the original. A fuller account was also published by Sir Gardner Wilkinson in the Collectanea of the British Archaeological Association. A diminutive view of the rear of the capstone accompanies the notice, and has been reproduced on an enlarged scale, as useful in showing the positions of the two stones, which are the last remains of an anterior chamber. One writer, indeed, has introduced a mention of this cromlech, accompanied with a copy of the little cut in the Archaeologia Cambrensis, in that extraordinary book entitled the Rude Stone Monuments of all Countries, their Ages and Use. According to this authority, the age of our principal megalithic monuments in England and Wales is a and they are mere monuments commemorating the twelve battles won by Arthur as given in Nennius. One very decided confirmation of this theory, as Mr. Fergusson thinks, is the singular fact that the great cromlech on Bryn Cefn in Goweris named after Arthur, and is the only stone so named, as far as he has been able to ascertain; whereas there is hardly a monument of the kind (the Pentre Evan one included) that is not assigned to Arthur.

But as other stone monuments like those of Pentre Evan and Plas Newydd have not been thus explained, with singular courage (for he evidently has not examined either of them) he says, speaking of the former of the two, "the supports do not and could not form a chamber. The earth would have fallen in on all sides and the connexion between the roof and the floor been cut off entirely, even before the whole was completed." Of the Plas Newydd monument he states, with no less boldness:— "Here the capstone is an enormous block, squared by art [which is not the fact] supported on four stone legs, but with no pretence of forming a chamber. If the capstone were merely intended as a roofing stone one a third or fourth of its weight would have been equally serviceable, and equally effective in an architectural point of view if buried" (p. 169). Therefore, as these were not chambers they must have been erected for some important purpose, and this purpose Mr. Fergusson has discovered was the exhibition of the powers and skill of the architect. "These stone men best understood the power of mass. At Stonehenge, at Avebury, and everywhere as here (in Plas Newydd) they sought to give dignity and expression by using the largest blocks they could transport or raise, and they were right, for in spite of their rudeness they impress us now, but had they buried them in mounds they neither could have impressed us nor their contemporaries" (Rude Stone Monument p. 169).

Such monuments, therefore, and especially these two particular ones, are simply memorials of the architectural skill of the stone men, or, to use the language of the discoverer of this strange fact, tours de force.

Such unqualified nonsense has long since been completely disposed of, nor would have been alluded to now, but that this identical cromlech seems to have had a large share in the production of the absurd theory; for: it is not even allowed by Mr. Fergusson a place among the so-called free-standing dolmens, the existence also of which, as original structures, few persons credit, in spite of the authority of M. Bonstetten. Mr. Fergusson states, as if he had seen the monument, that it never could have contained a chamber, whereas if he had taken the trouble to go and look for himself he might have found the unquestionable proof not only of one but of two chambers. We may, therefore, leave these tours de force and their inventor as not worth further notice.

From the rocky nature of the ground, as well as from the large size of the existing remains, it has been more than once asked, whence could a sufficient quantity of earth or even stones be collected so as to envelope such a mass. To cover up even the present ruins would be no easy matter, and the original monument was probably twice as large as at present. Even Sir Gardner Wilkinson has been staggered at this supposed dithculty. But not only does the very character of such structures imply that they must have been covered up, or were at least intended to be so, but the men could not probably have lifted up such a mass as this particular capstone, unless the chamber proper had been previously buried in soil to the top of the side walls, so as to admit of the mass being rolled up on an inclined plane. This having been properly placed, the completing the tumulus must have been a comparatively easy matter. It is singular, however, such a question should ever have arisen or that the universal covering up of such chambers could be so long denied, or even seriously doubted, while there are in existence so many remaining examples of mounds large enough to hide a dozen such cromlechs, and that too in districts as bare and unpromising as the hillside of Pentre Evan.

As already mentioned, the first notice of this cromlech occurs in George Owen's account of Pembrokeshire, and Fenton has given the extract relating to it as follows:—

It is a huge and massive stone mounted on high, and set on the topps of three other high stones pitched standing upright in the ground, which far surpasseth, for bigness and height, Arthur's Stone [Map] in the way between Hereford and the Hay [probably the Bredwardine cromlech, figured in the Archeologia Cambrensis, 1873, p. 275], or Lech yr Ast neere Blaenporth in Cardiganshire, or any other that ever I saw, saving some in Stonehenge upon Salisburye Plain, called Choree Gigantum, being one of the cheefe wonders of England. The stones whereon this is layd are soe high that a man on horseback may well ryde under it without stowping; and the stone that is thus mounted is eighteen foote long, nine foote broad, and three foote thick at one ende, but somewhat thinner in the former; and from it, as is apparent, since its plasing, there is broken off a piece of five foote broade and ten foote long, lieing yett in the place. The whole is more than twenty oxen would draw. There are seven stones that doe stand circlewise, like in form to the new moon, under the south end of the great stone, and on either side two upright stones confronting each other. Doubtless it was mounted long tyme ~ sithens in memorie of some great victorie, or the burial of some notable person, which was the ancient rite; for it is mounted on high, to be seene afar off, and hath divers stones round it, set in manner much like to that which is written in the first Book of Maccabees, cap. xiii. [See vv. xxvii, xxviii, for a description of Jonathan's tomb built by his brother Simon.]

The good old Pembrokeshire antiquary appears to have had none of the Druidical fancies connected with these and similar stones, which long after became so popular, and which even men like Hoare and Pennant adopted. Hence, after giving this extract of George Owen, Fenton talks of "expatiating over this scene of Druidical mysteries," although he seems to adopt G. Owen's conjectures, as he passes over them in silence.

The seven stones that stood circlewise, like the new moon, at the south end of the great stone, were evidently connected with the original mound. He does not unfortunately state how distant they were from the end of the large stone. If they were near they were the remains of the base of the tumulus. If at a moderate distance they were probably the monoliths set at intervals round the tumulus, as if marking out the sacred ground. The two upright stones confronting each other were no doubt portions of the side walls of the chamber. In the view given by Fenton a large stone no longer in existence is represented, and as far as can be judged from the drawing it may easily have been one of the two stones seen by George Owen. In the same view several smaller stones are introduced, which have since been cleared away, but they have much the apheasice of being the remains of the carn or tumulus.

In the able account of the cromlech by Sir Gardner Wilkinson, already alluded to, we read, "Camden states that the Pentre Ifan Cromlech (as he prefers to call it) stood in the midst of a circle of rude stones ‘pitched on end,' the diameter of the area being 50 feet, but this is an oversight, for Camden does not even mention the monument. The extract given as from Camden is the contribution of some correspondent of Bishop Gibson, who (if Fenton's extract is correct) has erroneously quoted George Owen. If the correspondent describes what he saw, it is singular that G. Owen mentioned only seven stones, and omits the important fact that the chamber or area under the stone was neatly flagged." (See Gough's Camden). If the latter was a fact, it is the only recorded instance of a paved chamber in these islands, although such pavements are still in existence in Brittany. It is not impossible that George Owen may have spoken of seven stones only in a half moon as being the most important ones of the circle. The probability is that Gibson's correspondent is correct as to the circle. How far his statement of the neatly paved area is correct, is perhaps not quite so certain.

The accompanying engraving No. 1 is from a drawing by Arthur Gore Esq., from a photograph taken nearly from the same point of view as that from which Sir R C. Hoare made his sketch. It will be seen that the capstone does nct touch the central one of the three, so that it rests only on three SHores, and this was probably the original number. Had other stones supported it, they would have been difficult to remove, and would probably have been preserved By a reference to the ground-plan, etc. (slightly enlarged from that given by Sir Gardner Wilkinson), it will be seen that the central stone stands at right angles to its companions, so that this end of the chamber is made up of its breadth and the thickness of the other two stones; in all 5 feet 8 inches. The greatest breadth of the stone at the opposite end of the chamber is 4 feet 9 inches, so there is about a foot difference in the breadth of the ends of the chamber,—a circumstance which strongly confirms the supposition that there was never more than one supporting stone at the north or narrower end of the chamber. The side walls of the ber have entirely vanished, but were no doubt composed of the ordinary materials, namely, large slabs and dry walling where required. The in thus enclosed running nearly north and south, and in that respect contrary to the more usual rule of east and west, is 10 feet long and nearly 8 feet high. Sir Gardner Wilkinson makes the breadth 9 feet 4 inches, thus making the chamber almost square; but this can hardly be correct if the breadth of the capstone is the same, for it must have overlapped the side-walls.

The arrangement of the three stones forming the south side of the chamber does not appear to have attracted attention, but there has evidently been some special reason for its peculiararity. The southern end of the chamber might have been formed of two slabs if placed in the same way as the middle one now is. By referring to the plan it will be seen that the middle one is placed at right angles to the other two. Nor was it probably an accident that it is just too short by a couple of inches to assist in supporting the capstone; for it seems that this fact would enable the middle stone to be removed, if necessary, without endangering the whole structure. It was necessary to have at least two supporting stones at this end of the chamber, and if the wll now standing had been placed in the same line they would have occupied too great space for that end of the chamber. The two exterior ones are, therefore, placed at right angles to the central one, making the total breadth of this end under six feet, whereas had they been placed on a line it would have been at the least ten feet seven inches, supposing that the stones all touched one another. If two stones had only been used, neither of them, as supporting the capstone, could have been removed, and no entry possible. The difficulty was then got rid of by so placing the outer stones that their thickness not their breadth, together with the middle one, made up the necessary breadth.

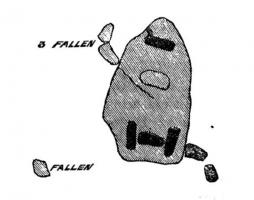

Another advantage gained was that the projecting portions of the two outer stones could serve as part of the side walls of the chamber, which was about six feet broad, although Sir Gardner Wilkinson speaks of the area being nine feet four inches broad. If he means by area the ground overshadowed by the capstone, he does not seem to have taken into account the rapidly diminishing space towards the northern end. He speaks also of the capstone being nine feet four inches broad, but this can only mean the maximum breadth in one particular part, nor does he appear to have taken into consideration the existence of a chamber at all, the dimensions of which are easily ascertainable; for if two stones were placed at the northern end, similar to those at the opposite one, and for which there is just room so as to be covered by the capstone, they would be exactly opposite the two at the south end, and thus the walls would enclose a chamber of ten feet by six. A chamber of such dimensions is unusual, but it may have been divided into two, which would then be nearly square. Such subdivisions of long chambers are not uncommon. The side-walls, no doubt, consisted of large slabs. On the plan are two fallen stones (3), and another lies within the chamber. In Costello's view three or four appear to be represented close to the upright stone at the north end, but whether they are meant for really separate stones or some conformation of the natural rock is not certain.

It is so unusual to find an entrance in the side walls of a chamber, (nor is there any instance recorded as far as has been ascertained) that it will be safer to presume that the present instance is no exception. The entrance, therefore, as already suggested, must have been at the southern extremity. It is true that such a position for an entrance is very unusual, but it follows from the position of the chamber itself, which is no less unusual, as the great majority of such chambers lie either exactly or nearly east and west, the entrance being usually at the former. All that can be stated for certain in the present instance is that wherever the entrance was, it could not have been at the north end, as it would have been impossible to move that stone without bringing down the capstone and destroying the chamber.

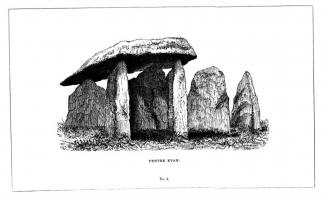

Cut No. 2 represents a back view of the cromlech, and is from an enlarged drawing of the illustration that accompanies Sir Gardner Wilkinson's account. This exhibits what has before not been noticed by any one except Sir Gardner, namely the two upright stones on the south end. He thinks they had no connexion with the cromlech, and that their use and purpose are unknown. In one sense, indeed, they were not connected with the cromlech, but were portions of an exterior chamber, distinct from, but adjoining, it. Their exact position will be better understood from the plan and drawing, and is such as to indicate that they are portions of a multangular chamber. There are other multangular chambers, as at Bryn Celli Ddu in Anglesea, and at Capel Garmon near Llanrwst. The cromlech at Presaddfed, near Treiorwerth in Anglesey, consists of a rectangular and hexagonal chamber. If a stone is placed in a position corresponding with the larger of these two stones, and abutting against the westernmost of the three stones at the south end of the chamber, the outline of a polygonal chamber is easily made out, and would be completed by the addition of four or five similar stones. One of the missing ones may be the one marked as fallen. This outer chamber would thus be a kind of vestibule to the rectangular chamber, and was also probably entered from the south side. It is true that we have examples of galleries leading to chambers which are not always in the same line, but make a considerable bend or angle, and there may have been something of the kind in this instance; but, on the whole, the supposition of an exterior polygonal chamber is the most natural and the most probable, as the position of the larger of the two stones is most awkwardly placed for a gallery. Excavations of the ground may possibly throw some light on the question. In the adjoining hedges and ditches and mostly near the cromlech are numerous large stones, which on the enclosing of the land seem to have been thrust where they would be most out of the way. Others may have been removed or destroyed, but there cannot be any doubt that if not all, at least the greater part, of those that remain have been once connected with the monument.

The mound of earth or stones that enveloped the whole structure, including the external chamber, must have been so large as to inspire doubts even in an authority like Sir Gardner Wilkinson, as to its having been enveloped. When Mr. Fergusson talks of the impossibility of there having been a chamber, and of its being covered up, he talks about what he knows nothing at all; for there is no difficulty in the matter so long as mounds do exist which to this day cover up much larger and more extensive groups of structures. Even in Wales exists a cairn or mound of stones long enough to contain at least six cromlechs like that of Pentre Evan, and which even in its semi-ruined state might almost be high enough. If any one doubts this, he can find his way to Carnedd Hengwm, near Cors y Gedol, and judge for himself.

The dimensions of Pentre Evan cromlech have been variously given. Those of Sir Gardner Wilkinson are as follows: greatest height from lower surface of capstone to ground in the centre is 7 ft. 7 ins., or 2 ins. short of a measurement made by Mr. F. Lloyd Phillips of Penty Park and myself. The length between the north and south supporters, 10 ft. The height of the two southern supporters is 7 ft. 9 ins., and of the northern one, 7 ft. The capstone is given 16 ft. 6 ins. by 9 ft. 4 ins. George Owen states, that it was 18 ft. long, independent of a piece 10 ft. long and 5 broad, which he says had been evidently broken off; but this could not have been the case. The fragment he saw may, however, have been a part of a side-wall thrown down. Mr. Lloyd Phillips' measurement of the extreme length was 17 ft. 3 ins. The chamber may be set down as 10 ft. long by about 6 ft. broad.

The situation is very fine, and commands a view of the sea, as is often the case with cromlechs. The only habitation near it is a small cottage; but an ancient paved way leads from the ancient house of Pentre Evan to the higher ground on which the cromlech stands, as if a population once existed where none does at present. But whatever the history of this ancient road is, there can be little doubt as to that of the cromlech, and that it was built and used as the burial-place of a person of distinction, and most probably served as such for his successors, perhaps, for many generations.

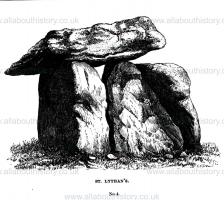

ST. LYTHAN S AND ST. NICHOLAS CROMLECHS.

These are two remarkable examples (particularly the one in the parish of St. Nicholas), neither of which seems to have been much noticed, although so well known, at least by report. One of them (that of St. Lythan's) was visited by the Association during the Cardiff Meeting in 1849; but all that is recorded of it in the Report of that Meeting is that it was "a fine old cromlech", and was sketched by some of the gentlemen present. The one at St. Nicholas does not appear to have been visited at all; but the weather was very unpropitious, and the hospitality of the late Mr. Bruce Pryce of a very genial character.

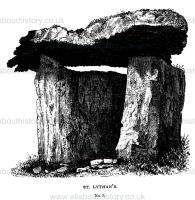

The St. Lythan's Cromlech [Map] is certainly a fine one, and, with the exception of the eastern end, presents a perfect chamber. Not a vestige remains of the tumulus, as might have been expected, as it was probably composed of earth. It stands east and west, and presents a chamber 7 ft. 10 ins. by 5 ft. The south wall is formed of a stone measuring 11 ft. 4 ins., while the north one is only 10 ft. 1 inch; so that it seems to have lost a stone which would have made the two side- walls of equal length, a necessary consideration if it were desirable that the eastern slab should fit as closely as possible, so as to leave few interstices to be filled up with small stones. It is generally thought that the three sides of a chamber were first erected, and the capstone placed thereon; then the interment took place, and the fourth side placed last, and the tumulus completed. That such was the practice there can be little question, if it is conceded that the proper course would be to complete the chamber as far as possible before the interment took place. To erect the four sides, then inter, and finally place in position the capstone, would be more inconvenient; and in the case of large capstones, risk to the remains interred would be incurred in case any accident happened in the moving of the capstone into place. As arrangements, moreover, for future interments were necessary, one side must be capable of being removed,which must, therefore, have not supported the capstone; so that it was far more convenient to build up only three sides on capstones, and complete the fourth after the interment. Hence it is that this part of a chamber is almost universally wanting, the other parts generally owing their preservation as contributing to support the capstone.

Cut No. 3 is from a drawing of Mrs. Traherne of Coed-riglan, who has kindly placed it at the disposal of the Society.

Cut No. 4 presents the western view, or back of the cromlech, and is copied from a stereoscope of the Eev. Walter Evans, by Arthur Gore, Esq., to whose ready pencil the Association has been on so many occasions indebted. The general view of this cromlech is exceedingly fine, presenting a grand, massive appearance which any engraving must fail to reproduce.

The St. Nicholas Cromlech [Map], though less picturesque, being nearly buried in earth, and in a thick wood, is one of great interest and importance. A photograph of it was kindly sent by Mr. Walter Evans; but was useless on account of the deep shadows. In fact, photographs of cromlechs are almost always useless, unless supplemented by drawings taken of the original from the same point of view. It was the same with a photograph of the St. Lythan's, and which by itself was perfectly unintelligible to one who did not know the details. In Lewis' Topographical Dictionary it is thus described: "It consists of large flat stones nearly 6 ft. in height, enclosing an area of 17 ft. in length by 13 in breadth, upon which rests a table 24 ft. long, and varying in breadth from 17 to 10 ft." This description is tolerably correct, except that the length of the chamber is 19 ft. 9 ins., and the breadth hardly 11; but as upon one side of the chamber all the stones have been removed, it is not easy to decide where the line should be drawn. The stone at the head of the chamber is 7 ft. 8 ins. broad, and had apparently a small one on one side. The proper breadth of the chamber is 10 ft. 6 ins. The opposite end was closed by stones 2 ft. 11. ins., and 5 ft. 8 ins.: in all, 8 ft. 7 ins. A stone is missing, probably 2 or 3 ft. broad, which would make this end correspond with the breadth of the opposite one. The other side is formed of one long stone 15 ft., leaving a gap of 3 ft. at each end to complete its length. The entrance was probably to the right of the present one, as either of the two stones can be moved which is not the case with that at the opposite end. The bearing is south-east. The original soil is still heaped on the top of the stones, but has been almost cleared off the face of the capstone, which has had the smaller part cracked or broken, but still remaining in its place. The greatest thickness is about but even this does not seem to have been equal to bear the weight of the tumulus, which has probably caused the crack, especially when the great length of the stone is considered. Larger capstones are in existence, but this is probably the largest or at least the longest in these islands. There are several vast rocks of the same character scattered about, brought thither by natural causes; and it is their presence which, no doubt, has led to the erecting of these two chambers in this locality. E. L. Barnwell.