Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that `abled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page.

Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

Abbot John Whethamstede’s Chronicle of the Abbey of St Albans

Abbot John Whethamstede's Register aka Chronicle of his second term at the Abbey of St Albans, 1451-1461, is a remarkable text that describes his first-hand experience of the beginning of the Wars of the Roses including the First and Second Battles of St Albans, 1455 and 1461, respectively, their cause, and their consequences, not least on the Abbey itself. His text also includes Loveday, Blore Heath, Northampton, the Act of Accord, Wakefield, and Towton, and ends with the Coronation of King Edward IV. In addition to the events of the Wars of the Roses, Abbot John, or his scribes who wrote the Chronicle, include details in the life of the Abbey such as charters, letters, land exchanges, visits by legates, and disputes, which provide a rich insight into the day-to-day life of the Abbey, and the challenges faced by its Abbot.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

Archaeologia Cambrensis 1999 Pages 207-213 is in Archaeologia Cambrensis 1999.

A fresh look at Ystum Cegid Isaf Megalithic Tomb [Map] (Caern.) By Frances Lynch.

The monument at Ystum Cegid Isaf in Llanystumdwy parish (SH 499 413) situated in the broken, rocky, marshy country north of Criccieth has not received a great deal of attention in recent megalithic studies. It has been much disturbed and is one of several sites which have been re-erected—always a source of uncertainty in analysis; moreover, if it is a Passage Grave, it is an awkward outlier, unrelated to its nearest neighbours. Consequently few people have been keen to discuss it at length. On its last appearance in Archaeologia Cambrensis it was described in rather condescending terms as 'not a specimen of the first importance, although of considerable size' (Anon, 1904, 148).

This twentieth-century neglect contrasts with the situation in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the monument was described and drawn several times (Farrington, 1769; Rhyl MS 1772; Pennant, 1783; Colt Hoare Views in Wales NLW edition; Pugh, 1816; Barwell, 1869; Owen, 1903 (quoting Williams, 1871)).

The first commentators were impressed by the monument in its much more complete form, although when first described most of the cairn must have alreacy been removed and the surviving chamber perhaps incorporated into a stone wall.

Farrington in his Snowdonia Druidica of 1769 provides a description [of Ystum Cegid aka Coetan Arthur Burial Mound [Map]] and a very clear diagram which shows the large thin capstone supported by six uprights, with cairn material on top of it, with two other overlapping capstones to the north; the first with one stone and the other with three stones visible beneath it. There is a hint that stones may have filled the chamber and the front of the passage. This drawing of a continuous tripartite structure is the crucial image and it is consistent with the present remains, despite subsequent interference (Fig. 1.1).

Farrington's record is corroborated by an MS account of 1772 published in Archaeologia Cambrensis for 1849. This speaks of 'a grand triple cromlech called Coetan Arthur', the largest 'table stone' being triangular, supported by 6 pillars; the second which rests upon it is a 'trapezium' standing on 3 pillars and the third roof stone, 'a flat quadrilateral shiver', stands upon 4 pillars. 'The ends of the middle covering stone rest upon the other two', exactly as shown in Farrington's sketch. The dimensions of the main capstone given in this text are about 25% too small, so the size of the other capstones have been increased by this amount in the reconstructed plan (Fig. 2.1).

Pennant speaks of 'three cromlechs joining each other' (1783, ii, 360) a phrase which has caused some confusion to later commentators, notably E.L. Barnwell (1869, 135) and Glyn Daniel (1950, 192) who interpret this as three independent chambers of some sort, rather than the three capstones of a single structure, which is what Farrington and the Rhyl 1772 MS describe.

Pugh in his Cambria Depicta of 1816 provides the next image, which shows the chamber only (Fig. 1.2). Presumably the two other capstones had been removed by then and their supporters were concealed by the field wall, although he does not show any walling abutting the chamber. One of the figures may be sitting on the remains of a passage stone; clearly he is not concerned with realistic scale. The chamber retains its six widely spaced supporters; it was being used as a cow-house and the gaps were filled by rubble (also not shown on the drawing). It was assumed that this walling was modem.

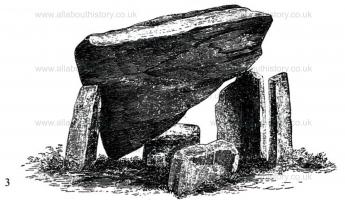

The next record is that of Barnwell (1869, 135-7) who provides a drawing which shows the capstone dislodged and tipped to the east (Fig. 1.3). Two stones are lying beneath it and three remain standing. The sixth one has entirely disappeared by this time. An MS account by J.G. Williams written in 1871 but not published until 1903 (Owen, 1903, 260) records that the capstone was disturbed in 1863 by the tenant wanting the supporter as a lintel, but the stone was trapped by the fzll of the capstone and he was unable to get it away. Barnwell mentions stones around the chamber which he thinks are the remains of the original cairn but he does not mention the wall nor does he recognise the surviving supporters of the other two capstones. He assumes that two cromlechs were entirely removed some fifty years previously and perhaps did not look for them.

By the time J.E. Griffith photographed the site in 1900 the monument looked exactly as it does today (Griffith, 1900; also used in Anon, 1904). The eastern supporter had been re-erected and so had the western one which is shown fallen in 1869. This stone seems to have been broken in the process but the eastern one was undamaged since the capstone is as level as it was in Farrington's sketch. The monument is clearly incorporated into a field wall but the chamber itself is free of debris. There is no record of when this reconstruction was effected, or by whom. Presumably it was done by Lord Harlech (Griffith, 1900).

All About History Books

The History of William Marshal was commissioned by his son shortly after William’s death in 1219 to celebrate the Marshal’s remarkable life; it is an authentic, contemporary voice. The manuscript was discovered in 1861 by French historian Paul Meyer. Meyer published the manuscript in its original Anglo-French in 1891 in two books. This book is a line by line translation of the first of Meyer’s books; lines 1-10152. Book 1 of the History begins in 1139 and ends in 1194. It describes the events of the Anarchy, the role of William’s father John, John’s marriages, William’s childhood, his role as a hostage at the siege of Newbury, his injury and imprisonment in Poitou where he met Eleanor of Aquitaine and his life as a knight errant. It continues with the accusation against him of an improper relationship with Margaret, wife of Henry the Young King, his exile, and return, the death of Henry the Young King, the rebellion of Richard, the future King Richard I, war with France, the death of King Henry II, and the capture of King Richard, and the rebellion of John, the future King John. It ends with the release of King Richard and the death of John Marshal.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

The present remains were planned by the Royal Commission in the 1950s and show a large rhomboid chamber covered by a thin capstone whose shape determines that of the chamber beneath. It stands on the line of a modern field wall which incorporates four orthostats which can plausibly be interpreted as the remains of a narrow passage running north from the chamber. The curving line of the wall suggests that the passage was markedly crooked when more stones survived and the wall was built along it. Alongside the western side of the wall is a spread of stony material overlaid by what is clearly a modern dump of boulders from the field. The lower, grass-covered stones must be the remains of a cairn but its elongated shape has clearly been influenced by the presence of the wall. Nearly all the stones have been cleared from the eastern side.

All these features are consistent with the earlier descriptions discussed above and, with the re- erection of the easternmost stone, the present structure, though lacking the passage capstones, is as close to the original monument as we can get.

The two significant elements are the large polygonal chamber with an angular floor plan and the passage running north from it for some Sm. These elements have led to its identification as a Passage Grave which should be set within a large circular mound. the present length of the mound suggesting a diameter of about 20-23m. This interpretation was firmly made by W.F. Grimes in 1936 (Grimes, 1936, 128) who used the Farrington drawing as his main evidence, and has been followed by all subsequent writers, including the present one (Lynch, 1969, 139, 301) with little further comment. The presence of Bryn Celli Ddu as a single example of a similar tomb in Anglesey enabled one to ignore the rather unusual isolation of the tomb from other Passage Graves and also its uncharacteristic low-lying, almost hidden, situation (despite being set on a local eminence).

However, while the evidence of the present remains and of Farrington's drawing makes it undeniable that the monument was designed as a polygonal chamber approached by a narrow passage, it is possible to argue that it belongs to a different cultural group altogether from the classic Passage Graves of the Carreg Samson or Bryn Celli Ddu type; that group being the Cotswold Severn group in its rather eccentric south-east Welsh form.

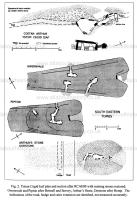

The characteristics of Ystum Cegid Isaf are a large (4.3m x 3m; 1.75m high) chamber of angular shape which reflects that of the capstone above, widely spaced orthostats, constricted access (0.5m) between the passage and chamber, a curving or crooked passage of uniform height and, as remarked by Barnwell, an unusually thin capstone, in a region where other tombs use especially massive stones (for example nearby Cefn Isaf and Tan y Muriau (Lynch, 1969)). These features can best be matched among the cairns of Breconshire and Herefordshire, especially Gwernvale and Arthur's Stone, Dorstone (Fig. 2).

At Gwernvale Chamber measures 3m by 2m and has an asymmetric pointed oval plan which was probably dictated by the capstone removed in 1804. The orthostats on the north side are widely spaced and the intervals are filled with neat dry-stone walling. Dry walling at Ystum Cegid Isaf was assumed to be modern, but may not have been. The height of the Gwernvale chamber was probably about 1.75m, roughly the same as that of Ystum Cegid Isaf. Access to the passage is narrow and deliberately constricted. The passage is gently curved on one side and, at 4.5m, is approximately the same length as that at Ystum Cegid Isaf; it is extended for a further metre by dry walling (Britnell and Savory, 1984, 66). At Gwernvale the passage was rather lower than the chamber and its height may have decreased towards the edge of the caim, but the outer orthostats are too damaged for certainty.

Arthur's Stone, Dorstone [Map], has not been excavated and the total plan is unknown, but it contains a very large polygonal chamber covered by a single thin cover-slab of the same shape and approached by an angled passageway (Hemp, 1935). The chamber measures 4.5m x 2m and has a narrow entrance like that at Ystum Cegid Isaf. The passage is sharply angled and reminiscent of that at Pipton in Breconshire (Savory, 1956 and Fig. 2); its total length is unknown because the edge of the cairn is undefined.

The overall plans of the cairns of the Black Mountain group are very idiosyncratic so itis difficult to predict the arrangement of chambers at any particular monument (Corcoran, 1969: Britnell and Savory, 1984; RCAHM(W), 1997). However it can be said that all are in long cairns (the cairn at Arthur's Stone can be easily recognised extending into the field to the north and this has been sketched in on Fig. 2); that they have narrow forecourts leading to a false portal and that they contain a multiplicity of chambers. These chambers normally open from the sides of the cairn and include relatively small rectangular structures but also, in most cairns, a 'main chamber' which is significantly larger and/or more complex in design than the others.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke

Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

At Ystum Cegid Isaf very little of the cairn survives and its shape is clearly related to the presence of the wall built over it. However the line of that wall itself may have been dictated by the presence of an elongated cairn. Its present length is about 24m; comparison with tombs in the south would suggest that it could have been between 30m and 50m originally. The manuscript of 1772 ( Rhyl MS 1849) speaks of a number of other large stones in the general vicinity. It is difficult to judge whether they could have been part of the same monument, but it is worth mentioning 'a directing stone' 'in the way to it' and 'in the field adjoining it, a tall pillar, another lying on the ground very near it'. It is just possible that one or other of these might have been part of a false portal. It is difficult to visualise the three pointed 'columns' standing in a stone wall 'not far from' the grand triple cromlech because only length and breadth measurements, not height, are given. They are possibly of a size to have been part of rectangular chambers like those at Ty Isaf (Grimes, 1939), but they may be quite separate and irrelevant.

As an isolated Passage Grave Ystum Cegid Isaf was somewhat difficult to explain within a historical context. As a representative of the Cotswold Severn group it fits much more easily into a pattern. Capel Garmon above Llanrwst has for long been recognised as part of the group (Hemp, 1927) and Carnedd Hengwm North in Ardudwy is clearly another, and less certainly, Tan y Coed near Bala (Bowen and Gresham, 1967, 15, 31). It can also be argued that Carnedd Hengwm South and Tan y Muriau on Mynydd Rhiw are earlier Portal Dolmens which have been modified and extended under the influence of these new design ideas (Lynch, 1976). To claim, therefore, that Ystum Cegid Isaf, mid way between Ardudwy and the tip of Lleyn, is also a member of this group gives it a more comfortable context within the middle Neolithic of the region.

Bibliography

Anon 1904 'Report on Portmadoc Meeting', Arch. Camb. 1904, 146-51.

Barnwell, E.L. 1869 'Cromlechs in North Wales', Arch. Camb. 1869, 118-47.

Bowen, E.G. 1967 History of Merioneth vol. 1, Dolgellau. and Gresham, C.A.

Britnell, W.J. 1984 Gwernvale and Penywyrlod: Two Neolithic Long Cairns in the and Savory, H.N. Black Mountains of Brecknock. Cambrian Archaeological Monographs No. 2, Cardiff.

Corcoran, 1969 'The Cotswold-Severn Group: 1 Distribution, Morphology JFX.W.P. and Artifacts' in Powell et al, 13-72.

Daniel, G.E. 1950 The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of England and Wales, Cambridge.

Farrington, R. 1769 Snowdonia Druidica (Nat. Library of Wales MS 1118).

Griffith, J. E. 1900 Portfolio of photographs of the Cromlechs of Anglesey and Caernarvonshire reproduced in collotype, Nixon and Jarvis, Bangor.

Grimes, W.F. 1936 'The Megalithic Monuments of Wales', Proc. Prehist. Soc. 2, 106-39.

Grimes, WF. 1939 'The Excavation of Ty Isaf Long Cairn, Brecknockshire', Proc. Prehist. Soc. 5, 119-42.

Hemp, W.J. 1927 'The Capel Garmon Chambered Long Cairn', Arch. Camb. 1927, 1-44.

Hemp, W.J. 1935 'Arthur's Stone, Dorstone, Herefordshire', Arch. Camb. XC, 1935, 288-92.

Lynch, F.M. 1969 'The Megalithic Tombs of North Wales' in Powell ef al. 107-48.

Lynch, F.M. 1976 'Towards a Chronology of Megalithic Tombs in Wales' in G.C.Boon and J.M. Lewis (eds) Welsh Antiquity: Essays presented to HN. Savory, Cardiff, National Museum of Wales, 63-79.

Owen, E. 1903 'Ancient British Camps etc in Lleyn, Co. Caernarvon' transcribed by E. Owen from MS of 1871 by J.G.Williams of Pwllheli, Arch. Camb. 1903, 251-62.

Pennant, T. 1783 Tours in Wales (J. Rhys ed. Caernarvon, 1883).

Powell, T.G.E. 1969 Megalithic Enquiries in the West of Britain, Liverpool etal. University Press.

Pugh, E. 1816 Cambria Depicta, London.

RCAHM(W) 1997 Brecknock: Later Prehistoric Monuments and Unenclosed Settlements to 1000 AD, HMSO.

Rhyl MS 1772 "Celtic Antiquities II' Arch. Camb., 1849, 1-6.

Savory, H.N. 1956 'The Excavation of the Pipton Long Cairn', Arch. Camb.CV, 1956, 7-48.