Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Abbot Ralph of Coggeshall describes the reigns of Kings Henry II, Richard I, John and Henry III, providing a wealth of information about their lives and the events of the time. Ralph's work is detailed, comprehensive and objective. We have augmented Ralph's text with extracts from other contemporary chroniclers to enrich the reader's experience. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Beauties of the Boyne is in Prehistory.

We are now in a position to inquire after the site of Brugh na Boinne, the royal cemetery of "the Fort of the Boyne." About two miles below Slane the river becomes fordable, and several islands break the stream. Here, upon the left, or southwestern bank of the river, is the place called Rossnaree, the ancient Ros-na-Eigh, or the Wood of the Kings, and upon the opposite swelling bank of the river occur a series of raised mounds, raths, forts, caves, circles, and pillar-stones, bearing all the evidence of ancient Pagan sepulchral monuments, which, there can now be little doubt, was the Irish Memphis, or city of tombs, already so frequently alluded to. The following reference from the History of the Cemeteries, already referred to, will, we think, set the question at rest, and fix the site of Brugh-na-Boinne here, and not, as has been conjectured, at Stackallan. We already mentioned, in describing Clady, that King Cormac Mac Art died at the house of Cletty. His burial is thus detailed: "And he (Cormac), told his people not to bury him at Brugh (because it was a cemetery of idolaters); for he did not worship the same God as any of those interred at Brugh; but to bury him at Ros-na-Eigh, with his face to the east. He afterwards died, and his servants of trust held a council, and came to the resolution of burying him at Brugh, the place where the kings of Tara, his predecessors, were buried. The body of the king was afterwards thrice raised to be carried to Brugh, but the Boyne swelled up thrice, so as that they could not come; so that they observed that it was violating the judgment of a prince to break through this testament of the king; and they afterwards dug his grave at Eos-na-Eigh, as he himself had ordered." And again, "The nobles of the Tuatha De Danaan were used to bury at Brugh."

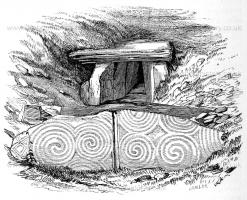

When we first visited New Grange [Newgrange Passage Tomb [Map]], some twelve years ago, the entrance was greatly obscured by brambles, and a heap of loose stones which had ravelled out from the adjoining mound. This entrance, which is nearly square, and formed by large flags, the continuation of the stone passage already alluded to, is now at a considerable distance from the original outer circle of the mound, and consequently the passage is at present much shorter than it was originally, if, indeed, it ever extended so far as the outer circle. A few years ago, a gentleman, then residing in the neighbourhood, cleared away the stones and rubbish which obscured the mouth of the cave, and brought to light a very remarkably carved stone, which now slopes outwards from the entrance. This we thought at the time was quite a discovery, inasmuch as none of the modern writers had noticed it. The Welsh antiquary, however, thus describes it: — "The entry into this cave is at bottom, and before it we found a great flat stone, like a large tomb-stone, placed edgeways, having on the outside certain barbarous carvings, like snakes encircled, but without heads."

This stone, so beautifully carved in spirals and volutes, as shown in the graphic illustration upon the opposite page, is slighty convex, from above downwards; it measures ten feet in length, and is about eighteen inches thick. What its original use was, — where its original position in this mound, — whether its carvings exhibit the same handiwork and design as those sculptured stones in the interior, and whether this beautiful slab did not belong to some other building of anterior date, — are questions worthy of consideration, but which we have not space to discuss.

During the excavations some very interesting relics and antiquities were discovered. Among the stones which form the great heap, or cairn, were found a number of globular stone shot, about the size of grape-shot, probably sling-stones, and also fragments of human heads; within the chamber, mixed with the clay and dust which had accumulated, were found a quantity of bones, consisting of heaps, as well as scattered fragments of burned bones, many of which proved to be human; also several un burned bones of horses, pigs, deer, and birds, with portions of the heads of the shorthorned variety of the ox, similar to those found at Dunshaughlin, and the head of a fox. Glass and amber beads, of unique shapes, portions of jet bracelets, a curious stone button or fibula, bone bodkins, copper pins, and iron knives and rings, the two latter similar to those found at Dunshaughlin, were also picked up. Some years ago a gentleman who then resided in the neighbourhood cleared out a portion of the passage, and found a few iron antiquities, some bones of mammals, and a small stone urn, which he lately presented to the Academy. Much might here be written upon the remains of the Fauna known to the ancient Irish, did our space permit; we can, however, merely specify some of the bones, and mention some of the articles which were discovered. In the beginning of the last century, a stone urn, somewhat similar in shape to "the upper part of a man's skull," was found in a kistvaen at Knowth; this, we believe, is now in the collection of the Academy; it is figured by Molyneux.