Text this colour is a link for Members only. Support us by becoming a Member for only £3 a month by joining our 'Buy Me A Coffee page'; Membership gives you access to all content and removes ads.

Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Handbook of Irish Antiquities by Wakeman Chapter 1 is in Handbook of Irish Antiquities by Wakeman.

Chapter 1. Stone Monuments

It is now admitted by all competent authorities that the works scattered throughout Ireland, varying from the rude structures known as cromlechs and the gigantic chambered cairns, like those of Newgrange and Dowth, down to the simplest cist, alike varieties of the cromlech idea, are graves of a primitive people. But we may go a step further than this. It is perfectly evident that the people who erected the cromlechs and tumuli were far more solicitous about the abodes of the dead than they were regarding their own dwellings, built as these were of wood and wattles, covered with turf and earth, and subject to ready decay. 'On the other hand,' as Dr. Munro well says, 'the tomb was constructed of the most durable materials, and placed on an eminence, so as to be seen from afar, and to be a lasting memorial among succeeding generations.25

Note 25. Prehistoric Scotland, p. 279.

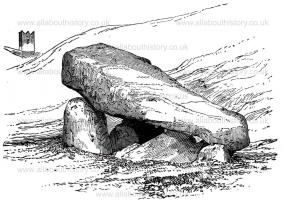

Towards the close of the Stone Age the custom of burning the bodies of the dead was practised by the inhabitants of the British Isles. The dead were also disposed of by ordinary burial, by placing the body in either a horizontal, sitting, or perpendicular position. Both methods were practised throughout the whole succeeding archæological period, or Bronze Age, as numerous remains testify. When cremated, the calcined remains were placed in an urn, and then deposited, often with a small food-vessel, within an artificial chamber. This is called a Cist, or Kistvaen, and is usually a small rectangular chamber made of flags or rude stones. Over these chambers it was often customary to raise a cairn of stones or earthen mound. The cist has, however, been frequently found in open fields and other unexpected places. Cinerary urns, too, have been found within an area of stone circles, in tumuli not many feet from the surface, and in mounds that in their centre contained other, and probably more ancient, burial deposits.

In case of interment the grave was sometimes formed of flags, often of considerable size, placed edgeways, and enclosing a space, covered with stones, barely sufficient to contain the body, and over which a cairn or mound was raised. The body was also deposited in a chamber formed of large rude stones, often found standing free; but sometimes the chamber was covered by a mound or cairn, and was accessible by a passage from without. To the uncovered remains of these burial structures the name Cromlech is generally applied. The cairn or mound was often surrounded by a circle of stones, and50 traces of this still exist in some of the sepulchral monuments. Sometimes the space in which the remains of several bodies have been found is barely sufficient for one body, and it is supposed that they were broken before interment. Cremated remains are often found with the remains of an interred body; and this may have been the result of human sacrifices offered to the manes of the dead.

An interesting account of burial in an upright position is referred to in the Book of Armagh, where King Laoghaire is represented as telling St. Patrick that his father Niall used to exhort him never to believe in Christianity, but to retain the ancient religion of his ancestors, and to be interred in the Hill of Tara, like a man standing up in battle, with his face turned to the south, as if bidding defiance to the men of Leinster.

'Cremations and bodily interments,' says Colonel Wood-Martin, 'have been found intermixed in a manner to lead to the belief that both forms of burial prevailed contemporaneously. Urns to contain the ashes of the dead were, possibly, used as a special mark of honour; also, perhaps, to facilitate the conveyance of the human remains from a distance to the chosen place of interment. In a country wherein were thick woods and long stretches of bog to be traversed, the passage of funeral processions must have been attended with delays and difficulties.'

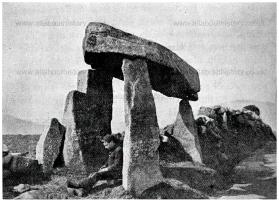

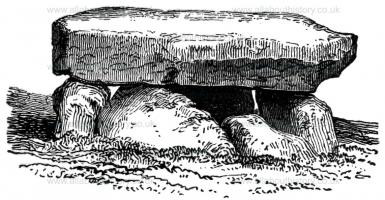

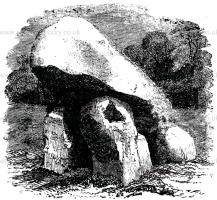

The ordinary Cromlech, when perfect, or nearly so, consists of three or more stones, unhewn, and generally so arranged as to form a small enclosure. Over these a large and usually thick stone is placed, the whole forming51 a kind of vault or rude chamber. It is generally rude in appearance, the stones often consisting of mere amorphous blocks. In Clare, where the limestone is found more or less in a laminated form, the cromlech becomes more symmetrical, and is often very perfect in shape.

The cromlech is usually styled 'Dolmen' by English and Continental writers. Our peasantry, however, as a rule, call them 'Giants' Graves,' or not unfrequently, when retailing a tradition and speaking in Irish, 'Leaba Diarmida agus Graine,' or the Beds of Dermot and Graine, from two historical personages who, according to an old legend, eloped together, and flying through the country for a year and a day, erected these 'beds' wherever they rested for a night. Graine, or Grace, was the betrothed wife of Fin Mac Coul, and daughter of King Cormac Mac Art, who lived about the middle of the third century A.D.; her lover was Diarmid O'Duibhne, of whom several stories are still current. According to this legend there should be just 366 cromlechs, or 'beds,' in Ireland. But mythical as the story is, it is nevertheless of some interest, as it connects the monuments with pre-Christian events. In parts of the north and west of the country they are sometimes styled 'griddles.'

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

The true Chamber Monument is an extended form of the cromlech, and differs from it in that the roof is formed by a succession of overlapping slabs resting on the stones forming the walls, and gradually rising from the lower end. The top cap-stone, while resting on the uprights, not only closes the chamber, but by its weight52 keeps in position the overlapping stones which help to support it.

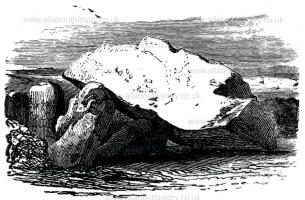

In some cases the covering stone of the cromlech seems to have slipped from its original position, and will be found with one end or side resting upon the ground. Du Noyer was of opinion, shared by the late Mr. Borlase, that this was originally the case in some examples, the builders having failed in their efforts to raise the ponderous table or covering stone, or to procure suitable supports. The position of the upper stone, or roof, is usually sloping; but its degree of inclination does not seem to have been regulated by any intention or design. This general disposition of the 'table' has been largely seized upon by advocates of the 'Druids' Altar' theory, as a proof of the soundness of their opinion that these monuments were erected by the Druids for the purpose of human sacrifice. Some, indeed, have gone so far as to discover in the hollows worn by the rains and storms of centuries on the upper surface of these stones, channels artificially excavated, for the purpose of facilitating the passage of a victim's blood earthwards!

The question whether the cromlech was originally covered by a cairn or mound has been the subject of much discussion, but its full consideration is outside the limits of this work. The great majority of existing cromlechs in Ireland are, now at least, of the free-standing order. Of these some, from the nature of their position and structure, could never have been the centres of tumuli. Others, no doubt, were covered; but, in the case of most, time has so altered their condition that it is now difficult to determine how they really stood in53 their original and finished state.26 A little consideration will show that, as the cromlech and covered chamber belong to the same general class of sepulchral monuments, it was intended by the original builders that access should be had to them from without. Mr. Borlase, agreeing with Fergusson, is 'inclined to regard the dolmens as no mere tombs intended to be closed for ever, but as sacred shrines in which the spirits of the dead were worshipped, and which were constructed with a view of being accessible to devotees.'27 The remains deposited within had to be protected from the severity of the weather and the intrusion of wild animals. In the case of the uncovered cromlech all intervening spaces would be closed up with smaller stones and earth, and the walls banked up to the edge of the cap-stone. Mr. Borlase advances the theory that the cromlech, hitherto technically so-called, is the more megalithic portion of the giant's grave, and 'that both types, despite the difference in their appearance in the condition in which we now find them, belong to one and the same class of dolmen, originally of elongated form.'28 He supports this by pointing out that the 'giant's grave' is a long, wedge-shaped structure, rising gradually from a lower to a higher end, the latter having the heavier supports and larger covering stone. These would be the more difficult to destroy, for, in the long lapse of time, as stones were required for building or other purposes, the smaller and lighter would be carried away. How far this may be the case we cannot here consider; but some cromlechs, such as those raised of great boulder rocks, could never have been of the extended order of structure.

Note 26. Mr. G. A. Lebour, in Nature, May 9th, 1872, speaking of the character of the principal dolmens and cist-bearing mounds of Finisterre, says that 'in most cases in that department the dolmens occupy situations in every respect similar to those in which the tumuli are found, so that meteorological, and indeed every other but human, agencies must have affected both in the same manner and degree. Notwithstanding this, the dolmens are invariably bare, and the cists are as constantly covered; there are no signs of even incipient degradation and denudation in the latter, and none of former covering in the first.'

Note 27. Dolmens of Ireland, vol. i., p. 8.

Note 28. Ibid., p. 430.

The number of these sepulchral remains scattered throughout the country is very great. Mr. Borlase enumerates them as follows: dolmens, certain, 780; chambered tumuli, 50; uncertain, 68—total, 898. Of these dolmens, Connaught has 248; Munster, 234; Ulster, 227; and Leinster, 71. The counties richest in these are—Sligo, 163; Clare, 94; Donegal, 82; and Cork, 71. The area of geographical distribution of these megalithic monuments is very wide. It extends from western Asia—Syria, Palestine, and Turkey—over north Africa, through south-east Europe, France, Spain, Portugal, over north Germany, and northern Europe. In France they reached a high degree of perfection. England and Wales furnish many examples similar to the Irish cromlechs; but they are rarely, if ever, found in Scotland.

The question naturally suggests itself, How were a primitive people, with such rude mechanical means as they possessed, able to raise those huge stones into the positions in which they are now found? Several theories have been advanced, which may be briefly stated. It has been suggested that the great covering stones of the cromlech having been found in situ, they were undermined, and a chamber formed beneath by the removal of the earth. As the work progressed uprights were by degrees placed in position, of sufficient weight and strength to support the great covering stone. Instances are found in Ireland to which this theory might, perhaps, apply; but the method could not have been adopted in such cases as that of the Ballymascanlan cromlech, where the cap-stone rests on clear supports 8 or 9 feet high. The plan suggested by the King of Denmark has been accepted by many, and it may have been adopted in some cases. In this, the supporting stones having been placed in position, an inclined plane or bank of earth would be raised, sloping from the level of the uprights to the ground. Up this the roofing stone would be worked, over blocks of timber placed side by side, by means of levers, wedges, and haulage. The absence of all traces of such banks in existing cromlechs, and other considerations, have been urged against this method of raising these structures. On the ground that all cromlechs were originally of the 'giant's grave' order, Mr. Borlase urges the theory that the cap-stones were raised one by one, the largest first, until it fell into its place upon the highest uprights. He considers that the disarrangement in the lines of the side stones, and the presence occasionally of buttresses, support this view. By using beams of timber and rollers it was possible, with great and united human strength, to lever very heavy rocks, bit by bit, into position.

Given sufficient men, great masses of stone may be moved over long distances and raised into position, even with the rudest means. There is no evidence whatever to show that the ancient Egyptians possessed any machinery to economise human labour in moving great monoliths. They were, it must be remembered, especially favoured in the Nile as a waterway, and the quarries, as a rule, were near its banks. In their pictorial records, so graphic in illustrating every art and craft, there is no reproduction of any machine or engineering expedient, except those of the very simplest kind; but the records do show that they employed large bodies of men in this kind of work, who were specially trained to haul with military precision. The earliest record of such work is that of an official of the 6th Dynasty (3350 B.C.), who brought a monolith to Memphis, which required the services of 3000 men. A record on the tomb of Tehuti-hetap, an official of the 12th Dynasty (2622–2578 B.C.), shows a statue on a sledge, drawn by 176 men, divided into four parties of 22 pairs, each party to a single hawser. A superintendent stands on the knees of the statue, giving, as the inscription states, 'the time-beat to the soldiers,' by clapping his hands. The two obelisks, each 97½ feet high, and 300 tons in weight, erected by Queen Hatshepsut (1503–1481 B.C.), were cut in the quarries of Assuan, and transported to Karnak in seven months. A still more remarkable instance of transporting great masses of stone was that of the fallen statue of Rameses II., which must originally have been 60 feet high, and weighed 800 tons. But this work was eclipsed by the same monarch in the statue erected at Tanis in the north-east Delta, which must have stood 92 feet in57 height, and weighed 900 tons, at least. It was brought from the quarries of Assuan, 600 miles distant. With such examples as these, accomplished with simple means, there is nothing surprising in the erection of the rude megalithic monuments by the primitive inhabitants of these islands.

We shall now refer more specifically to some interesting examples of the numerous remains of the rude covered and uncovered chambers found in Ireland, as distinguished from the great tumuli presently to be described.

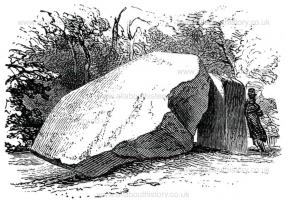

Kernanstown Cromlech, Carlow [Map]. Kernanstown Cromlech is about two miles north-east of Carlow, and is the largest in Ireland. This magnificent granite block is securely supported on three uprights at the east side, standing at a height of 6 feet. At the west end this cap is raised 2 feet. The block is 23½ feet long, 18¾ feet broad, 4½ feet thick, and measures 65 feet round. This is estimated to weigh 100 tons. It makes an angle of 35° with the horizon.

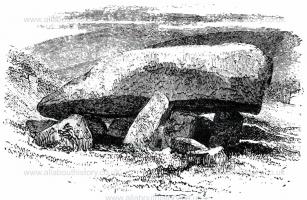

Labbacallee Cromlech [Map]. This, according to Mr. Borlase, 'the most noted dolmen of extended form in Ireland' lies about one and a half miles south-east of Glanworth on the old road to Fermoy. It consists of a double range of stones, the internal lines forming the supports of the covering stones. The largest of the cap-stones measures 15½ feet by 9 feet, the second being partially buried in earth. The entire measurement is estimated by Mr. Borlase to have been not less than 42 feet. The line of direction is east and west; the width of the inner chamber is 6 feet, and it is now 5 feet high, and sinks towards the lower end.29

Note 29. Dolmens of Ireland, vol. i., p. 8.

Monasterboice Cromlech. This fine monument lies about three-quarters of a mile to the north-east of the old graveyard of Monasterboice, and is known as 'Calliagh Dirra's House.' It is called by the peasantry the 'House or Tomb of Calliagh Vera, or Birra,' a mythic witch, whose name is associated with several wild legends referring to the mysterious cairns and other antiquities remaining upon the hills of Loughcrew, near Oldcastle. The work has been considered by some to be of the free-standing order; but Du Noyer says it must have been covered by a tumulus: it is roughly oblong in form, extending exactly east and west, showing the wedge-shaped plan, and measuring, internally, 12 feet 6 inches in length, by 4 feet at one end, and 359 feet at the other, in breadth. The north and south walls consist each of five large flagstones; four flagstones form the covering, and each end is closed by a slab. The stones forming the walls stand on edge, and some of these have supplemental stones and buttresses.

The Greenmount Chamber is about five miles further to the north, near Castlebellingham. Here, in 1870, General Lefroy opened an earthen mound, which was found to contain a chamber, the measurements of which were 21½ feet by 3 feet 4 inches, the height being 5 feet. The roof was formed of eight large flagstones. From the foundation to the top of the mound was 23 feet. Ashes, burnt bones, charcoal, and teeth of hogs and cattle were found. A bronze celt and plate, with runic character on one side, and elaborate interlaced pattern on the other, were found in the tumulus.

Cromlech of the Four Maols. This monument is on a hill close to the town of Ballina; the covering stone measures 9 feet by 7 feet, and is supported by three uprights. It is considered of much interest from an incident in early Irish history, mentioned in more than one Irish MS. It relates to the murder of Bishop Celleach, of Kilmore-Moy, son of Eoghan Bel, King of Connaught, and great-grandson of Dathi. Eoghan Bel was killed in battle at Sligo in 537, and in dying commanded the Hy Fiachrach to elect Celleach in his stead. Through the hatred of King Guaire, Celleach was murdered by the four Maols,30 his foster-brothers or60 pupils. The brother of the bishop captured the assassins, and carried them to the banks of the Moy, where they were executed upon a hill hence known as Ardnaree, or the 'Hill of Executions.' The bodies were carried across the river, and buried on a hill on the right bank.

Note 30. Maol may be interpreted 'servant of.'

But we cannot say for certain that the cromlech now standing there was erected to their memory. It is probable they were excommunicated and pronounced unworthy of Christian association, here and hereafter. As the bodies had to be disposed of, it is possible that as a further mark of ignominy in this case, they were thrust into a pagan sepulchre which had stood on the Hill of Executions for ages past; though, as Colonel Wood-Martin points out in dealing with the story, 'it would also appear as if the native Irish, long after the introduction of Christianity, sometimes continued to bury in ancient cemeteries.'31

Note 31. Some doubt has been thrown on the story as told in the 'Annals': see Journal Roy. Soc. of Antiq. Ir., 1897, p. 430.

Black Lion Chambers. About two miles and a-half from the village of Black Lion, in County Cavan, but on the borders of Fermanagh, may be seen two fine 'giants' graves,' the larger of which, measuring 47 feet in length by about 10 in breadth, remains in a complete state of preservation. Five flagstones, some of considerable thickness, closely cover this enormous work. It was, and partially still is, enclosed by an oval line of standing stones, some of which have fallen, while others, in number and position sufficient to convey an idea of61 the original plan, remain in situ. At one end occurs a small but apparently undisturbed stone circle. At a little distance stand a cromlech, the covering stone of which measures fifteen feet five inches in length by fifteen in breadth; also another cromlech, besides a considerable number of dallans or pillar-stones. In the immediate vicinity occurs a fine chambered cairn, which, but for the work of rabbit-hunting boys many years ago, might now stand complete. The chamber, or cist, was found to contain a fine cinerary urn. The question suggests itself, Why should this cist-bearing cairn remain almost perfect, while the neighbouring megaliths, if they were ever mound-enclosed, are found cleanly and completely bare? Again, at the Barr of Fintona, we find two important cairns remaining almost completely preserved; while close at hand is a 'giant's grave,' which, if ever covered, is now practically denuded.

Legananny Cromlech [Map]. This cromlech is in the townland of Legananny, on the southern slope of Cratlieve mountain, in Co. Down, about six miles north-west of Castlewellan. The cap is a coffin-shaped granite block, 11 feet 4 inches long, 4 feet 9 inches wide at the south-east end, and 3 feet at the foot or north-west end. It rests upon three upright pillars, the two at the south-west measuring 7 feet and 6 feet 2 inches respectively, the third block at the foot being 4 feet 5 inches high. An urn was found in the chamber beneath. It has no sign of ever having been covered; and Fergusson has instanced it as an example of the free-standing62 cromlech in combating the theory that all cromlechs were originally covered by cairns or mounds.

Ballymascanlan Cromlech [Map]. This fine cromlech is about 4 miles north-east of Dundalk, and is known as the 'Proleek Stone,' and the 'Giant's Load.' There is nothing to indicate that it was ever a chambered tumulus. The cap-stone is an erratic block of basalt, measuring 15 feet by 13 feet, and about 6 feet thick, and is variously estimated at 30 to 60 tons in weight.32 It is supported by three upright stones of slender63 shape, and the total height is about 12 feet. Adjoining is another cromlech of the extended form, and generally known as 'Giants' Graves.'

Note 32. The Rev. Maxwell Close makes the dimensions 12¼ feet by 9¼ feet, and 5¾ feet thick.

Phœnix Park Cists. The neighbourhood of Dublin furnishes many examples of these rude stone monuments of a prehistoric age. The ancient sepulchre situated in the Phœnix Park, Dublin, a little to the west of the Hibernian Military School, was discovered in the year 1838 by some workmen employed, under the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, in the removal of a tumulus which measured in circumference 120 feet, and in height 15 feet.64 During the progress of the work, four stone cists, or kistvaens, were exposed, each enclosing an urn of baked clay, within which were calcined bones and ashes, &c. One of these urns, which is now, with the skulls, shells, and other remains, in the Royal Irish Academy collection, arranged in a case in the National Museum, was fortunately saved in a nearly perfect state. The tomb at present consists of seven stones set in the ground, in the form of an irregular oval, three of which support a covering stone, which measures in length 6 feet 6 inches; in breadth, at the broadest part, 3 feet 6 inches; and in thickness between 14 and 16 inches. The spaces between the stones which formed the enclosure were filled with others of smaller size, which, since the discovery, have fallen out or been removed. The following is an extract from the report of the Academy: 'In the recess they enclosed, two perfect male human skeletons were found, and also the tops of the femora of another, and a single bone of an animal supposed to be that of a dog. The heads of the skeletons rested to the north; and as the enclosure is not of sufficient extent to have permitted the bodies to65 lie at full length, they must have been bent at the vertebræ, or at the lower joints. In both skulls the teeth are nearly perfect, but the molars were more worn in one than in the other. Immediately under each skull was found collected together a considerable quantity of small shells common on our coasts, and known to conchologists by the name of Nerita littoralis. On examination these shells were found to have been rubbed down on the valve with a stone to make a second hole, for the purpose, as it appeared evident, of their being strung to form necklaces; and a vegetable fibre, serving this purpose, was also discovered, a portion of which was through the shells. A small fibula of bone, and a knife, or arrow-head, of flint, were also found.'

Visitors to the Phœnix Park will find in the grounds of the Royal Zoological Gardens a cist, or diminutive cromlech, in many respects similar to that just noticed, which was discovered some years ago in a sandpit immediately adjoining the neighbouring village of Chapelizod. This monument, though not occupying its ancient position, and, notably, a restoration, should be seen by students of Irish antiquities, the stones of which it is composed having been carefully replaced in their original order. It is on record that within this tomb a human skeleton was found, but no mention of anything else it may have contained has been preserved.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

A much more important example of a removed Cist is now to be seen in the National Museum, Dublin, which should prove of great interest to the student66 of archæology. In August, 1898, in a sandpit at Greenhills, Tallaght, County Dublin, workmen engaged in removing sand from the face of the pit discovered a cist; it measures 24 inches by 19 inches, and the height in the centre is 19 inches. It is formed of single stones two to four inches thick; the bottom stone is broken. It contained three vessels—a large urn inverted and covering a much smaller one, and a food-vessel of flower-pot shape. Under the urn was a quantity of burnt bones. Other urns and broken fragments of pottery, a skeleton, and portions of burnt bones were found in the same pit, which shows that both forms of disposing of the dead existed at the same period of time. The cist, encased in its matrix of sand and earth, was carefully and most successfully removed by Colonel Plunkett, director of the Museum, and his assistants. Expert opinion on the shape and decoration of the vessels places them at the close of the Bronze Period.

Note 33. Proceedings Roy. Ir. Acad., 3rd Series, vol. v., No. 3.

Howth Cromlech. This fine monument is situated near the base of an inland cliff, within the grounds of Howth Castle, and at a distance of about three-quarters of a mile from the sea-shore. It consists, at present, of ten blocks of quartzite rock; the table or covering stone is 20 feet long and 17 feet broad; it is 56 feet in circumference; and the extreme thickness is 8 feet. The weight of this mass has been computed at 70 tons. It seems as if the enormous pressure caused the supporters more or less to give way; they67 all incline westward, and the table appears as if it had slipped in that direction, in its course breaking one of the pillars in two. This probably occurred before the block could be placed in its intended position, and it was arrested in its descent by the undisturbed stump of the fractured stone upon which, in an inclined position, it now reposes at its lowest edge. Three of the supporters are about 8 feet high, so that, as Beranger, who visited and described the remains about a hundred years ago, states: 'This, one of the grandest mausoleums, must have made a noble figure standing, as the tallest man might stand and walk under it with ease.' The structure on the interior would seem to have constituted an irregular chamber, tending east and west; but much disturbance of the stones has occurred, and it would be now impossible by drawings and plans to give a very reliable idea of the original appearance of this still impressive pile, which, we may add, appears never to have been surmounted by cairn or tumulus of any68 kind. These stones were formerly called 'Fin Mac Coul's Quoits.'

Kilternan Cromlech [Map] is near Kilternan House, 7 miles from Dublin, and half a mile west of Golden Ball. It is another fine example of its class, when we consider the weight of its table, estimated at 40 tons, and the difficulty, as we must suppose, of raising, in a rude age, such a mass upon supporters. The covering stone, like all others, of this monument is of the granite of the district. Its measurements are: extreme length, 22 feet; width, 13½ feet; greatest thickness, 6 feet 6 inches. The supporters vary in height from 2 to 4 feet, but it is impossible to know how far they may be sunk below the present ground level. Some considerable disturbance in their arrangement appears to have occurred. Several would seem to have subsided, but the roofing69 block is still held above ground by the others; the height of the enclosure may be stated as about five feet from floor to roof. The plan of the chamber is very irregular, but it may be described as extending east and west. This cromlech is known as 'the giant's grave'; but there is no local tradition connected with it, folklore in this district having generations ago ceased to exist.

Mount Venus Cromlech [Map]. This monument, situated at Woodtown, about two and a half miles from Rathfarnham, a suburb of Dublin, is no longer perfect. Its table, which may have slipped from its original position, is at present supported by a single stone about 7½ feet in height, and of considerable massiveness. The greatest measurement of the covering stone is 23 feet; it is 12 feet in breadth, and 5 feet in thickness. It is supported at the north-west corner by an upright stone, forming with it an angle of 45°. Several of the former supporting stones would seem to have been removed, and others have evidently been broken. The rock is70 granite, of a very hard, close, and durable description. It seems to have weathered but little, as all the remaining stones present angles of considerable sharpness. Du Noyer was of opinion that this cromlech was of what he styled the 'earth-fast' class, and that the roof had always in part rested upon the ground. In this supposition O'Neill, no mean authority on such matters, did not by any means coincide. The weight of the covering stone is estimated at 42 tons. So great a pressure might well cause some of the weaker supporters to give way, in which case the pile would very probably assume its present appearance. It is not in the least likely that this tomb had at any time been covered by a tumulus or cairn. Mr. Borlase considers it 'one of the most magnificent megalithic monuments in the world.'

Shanganagh Cromlech [Map]. At Shanganagh, half a mile to the east of the hamlet of Loughlinstown, may be seen a fine specimen of what may be styled, as regards size, a cromlech of the second class. It is supported upon four stones, and presents no appearance of having been enveloped in a mound of any description. Like nearly every one of its kindred remains in the County Dublin, it is formed of granite blocks. The covering stone measures 9 feet in length by 7 feet at its greatest breadth; it is 3½ feet in its extreme thickness; and its highest portion is at present slightly over 9 feet above the ground; the weight is about 12 tons. The chamber would seem to extend east and west. The cromlech may be easily visited from Killiney railway station.

Brennanstown (Glen Druid) Cromlech [Map]. In a picturesque valley, close to Cabinteely, County Dublin, stands a very perfect cromlech. This monument may be reached in a short walk from the Carrickmines railway station. The site is a little over one mile and a-half from the sea-coast. The covering stone is of an irregular form, but the under portion, which forms the top of the chamber, is quite flat and horizontal. The following are its dimensions: length and breadth, 15½ feet; thickness, 3 to 5 feet. It is not easy to calculate the weight of this mass, on account of the irregularity of form which the block presents; but it is estimated at 36 tons. It rests, as Mr. Borlase points out, on two antæ, as well as on the larger stones, and so forms an ante-chamber 5 feet wide at the entrance. A number of detached stones lying72 about this very perfect example would indicate that it was originally accompanied by a circle of standing stones.

Glensouthwell Cromlech. Of this 'Druid's or Brehon's Chair,' already referred to (page 42), Beranger wrote as follows: 'This piece of antiquity, the only one yet discovered, is situated at the foot of the Three-Rock Mountain. It is supposed to be the seat of judgment of the Arch-Druid, from whence he delivered his oracles. It has the form of an easy-chair wanting the seat, and is composed of three rough, unhewn stones, about 7 feet high, all clear above ground. How deep they are in the earth remains unknown. Close to it is a sepulchral monument or cromlech, supposed to be the tomb of the Arch-Druid.73 It is 15 feet in girth, and stands on three supporters, about 2 feet high, and is planted round with trees. The top stone is 8½ feet long.' The so-called 'chair' still remains, and the above account fairly describes it. The three stones, standing north, west, and east, are, however, 9¼ feet, 8¾ feet, and 8 feet high, respectively. It never was a 'chair.' It is evidently a rather small but high cromlech that has lost its covering stone. The 'cromlech' noticed by Beranger was probably the block destroyed by blasting in 1876.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Glencullen Cromlech. This monument is situated on the eastern side of Glencullen, half a mile north-west of Glencullen House, near Kilternan, in a very wild district, extending to the west of the Three-Rock Mountain, and at a distance of some three miles, in a direct line, from the sea. It is described by O'Neill as having 'a roof rock 10 feet long, 8 feet broad, and 4 feet thick, extreme measures.... The longest direction of the roof rock is W.S.W., or nearly east and west. The chamber is greatly damaged.'34

Note 34. The three distinct groups of rocks on the Three-Rock Mountain, a familiar natural feature from the suburbs of Dublin, were considered by Beranger to be 'Druidical remains.' From a distance they appear like cairns, but they were never raised by human hands, and their interest is entirely geological.

Ballyedmond Chamber is ¾ of a mile north-west of Glencullen House, in the parish of Kilgobbin. O'Curry, writing of it, says: 'It is a very fine giant's grave, resembling the Bed of Callan More on Slieve Gullion, only that it is more perfect. I doubt if we have met74 so perfect a pagan grave in any other counties hitherto examined. This had been a tumulus, and the earth being cleared away, the grave was to be seen. The tumulus was oval in shape, and its axis, like that of the grave, was east and west.' The side stones of the chamber were ten in number, one of the covering stones, measuring 7 feet by 5, remained in its place.

Shankill Cromlech. In Cromwell's Excursions through Ireland, vol. III., p. 159, there is an engraving, after a drawing by Petrie, of a dolmen at this place, which is situated about four miles to the north or north-west of Bray, at a distance of a couple of miles from the nearest point of the sea-shore. O'Neill, writing in 1852, says that he could not find it, and heard that it had been removed a few years previously. Nevertheless the monument still exists, and was sketched by Mr. Wakeman some years ago. It stands by the side of a road leading across the eastern slope of Carrigollagher, in the direction of Rathmichael, and is a fair specimen of its class. It retains its covering stone in situ, but without the end stones.

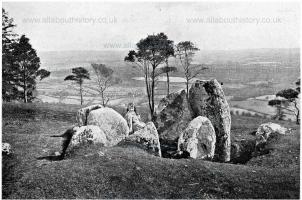

It is interesting to note that the cromlechs in the east of Ireland are generally of the free-standing and uncovered class. If we want to find similar monuments to those mentioned, we must seek for them much further north, or in districts of the west or south-west of Ireland. It was known that in County Sligo scores of these subaerial sepulchral monuments were to be found surrounded by one or more lines of stones, which are not unfrequently associated with free-standing pillar-stones,75 and, as would sometimes seem, with elementary alignments. But, until the appearance of Colonel Wood-Martin's Rude Stone Monuments of Sligo and Achill, it was not known that in the west existed T-shaped sepulchres, and others in plan like a dumb-bell, the handle representing the grave, while the bulbous ends might be expressed in the form of regularly-constructed stone circles. He was also enabled to point to triangular graves, a form of burial structure in Ireland previously described by no other writer. 'It is remarkable,' says Colonel Wood-Martin, 'that, in the county of Sligo, the characteristic features of the megaliths varied according to districts: for example, in Carrowmore the circular form was almost universal, whereas in Northern Carbury an oblong arrangement appears to predominate. Again, in the Deerpark Monument, the general architectural principles displayed at Stonehenge can be traced.' In the townland of Carrowmore, to the south-west of Sligo, here referred to, are, or were, the remains, says Mr. Borlase, of sixty-five 'dolmen circles,' forty-four of which are designated in the Ordnance Survey Map. For particulars of these we must refer the reader to Colonel Wood-Martin's survey and Mr. Borlase's work. Before finally leaving the subject of the ordinary cromlech it is necessary to notice some examples which bear markings, seemingly carved with some intention.

Knockmany Chamber [Map]. This interesting sepulchral monument, which is illustrated in the frontispiece to this work, is on the summit of a wooded hill, about76 two and a half miles north of Clogher, County Tyrone. The chamber is of the type known as the 'giant's grave'; it lies nearly due north and south, and consists of thirteen stones, most of which are mill-stone grit. None of the covering stones now remain, having probably been removed for building purposes. The tomb seems to have been originally covered by a mound. The internal measurement is 10 feet 3 inches by 6 feet 6 inches; two of the blocks of the east side have fallen inwards. Four of the stones have markings, consisting of cup-hollows, zigzag lines, concentric circles, and other curved patterns. Expert opinion, from an examination of their forms, is inclined to associate the markings with the later Bronze Age of Scandinavia, and to give a probable date of this sepulchral chamber as 500 B.C. The tomb is known locally as 'Aynia's Cove,' popular superstition associating it with a witch or hag named Aynia or Ainé. It is also called Knoc Baine, as being the supposed burial-place of Baine, mother of Feidhlimidh Reachtmhar, who was king of Ireland early in the second century. This would bring the monument to the Late Celtic period, which is difficult to reconcile with the archæological evidence already mentioned, associating it with the Bronze Age.35

Note 35. Journal Roy. Soc. of Antiq. Ir., 1896, p. 93; and 1876, p. 95.

Cloghtogh Cromlech. Cloghtogh, the 'Lifted stone,' is situated close to the village of Lisbellaw, Co. Fermanagh. It consists of four great stones, two of which form the sides, and one the end, of a quadrangular chamber. On the front of the fourth stone, which constitutes the77 cap or covering, were four well-marked cups, averaging 1¾ inches in diameter. These, which unfortunately have been chipped off, were placed in a horizontal line, extending over a space of 18 inches, and slightly diminishing in size from left to right. The block is 7½ feet in length, by 6 feet in breadth, the thickness being 1½ feet.

Slievemore Cromlech. Similar markings may be observed on one of the upright stones of a ruined cromlech standing on the slope of Slievemore, island of Achill, amongst other remains, styled on the Ordnance sheet tumulus, cromlech, Danish ditch, respectively. It is difficult to imagine that the likeness between these two sets of cup-markings is accidental. A similar array of four cups, but placed vertically, may be seen on one of the enormous stones forming the right-hand side of the gallery leading into the great cairn of Newgrange.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Lennan Cromlech. The inscribed cromlech of Lennan or Tullycorbet, Co. Monaghan, stands upon a knoll called by the people of the district Cruck-na-clia, which may be translated 'Battle hill.' This monument, a fine one of its class, presents every appearance of having always been free-standing. It bears some extremely curious markings, into the character of which the late Sir Samuel Ferguson made careful examination.36

Note 36. Journal Roy. Soc. of Antiq. Ir., 1872, p. 523.

Castlederg Cromlech. This monument lies about three-quarters of a mile to the north of the town of Castlederg,78 140 yards to the east of the old Strabane road, leading through Churchtown townland. The principal cap-stone was dislodged many years ago by the owner of the farm. 'It appears,' says Sir Samuel Ferguson, 'that the structure had previously been rendered insecure by a stone-mason, who had abstracted one of the supporters for building purposes; and it was suggested that the motive for casting down the cap-stone was an apprehension lest the owner's cattle, in rubbing or sheltering under it, might do themselves a mischief. That the inscription was there at the time of the first disclosure of the upper face of the support on which it is sculptured, is the common and constant statement of the people of the country; but the case rests more satisfactorily on the fact, wholly independent of testimony, that a collateral covering stone remains in situ, and that the line of scorings is prolonged underneath it into a position too contracted for the use of a graving tool.'37

Note 37. Journal Roy. Soc. Antiq., 1872, p. 526.

The work here consists of a continuous series of straight scorings, accompanied by a number of dots or depressions more or less circular in form. There can be no doubt that a generic resemblance may be noticed between them and many of the markings of the Lennan inscription. This, if there were nothing more, would raise a serious doubt of their being merely accidental or capricious indentations. The great majority of such irregular scorings should, nevertheless, be looked upon with suspicion. Those which occur on the pillar-stone at Kilnasaggart, Co. Armagh, though long considered to be Ogam characters, are now universally pronounced to79 be nothing more than markings made by persons who utilized the monument as a block for the sharpening and pointing of tools or weapons. The same remark applies in full force to certain scorings and scratches which disfigure a fine pillar-stone standing close to the railway station of Kesh, County Fermanagh, on the right-hand side of the line as you face towards Bundoran. They are found abundantly on the coping stones of the walls of Londonderry, and indeed in other localities too numerous to mention. At Killowen, County Cork, they occur on a stone most significantly called Cloch na n'Arm, or the '(Sharpening) Stone of the weapons.'