Text this colour is a link for Members only. Support us by becoming a Member for only £3 a month by joining our 'Buy Me A Coffee page'; Membership gives you access to all content and removes ads.

Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, a canon regular of the Augustinian Guisborough Priory, Yorkshire, formerly known as The Chronicle of Walter of Hemingburgh, describes the period from 1066 to 1346. Before 1274 the Chronicle is based on other works. Thereafter, the Chronicle is original, and a remarkable source for the events of the time. This book provides a translation of the Chronicle from that date. The Latin source for our translation is the 1849 work edited by Hans Claude Hamilton. Hamilton, in his preface, says: "In the present work we behold perhaps one of the finest samples of our early chronicles, both as regards the value of the events recorded, and the correctness with which they are detailed; Nor will the pleasing style of composition be lightly passed over by those capable of seeing reflected from it the tokens of a vigorous and cultivated mind, and a favourable specimen of the learning and taste of the age in which it was framed." Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries is in Prehistory.

Books, Prehistory, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries V2 1883

Books, Prehistory, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries V2 1883 Pages 275-279

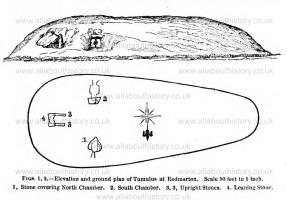

The Rev. samuel Lysons, F.S.A., gave an account of the opening of a tumulus [Windmill Tump aka Rodmarton Long Barrow [Map]] on his property at Rodmarton, in Gloucestershire, of which the following are the particulars. The tumulus was of the kind known as long barrows; its extreme length was 176 feet; greatest width 71 feet; height about 10 feet. (See figs. 1, 2.) It lay nearly due east and west.

Its popular name, "Windmill Tump," had probably diverted the attention of previous antiquaries, such as the Rev. S. Lysons and D. Lysons, Esq., the uncles of the present owner.

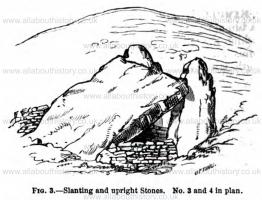

The surface-earth having been removed at the east end, the mound appeared to be composed of rubble stone of the country, not thrown together at hap-hazard, but as though dry walls had been erected ay the tumulus, so as to support the rubble stones, and prevent them falling. A few feet below the surface the workmen discovered two large unhewn stones, placed upright in the ground, opposite to each other; each of them measured 8 feet 6 inches in height (Fig. 3.) Against these was leaning a third stone, of large size, which was found to be supported on each side by a low dry wall, and could not therefore have slipped off from the other stones, as might otherwise have been surmised. The position of this stone is exactly similar to one in a cromlech in the county Kilkenny, Ireland, published in the Archæologia, vol. xvi. pl. xviii, and also to one at Molfra [Map] in Cornwall, of which a model is to be seen in the British Museum. Another dry wall filled in the space between the two upright stones.

Beneath these were discovered a quantity of animals’ bones, including the teeth of horses, boars’ tusks, and jaws of calves. No human bones appeared in this part of the tumulus, but a cer- tain quantity of powdered charcoal.

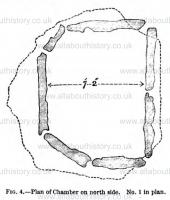

The next investigation was made at the northern shoulder of the mound, where was discovered a chamber with a paved floor; the sides were formed by seven large upright stones, and the top by an immense ingle stone, measuring nearly nine feet by eight, about eighteen inches thick, and weighing probably eight or nine tons. (Fig. 4.)

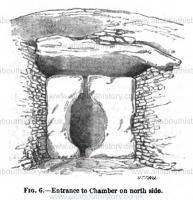

This chamber was approached by a very narrow passage inclosed by low dry walls on each side. The entrance was closed nearly up to the roof by a barrier formed of two stones placed side by side upright in the ground, and hollowed out on their two inner and adjoining edges so as to leave a kind of port- hole of an oval shape (fig. 6), similar to that in the tumulus at Avening (Archæologia, vol. xvi. p. 362, pl. lvii.). This openin was itself protected and closed up by another upright stone placed in front of it, which had to be removed before the chamber could be entered.

Within lay on the floor the skeletons of no less than thirteen persons, apparently of both sexes and all ages. Among the bones were discovered the following objects:

1. Five small flint implements; two of them leaf-shaped and finely wrought, which appeared to have been arrow-heads ; the other three were flakes of the usual character, and might have been knives.1

2. A large piece of natural flint, which must have been brought some distance, as there is none of this character to be found within twenty miles of the spot.

3. The débris of a vesscl of very coarse pottery, nearly black.

4. A large stone of a grit not found in the neighbourhood.

5 A small round pebble of a white material.

Although most of the human bones exhibited no traces of cremation, some few had been burnt. The bones were all in great confusion, and some had been dragged into a corner. This had probably been done by some beasts of prey, either foxes or rats.2

Note 1. Compare the flint implements found in a tumulus at Broughton in Lincolnshire. (Archæological Journal, vol. viii. p. 344.) Also for the leaf-shaped, Wilde's Catalogue of the Royal Irish Academy, figs. 22, 23, p. 22.

Note 2. Mr. Lysons opened subsequently, in the month of October, a second chamber in the southern shoulder of the mound; it had evidently been rifled on some former occasion. Human bones were found in quantities, mixed with earth, and had evidently been thrown in again in confusion. The structure of the chamber was much the same as that on the other side, excepting that it had nine stones instead of five, and that the top stone was broken (see fig. 5, No. 2 on plan).

Indications were found of former attempts to examine the mound, such as depressions, especially in the centre. The time at which these attempts had been made seemed to be due to the Romans, as there were found an iron ferrule of a spear, a horse-shoe nail, and two small coins, one of them struck by Claudius Gothicus.

The skulls found in the chamber have been examined by John Thurnam, Esq., M.D., F.S.A., who has pronounced them to be ancient British of a very lengthened form. Several of them appeared to have received fractures during life of a kind which must at once have proved fatal.

The author further proceeded to illustrate these discoveries, and the peculiarities to be noticed in them from various passages in Scripture, and in classical authors ; the whole of which will appear In a forthcoming work.

The curious long barrows which have so long perplexed Archæologists have formed the subjects of several communications to the Society. Those in Wiltshire are noticed by Mr. Cunnington in the Archaologia, vol. xv. p. 346: that at Avening in Gloucestershire, in Archæologia, vol. xv. p. 362; that at Stoney Littleton in the parish of Wellow, Somersetshire, by Sir R. C. Hoare, Archzologia, vol. xix. p. 43; and that at West Kennet in Wiltshire by Dr. Thurnam, in Archaologia, vol. xxxviii. p. 405. The long barrow at Uley in Gloucestershire has been described by Dr. A in the Archwological Journal, vol. xi. p. 315; that at Littleton Drew, Wiltshire, in the Wilts Archeological Magazine, vol. iii. p. 164, also by Dr. Thurnam (compare Crania Britannica, plates 5, 24, 50, and 59); and the analogous struc- tures in Guernsey have been noticed by F. C. Lukis, oy in the Archaeological Toni, vol. i. p. 142, 222; and in the Journal of the British Archazological Association, vol. i. p. 23, and vol. iv. p- 330.

Thanks were returned for these Communications.

Books, Prehistory, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries V9 1883

Winterborne-Bassett. I produce a ground plan of a circular monument, situated 3½ miles north of Avebury, which Stukeley has briefly described: 'In a field, north-west of the church [of Winterbourne-Bassett], upon elevated ground, is a double circle, concentric, 60 cubits diameter. The two circles are near one another, so that one may walk between. Many of the stones have of late been carried away. West of it is a single, broad, flat, and high stone, standing by itself, and about as far northward from the circle, in a plowed field, is a barrow set round with, or rather composed of, large stones.' — (Abury, p. 45.)

Sir R. C. Hoare writes (Ancient Wilts, vol. ii. p. 95): 'By the above description I was enabled to find the remains of this circle, which is situated in a pasture ground at the angle of a road leading to Broad Hinton, and consists at present only of a few inconsiderable stones.' As Stukeley and Sir R. C. Hoare have not given plans, nor stated how many stones, whether standing or fallen, composed the double circle, we have no means of judging what was its appearance. Not one stone is now standing, and only six are visible, and one or two of these are barely above ground. By probing we found eleven buried stones, which we uncovered. Some of them appear to be very near to their original places in the circles, and others have been displaced.

Stukeley’s '60 cubits diameter' [110 feet, according to his measure of a cubit] is clearly an error for radius, for it will be seen from the plan on the table that the diameter of the outer circle is about 240 feet, and that of the inner 165 feet.

The stones are small, and the monument can only have been imposing by reason of its large size. A prostrate stone occupies the centre of the circles, and in this respect we are reminded of two Cornish circles which have a like feature. It is possible, but scarcely probable, that this stone belonged to the inner circle, left here in course of removal, and yet if it was in the centre when Stukeley visited the monument, it is strange that he should have been silent respecting it, with his keen eye for keblas and coves.

The menhir, west of the circle, and the barrow northward, have disappeared; but in the same field with the circles, and at a distance of 253 feet from the centre of them, in a direction south-south-east, is a large stone, lying upon the ground, 9 feet long, 7 feet wide; and at a distance of 351 feet east-north-east from the centre are two fallen stones much buried. These three stones are not alluded to by Stukeley and Hoare.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.