Biography of John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury 1350-1400

Paternal Family Tree: Montagu

On 24 Jun 1340 King Edward III of England (age 27) attacked the French fleet at anchor during the Battle of Sluys capturing more than 200 ships, killing around 18000 French. The English force included John Beauchamp 1st Baron Beauchamp Warwick (age 24), William Bohun 1st Earl of Northampton (age 30), Henry Scrope 1st Baron Scrope Masham (age 27), William Latimer 4th Baron Latimer of Corby (age 10), John Lisle 2nd Baron Lisle (age 22), Ralph Stafford 1st Earl Stafford (age 38), Henry of Grosmont 1st Duke Lancaster (age 30), Walter Manny 1st Baron Manny (age 30), Hugh Despencer 1st Baron Despencer (age 32) and Richard Pembridge (age 20).

[his grandfather] Thomas Monthermer 2nd Baron Monthermer (age 38) died from wounds. His daughter [his mother] Margaret Monthermer Baroness Montagu 3rd Baroness Monthermer succeeded 3rd Baroness Monthermer.

Before 1350 [his father] John Montagu 1st Baron Montagu, Baron Monthermer (age 20) and [his mother] Margaret Monthermer Baroness Montagu 3rd Baroness Monthermer were married. She by marriage Baroness Montagu. He by marriage Baron Monthermer. He the son of William Montagu 1st Earl Salisbury and Catherine Grandison Countess of Salisbury. She a great granddaughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

Around 1350 John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury was born to John Montagu 1st Baron Montagu, Baron Monthermer (age 20) and Margaret Monthermer Baroness Montagu 3rd Baroness Monthermer. He a great x 2 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

In or after 1356 Alan Buxhull (age 33) and [his future wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury were married. She reputed to be the richest woman in England at the time. The difference in their ages was 41 years.

In 1357 [his father] John Montagu 1st Baron Montagu, Baron Monthermer (age 27) was created 1st Baron Montagu.

Before 1372 John Aubrey and [his future wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 7) were married.

Before 13 Jun 1388 John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 38) and Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 24) were married. He a great x 2 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

On 13 Jun 1388 [his son] Thomas Montagu 1st Count Perche 4th Earl Salisbury was born to John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 38) and [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 24). He a great x 3 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

In 1389 [his father] John Montagu 1st Baron Montagu, Baron Monthermer (age 59) died. His son John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 39) succeeded 2nd Baron Montagu.

In 1389 [his son] Richard Montagu was born to John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 39) and [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 25). He a great x 3 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

In 1395 [his mother] Margaret Monthermer Baroness Montagu 3rd Baroness Monthermer died. In 1395 Her son John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 45) succeeded 4th Baron Monthermer. [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 31) by marriage Baroness Monthermer.

On 03 Jun 1397 [his uncle] William Montagu 2nd Earl Salisbury (age 68) died. His nephew John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 47) succeeded 3rd Earl Salisbury, 5th Baron Montagu. [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 33) by marriage Countess Salisbury.

Froissart. After 12 Jul 1397. The earl of Salisbury (age 47) was very earnest in his supplications for the earl of Warwick (age 59). They had been brothers in arms ever since their youth; and he excused him on account of his great age, and of his being deceived by the fair speeches of the duke of Gloucester (age 42) and the earl of Arundel (age 51): that what had been done was not from his instigation, but solely by that of others; and the house of Beauchamp, of which the earl of Warwick was the head, never imagined treason against the crown of England. The earl of Warwick (age 59) was, therefore, through pity, respited from death, but banished to the Isle of Wight [Map], which is a dependency on England. He was told, - "Earl of Warwick (age 59), this sentence is very favourable, for you have deserved to die as much as the earl of Arundel (age 51), but the handsome services you have done in times past, to king Edward of happy memory, and the prince of Wales his son, as well on this as on the other side of the sea, have secured your life; but it is ordered that you banish yourself to the Isle of Wight, taking with you a sufficiency of wealth to support your state as long as you shall live, and that you never quit the island." The earl of Warwick (age 59) was not displeased with this sentence, since his life was spared, and, having thanked the king and council for their lenity, made no delay in his preparations to surrender himself in the Isle of Wight on the appointed day, which he did with part of his household. The Isle of Wight is situated opposite the coast of Normandy, and has space enough for the residence of a great lord, but he must provide himself with all that he may want from the circumjacent countries, or he will be badly supplied with provision and other things.

In 1398 John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 48) was appointed 89th Knight of the Garter by King Richard II of England (age 30).

Froissart. Before 19 Oct 1398. Not long after this, the king of England (age 31) summoned a large council of the great nobles and prelates at Eltham [Map]. On their arrival, he placed his two uncles of Lancaster (age 58) and York (age 57) beside him, with the earls of Northumberland (age 56), Salisbury (age 48) and Huntingdon (age 46). The earl of Derby (age 31) and the earl marshal (age 30) were sent for, and put into separate chambers, for it had been ordered they were not to meet. The king (age 31) showed he wished to mediate between them, notwithstanding their words had been very displeasing to him, and ought not to be lightly pardoned. He required therefore that they should submit themselves to his decision; and to this end sent the constable of England, with four great barons, to oblige them to promise punctually to obey it. The constable and the lords waited on the two earls, and explained the king's intentions They both bound themselves, in their presence, to abide by whatever sentence the king should give. They having reported this, the king said,- "Well then, I order that the earl marshal (age 30), for having caused trouble in this kingdom, by uttering words which he could not prove otherwise than by common report, be banished the realm: he may seek any other land he pleases to dwell in, but he must give over all hope of returning hither, as I banish him for life. I also order, that the earl of Derby (age 31), our cousin, for having angered us, and because he has been, in some measure, the cause of the earl marshal's (age 30) crime and punishment, prepare to leave the kingdom within fifteen days, and be banished hence for the term of ten years, without daring to return unless recalled by us; but we shall reserve to ourself the power of abridging this term in part or altogether." The sentence was satisfactory to the lords present, who said: "The earl of Derby (age 31) may readily go two or three years and amuse himself in foreign parts, for he is young enough; and, although he has already travelled to Prussia, the Holy Sepulchre, Cairo and Saint Catherine's1, he will find other places to visit. He has two sisters, queens of Castillo (age 25) and of Portugal (age 38), and may cheerfully pass his time with them. The lords, knights and squires of those countries, will make him welcome, for at this moment all warfare is at an end. On his arrival in Castille, as he is very active, he may put them in motion, and lead them against the infidels of Granada, which will employ his time better than remaining idle in England. Or he may go to Hainault, where his cousin, and brother in arms, the count d'Ostrevant, will be happily to see him, and gladly entertain him, that he may assist him in his war against the Frieslanders. If he go to Hainault, lie can have frequent intelligence from his own country and children. He therefore cannot fail of doing well, whithersoever he goes; and the king (age 31) may speedily recall him, through means of the good friends he will leave behind, for he is the finest feather in his cap; and he must not therefore suffer him to be too long absent, if he wish to gain the love of his subjects. The earl marshal (age 30) has had hard treatment, for he is banished without hope of ever being recalled; but, to say the truth, he has deserved it, for all this mischief has been caused by him and his foolish talking: he must therefore pay for it." Thus conversed many English knights with each other, the day the king passed sentence on the earl of Derby (age 31) and the earl marshal (age 30).

Note 1. The monastery on Mount Sinai. - Ed.

Froissart. After 19 Oct 1398. When the day of his exile drew near, he went to Eltham where the king (age 31) resided. He found there his father (age 58), the duke of York (age 57) his uncle, and with them the earl of Northumberland (age 56), sir Henry Percy (age 34) his son, and a great many barons and knights of England, vexed that his ill fortune should force him out of England. The greater part of them accompanied him to the presence of the king (age 31), to learn his ultimate pleasure as to this banishment. The king (age 31) pretended that he was very happy to see these lords: he entertained them well, and there was a full court on the occasion. The earl of Salisbury (age 48), and the earl of Huntingdon (age 46), who had married the duke of Lancaster's (age 58) daughter (age 35), were present, and kept near to the earl of Derby (age 31), whether through dissimulation or not I am ignorant. When the time for the earl of Derby's (age 31) taking leave arrived, the king (age 31) addressed his cousin with great apparent humility, and said, "that as God might help him, the words which had passed between him and the lord marshal had much vexed him; and that he had judged the matter between them to the best of his understanding, and to satisfy the people, who had murmured greatly at this quarrel. Wherefore, cousin," he added, "to relieve you somewhat of your pain, I now remit four years of the term of your banishment, and reduce it to six years instead often. Make your preparations, and provide accordingly." "My lord," replied the earl, "I humbly thank you; and, when it shall be your good pleasure, you will extend your mercy." The lords present were satisfied with the answer, and for this time were well pleased with the king's (age 31) behaviour, for he received them kindly. Some of them returned with the earl of Derby (age 31) to London. The earl's baggage had been sent forward to Dover, and he was advised by his father, on his arrival at Calais, to go straight to Paris, and wait on the king of France (age 29) and his cousins the princes of France, for by their means he would be the sooner enabled to shorten his exile than by any other. Had not the duke of Lancaster earnestly pressed this matter, like a father anxious to console his son, he would have taken the direct road to the count d'Ostrevant in Hainault.

On 17 Dec 1399 the conspirators met at Abbey House Westminster Abbey [Map] including Thomas Blount (age 47), Thomas Despencer 1st Earl Gloucester (age 26), Thomas Holland 1st Duke Surrey (age 25), John Holland 1st Duke Exeter (age 47), Ralph Lumley 1st Baron Lumley (age 39), John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 49), Edward York 2nd Duke of York 1st Duke Albemarle (age 26), Bernard Brocas (age 45). They plotted to capture King Henry IV of England (age 32) at a Tournament in Windsor, Berkshire [Map] on the Feast of Epiphany hence the Epiphany Rising.

On 07 Jan 1400 at Cirencester, Gloucestershire [Map] Ralph Lumley 1st Baron Lumley (age 40) was beheaded by the townspeople following an unsuccessful attempt to seize the town. Baron Lumley forfeit.

Thomas Holland 1st Duke Surrey (age 26) was beheaded. He had to forfeit the honours and estates he had gained after the arrests of Gloucester and Arundel: Duke Surrey extinct. He retained those he had received before: His brother Edmund Holland 4th Earl Kent (age 16) succeeded 4th Earl Kent, 3rd Baron Holand, 8th Baron Wake of Liddell.

John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 50) was captured, tried and beheaded. Earl Salisbury, Baron Montagu, Baron Montagu forfeit.

Bernard Brocas (age 46) was captured.

Before 07 Jan 1400 [his daughter] Margaret Montagu Baroness Ferrers Groby was born to John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 50) and [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 36). She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

Before 07 Jan 1400 [his son] Robert Montagu was born to John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 50) and [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 36). He a great x 3 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

Before 07 Jan 1400 [his daughter] Anne Montagu Duchess Exeter was born to John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 50) and [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 36). She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

Before 07 Jan 1400 [his daughter] Elizabeth Montagu Baroness Willoughby Eresby was born to John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury (age 50) and [his wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 36). She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

After 07 Jan 1400. Henry IV's (age 32) Parliament. Also, be it remembered that whereas Thomas Holland, formerly earl of Kent (deceased), John Holland, formerly earl of Huntingdon (age 48), John Montague, formerly earl of Salisbury (deceased), Thomas, formerly Lord Despenser (age 26), and Ralph Lumley (deceased), knight, recently rose up in various parts of England and rode in warlike manner, treacherously, against our lord the king (age 32), contrary to their allegiance, to destroy our said lord the king and other great men of the realm, and to populate the said realm with people of another tongue, they were seized and beheaded in their armed uprising by the loyal lieges of oursaid lord the king; and for that reason all the lords temporal present in parliament, by the assent of the king, declared and adjudged the said Thomas, John, John, Thomas, and Ralph to be traitors for their armed uprising against their aforesaid liege lord, and that they should forfeit as traitors all the lands and tenements that they held in fee simple on 5 January, the eve of the feast of the Epiphany of our lord Jesus Christ, in the first year of the reign of our aforesaid lord [1400], or after, as the law of the land requires, together with all their goods and chattels, notwithstanding the fact that they were killed during the said armed uprising without due process of law.

On 30 Jul 1424 [his former wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury (age 60) died.

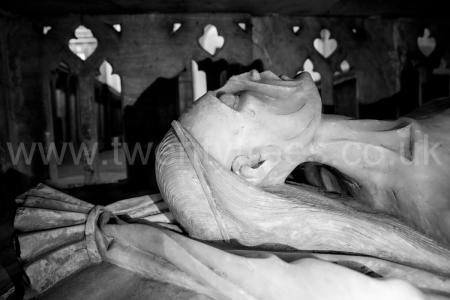

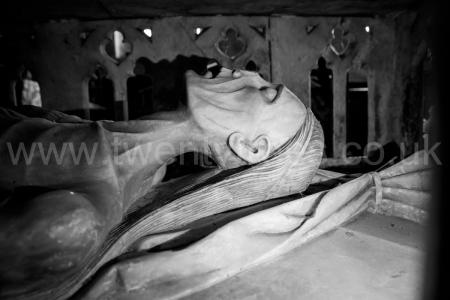

After 20 May 1475. St Mary's Church, Ewelme [Map]. Monument to Alice Chaucer Duchess Suffolk (deceased). Wrist Garter. The effigy was, apparently, viewed to determine how a lady should wear the garter at the re-commencement of Lady of the Garter appointments in 1901 after a gap of several hundred years. A particularly fine Cadaver Underneath the chest on which Alice's effigy lies. Full-length in a shroud. Chest with Angels with Rounded Wings holding Shields.

Detail of the South Side of the Monument to Alice Chaucer Duchess Suffolk (deceased).

1  Roet Arms impaled

Roet Arms impaled  Chaucer Modern Arms. Alice's paternal grandparents.

Chaucer Modern Arms. Alice's paternal grandparents.

2  De La Pole Arms impaled

De La Pole Arms impaled  Stafford Arms. Her third husbands parents Michael de la Pole 2nd Earl Suffolk and Katherine Stafford Countess Suffolk.

Stafford Arms. Her third husbands parents Michael de la Pole 2nd Earl Suffolk and Katherine Stafford Countess Suffolk.

3  Montacute and Monthermer Arms impaled Francis? Possibly Alice's second husband's parents John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury and [his former wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury.

Montacute and Monthermer Arms impaled Francis? Possibly Alice's second husband's parents John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury and [his former wife] Maud Francis Countess of Salisbury.

4  De La Pole Arms quartered

De La Pole Arms quartered  Chaucer Modern Arms.

Chaucer Modern Arms.

5  Roet Arms quartered

Roet Arms quartered  Chaucer Modern Arms.

Chaucer Modern Arms.

8  De La Pole Arms impaled

De La Pole Arms impaled  England Henry IV Arms signifying Alice's son John's (age 32) marriage to Elizabeth of York (age 31) sister of King Edward IV of England (age 33).

England Henry IV Arms signifying Alice's son John's (age 32) marriage to Elizabeth of York (age 31) sister of King Edward IV of England (age 33).

Detail of the North Side of the monument to Alice Chaucer Duchess Suffolk (deceased). Arms from left to right ...

1  De La Pole Arms quartered

De La Pole Arms quartered  Chaucer Modern Arms impaled Unknown.

Chaucer Modern Arms impaled Unknown.

2  De La Pole Arms impaled

De La Pole Arms impaled  Chaucer Modern Arms. Her third husband William "Jackanapes" de la Pole 1st Duke of Suffolk.

Chaucer Modern Arms. Her third husband William "Jackanapes" de la Pole 1st Duke of Suffolk.

3  De La Pole Arms quarted

De La Pole Arms quarted  Chaucer Modern Arms. Alice's son John de la Pole 2nd Duke of Suffolk (age 32) by her second husband William "Jackanapes" de la Pole 1st Duke of Suffolk.

Chaucer Modern Arms. Alice's son John de la Pole 2nd Duke of Suffolk (age 32) by her second husband William "Jackanapes" de la Pole 1st Duke of Suffolk.

5  Montacute and Monthermer Arms quartering impaled Chaucer. Alice's second husband [his son] Thomas Montagu 1st Count Perche 4th Earl Salisbury.

Montacute and Monthermer Arms quartering impaled Chaucer. Alice's second husband [his son] Thomas Montagu 1st Count Perche 4th Earl Salisbury.

6  Roet Arms. Alice's paternal grandmother Philippa Roet.

Roet Arms. Alice's paternal grandmother Philippa Roet.

7  England Henry IV Arms impaling

England Henry IV Arms impaling  Roet Arms probably signifying John of Gaunt 1st Duke Lancaster and Katherine Roet Duchess Lancaster, Katherine being the sister of Alice's paternal grandmother Philippa Roet who married Geoffrey Chaucer.

Roet Arms probably signifying John of Gaunt 1st Duke Lancaster and Katherine Roet Duchess Lancaster, Katherine being the sister of Alice's paternal grandmother Philippa Roet who married Geoffrey Chaucer.

8  Roet Arms impaling

Roet Arms impaling  Chaucer Modern Arms. Her paternal grandparents Geoffrey Chaucer and Philippa Roet.

Chaucer Modern Arms. Her paternal grandparents Geoffrey Chaucer and Philippa Roet.

Katherine Stafford Countess Suffolk: Around 1376 she was born to Hugh Stafford 2nd Earl Stafford and Philippa Beauchamp Countess Stafford. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England. Before 1394 Michael de la Pole 2nd Earl Suffolk and she were married. She by marriage Countess Suffolk. She the daughter of Hugh Stafford 2nd Earl Stafford and Philippa Beauchamp Countess Stafford. He the son of Michael de la Pole 1st Earl Suffolk and Katherine Wingfield Countess Suffolk. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England. On 08 Apr 1419 Katherine Stafford Countess Suffolk died.

Philippa Roet: Around 1346 she was born to Giles "Payne" Roet. Before 1367 Geoffrey Chaucer and she were married at St Mary de Castro Leicester, Leicestershire. Excerpta Historica Page 152. Philippa, his eldest daughter, is stated to have been the maid of honour to Philippa Queen of Edward the Third who by the name of "Philippa Pycard" obtained a grant of one hundred shillings per annum on the 20th January 1370, and married Geoffrey Chaucer, to whom, in consequence, it is supposed, of this connexion, the Duke of Lancaster granted the Castle of Dodington. Of John of Gaunt's connexion with Chaucer, however, no proof has been found; and the circumstance of the lady assigned to him for his wife being styled "Philippa Pycard," instead of Roelt, renders the assertion, that she was the sister of the Duchess of Lancaster, extremely doubtful. Around 1387 Philippa Roet died.

Calendars. 26 Sep 1484. Grant, for the peace and tranquillity of the city, to the mayor and commonalty of London and their successors, that if the king should hereafter deal in mercy with the lives of John Norhampton, draper, late mayor of London, John More, mercer, and Richard Norbury, who with others lately made insurrection against the king's peace and Nicholas Brembre, the mayor, and the governors of the city and its government, for which they were indicted and, after acknowledging their misdeeds before the king and council in his presence and being separately arraigned before John de Monte Acuto, steward of the household and the other justices assigned to deliver the prison of the Tower of London [Map] of them, were condemned to be drawn and quartered, but execution, so far as their lives were concerned, was respited by the king's grace,-that they shall be sent to prisons in different counties 100 leagues distant from the city for ten years, and not then be released until they have found security that no evil or prejudice shall befall the city or any of the king's lieges thereby. If they should be released they are inhibited, under pain of losing their lives, from coming within 100 leagues of the city, and any one guilty of making suit or maintenance on their behalf is to be imprisoned and forfeit his goods. For the strengthening of good government in the city and for the punishinent of rioters and those who are guilty of such assemblies, congregations, covins or insurrections, this grant is to remain in force without revocation. By signet letter.

Kings Wessex: Great x 10 Grand Son of King Edmund "Ironside" I of England

Kings England: Great x 2 Grand Son of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Kings Scotland: Great x 8 Grand Son of Malcolm III King Scotland

Kings Franks: Great x 6 Grand Son of Louis VII King Franks

Kings France: Great x 7 Grand Son of Louis "Fat" VI King France

Anne Neville Queen Consort England x 1

Queen Anne Boleyn of England x 1

Catherine Parr Queen Consort England x 1

Jane "Nine Days Queen" Grey I Queen England and Ireland x 1

Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom x 42

Great x 3 Grandfather: William Montagu

Great x 2 Grandfather: Simon Montagu 1st Baron Montagu

Great x 1 Grandfather: William Montagu 2nd Baron Montagu

Great x 2 Grandmother: Hawise St Amand

GrandFather: William Montagu 1st Earl Salisbury

Great x 4 Grandfather: Thurstan Montfort

Great x 3 Grandfather: Peter Montfort

Great x 4 Grandmother: Mabel Cantilupe

Great x 2 Grandfather: Peter Montfort

Great x 4 Grandfather: Henry Audley

Great x 3 Grandmother: Alice Audley

Great x 4 Grandmother: Bertrade Mainwaring

Great x 1 Grandmother: Elizabeth Montfort Baroness Furnivall Baroness Montagu

Father: John Montagu 1st Baron Montagu, Baron Monthermer

Great x 2 Grandfather: Pierre Grandison

Great x 1 Grandfather: William Grandison 1st Baron Grandison

GrandMother: Catherine Grandison Countess of Salisbury

Great x 1 Grandmother: Sibylla Tregoz Baroness Grandison

John Montagu 3rd Earl Salisbury  2 x Great Grand Son of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

2 x Great Grand Son of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Great x 1 Grandfather: Ralph Monthermer 1st Baron Monthermer

GrandFather: Thomas Monthermer 2nd Baron Monthermer  Grand Son of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Grand Son of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Great x 4 Grandfather: King John "Lackland" of England Son of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Son of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Great x 3 Grandfather: King Henry III of England Son of King John "Lackland" of England

Son of King John "Lackland" of England

Great x 4 Grandmother: Isabella of Angoulême Queen Consort England

Great x 2 Grandfather: King Edward "Longshanks" I of England Son of King Henry III of England

Son of King Henry III of England

Great x 4 Grandfather: Raymond Berenguer Provence IV Count Provence

Great x 3 Grandmother: Eleanor of Provence Queen Consort England

Great x 4 Grandmother: Beatrice Savoy Countess Provence

Great x 1 Grandmother: Joan of Acre Countess Gloucester and Hertford  Daughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Daughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Great x 4 Grandfather: Alfonso IX King Leon

Great x 3 Grandfather: Ferdinand III King Castile III King Leon Great Grand Son of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Great Grand Son of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Great x 4 Grandmother: Berengaria Ivrea I Queen Castile Grand Daughter of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Grand Daughter of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Great x 2 Grandmother: Eleanor of Castile Queen Consort England 2 x Great Grand Daughter of King Henry "Curtmantle" II of England

Great x 4 Grandfather: Simon Dammartin

Great x 3 Grandmother: Joan Dammartin Queen Consort Castile and Leon

Great x 4 Grandmother: Marie Montgomery Countess Ponthieu

Mother: Margaret Monthermer Baroness Montagu 3rd Baroness Monthermer  Great Grand Daughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Great Grand Daughter of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England

Great x 1 Grandfather: Peter Brewes Count Flanders

GrandMother: Margaret Brewes Baroness Monthermer