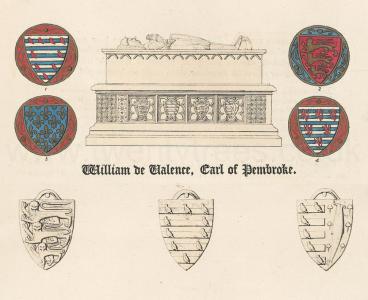

Effigy of William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke

Effigy of William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke is in Monumental Effigies of Great Britain.

WILLIAM DE VALENCE, son of Hugh de Brun, Earl of March, and half-brother by his mother, Isabel d'Angouleme, to Henry III, in 1247, came to England. Soon after his arrival he was with great state and solemnity knighted by the king at Westminster, who continuing to lavish favours on him and his brothers, and also giving himself too much to their counsels, the indignation and hatred of the barons was raised against them. In consequence William de Valence was obliged to quit the kingdom, but returning three or four years after, commanded in the king's army at the battle of Lewes, 1264. On seeing the day lost he fled to Pevensey, and from thence to France; but it appears he did not remain there any time, being at the battle of Evesham, 1265, which restored to Henry III. his regal authority. William de Valence, 10th of Edward I, 1283, was in the expedition against the Welsh, and in 1296 being at Bayonne, was there slain by the French.

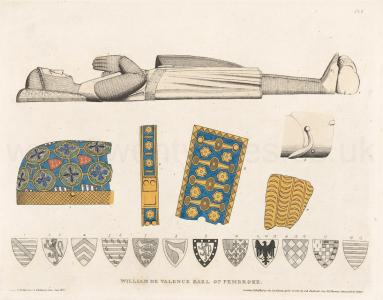

His monument is composed of an altar tomb of stone, on which is raised a superstructure of oak, bearing the effigy of the deceased, formed of the same material: the whole of this wood-work was once covered with plates of copper enamelled and gilt; but of these splendid decorations, there is scarcely any thing left but what is to be found on the figure, which has also suffered in parts. The human form is rudely expressed, a costly display of materials and workmanship appears to have been the principal object of the artist who executed it; and it indeed gives a very high idea of the goldsmith's art at that early period. William de Valence is represented entirely in mail. On his head is a rich circle, once adorned with stones or glass, but the empty collets now only remain. The surcoat has been powdered with a number of little escutcheons bearing the arms of De Valence, only three of these are left; the situation and number of those gone may be easily traced. The rich lacing about the surcoat and arms, appears to have been used for the purpose of concealing the unsightly joinings of the plates which cover the figure. In the spurs it is remarkable that they have been fastened on with cloth, in form of straps of an extraordinary thickness; of these, as might be expected, but a small portion remains. The table of the tomb has been covered with a fret of the arms of England and De Valence; it is possible that on the raised border which surrounded it, was the inscription, perfect in Weever's time, who says, "about the verge or side of his monument these verses are inlayed with brasse."

Anglia tota doles, moritur quia regia proles. [The whole kingdom is suffering, it is dying because you are a royal child.]

Qua Horere soles, quem continet intima moles, [With which you are accustomed to fear, which the innermost mass contains,]

Guilielmus nomen insigne Valentia prsebet [The distinguished name of William still lives in Valentia]

Celsum cognomen, nam tale dari sibi debet [A lofty surname, for such should be given to him]

Qui valuit validus, vincens virtute valore, [He who prevailed strong, conquering by valor by valor,]

Et placuit placidus, sensus morumque vigore, [And he was pleased with the calm, with the strength of his senses and manners,]

Dapsilis et habilis, immotus, praelia sectans [Plentiful and dexterous, motionless, following the battles]

Utilis ac humilis, devotus praemia spectans [Helpful and humble, devoted looking for rewards]

Milleque trecentis cum quatuor inde retentis. [One thousand three hundred and four were retained]

In Maii mense, hanc mors propria ferit ense, [In the month of May, death strikes with her own sword]

Quique legis haec repete quam sit via plena timore, [And let him who reads these things repeat what a way is full of fear]

Meque lege, te moriturum & inscius hore, [Read with me, you will die and be unconscious]

O clemens christe celos intret precor iste. [O merciful Christ, I pray that he may enter into heaven]

Nil videat triste, quia pretulit omnibus hisce. [Let him see nothing sad, because he preferred all these things.]

On the sides and ends of this part of the tomb, are the remains of arches, twelve on each side, three at top, and four at bottom, within which were probably figures representing the relatives of the deceased; for at the foot of each arch, placed horizontally, formerly was an escutcheon to point out each personage; five only are now left, given in the margin, fig. 1, 2, 3, 4. No. 2 is repeated. In one of the Lansdowne MSS. in the British Museum, are drawings, taken in 1610, of nineteen of the lost escutcheons. As they cannot be more in place than here, they are given, plate 2,—where there are repetitions, they are marked by the figures. The stone altar tomb, on which the parts described are raised, has on its sides and foot, on escutcheons in relief the arms of England, William de Valence, and Aymer his son. The latter are distinguished by being dimidiated with those of Clermonta. There is good ground for supposing the upper or metallic part of the tomb to be French work. The mode of bearing the shield on the hip, and of emblazoning the surcoat by little escutcheons, are both fashions common to French monuments, seldom if ever occurring in this country. That we did employ French artists in enamelled tombs, there is proof in that of Walter de Merton, executed at Limoges, and put up in Rochester Cathedral, but destroyed at the Reformationb. That the style of the tomb in question was otherwise French than in the points abovementioned, we may see by comparing it with Lobineau's print of the enamelled tomb of Alice, Duchess de Bretagne.

Details—Plate 1, Fig. 1. The circle enlarged:—2, 3, and 4, portions of the lacing on the surcoat. The enamelling and diapering on the shield. And of the enamelled Ret. 5. The remains of the sword. 6. Engraved border on the lower part of the surcoat. Plate 2, Fig. 1, 2, and 3. Enamelling on the pillow and beltsc. 4. Portion of the mail, formed by engraved lines, and appears to be of that kind which is so seldom represented on stone. 5. Spur, with part of the strap.

Note a. Beatrice, daughter of Raoul de Clermont, Lord of Nesle, Constable of France, was the first wife of Aymer de Valence, and was probably living at the time the tomb was erected.

Note b. This tomb, which was of copper enamelled and gilt, cost for its construction, and the expense of its carriage from Limoges to Rochester, £41. 5s. 6d.

Note c. Neither of the belts have any arms emblazoned on them, nor are the escutcheons on the surcoat, but six in number.—Vide

Archaeologia Volume 21 Section XXXII. The care and attention with which the sculptor carved the attendants upon this Effigy, induces me to believe them to be the figures of her children; for they are much larger than those upon other monuments of its own time, before or since. Those of other monumental effigies are represented supporting the crest, as in Aymer de Valence’s; burning incense, as in John’s; and generally, as in these, they are represented with wings, as angels; but those in the Effigy at Stevenage bear evident marks of uncommon attention being paid to distinguish them from others. And I am induced to believe also, that the one on the left with the cowl, represents John de Stevenage, a cellarer of St. Alban’s Monastery, from the 27th to the 31st of Edward the First, 1298 to 1302, a descendant of the original founder of the Abbey of Stevenage. The Village of Stevenage derived its name from a monastery which formerly stood near or on the site of the present church, about half a mile from the road. Chauncy says, the Abbot of Stevenage held it of the gift of Edward the Confessor, and claimed very large liberties by the grants of the said King, and the grants of William the Conqueror, Henry the First, and Richard the First, which upon a quo warranto therein allowed,a and the Abbot thereof did continually enjoy it until the dissolution of the great Monasteries.