The Reliquary Volume 20 81-85 Arbor Low

The Reliquary Volume 20 81-85 Arbor Low is in The Reliquary Volume 20 1879.

Arbor Low [Map]1 By Sir John Lubbock (age 44), Bart., M.P., F.R.S., F.S.A.

Note 1. I have to express my profound indebtedness to Sir John Lubbock, for permitting the "Reliquary" to be the medium of giving to the antiquarian world this important paper, read by him, on the spot-at Arbor Low itself-before the Members of the British Association, on the 23rd of August, in the present autumn. Sir John in the hand, placed his MS. in my hands for publication, and I feel that by so doing he has not only conferred a favour on myself, but a great boon on all of archæology. L. JEWITT (age 62).

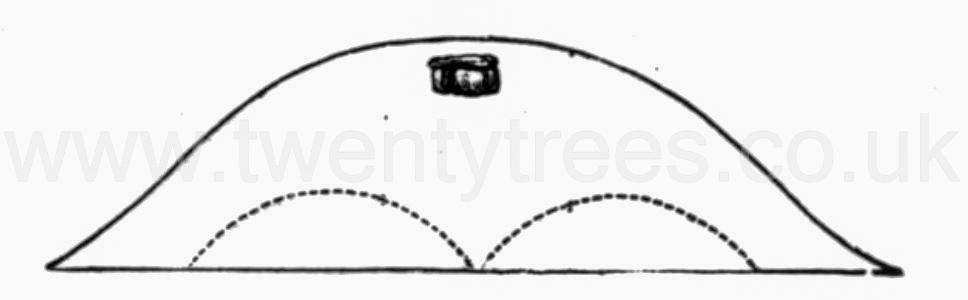

The celebrated Temple of Arbor Low, the most important monument of the kind in this part of England, consists of a circle of large, unhewn limestones surrounded by a deep ditch, outside of which rises a lofty vallum. The stones composing the circle are rough, unhewn masses, about thirty or forty in number; though as several are broken, this cannot exactly be determined; they are from six to eight feet in length, by about three or four feet in breadth at the widest part. At present they are all lying on the ground, and it is doubtful whether they were ever upright. Within the circle are some smaller scattered stones, and in the centre are three larger ones, which may, perhaps, have originally formed a dolmen, or sepulchral chamber. The central platform is 167 feet in diameter. The width of the fosse is about 18 feet; the height of the bank or vallum on the inside (though much reduced by the unsparing hand of Time), is still from 18 to 24 feet. The vallum is chiefly formed of the earth thrown out of the ditch, with a little from the ground which immediately surrounds the exterior of the vallum; thus adding to its height, and to the imposing appearance it presents to any one approaching from a distance. To the enclosed area are two entrances, each of the width of ten or twelve yards, and opening towards the north and south. On the east side of the southern entrance is a large barrow [Map], holding, in the opinion of some archaeologists, the same relation to the circle as Long Meg [Map] to the circle of stones [Map] near Penrith, known as her "daughters." This mound was first attacked in 1770, by the then occupier of the farm; secondly, in 1782, by Major Rooke; and thirdly, in 1824, by Mr. William Bateman; but none of these gentlemen succeeded in discovering the interment. At length, in 1845, Mr. Thomas Bateman was more fortunate.

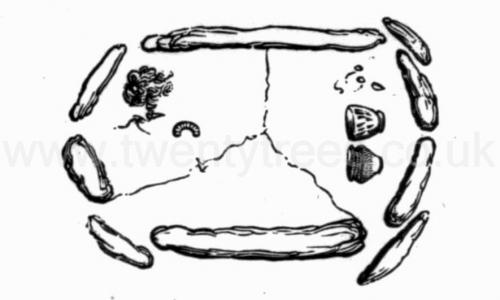

He commenced by cutting a trench across the barrow [Map] from the south side. In the operation a shoulder-blade and antler of red deer were discovered, and also a number of water-rats' bones. On reaching the highest part of the tumulus, which was elevated about four yards above the natural soil, a large flat stone was discovered, about five feet in length, by three feet in width, lying in a horizontal position, about eighteen inches above the natural floor. This stone was cleared, when a small six-sided cist was exposed, constructed of ten limestone blocks, which were placed on one end, and having a floor of three similar stones. The chamber was quite free from soil, the cover having prevented the entrance of earth, and protected the contents, which were a quantity of calcined human bones, strewed about the floor of the cist; amongst which were found a rude kidney-shaped instrument of flint, a pin made from the leg-bone of a small deer, and a piece of spherical iron pyrites. At the west end of the cist were two ornamented, but dissimilar, urns of coarse clay. One had fallen to pieces, but has since been restored, and is of an elegant form; the other was taken out quite perfect, and is of much ruder design and workmanship. In addition to these urns, a piece of the ornamented upper edge of another vase, quite unlike the others, was found, The floor of the chamber was laid - the natural soil, and the cist was strewed with rats' bones, both within and without. The pin had probably been used as a brooch, while the flint and iron pyrites, which have been found in association in other barrows, probably served for procuring fire. The urns belong to the type which have been called food vessels, to distinguish them from the cinerary urns in which the ashes of the deceased were placed. They may have contained two sorts of food, or food and drink; or, as Mr. Bateman supposes, the presence of two may indicate a double burial.

About a quarter of a mile to the west, there is a large conical tumulus, known as Gib Hill [Map], which was connected with Arbor Low by a rampart of earth, which, however, is now very faint and imperfect. Gib Hill was opened: by Mr. Bateman in 1848. He found that it had been raised over four smaller mounds, consisting of hardened clay mixed with wood and charcoal. The central interment consisted of a dolmen, or stone chamber, situated near the top of the mound. It was composed of four massive limestone blocks covered by a fifth, about four feet square by ten inches in thickness. The cist, having fallen in, was removed, and re-erected in the garden at Lomberdale House [Map]. It contained only a small urn, four-and-a-quarter inches in height, a piece of white flint, and burnt human bones. In the earth of the tumulus were found also a flint arrow-head, a fragment of a basaltic celt, a small iron brooch, and another fragment of iron, supposed by Mr. Bateman to have belonged to a later interment, which had been previously disturbed. To the west, is the Roman Road from Buxton, which passes southwards, not far from Kenslow Top [Map] to the great tumulus of Minning Low [Map].

The name, Arbor Low, is not without interest. The termination, Low, of course is not part of the name, but is equivalent to "tumulus," "barrow," or "hill," for among our Saxon ancestors "down" meant "up," and "low" meant "high," coming from "lifian," whence our verb to "lift." "Arbor," or "Arbe," as it is variously pronounced, is evidently the same word as "Abury [Map]," the great sanctum of our country; the greatest megalithic monument indeed in the world.

There can be no doubt that Gib Hill [Map], and the tumulus here, were places of burial; but the original purpose of the circle is not so obvious. Mr. Bateman called it a temple; but the temple is the House of the Deity, and even when perfect this can scarcely have been regarded as a house. Still, just as the tomb was the house of the dead, sometimes a copy of the dwelling, nay, in some cases the very dwelling itself of the deceased, so by an obvious chain of ideas the tomb developed into the temple. Now we may regard a perfect megalithic interment as having consisted of a stone chamber, communicating with the outside by a passage, covered with a mound of earth, surrounded and supported at the circumference by a circle of stones,.and in some cases surmounted by a stone pillar or "menhir."

Sometimes, however, we find the central chamber standing alone, as at Kits Coty House [Map], near Maidstone, which may or may not have ever been covered by a mound; sometimes, especially of course where stone was scarce, we find the earthen mound alone; sometimes only the menhir; the celebrated stone avenues of Carnac, in Brittany, and the stone rows of Abury, may, I think, have been highly developed specimens of the entrance passage; in Stonehenge, and many other instances, we have the stone circle. In fact, these different parts of the perfect monument are found in every combination and in every degree of development, from the slight elevation scarcely perceptible to the eye-excepting perhaps when it is thrown into relief by the slanting rays of the setting sun-to the gigantic hill of Silbury [Map]; from the small stone circle, to the stupendous monuments of Stonehenge or Abury.

Even now, the northern races of men live in houses formed on the model of these tombs. Having to contend with an Arctic climate, they construct a subterranean chamber, over which they pile earth for the sake of warmth; and which, for the same reason, communicates with the open air, not directly, but by means of a long passage.

In some cases, tumuli, exactly resembling these modern houses, have been discovered. At Godhavn, for instance, in Sweden, such a grave was opened in 1830, and the dead were found sitting round, each with his implements, in the very seats which doubtless they had occupied when alive. Thus then, in some cases, that which was at first a house at length became a tomb.

So again, the tomb in the same way becomes a temple. The Khasias are primitive people of India, who even now construct megalithic monuments over the dead. They then proceed to offer food and drink to the deceased, and to implore their assistance; if after praying at a particular tomb they obtain their desires, they return again, and if success is repeated, this tomb gradually acquires a certain reputation, and the person buried in it becomes more or less of a deity. When a considerable celebrity had thus been acquired, other shrines would naturally be consecrated to him by those anxious for his assistance, and these would be constructed on the model of the first. No wonder then that it is impossible to distinguish the tomb from the temple.

Now the natural question will arise, when was this monument erected? and I can but give the simple answer - I do not know. Only last week I was opening a barrow in Wiltshire with one of our best archeologists, Mr. Cunnington; he was asked the same question. "I do not know," he said, "nobody does know, and nobody ever will know." I should not like to go so far as that. Why should we despair? When Bruce asked his negro guide what became of the sun at night, the man said that it was no use troubling ourselves about questions which were beyond the range of the human intellect. More recently, Comte laid it down as an axiom, that we could ascertain nothing about the heavenly bodies excepting their mass and movements, yet he was scarcely dead before we had analysed the very stars. I fully hope then that one day this question also may be answered. But if we cannot reply in terms of years, still some answer I think may be given.

Archæologists have divided the period of the human occupation of this country into five great epochs. Commencing with the earliest, in which there are any conclusive traces of man, in the Palæolithic, or Early Stone Age, the climate was very severe, and our country was inhabited by a race of men coeval with the mammoth and woolly-haired rhinoceros, the hippopotamus, the musk ox and reindeer, the white bear and Irish elk. Our predecessors, at that period, used stone implements, rudely chipped, but not ground. In the Second Stone or Neolithic period, the extinct animals had already disappeared. The climate had improved. Man had learnt to polish his stone implements, he made rude pottery, and had even some knowledge of agriculture, though still probably depending for the most part on the produce of the chase. In the third or Bronze Age, he had still further advanced, and had become acquainted with the use of bronze, a combination of copper and tin, the knowledge of which was probably introduced from the East. Fourthly came the Iron Age, during which the use of iron gradually superseded that of bronze for cutting purposes. Lastly, came the historic period, commencing in this country with the advent of the Romans.

None of our tumuli can be ascribed to the Palæolithic period, but there can be no doubt that many of them belong to the Neolithic Age; some, on the other hand, are certainly Saxon; but from the character of the remains found in them, I am disposed to refer those which cluster round Stonehenge or Abury, and consequently the monument on which we now stand, to the Bronze Age.

It is impossible to let the mind dwell on these distant periods, it is impossible to view a pre-historic monument like the present, either the last resting-place of some one who was once evidently either greatly loved or feared, or perhaps the locality of some great event, without attempting to picture to oneself what we might then have witnessed, to realise the scene which would then have presented itself. To attempt to bring it before you, however, would require the sacred fire of the poet. I feel myself unequal to such a task.

Let me, however, before I close, make an earnest appeal to you in the name of the dead. In the eloquent words of Ruskin, with which I will conclude, "The dead still have their right in them [these monuments]; that which they laboured for, the praise of achievement, or the expression of religious feeling, or whatsoever else it might be which they intended to be permanent, we have no right to obliterate. What we have ourselves built we are at liberty to throw down; but what other men gave their strength and wealth and life to accomplish, their right over does not pass away with their death; still less is the right to the use of what they have left vested inus only. It belongs to all their successors." Our children will justly blame us if we lightly sacrifice these precious heir-looms which we have received from those who have gone before us.

Harold Gray 1902. Dr. Pegge, writing in 17831, says that "the stones formerly stood on end, two and two together, which is very particular." Glover, in his History of the County of Derby (1829), states that "Mr. J. Pilkington was informed that a very old man living in Middleton, remembered when a boy to have seen them standing obliquely upon one end"; tersely adding that "this secondary kind of evidence does not seem entitled to much credit." One of my excavators, an old man, assured me that he had seen five stones standing in his boyhood, and had sheltered under them! On inquiry, however, I ascertained that the man had a reputation for gross exaggeration. The Rev. S. Isaacson, writing in 1845, was of opinion that "these stones were never placed in an erect position." He says further that "the imported stones all appear to be resting on the native rock, the comparatively thin covering of soil having accumulated through the lapse of centuries." Gardner Wilkinson, on the other hand, in 1860, says "it is evident that they originally stood upright, as in other sacred circles." Lord Avebury, writing some twenty-five years ago, stated cautiously, "It is doubtful whether they were ever upright."2 As recently as 1899, Dr. Brushfield appeared to be of opinion that the stones originally stood upright; and Mr. A. L. Lewis is of the same opinion3.

Note 1. Archeologia, vii., r4z

Note 2. The Reliquary, xx. 81-85, with view and woodcuts.

Note 3. Man. (Anthropological Institute), September, 1903, No. 76.