Wessex from the Air Plate 36

Wessex from the Air Plate 36 is in Wessex from the Air.

Reference No. 117. Height above Sea-level. Between 500 and 530 ft. (152 and 161 metres). County. Wilts. 28 NW. and SW. (112: D. 5). Parish. Avebury. Geological Formation, Middle Chalk, Latitude. 51° 25' 40" N Longitude. 1° 51' 12" W. (cross-roads near centre of the Great Circle) Time and Date of Photograph. 9.7 a.m., 22nd June [1928]. Height of Aeroplane. 5,400 ft. (1,645 metres). Speed of Shutter. 1/180th of a second.

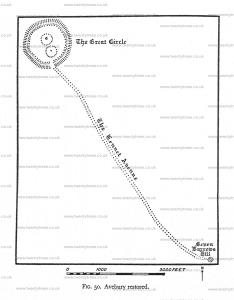

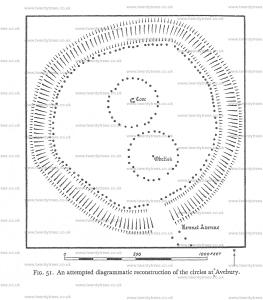

Avebury consists of a Great Circle of huge stones, originally about a hundred in number, standing on the inner rim of an encircling ditch. On the outer side of the ditch is a bank which originally towered no less than 55 ft. above the bottom of the ditch. On the circular plateau thus enclosed were two smaller stone-circles; in the centre of the northern circle are still two huge uprights called by Stukeley ‘The Cove [Map]’ (17 ft. and 14 ft. 7 in. high respectively); in the centre of the southern was a single stone [Avebury South Circle Obelisk [Map]], but it may only have been the last survivor of a structure hke the Cove, which latter originally consisted of three stones. The diameter of the Great Circle is about 1,130 ft. and of the inner circles about 340 ft.

From a gap in the ditch on the south side starts the Kennet Avenue — a stone avenue of about 200 stones; it is i mile 800 yds. long, and about 40 ft. wide. At the present time only 21 out of the 200 avenue-stones are in existence. Of these, 7 are still standing; of the remaining 14, all except one are visible. By far the best existing section of the avenue is a group of 1 1 stones in a grass field on the right or south-western side of the Marlborough Road, half a mile out of Avebury village. The last 5 of those now remaining are those in the bank on the south side of the Bath Road, immediately east of West Kennet. They lie in the field side of the bank, and cannot be seen from the road.

The Avebury Avenue consisted of standing stones, and differed, therefore, from the Stonehenge Avenue, which consisted of a ditch and bank. It is also considerably narrower than the Stonehenge Avenue. Like it, however, the Avebury Avenue does not take a straight course, though the deviation from a straight line is nowhere more than 140 yds. It ends on Overton Hill (also called Seven Barrows Hill), where formerly stood two much smaller concentric stone circles. In the eighteenth century the stones of the avenue were visible right up to these circles, but now neither avenue nor circles remain. For whatever purpose these avenues were made, it was quite certainly not an astronomical one.

Avebury was discovered by Aubrey in 1648 or 1649; but it is to 'ingenious Stukeley’ that we owe most of our knowledge about it, for since his days a great deal of destruction has been carried out. Had not Stukeley had the gout, he would not have ‘ridden on horse-back in the spring for the recovery of his health' and while so doing ‘indulged his natural love of antiquitys ’. Stukeley might have been happier, but the world would have been poorer; for his monumental work on Avebury is still the only reputable book that has been written about the greatest prehistoric monument of Britain; and it could not be written to-day, for much that it records is gone for ever. He may have been fanciful and absurd in his conjectures, but he was diligent and generally accurate in his record of facts. Judged by the standard of his times he deserves to be recognized as a good archaeologist and the pioneer of field-work. Unfortunately, he was bitten by a theory; he believed that Avebury was designed in the plan of a snake, the head being the circles on Overton Hill and the avenue part of the body. To complete the picture he imagined another avenue leading south-westwards out of the Great Circle towards Beckhampton; and he has left two plans showing the disposition of the stones in both avenues.

His plan of the Kennet Avenue is a priceless document, which was recently disinterred by the writer of this account. Tested by existing remains it is found to be entirely reliable, and indeed it bears internal evidence of accuracy. It records the existence of 84 stones, all of them visible in 1723 when it was made (except 2 which were buried). Of these 84 no less than 21 were still standing. In the two hundred years which have since elapsed, 63 of these stones have disappeared, mostly during the first half of this period. To-day, as has been said, only 21 are in existence, and only 7 still standing. Let us once for all pay a tribute of esteem and gratitude to Stukeley’s memory.

But it is less easy to deal with the still unsolved problem of the Beckhampton Avenue. The evidence for its existence rests solely on the authority of Stukeley, and on the two stones still standing in a large field between Beckhampton and Avebury (Plate XXXVIII, 1 and 2, near top left-hand corner). Unfortunately, Stukeley’s two recently discovered plans of the Beckhampton Avenue do not agree: they make it follow different courses. (It is difficult to locate the positions of the stones from these plans, because the field-boundaries have been altered since then; but there seems no doubt that the two plans are inconsistent.)

It was in order to see whether air-photography would help to clear up the matter that these photographs were taken. Unfortunately, they leave it where it was. There are no signs on any of them of stone-holes. They are, however, reproduced here since even negative evidence may be.valuaable. It does not, of course, follow that, if the Beckhampton Avenue did exist, traces of It might not be visible under different conditions of soil and crops.

Finally, a word must be said about the age and purpose of Avebury as a whole.

The British Association excavations conducted between 1908 and 1914 by Mr. St. George Gray suggest, according to the excavator, that it was built during the same period as the West Kennet long barrow. This is usually attributed to the end of the neolithic period— nearly everything seems to belong to the end of that mysterious age!— but I should hesitate to deny the possibility that a few rare implements of copper might not have been in use, though there is no evidence for them. The builders probably lived on Windmill Hill, a mile to the north-west, where an earthwork of unusual character is now being excavated by Mr. and Mi's. Keiller, and is yielding much neolithic pottery.

The purpose was probably sepulchral. We may imagine that the Cove originally contained an interment — its arrangement when perfect recalls the burial-chambers of Brittany and Cornwall; and a similar cove probably occupied the now empty place of the obelisk, at the centre of the southern circle. So, too, the Altar-stone in the centre of Stonehenge may be the fallen survivor of a ‘cove’; and, whether that be so or no, Stonehenge, too, was doubtless a large tomb. In making these assertions, for the benefit of my readers, I am stating a personal opinion of a speculative kind, and am not passing on the assured and agreed conclusions of archaeologists. The archaeologist, however, forms his opinion in such cases by reasoning from analogy. Both Avebury and Stonehenge are stone circles; and all those stone circles elsewhere which have been properly excavated have yielded evidence proving their peculiarly sepulchral character.

It does not, however, follow that, in those early days when social functions were less specialized— less ‘canalized’ — the tomb of a great man or woman may not have been the scene of great gatherings, of primitive folk-moots and parliaments. If Avebury was sepulchral it is probable that each of the two inner circles contained a burial. To compare great things with small, the plan of Avebury resembles, in stone, the plan of those disc-barrows with two burial-mounds in them (see Plate XXXI). This resemblance was suggested to me by Professor Menghin, on Oakley Down. Moreover, disc-barrows are supposed to be the burial-places of women (Arch, xliii), and women held an important place in the social hierarchy of the Bronze Age, if we may trust the historical descriptions of Pictish customs and the oldest traditions of Ireland. Whether Avebury may be a big disc-barrow or disc-barrows be little Aveburys one cannot say; but the resemblance may not be entirely without significance.

O.G.S.G. (age 41)

Literary References

John Aubrey, Mon. Brit. (Bodleian Library, Oxford); plan of Avebury made 1663; reproduced in facsimile in W.A.M., vol. vii.

Willaim Stukeley, Abury, a temple of the British Druids, 1743.

William Long, ‘Abury Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine, vol. iv (January 1858), pp. 309-63. (This is by far thebest existing account of Avebury.)

Facsimiles of Aubrey’s plans of Avebury, and corrigenda of preceding paper; W.A.M. vii (December 1861) ,pp, 224—6.

The Rev, A, C. Smith, 'Excavations at Avebury W,A.M, x (January 1867), pp. 209-16. (An account of excavations made there by Mr. Smith, associated with Messrs. W. G. Lukis, W. Cunnington, and King, 29th September to 5th October 1865. Excavations were made in the Northern Inner Circle, near and also within the Cove itself, in the mound or embankment to the south-east, in the Southern Circle, and through the Great Outer Bank.)

William Long, 'Abury Notes’, W.A.M. xvii (March 1878), pp. 327-35. (Valuable notes on lost, buried, or destroyed stones in the circles and avenues, especially the Kennet Avenue.)

The Rev. Bryan King, Vicar of Avebury, ‘Avebury— The Beckhampton Avenue’, W.A.M. xviii (November 1879), pp. 377-83. (A vigorous defence of the Beckhampton Avenue, supported by evidence.)

‘A buried stone in the Kennet Avenue’, W.A.M. xxxviii (June 1913), pp. 12—14.

H. St. George Gray, Reports on Excavations at Avebury; published in the Reports of the British Association for the years 1908 (401-11), 1909 (271-84), 1911 (141-52), 1915 (174-89), 1922 (326-33).