Whetstone

Whetstone is in Prehistoric Artefacts.

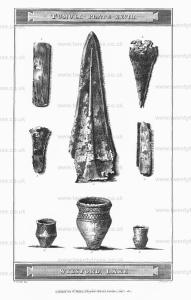

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 8 [Map] is a very wide and flat barrow, elevated about six feet from the ground, and supposed to be the one from which the French Prophets1, about the year 1710, delivered their doctrines, as its summit presents an even surface of 48 feet in diameter. To ensure success in a mound of such magnitude, we were obliged to make a very large section, in which, at the depth of two feet, we came to the top of a pile of marl, which encreased in size as we approached the floor. After considerable labour we found, on the north side of our section, the cist from whence this marl had been thrown out; it was eight feet and a half long, and above two feet wide, and contained a pile of burned human bones, which bad been enclosed within a box of wood. Near the bones lay a fine spear-head, [Plate XXVIII. No. 7.] and a whetstone. From the singular form and extraordinary size of this barrow, we expected to have made more important discoveries; and though most probably we found the primary deposit in the centre or place of honour, it is not at all unlikely that the sides of this large mound might produce other sepulchral deposits.

Note 1. Dr. Stukeley says, that the country people call this group the Prophet's barrows, because the French prophets, 30 years ago (A. D. 1710 set up a standard on the largest barrow, and preached to the enthusiastic multitude." Among the multitude of protestants who fled from France in consequence of the horrible persecutions which followed the revocation OF the Edict of Nantz, were same enthusiasts, who pretended to the gift of prophecy, and other spiritual gifts. These enthusiasts travelled over various parts of the kingdom preaching ta the people, and according to tradition, the summit of one of these barrows was chosen as a fit place for the prophet's oration.

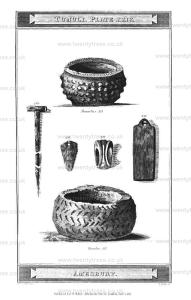

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 18 [Map]. This large bell-shaped barrow, 121 feet in diameter, and 11 in elevation, may be considered as the monarch of this group, both as to its size, as well as contents. On the floor of the barrow we found the skeleton of a very tall and stout man, lying on his right side, with his head towards the south-east. At his feet were laid a massive hammer of a dark coloured stone. A brass celt, a tube of bone, a handle to some instrument of the same, a whetstone with a groove in the centre, and several other articles of bone, amongst which is the enormous tusk of a wild boar; but amongst these numerous relicks, the most curious article is one of twisted brass, whose ancient use, I leave to my learned brother antiquaries to ascertain. It is unlike any thing we have ever yet discovered, and was evidently fixed into a handle as may be seen by the three holes, and one of the pins still remaining: the rings seem to have been annexed to it for the purpose of suspension. This article, together with the celt and boar's tusk form a very interesting engraving, and are all drawn of the same size as the originals in Tumuli Plate XXIX.

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 139 [Map], a mean barrow, composed entirely of vegetable earth, produced within a shallow cist a pile of burned bones, and with them two fine daggers of brass, a long pin of the same metal in the form of a crutch, a whetstone, and a small pipe of bone. This last article is now broken, but it was originally about seven or eight inches long, and more than a quarter of an inch in diameter at the small, and half an inch at the large end; it is thin, and neatly polished, and has a perforation near the centre. The brass pin and whetstone are engraved in Tumuli Plate XXIV.

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 8 [Map]. This barrow, rather inclined to the bell shape, is 82 feet in diameter, and in elevation. It contained within a shallow oblong cist, the burned bones (as we conceived) of two persons piled together, but without arms or trinkets. In excavating the earth from this barrow, our men found a piece of square stone polished on one side, having two marks cut into it, also a whetstone.

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 25 [Map] is a large and rude bowl-shaped barrow, 107 feet in diameter, and 6 in elevation. Its surface being uneven, we were led to suppose it had been opened. In making a large section into it, the workmen threw out the bones of several dogs, and some of deer, and on the floor found a human skeleton, which had been originally interred from north to south, but many of the bones had been displaced, probably owing to a recent interment of burned bones, which had been deposited near the feet of this skeleton. On the right side of its head were two small earthen cups, one of which was broken; the other preserved entire; the first, though of rude materials, and scarcely half burned, was very neatly ornamented; the other, is of a singular form and pattern: it is of a yellowish colour, and perforated in several places. Near these, cups was a curious ring or bracelet of bone or ivory, stained with red, which was unfortunately broken into several pieces. With the above articles were two oblong beads made from bone, and two whetstones; one of the silicious kind, almost as fine as a hone, and neatly formed; the other, of a fine grained white silicious stone. Near the above were brass pin, a pair of petrified fossil cockle shells, a piece of stalactite, and a hard fiat stone of the pebble kind, such as we frequently find both in the towns; as well as in the tumuli of the Britons.

Colt Hoare 1812. On the opposite hill is a beautiful group of tumuli, thickly strewed over a rich and verdant down. Their perfect appearance raised our expectations of success, and the attendance of many of my friends from Salisbury, and a beautiful day, enlivened our prospects; but we had again sad cause to exclaim Fronti nullaa fides, Trust not to outward appearances. No arrow heads were found to mark the profession of the British hunter; no gilded dagger to point out to us the chieftain of the clan; nor any necklace of amber or jet, to distinguish the British female, or to present to her fair descendants, who honoured us with their presence on this occasion: a few rude urns marked the antiquity and poverty of the Britons who fixed on this spot as their mausoleum, Unproductive, however, as were the contents of these barrows, it may not be uninteresting to the antiquary, whom either chance or curiosity leads across these fine plains, to know their history.

Note 1. On referring to Mr. CUNNINGTON'S papers, find some account of these barrows. The Druid barrows had been partially opened: in one, he found an interment, with a broken dart or lance of brass; and in another, the scattered fragments or burned bones, a Few small amber rings, beads of the same, and of jet, with the point of a brass dart. In opening the large barrow, No. 57 [Map] he found a cist, at the depth twelve feet from the surface, the remainder (as he thought) of the brass dart, and with it a curious whetstone, some ivory tweezers, and some decayed articles of bone.

Colt Hoare 1812. Yet I do not wish you to suppose that all these antiquities can boast the same remote æra of antiquity; for in them we may clearly distinguish the marks of two distinct people, the Britons, and their conquerors, the Romans. To the first I would attribute the construction of Stonehenge, and the raising of the barrows; to the latter, the cursus1, and the principal remains of the villages; for although we find in them fragments of rude unbaked pottery, yet the well the villages also on Stoke down burned Roman earthen ware preponderates: bear rather a more regular form in their plan, than we usually meet within the original British settlements. That Stonehenge existed before some of the barrows adjoining it, has been clearly proved by the chippings of Stone discovered within them: and that: the custom of burying under tumuli ceased on our downs2 after the arrival of the Romans, is, I think, also proved, by our never having found a single urn either well baked, or turned with the lathe, in any one barrow. At the period when these villages were inhabited by a mixed population of Britons and Romans, whom I call Romanized Britons, they certainly had dropped the custom of burying under barrows, and having no index to direct our spades, we have never been fortunate in discovering the cemeteries of the people who inhabited these British villages.3 Such a discovery would be a grand and most satisfactory desideratum, for, instead of the rude and coarse urn of British pottery, we should then be gratified with specimens of that elegant earthen-ware for which the Romans (copying the Græcian models) were so justly cerebrated. That, even in the rudest times, other modes of burial, besides the barrow, were adopted, we have an interesting proof in an interment which was lately discovered above Durrington Walls, by a shepherd, who in pitching the fold, found his iron bar impeded in the ground: curiosity led him to explore the cause, which proved to be a large sarsen stone, covering the interment of a skeleton, with whose remains the articles were graved in Tumuli Plate XIX were deposited, viz. a spear head chipped from a flint, a small bone or whetstone, a cone and ring of jet like a pully, and two little buttons of marl or chalk, all bespeaking an interment of the earliest date.

Note 1. The cursus so resembles in form the Roman circus, that I am inclined to think its plan was introduced by that nation.

Note 2. When I say that the custom of burying under tumuli appeared to cease on tho mixture of the Romans with the Britons, allude only to own county: for Mr. Douglas, in his Nania Britannica, has clearly proved the same custom was continued in Kent later than the seventh century.

Note 3. If we refer on the map to the Situations of the numerous British villages already described, we shall find only a few scattered barrows around them, a proof that other modes of interment must have been adopted by the inhabitants of them.

Colt Hoare 1812. On the north-west side of this work are some barrows, one of which had been opened before, but in exploring it our men turned out the fragments of burned bones and a singular whetstone. Lower down on the south are some other in one of which, was found a brass dart or arrow head. To the east is a long barrow. About a mile, to the south or Robin Hood Ball, and on Knighton down, we find the undoubted remains of another small British settlement, consisting or a square earthen work. Its eastern side is bounded by a bank and ditch, which taking a southern direction, intersect a Druid barrow one hundred and thirty-two feet in diameter; another proof of the prior antiquity of the tumulus.

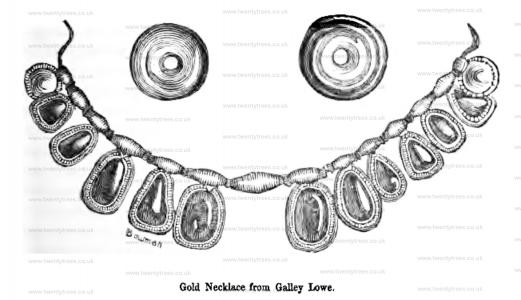

Section I Tumuli 1843. The 30th of June 1843 was occupied in examining the middle part of a large barrow on Brassington Moor, usually called Galley Lowe [Map], but formerly written Callidge Lowe, which is probably more correct. About two feet from the surface were found a few human bones mixed with rats' bones and horses' teeth; amongst these bones (which had been disturbed by a labourer digging in search of treasure) the following highly interesting and valuable articles were discovered: several pieces of iron, some in the form of rivets, others quite shapeless, having been broken on the occasion above referred to, two arrow-heads of the same metal, a piece of coarse sandstone, which was rubbed into the form of a whetstone; an ivory pin or bodkin, of very neat execution; the fragments of a large urn of well-baked earthenware, which was glazed in the interior for about an inch above the bottom; two beads, one of green glass, the other of white enamel, with a coil of blue running through it, and fourteen beautiful pendant ornaments of pure, gold, eleven of which are encircled by settings of large and brilliantly coloured garnets, two are of gold without setting, and the remaining one is of gold wire twisted in a spiral manner, from the centre towards each extremity (a gold loop of identical pattern is affixed to a barbaric copy of a gold coin of Honorius in the writer's possession); they have evidently been intended to form one ornament only, most probably a necklace, for which use their form peculiarly adapts them. It will here not be out of place to borrow some quotations relative to a remarkable superstition connected with glass beads similar to those discovered in Galley Lowe, particularly the one having "two circular lines of opaque sky-blue and white," which seem to represent a serpent entwined round a centre, which is perforated. "This was certainly one of the Glain Neidyr of the Britons, derived from glain, which is pure and holy, and neidyr, a snake. Under the word glain, Mr. Owen, in his Welsh Dictionary, has given the following article: "The Nair Glain, transparent stones, or adder stones, were worn by the different orders of the Bards, each exhibiting its appropriate colour. There is no certainty that they were worn from superstition originally; perhaps that was the circumstance which gave rise to it. Whatever might have been the cause, the notion of their rare virtues was universal in all places where the Bardic religion was taught."

These beads are thus noticed by Bishop Gibson, in his improved edition of Camden's Britannia: "In most parts of Wales, and throughout all Scotland, and in Cornwall, we find it a common opinion of the vulgar, that about Midsummer-eve (though in the time they do not all agree) it is usual for snakes to meet in companies, and that by joining heads together and hissing, a kind of bubble is formed, like a ring, about the head of one of them, which the rest, by continual hissing, blow on, until it comes off at the tail, when it immediately hardens, and resembles a glass ring, which whoever finds shall prosper in all his undertakings: the rings they supposed to be thus generated are called gleinen nadroeth, namely, gemma anguinum. They are small glass annulets, commonly about half as wide as our finger-rings, but much thicker, of a green colour usually, though some of them are blue, and others curiously waved with blue, red, and white.'' There seems to be some connexion between the glain neidyr of the Britons and the ovum anguinnm, mentioned by Pliny as being held in veneration by the Druids of Gaul and to the formation of which he gives nearly the same origin. They were probably worn as a mark of distinction, and suspended round the neck as the perforations are not large enough to admit the finger. A large portion of this barrow still remaining untouched on the south-east side, which was but little elevated above the natural soil, yet extending farther from the centre, it offered a larger area, in which interments were more likely to be found than any other part of the tumulus, it was decided on resuming the search on the 3d of July, 1843, by digging from the outside until the former excavation in the centre was reached. In carrying out this design the following interments were discovered, all of which seem to pertain to a much more remote era than the interment whose discovery has been before recorded. First, the skeleton of a child, in a state of great decay; a little farther on a lengthy skeleton, the femur of which measures nineteen and a half inches, with a rudely ornamented urn of coarse clay deposited near the head; a small article of ivory, perforated with six holes, as though for the purpose of being sewn into some article of dress or ornament (a larger one of the same kind was found in a barrow at Gristhorpe, near Scarborough, in 1832); a small arrow-head of gray flint, a piece of iron-stone, and a piece of stag's horn, artificially pointed at the thicker end, were found in the immediate neighbourhood of the urn. Between this skeleton and the centre of the barrow four more skeletons were exhumed, two of which were of young persons; there was no mode of arrangement perceptible in the positions of the bodies, excepting that the heads seemed to lie nearest to the urn before mentioned. Amongst the bones of these four skeletons a small rude incense cup was found, which is of rather unusual form, being perforated with two holes on each side, opposite each other.

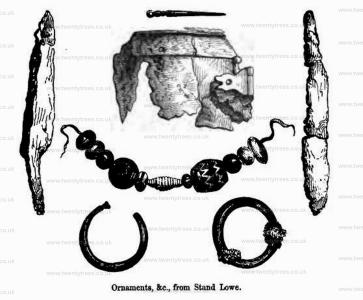

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the 19th of June, 1845, a very interesting barrow, called Stand Lowe [Map], was opened, which is situated upon an elevation, opposite to Moot Lowe [Map], on the other side of the Dovedale road. On digging towards the centre of the barrow, numerous chippings of flint were found, amongst which were six rude instruments, mostly calcined, one of which had been used as a saw, and is very curious; about the same place was found a broken whetstone. The centre being gained, an iron knife was found, of the kind attributed to the Saxons by the modem school of antiquaries, which was immediately followed by a bronze box, of a circular form and much decayed, ornamented by rows of little indented dots, and having a moveable handle, wrought into the form of a serpent's head, the eye being perforated through for convenience of suspension the hinge of the lid is very perfect, and of workmanship which would not disgrace a Birmingham artisan of the present day; near this box lay a small knife which appears to have been protected by an iron sheath, two bronze rings, which had evidently been used as buckles or fibulae, and some other articles of iron, which bear evident marks of having been folded in linen, and are now so shapeless from the effects of rust, that it is difficult to assign a use for them. About the same place was found a small piece of a ribbed vessel of thin yellow glass. There being no indications of bone, or change of colour in the soil, the scrupulous care, so necessary on these occasions, was not used; consequently, the hack was struck amongst a quantity of glass-beads, fortunately, one only was broken; on examination were found eleven glass beads of various shapes and sizes, three of which are remarkably variegated; a bead made of silver wire twisted in a spiral form, and diminishing in the size of the whorls each way from the centre; and a silver needle, with a curiously-formed eye. Amongst the beads were picked up the remains of twenty-six human teeth, consisting merely of the enamel or crown of the tooth; which, owing to some cause perhaps the nature of the soil were the only vestiges of the primeval beauty over whose mouldering remains this barrow had been raised by the hand of affection. At the time of interment the beads were doubtless placed round the neck and from the position of the box, knives, and rings, it is equally evident that they lay on the left side of the body. In Douglas's "Nenia Britannica," plate 18, page 72, a somewhat similar box, containing thread, and a similar needle are figured, which were found in a barrow at Sibertswold, in Kent, opened by Dr. Faussett, about the year 1767. The fact of finding instruments of flint with an interment of this comparatively modem description is rather remarkable, but not by any means unprecedented.

Thomas Bateman 1845. Also on the 14th of June, 1845, was opened, at Castern [Map], about a mile and a half distant from Wetton, a large barrow, measuring about thirty-five yards in diameter, and from four to five feet in height. About four yards from the centre, on the south side of the mound, a small square cist, constructed of thin limestones, was discovered. It contained the skeleton of an infant, which lay amongst the mould in the upper part of the vault; whilst upon the floor of the cist was a deposit of calcined human bones, accompanied by two bone pins, also burnt, one of which is perforated with an eye, and a fine spear-head of flint, with a small arrow-head of the same material. On the natural level, in the centre of the tumulus, lay the skeleton of a female with the knees contracted, completely imbedded in rats' bones, amongst which was found the upper mandible of the beak of a species of hawk. In a deep cist, cut in the rock, beneath the last-named skeleton was another interment evidently the skeleton of a man who had been buried in a sitting posture with whom was deposited part of a flint spear-head. In other parts of this tumulus were found portions of skeletons pertaining to two children and one full-grown person; the various bones of two human feet in a perfect and undisturbed state pieces of stag's horn, horses' teeth, a small whetstone, a large piece of rubbed sandstone, a circular instrument, and various chippings of flint, and the handle of a knife, composed of stag's horn, riveted upon the steel in the modern way; nevertheless it must be of considerable antiquity, being found eighteen inches deep in the barrow, and where the soil was as solid as though it had never been removed. Still its high antiquity is doubtful, though some future discovery may decide the question favorably. In Douglas's 'Nenia Britannica,' plate 19, fig. 4, one very similar is figured, which is of undoubted antiquity, having been found with the interment in one of the barrows upon Chartham Downs, in Kent.

Barrows near Arbor Low. On the 15th of March, we re-opened a barrow near the boundary of Middleton Moor, in the direction of Parcelly Hay [Note. Possibly Parsley Hay Barrow [Map]], which was unsuccessfully opened by Mr.W. Bateman on the 28th of July, 1824; nor did our researches lead to a more satisfactory result, as the entire mound seemed to have been turned over by deep ploughing by which the interments, consisting of two skeletons and a deposit of burnt bones, had been so dragged about as to present no characteristic worthy of observation. A neat whetstone was picked up amongst these ruins, and a carefully chipped leaf-shaped arrow-point of flint has since been found by ploughing across the barrow. About fifty yards South-east of the last, is another barrow of very small size, both as to diameter and height; so inconsiderable indeed are its dimensions, that it was quite overlooked in 1824. Fortunately the contents, with the exception of one skeleton that lay near the surface, had been enclosed in a cist, sunk a few inches beneath the level of the soil. As in the companion barrow, the skeleton near the top was dismembered by the plough, so that it afforded nothing worthy of notice - the original interment, however, which lay rather deeper, in a kind of rude cist or enclosure, formed by ten shapeless masses of limestone, amply repaid our labour. The persons thus interred consisted of a female in the prime of life, and a child of about four years of age; the former had been placed on the floor of the grave on her left side, with the knees drawn up; the child was placed above her, and rather behind her shoulders: they were surrounded and covered with innumerable bones of the water-vole, or rat, and near the woman was a cow's tooth, an article uniformly found with the more ancient interments. Round her neck was a necklace of variously shaped beads and other trinkets of jet and bone, curiously ornamented, upon the whole resembling those found at Cow Low [Map] in 1846, (Vestiges p. 92,) but differing from them in many details. The various pieces of this compound ornament are 420 in number, which unusual quantity is accounted for by the fact of 348 of the beads being thin laminae only; 54 are of cylindrical form, and the 18 remaining pieces are conical studs and perforated plates, the latter in some cases ornamented with punctured patterns. Altogether, the necklace is the most elaborate production of the pre-metallic period that I have seen. The skull, in perfect preservation, is beautiful in its proportions, and has been selected to appear in the Crania Britannica, as the type of the ancient British female. The femur measures 15¼ inches. The engraving represents the arrangement of the cist.

Wiltshire Museum. DZSWS:STHEAD.49. 1 flat whetstone of green Siliceous Stone (fine grained) found with a primary inhumation in bowl barrow Winterbourne Stoke G8 [Map], excavated by William Cunnington.

Wiltshire Museum. DZSWS:STHEAD.49a. 1 flat white quartzite whetstone found with a primary inhumation in bowl barrow Winterbourne Stoke G8 [Map], excavated by William Cunnington.

Wiltshire Museum. DZSWS:STHEAD.72. 2 double ended slate whetstones with round ends, flat one side and convex on the other, found with a primary inhumation in bowl barrow Winterbourne Stoke G54 [Map], excavated by William Cunnington.

Wiltshire Museum. DZSWS:STHEAD.75a. 1 sandstone whetstone rubbed flat on two sides found with a primary (?) cremation in long barrow Winterbourne Stoke G53 [Map], excavated by William Cunnington.