Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that `abled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page.

Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Archaeologia Cambrensis 1927 Pages 1-43 is in Archaeologia Cambrensis 1927.

The Capel Garmon Chambered Long Cairn [Map]. By W. J. Hemp, FSA.

THE monument at Capel Garmon, known locally as the Cromlech, but better described as a chambered long cairn, is in the parochial chapelry of Capel Garmon (alias Garth Garmon) end the parish of Llanrwst, and about five miles a little east of south of the town of that name. The site lies at a level of 800 ft. on one of the successive terraces by which the high moorland known as the Hiraethog descends to the valley of the River Conway. As is often the case in North Wales, the position seems to have been chosen so that the tomb itself would have been irconspicuous; but the view which it commands is very wile and extraordinarily beautiful, comprising as it does the whole eastern sweep of Snowdonia. It is placed on the edge of what is now an undulating meadow clase to and overshadowed by one of the many small out:rops of rock which are characteristic of the district, and themselves often have the appearance of being artificial mounds. It may be partly due to the fact that it blended so loi with its surroundings that it so long escaped the destruction which has overtaken the majority of its fellows; but its existence has probably been known for some long time past, as the name of Maes y garnedd, or "the field of the cairn," once applied to the land containing it,1 and the field in which it stands is called Caer ogof, or the field of the cave.

Note 1. The farm is now divided into two—Maes y garnedd and Tyny y coed—the cairn being on the latter.

Note 2. B. 464, fol. 20, recto. I have to thank Mr. J. Goronwy Edwards, of Jesus College, for kindly making the transcript.

The monument must be considered as a member of a group of chambered cairns which occupied the Conway valley and belonged to the large body of North Wales megalithic structures most strongly represented in Anglesey and on the coasts of Carnarvon and Merioneth. The nearest example is the Maen Pebyll long cairn, just over two miles distant, in the hamlet of Nebo, at a height of about 1,200 ft. The general outline of this has been preserved and bears a strong resemblance to that of Capel Garmon. For a plan and description see Archeologia Cambrensis, 1923, pp. 143-7. There was once a group near Cerrig y Drudion, about 1,000 ft. high, by the sources of the eastern branch of the river Conway (Royal Commission Report, Denbighshire, No. 98). Other examples are the group at Ro Wen, at a height of 1,000 ft.; the "cromlech" at Porthllwyd, about 25 ft. above sea-level—these being on the western side of the valley; one at Hendre Waelod, also low down, on the eastern side, and the almost intact long cairn on the Great Orme's Head. Outliers to the east are the chambered cairn at Tyddyn Bleiddyn and the remains of a "cromlech" in Kinmel Park, both in the broken country between the Conway and the Clwyd valleys.

The earliest description is given by Edward Llwyd, the Welsh topographer and "Keeper of the Ashmolean Repository in Oxford." He visited the monument at the very end of the seventeenth century, probably in the year 1699, and his account of it is preserved among the Rawlinson MSS? in the Bodleian Library.

"Qgo ty'n y koed yng hae'r ogo yn agos i Gappel Garmon ym hlwy Lhan Rwst. Karnedh vawr hir o Gerrig ond bod daiar gwedi tyvy drosty ag ymbelh bren derw a chriavol ar ucha hynny. hyd y Garnedh ymma yw tri ar higeint o'm kamme i. Ei lhed ar i thraws oedh deydheg. Am i lhyn mae hi'n oval ag yn kodi yn Geven yn dhigon tebig i Garnedhi hengwm yn Ardydwy. Ag megis y mae tair kromlech yng harnedhi hengwm velhy y mae tair ymma; ond darvod torri Dwy o honynt yn dhiwedhar. Y drydydh sydh etto iw gweled lhe y gossodwyd hi gynta; ag mae hi o riw lyn go grwn ond i bod yn amgonglog ag yn acliniedh dhigon. I maint o hyd ag ar draws alh vod yng hylch pedeir lhath, a'i thrivch droedvedh ne lai. Odhi deni mae hi'n byrIlwvn; ag mae ynghylch §n ar dheg o Gerrig yn i chynnal hi. Rhai y dhyweid y gnottie 'r hén Gymry ney'r Gwydhelod loski tin odhi denni ond ni welsom ni odhi denni dhim amgen na lhawer o gagal devayd. Yn Garreg vechan triochrog a gowsom yn inig gwedi i chaboli; a honno ar ben yn o'r kolovne megis yn wrthwl rhwng y Golovn a'r Gromlech."

This may be translated as follows:

"Tyn y coed Cave in the Field of the Cave, near Capel Garmon, in the parish of Llanrwst. It is a great and long cairn made of stones, but covered with earth, and having occasional oak and mountain-ash trees growing upon it. The length of this cairn is twenty-three of my paces, its breadth twelve. Its shape is oval and it rises to a ridge like the Carneddau Hengwm in Ardudwy. And as there are three cromlechs at Carncddau Hengwm, so are there three here; but two have recently been broken up; the third can still be seen in it: original position; its form is somewhat rounded, but it is angular and unshapely. Its length and breadth are about four yards, and its thickness a foot or less. The underside is very smooth, and there are about eleven stones supporting it. Some say that the old Welsh or Irish were accustomed to make fires beneath it, but we saw nothing underneath but a mass of sheep's droppings. We saw one small three-cornered stone only that had been worked, and this was on the top of one of the columns, acting as a wedge between the column and the cromlech."

Another description, a century and a-half later, is to be found among the menuscript notes of the late Archdeacon John Evans, dated 1852, and entitled "History of Pentre Voelas and District." Two copies of these notes are preserved; one at Pentrefoelas Vicarage, the other at Voelas Hall. To this last copy additions have been made from time to time by the late Colonel C. A. Wynne-Finch (the owner of the monument) and his son and successor, Major J. C. Wynne-Finch. Selections from the Archdeacon's notes were printed in Archaologia Cambrensis for the year 1856, p. 91, and in the first volume of the Cambrian Journal, dated 1854, p. 75.

This description is worth quoting, as it records the condition of the cairn before any attempt at careful examination had been made, and, moreover, is not easily accessible.

"Tynycord Cromlech - Capel Garmon, Denbighshire [Map]."

"This is a remarkably fine specimen of an Ancient sepulchral chamber in excellent preservation. It was once embedded in a tumulus or carnedd, as was the case with most of our cistveini and Cromlechau. The incumbent heap has been half removed for building walls.... The Leading outline of the tumulus is elliptical, its greatest diameter at the base being 20 yards, its east 13 yards. It has been reduced in size within living memory. Level with the present surface of the mound is the denuded roof of the Cromlech, a flat slab of marvellous size and symmetry. Its form is rhomboid, or symewhat lozenge-shaped, its greatest length 14 feet 7 inches, its breadth 11 feet 4 inches... exceeding, I apprehend, in superficial measure any Cromlech in Wales. Its average thickness is about 15 inches. Under one end or apex is the entrance to the cell pointing to the South West, opposite the other at a distance of 2½ yards is a circle 2 yards in diameter, composed of seven stones about 2 feet out of the ground, at unequal distances, as if some of them had been removed. A line drawn lengthways over the large slab from the entrance of the cell would intersect this circle. There are no other traces of systematic arrangement outside the monument. A deep lane, 4 yards long, which appearsto have been once a covered way, leads to the entrance of the chamber. This has been converted into a stable by a former tenant and provided with a door and window, and with a manger at the end opposite the door. The shape of the chamber inclines to a pentagon, the doorway forming one side. Its height at the door is 5 ft. 5 inches, at the middle 5 ft. 7 inches, gradually increasing towards the opposite end. The supporters, which partly form the walls of the stable, are five in number, and measure respectively 5 ft. 5 inches high by 4 broad; 5 ft. by 2 ft.; 6 ft. by 3 ft. 4 inches; 5 ft. 9 inches by 2 ft., and 5 ft. by 3 ft. 6 inches. They stand at regular distances and the intervening spaces have been built up with a wall of small stones, a few of which, by their aged, greenish colour, seem composed of a broken portion of the Cromlech. The floor is paved; some of tae supporters appear disturbed from their original position and somewhat broken. Still, so neatly and free from damage, on the whole, has the conversion been made from the sepulchre of a hero to a stable for colts that no one would wish the work undone nor the integrity of the structure better secured."

"All the stones of the Cromlech are of the argillaceous stone, or flags, with which the country abounds. Someone has been barbarous enough to attempt to blast the large cover stone. But the hole being bored too deep the underside of the stone gave way, the laminæ being forced out in concentric circles, diminishing upwards and presenting an object, that if unexplained, might perplex an antiquary."

It is evident from this description and from the plan published in the Cambrian Journal that the eastern chamber was only represented at this time by the tops of the upright stones and that the existence of the central chamber and the passage was not suspected. Very shortly after it was written a careful examination of the monument was made, and the results were duly recorded in the Voelas Hall copy of Archdeacon Evans's notes in the following words:—

"The carnedd at Capel Garmon was opened carefully, November 9th, 1853, in the presence of W. W. E. Wynne, Esquire (of Peniarth), M.P., and a party from Voelas—C. G. Wynne—F. E. Wynne—J. Seymour Wynne, and others. The structure within resembles the letter T, consisting of three chambers in a line running East and West perpendicular to which is a long entrance passage, opening into the central chamber. This chamber is oblong and sub-divided by two upright flagstones into three compartments. At each end it opens into two other chambers, one of which is circular, and the other, which has its cromlech roof still entire, appears also to have been circular before some of its stone sides were displaced in order to form a stable, for which a new entrance was excavated through the west side of the carnedd. The cells were formed on the natural surface of the ground, increasing in height, according to the distance from the entrance, which was on the upper side of the slope.

"The entrance consists of two upright stones, two feet high and the same distance apart. After entering there is a descent of about a foot, by three steps and then the passage expands considerably about the middle, and contracts again to two feet on entering the central chamber. It gradually increases in height until at the inner end it is four feet six inches high. This passage, as well as the cells, was no doubt covered, and all the interstices between the upright stones were here, as well as elsewhere, filled up with remarkably neat stone work in courses of uniformly thin stones. If the covers of the passage rested upon the present uprights, as appears to have originally been the case, the entrance must have been only two feet square, and just large enough to admit a man on his hands and knees. Some of those living in the neighbourhood say thas within living memory the cromlech was covered over with carnedd stones, but when, and by whom, the cells were violated and their covering stones broken cannot be ascertained."

All About History Books

Henrici Quinti, Angliæ Regis, Gesta, is a first-hand account of the Agincourt Campaign, and subsequent events to his death in 1422. The author of the first part was a Chaplain in King Henry's retinue who was present from King Henry's departure at Southampton in 1415, at the siege of Harfleur, the battle of Agincourt, and the celebrations on King Henry's return to London. The second part, by another writer, relates the events that took place including the negotiations at Troye, Henry's marriage and his death in 1422.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

The history of the monument is carried a step further by a still later addition to the Voclas Hall notebook made by Colonel Wynne-Finch in 1896:—

"I fear it (the cromlech) is no longer in a good state of preservation. The action of the weather has told severely on the walls of small stones which support the sides and names have been cut and painted on the large stones as well. The Secretary of the Cambrian Archeological Society, who visited the cromlech in 1880, was so struck with this fact that he offered to give £10 towards fencing the cromlech round, but I considered that, unless a custodian could be appointed, lodged and paid, who could (on the spot) look after it, it would be useless to attempt to protect it—partially—and I also thought that so much damage had already been done (in 1880) that it would hardly be worth going to much expense to preserve the remnants of a once interesting relic of antiquity and so decided to leave it as it was, giving general, but careful, instructions to the tenant at Tyn y cued to look after the cromlech—which had been walled round—as well as he could."

In 1920 Major J. C. Wynne-Finch decided to sell Tyn y coed farm, but, before doing so, he offered the custody of the cairn to H.M. Commissioners of Works. The offer was accepted, and shortly afterwards the wall was removed and replaced by a wire fence.

The condition of the monument caused some anxiety, as several of the upright stones of the eastern chamber were considerably ou: of the perpendicular. The removal of the weighted covering stones had allowed the pressure of the mound and the growth of trees to force some of these uprights inwards, while in several cases this movement had caused the collapse of the dry walling which filled the intervals between them. This walling was also suffering from visitors clambering in and out of the chambers when exploring the monument (Fig. 3). The remaining cover stone was badly cracked along natural lines of cleavage, a condition which had no doubt been aggravated by the attempt to blow up the stone.

Work of preservation was taken in hand. in the spring of 1924, and continued intermittently from February 27 to June 6. The great majority of the working days were wet or snowy ones, a circumstance which, in addition to causing continual delays, badly hampered one important part of tke work and caused a considerable amount of it to be left unfinished for the time being, namely the search for "relics" which might provide evidence for dating the period of the construction and use of the monument. It was essential that any material which had to be displaced should be closely examined, and this could only be satisfactorily done when the soil was dry enough to sift.

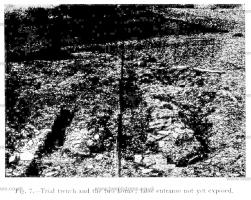

The first business was the removal of the trees growing freely on the mound (Figs. 3, 4, 5). These trees, although very attractive and picturesque—several of them were very old dwarf oaks and mountain ashes, two being 25 ft. high—were seriously threatening the stability of the structure, both by the penetration and growth of their roots and the wrenching and shaking which they caused in stormy weather. Some of the largest had been cut down a year previously, but the stools remained, and their removal was a long and troublesome task and one which had to be carried out with great care as, in addition to the risk of destroying constructive details by careless handling, at two points ancient trees had preserved what appeared to be patches of the original surface of the mound. This work occupied from one to three men for practically the whole period. Apart from it, the first task was the removal of the foundations of the modern wall, which choked the entrance to the passage. This at once led to discoveries. In the first place, there was no trace of the three steps described in the report of the work done in 1853, and the existence of a hole under the site of them, made by a crowbar and containing fragments of glass, showed 'that they must have been moved at that time. It is probable that they were fallen stones for; as the work proceeded, it became evident that the original floor of the passage had not been exposed before 1924.

The Internal Wall

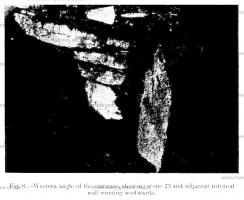

The second discovery was that the side walls of the passage, instead of curving outwards to form an approach, returned north and south at right angles (Fig. 6). This at once suggested that the current theory of an oval mound would have to be revised. The return walls were built of slabs of stone similar to, but rather larger than, those employed in filling the gaps between the uprights of the passage and chamber.

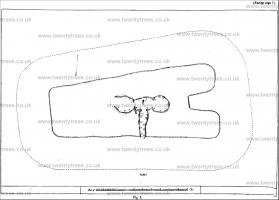

A number of trial cuts were then made to discover the direction and extent of these walls; this work proved to be extremely difficult and tedious. It was neither desirable nor possible to expose the complete course of the wall, and equally undesirable to disturb the mound by cutting deep trenches. The result was that in order to search for a buried wall face which might be found a foot or more out of its expected position, or even have been completely destroyed, it was often necessary to excavate down into a mass of shifting stones which had already been disturbed, either by human agency or by the growth and decay of trees. Both ends of the mound had been ploughed over many times, and in places all the stones of the wall had been scattered. Eventually, however, it was possible in one way or another to determine the true position of the complete circuit of the internal wall. The resulting plan (Fig. 1) shows an oblong having three straight sides, the fourth being occupied by two "horns" flanking an entrance. This entrance, however, is a false one, the true approach to the chambers being by the passage in the centre of the southern side.

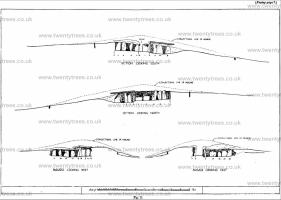

At several points where the actual wall had entirely disappeared, particularly at the west end, the original line of the face could be traced by an interesting structural feature. Small slabs of the shaly rock of the district were set on edge in the natural soil of yellow clay at right angles to, and bearing against, the lowest course of the wall, which they thus served to buttress against any tendency to spread outwards. They were surprisingly firmly set, and must have been hammered into position. Where the wall and mound were preserved to a greater height, it could be seen that these stones, which were set against the foundation course at a raking angle, were reinforced by others so set as to lean against and support the wall; in fact, this principle seems to have been observed throughout the construction of that part of the mound which lay outside the internal wall. Within the limits of the examination actually made, all the stones were so laid as to contribute to its support. This is illustrated by the section at the east side of the entrance (Fig. 2). Here, as it happened, was the only place where time allowed a fairly complete and satisfactory section to be cut.

The Entrance

Close examination of the area immediately outside the entrance led to the unexpected conclusion that this could never have been fully reopened after the construction of the mound had been completed, and further, that completion, i.e., the reinforcing of the internal wall, must have been carried out very shortly after building, the original soil on which the reinforcement was laid being quite free from vegetable deposit and showing no signs of disturbance. It is true that the upper portion of the mound immediately outside and opposite to the entrance had been disturbed, but to no greater extent than might have been expected to result from the work carried out in 1853. The lower levels at this spot appeared to be untouched, and it was morally certain that the material covering the threshold stone itself had never been disturbed.

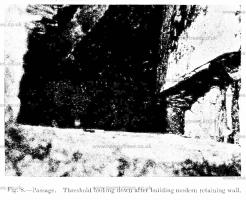

No evidence remained to show how the actual entrance was closed, but on the analogy of other monuments the "door" is likely to have been formed by a single stone, held in position by the mound. The two threshold stones (Fig. 8) were placed immediately outside the uprights which form the angles on either side of the entrance, and were laid directly on the undisturbed soil at the level of the passage floor. There would therefore originally have been a step down equivalent to the thickness of the stones—3 in. to 4 in. At the completion of the recent preservation work a new retaining wall was built in such a way as to expose the greater part of the threshold and a few inches of the original internal wall on either side of the doorposts. This was done in order that a sample of the walling might remain visible without endangering its stability. It was noticeable that both here and elsewhere the upper part was built of longer and thicker stones than ll employed in the lower courses. The wall must originally re risen to a height of at least 4 ft. above the top of the threshold on either side of the entrance.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Abbot Ralph of Coggeshall

Describes the reigns of Kings Henry II, Richard I, John and Henry III, providing a wealth of information about their lives and the events of the time. Ralph's work is detailed, comprehensive and objective. We have augmented Ralph's text with extracts from other contemporary chroniclers to enrich the reader's experience.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

The Mound.

Examination of the covering mound or cairn was especially difficult owing to the nature of its materials and construction. The main body of it was entirely of stones, many of a laminated type; these as a rule were laid flat. The average size of the stones at the top of the mound was smaller, but this may have been partly due to the recent abstraction of the larger ones. It is possible that when completed the cairn was covered with turf, and of late years it had been entirely overgrown. When stones were moved, dry earth and disintegrated stone filtered down among the interstices and blanketed everything, and to remove this rubbish without disturbing the arrangement of the stones was an almost impossible task (Fig. 17). The mound seemed to have no constructional elements. But there was no opportunity for an examination such as Mr. John Ward successfully made of the Tinkinswood long cairn at St. Nicholas in Glamorgarshire.1 Wherever 1t is possible to trace it, the outer margin of the mound now lies about six yards outside the line of the internal wall.

Note 1. Arch. Camb, 1915, pp. 306-16.

The False Entrance

The tops of three stones placed on edge, but not in the same straight line, were just visible above the surface near what at first appeared to be the eastern end of the mound, and it was thought likely that these might belong to a secondary "cist." Eventually, however, it became clear that they formed the "door" of a false entrance, and further examination proved without any doubt that there never could have been any access at this point to the interior of the mound (Figs. 1 and 9). The three stones, together with a fourth which did not project above the level of the soil, were originally two in number, two fragments having split off from the larger stone, possibly as the result of the ploughing which has broken off an appreciable amount of each. The upper part of the larger one had inclined considerably to the east, but the position of its base had not been altered. It was eventually pushed back into place and two broken pieces wedged in position.

The western half of the area between the horns was carefully and thoroughly examined down to the yellow clay which marked the original ground-level at all parts of the site which were examined. In some places, however, the clay had been relaid, and so clean was it that it was often difficult to be certain whether it had been disturbed or not. The clay was found to be 10 in. higher on the eastern face of the upright door stones than it was on the west. On the east side it had certainly been relaid to a depth of 10 in., and had probably been moved to facilitate the insertion of rounded packing stones, one of which was placed under the northern end of the larger door stone. The packed yellow soil reached within 2 ft. of the top of the stone. Inside was disintegrated shale resting directly on the original surface.

Raking stones set edgewise in the clay at right angles to the internal wall were found all over the area cleared between the horns, and their existence there seemed to prove conclusively that the false entrance was deliberately hidden by the covering cairn as soon as it had been constructed. It is, of course, possible that the internal wall was carried up to such a height that its uppermost courses showed above the surface, but all evidence on this point has gone. It is also possible that the upright stones of the " entrance" were capped by a lintel resting on the walling on either side and forming a porch. Precedents could be found for such an arrangement, and the stones have certainly lost some of their height, but they are thin, and again, there is no evidence. Here, and wherever else areas immediately outside the internal wall were examined, a scattered line of small blocks of white quartz was found encircling it. Some of these appear in Fig. 9, though not in their original position.

One incomprehensible discovery was made in this area. The wall of the northern horn was found to stop suddenly 6 ft. 6 in. from the "door," and further investigation showed that a hole had been sunk at this point, and at the original ground-level were two slabs of slate, together measuring 5 ft. in length and averaging rather under 2 ft. in width. They proved to have been carefully and gronly laid directly on the clay, which here was about 1½ ft. below the modern ground-level. Above the slabs was the replaced shaly material of the mound containing no relics of any kind; below them was nothing but undisturbed soil. The area surrounding them to the south and east had not been disturbed, but the walling had been destroyed right up to the "door." The laying of the slabs in this position must have been a quite laborious task, and no reasonable explanation seems to be forthcoming. All that can be said with certainty is that it must have been done within the last century or so, as an edge of one of the slabs had been carefully trimmed by a circular saw of modern type.

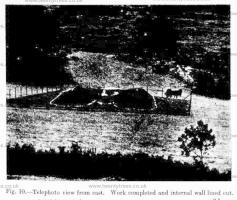

When the work had been completed and the turf replaced, the area between the horns was left at a slightly lower level than the adjacent part of the mound in order to make it clearly ind it by while the complete circuit of the internal wall has been marked out by a line of small stones set in the turf, as it was out of the question to leave it exposed (Fig. 10).

The Passage

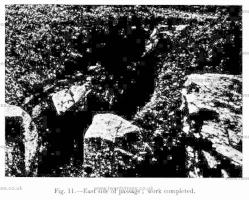

The only area which was completely examined was the passage. Three of the upright stones showed evident signs of having shifted on their bases, and the majority were inclining inwards and appeared to be insecure. It was thought that, as in the case of the chambers, the removal of cover stones had allowed the pressure of the mound to force the supporters out of the perpendicular. Fortunately this was not the case, as close examination proved that the southern part of the passage had originally been covered by a corbelled roof and that the uprights were deliberately inclined inwards (Fig. 11). Some of the remaining upper courses of the dry walling definitely oversail and are built of long stones set deep in the mound, which show no signs of having shifted, while the eastern doorpost of the outer entrance, although somewhat inclined westwards, fits tightly against the end of the internal wall which butts up against it.

Eventually it was only found necessary to reset three of the upright stones; namely, the two flanking the inner entrance to the central chamber (Nos. 16 and 17), which had originally been secured by a cover stone, and the adjoining stone on the eastern side of the passage (No. 29), which had come considerably forward, and in doing so had dislocated the dry walling on either side of it (Fig. 12). This stone was reset in its old position in concrete. The greater part of the panel flanking it on the north had collapsed and was rebuilt (Fig. 11), and that on the south had moved with the upright, 80 much so that above the four lowest courses it had to be rebuilt stone by stone (Fig. 12). When once such walling was out of position, it was only in very exceptional cases that it was possible to replace it without rebuilding, partly because the loose material at the back at once settled into any cavity, and also because the shaly nature of the stones selected by the original builders had often caused them to disintegrate badly. Happily, it was possible to save the corbelling above this panel owing to the use of the long stones already referred to, which remained firm in spite of the cavity beneath them (Fig. 12). It was also found possible by underpinning to retain the corbelling intact from this point to the end of the passage on the eastern side. 1 ft. 6 in. of the panel between stones 27 and 28 had to be rebuilt immediately beneath the corbel stone (Fig. 11), and five small stones were inserted to replace the narrow filling between stones 27 and 26. At one point, above the northern end of stone 28, one corbel stone projects 8 in. beyond the top of the upright, and its end reaches the central line of the passage (Fig. 12). Other corbels adjoining it on the south have almost as great a projection. On the western side of the passage no rebuilding was necessary, although a certain amount of the walling had previously been pawhed and repaired, and four new courses were added to the fifteen old ones between stones 22 and 17. The corbelling on this side is not so well preserved.

All About History Books

Abbot John Whethamstede’s Chronicle of the Abbey of St Albans

Abbot John Whethamstede's Register aka Chronicle of his second term at the Abbey of St Albans, 1451-1461, is a remarkable text that describes his first-hand experience of the beginning of the Wars of the Roses including the First and Second Battles of St Albans, 1455 and 1461, respectively, their cause, and their consequences, not least on the Abbey itself. His text also includes Loveday, Blore Heath, Northampton, the Act of Accord, Wakefield, and Towton, and ends with the Coronation of King Edward IV. In addition to the events of the Wars of the Roses, Abbot John, or his scribes who wrote the Chronicle, include details in the life of the Abbey such as charters, letters, land exchanges, visits by legates, and disputes, which provide a rich insight into the day-to-day life of the Abbey, and the challenges faced by its Abbot.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

The cunning and skill shown by the builders in the various methods they adopted to secure their stones from any danger of slipping were admirable. The uprights were set in pockets and, where necessary, their bases carefully packed with stones; while Lhuyd's description of the monument suggests that wedges were inserted between the cover stones and such uprights as would otherwise be too short to give support and so might themselves become insecure.1 Another interesting device was adopted to secure the lowest course of the dry wallirig, namely, the driving in of long and thin stone pins Bim under the foundations, in place of the raking stones used for the internal wall; while the upper courses, wherever possible, were wedged tightly between the uprights.

Note 1. The photographs illustrating the recently-discovered vast burial-chamber at La Huogue Bie, in the Island of Jersey, show this constructional feature with great clearness. See the Bulletin Annual of the Société Jersiaise for 1925.

When the passage was being cleared it seemed likely that some of the flat stones lying on the floor might have been so placed as stretchers to give additional support to the bases of the stones, but this was probably not the case. Some of these stones have, however, been relaid as found, and the general level of the floor brought up even with their tops before the whole was turfed over in order to preserve it. It may, therefore, be assumed that the present floor of the passage is 3 in. or 4 in. above the level left by the builders. The upper few inches of the clay had been relaid, the maximum depth 80 treated being 6 in. Fragments of charcoal in places were the only indication of the junction between disturbed and natural clay.

It was fortunate that the fallen stones had effectually sealed the floor of the passage, as the result was the preservation of a few pieces of pottery, to which it is possible to assign a reasonably accurate date. These were of two types; fragments of red pottery of "beaker" type were found at three points, between stones 17 and 22 and 28 and 29, in each case pressed into the floor close against the wall of the passage and under the fallen stones, and between 23 and 28; while much wearisome sifting of the finer material removed from the passage produced a single fragment of coarse black pottery of neolithic type, together with one small flint flake, certainly an importation into the district. Dr. Cyril Fox, formerly Keeper of the Department of Archaeology, and now Director of the National Museum of Wales, which will have the custody of the pottery for exhibition in North Wales, has kindly reported on it (Appendix I).

Another discovery of some Interest was that at a point about 2 ft. from the entrance to the chambers, on the west side of the passage, a patch of the yellow clay of the floor, about 1 ft. 6 in. in diameter, had been reddened by fire to a maximum depth of 2 in. Underlying the western side of this patch was a pocket of soft brownish clay containing some fragments of the reddened clay (possibly carried down by some small burrowing animal), and also some small quartz crystals—these were not found anywhere else, and their presence may be fortuitous. This pocket continued under the dry walling and extended as far as the western stone of the entrance (No. 17). The northern end had been filled by a stone of some size, which served as a foundation for the wall. It was not thought desirable to finish exploring this pocket for fear of weakening the wall aboveit. In all probability the hole either had originally been filled by a natural boulder, which had to be removed, or else had been made for some purpose in connection with the erection of the monument. In any case it was filled in at the time of building. At the opposite side of the passage was a vertical hole 2 in. in diameter and 8 in. deep. In it was a black substance which appeared to be decayed wood. Another filled-in pocket in the original ground was found between the two doorposts of the inner entrance. It was about 14 in. deep and measured 1 ft. 9 in. from east to west and 1 ft. 6 in. from north to south. It was bowl-shaped and filled with clay similar to that in which it was sunk, but containing fragments of charcoal.

At the back of store 29, among the stones of the mound and about a foot above ground-level, were found two bones. It is probable, but not quite certain, that they had been placed there when the mound was built. They are No. 1 in Appendix II, which contains the report which Dr. W. H. L. Duckworth, of the Anatomy School, Cambridge, has very kindly made on the bone fragments found in the monument.

The Central Chamber

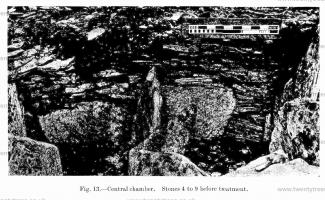

The passage leads directly into the central chamber through an entrance about 2 ft. 6 in. wide. The chamber measures about 11 ft. from east to west, and the extreme width is about 6 ft. 6 in. A stone (No. 6) is placed on end at right angles to and a little west of the centre of the northern side of the chamber. At the southern end of this a thin slab (No. 7) is placed at right angles to it, the two together forming a pair of alcoves within the chamber (Fig. 13). No. 7 stone had been broken in two and had canted over to the east: as there was clear evidence of its original position, it has now been set up again and the broken portion riveted in place.

The two stones on either side of the entrance (Nos. 16 and 17) had both come forward several inches. The bases, however, had not shifted, and it was a comparatively simple matter to push them back into position, as a sufficient amount of the ancient dry walling remained in situ to enable them to be replaced with complete accuracy. They were reset in concrete, as it was necessary to secure them by some artificial method owing to the loss of the cover stones which once held them.

Fifteen courses of old walling remain in the passage between stones 17 and 22, and four new ones were added in order to raise the wall to a sufficient height to retain the stones and soil of the mound. Between stones 17 and 18 a very narrow panel of old walling had entirely gone, and was replaced. South of stone 16 in the passage there were only three courses of old masonry, which had to be reset stone by stone, and a considerable amount of new masonry placed above them, while the whole of the panel between stones 16 and 15 also had to be rebuilt, the lower part with the old stones. It was the masonry on either side of stone 16 which had suffered the greatest damage from visitors climbing in and out of the chamber, and it was thought desirable to raise the walls to something like their original height in order to make this practice more difficult.

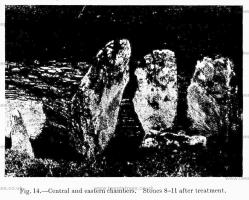

The walling on the north side of the chamber, above and on both sides of stone 8, was extraordinarily well preserved, probably to its full height; the last four courses were corbelled, as in the case of the chambers in Uley barrow in Gloucestershire. The panel between stones 8 and 9 looked very insecure, but it was possible to bring it back to its original state of security by the insertion of a single course of stones in place of one which had decayed (Fig. 14).

The narrow panel between stones 4 and 5 was of recent construction, as was the western portion of the walling above stone 5 (Fig. 13). When this had been made sound and brought up to the level of the original work to the east, the whole was covered with a course of long stones, the tails of which were set well back in the body of the mound and eventually covered with turf. As the dry walling here and elsewhere had lost the protection of the cover stones, special steps had to be taken to prevent the risk of it collapsing, and the method employed was that which the original builders had adopted in the case of the retaining walls of the passage.

Thanks to the well-preserved condition of the walling above stone 5, it is possible to reach a fairly definite conclusion as to the manner in which the central chamber was covered. Four inches below the left-hand bottom corner of the board which carries the scale in Fig. 13 1s a stone about 16 in. long, and immediately underneath this was a cavity having a perpendicular depth of 5 in. This ran back for some distance, and it is extremely probable that it was originally filled by a cover stone resting on stone No. 6, immediately in front of the cavity, and also on Nos. 4 and 17. This would have covered the western portion of the chamber and projected under the cover of the western chamber. The eastern portion would have been covered by a second stone, possibly resting on the western cover, on the top of stone 15, and on the shoulder of stone 9 (Fig. 15). It is very probable that this shoulder was deliberately "dressed" in order to serve as a support.

All About History Books

The History of William Marshal was commissioned by his son shortly after William’s death in 1219 to celebrate the Marshal’s remarkable life; it is an authentic, contemporary voice. The manuscript was discovered in 1861 by French historian Paul Meyer. Meyer published the manuscript in its original Anglo-French in 1891 in two books. This book is a line by line translation of the first of Meyer’s books; lines 1-10152. Book 1 of the History begins in 1139 and ends in 1194. It describes the events of the Anarchy, the role of William’s father John, John’s marriages, William’s childhood, his role as a hostage at the siege of Newbury, his injury and imprisonment in Poitou where he met Eleanor of Aquitaine and his life as a knight errant. It continues with the accusation against him of an improper relationship with Margaret, wife of Henry the Young King, his exile, and return, the death of Henry the Young King, the rebellion of Richard, the future King Richard I, war with France, the death of King Henry II, and the capture of King Richard, and the rebellion of John, the future King John. It ends with the release of King Richard and the death of John Marshal.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

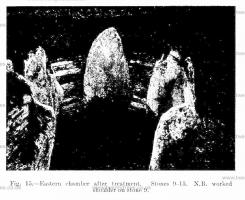

The Eastern Chamber

This is roughly circular, with a diameter of 9 ft. (Figs. 14, 15). Three stones, Nos. 12, 13 and 14, were considerably out of the perpendicular, No. 12 to the extent of 2 ft., No. 13 1 ft. 6 in., and No. 14 just over 1 ft., the result being that these three stones were all ultimately supported by No. 15. In addition, No. 13 had slightly pivoted round. Stone 10 proved to be so insecure after a modern accumulation of stones and soil had been removed from its base, that the pressure of the hand would have been sufficient to overthrow it. Stones 9 and 15 were quite secure and needed no attention. Stone 11, although quite firm and upright, had split from top to bottom along a natural line of cleavage. The crack was filled with a fine cement. Nos. 10, 12, 13 and 14 were secured by having their bases cemented in position. Six courses of old walling remained between stones 9 and 10, but had to be reset on a new foundation. The walling had entirely disappeared between stones 10 and 11. One stone of the foundation course remained between 11 and 12, one course between 12 and 13, and two between 13 and 14 (Fig. 17), while there were 17 in good condition between 14 and 15. There was thus sufficient evidence to bring back the uprights into positions which were quite certainly those originally occupied. The panels between them were filled with new walling, which was carried up to a height sufficient to hold up the body of the mound.

The wide panels between stones 11 and 14 had been roughly filled in modern times, presumably when the chamber was cleared in 1853. When this filling was removed it was possible to examine the structure of the cairn. Large stones were laid at the bottom and somewhat smaller above. No earth, however, was to be found among the undisturbed: stones save a certain amount of humus which had been washed down among them (Fig.17).

The uprights had been firmly set in the clay and held in position by stones wedged under and against their bases. The lower courses of the dry walling were also held in position by stone "pins" driven diagonally under the bottom course, as in the passage. The upper courses were so set that, wherever possible, the tails of the stones were engaged and held in position by the uprights. The floor was not examined except for the small areas which it was necessary to disturb in order to reset the insecure uprights. A few bone fragments were found, probably not ancient (Appendix II, No. 2), but no pottery.

The chamber was probably covered by a single stone resting directly on Nos. 9, 12 and 15, and, with the aid of wedges or walling, on Nos. 10, 11, 13 and 14.

The Western Chamber

Work here (Figs. 3 and 5) was confined to the examination of part of the floor and to rebuilding the dry walling between stones 20 and 21. This was modern and in a bad condition, but after excavation the two bottom courses of the old work were found in position. All the rest of the walling in this chamber was modern and in a sound state, but had to be heightened in places.

The area north and west of stone 21 was partly examined for evidence to show whether the gap between it and stone No. 1 was formerly occupied by another upright or whether there was an entrance here to another chamber. It seems certain that the first hypothesis was correct, and one or two of the packing stones probably remain in spite of much disturbance when the forced entrance was made. A quite definite statement bearing on this point is made in a book entitled Te Conway and the Stereoscope, published in 1860, where the following words appear on p. 173: "Some years ago the compartment under the stone was converted into a stable, by clearing out the side of the carnedd to the west, throwing down the end stone, and fitting in a framed window. A door was also provided, and a stone manger. All these have since been removed."

In front of stone 21, at 10 in. from its foot, was found a pocket of clean but disturbed yellow clay, 6 in. in diameter and 12 in. deep. A few inches east of this pocket was a smaller one, 2½ in. in diameter, placed at a raking angle to the larger one and to the stone behind it. Perhaps it may have held a wooden strut during the erection of the chamber. The floor near the modern entrance had been considerably disturbed, and time allowed only of a partial examination. A rough paving was found beneath recent accumulations of soil and stones, and small objects of modern origin, such as fragments of glazed pottery, found below it proved that it dated from the stable period; 6 in. below the top of this paving was found clean but relaid yellow clay. An iron ring and the post stone of the stable door were found on the south side of the entrance.

Stone No. 1 appeared to have been twisted round in order to give more room for the window; it was left as found. The relative levels of the ground surface within and without the chamber were not definitely ascertained. The false opening was retained and steps made in the approach to it to enable visitors to examine the interior of the monument without having occasion to climb up or down the walls.

It seemed probable that the cover stone and several of the supporters had been obtained from an out-cropping crag a few yards to the south-west of the monument. Mr. Howel Williams, M.Se., was kind enough to examine the stones, and his report confirms the supposition (Appendix III). Mr. Williams states in less Lm language that the stone is "a fine volcanic dust of quite unique type, containing a green mineral not found elsewhere," which "is full of beautiful twinkling spots due to radioactive inclusions—remarkably rare and pretty."

All About History Books

Abbot John Whethamstede’s Chronicle of the Abbey of St Albans

Abbot John Whethamstede's Register aka Chronicle of his second term at the Abbey of St Albans, 1451-1461, is a remarkable text that describes his first-hand experience of the beginning of the Wars of the Roses including the First and Second Battles of St Albans, 1455 and 1461, respectively, their cause, and their consequences, not least on the Abbey itself. His text also includes Loveday, Blore Heath, Northampton, the Act of Accord, Wakefield, and Towton, and ends with the Coronation of King Edward IV. In addition to the events of the Wars of the Roses, Abbot John, or his scribes who wrote the Chronicle, include details in the life of the Abbey such as charters, letters, land exchanges, visits by legates, and disputes, which provide a rich insight into the day-to-day life of the Abbey, and the challenges faced by its Abbot.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

Treatment

The cover stone was found to be badly cracked along several of the natural perpendicular lines of cleavage, and showed a tendency to flake on the underside. It has now been given additional support by the insertion of a light rolled-steel joist, the ends of which are buried in the mound.

In addition to the resetting of certain uprights and rebuilding of sections of the dry walling already noted, in certain places where the old walling, although still in position, showed signs of weakness, cement was tamped in between the stones, but kept well back from the wall face. Where it was necessary to replace lost sections the walls were built with thicker courses than in the old work. Where new walling was built above old, a line of small pits was drilled in the face of the lowest course of the added masonry, isolated new stones being marked by a single pit. It will therefore be possible for future generations to distinguish the new work from the old.

RESULTs AND CONCLUSIONS. Apart from the recovery of the fragments of dateable pottery, the important results of the exploration are:— (a) The proof that the monument was completely closed within a short period after it was first set up, and that its reopening may not have been contemplated: (b) The fact that the area between the horns of the false entrance was from the first occupied by the material of the mound; and (c) the evidence obtained as to the structural devices employed by the builders.

The deliberate inclination of the majority of the uprights in the passage is interesting and is paralleled in Ireland at the Dowth tumulus. It may be merely structural and intended to reduce the span of the corbelled roof which covered the southern part of the passage, whereas the northern end, where the stones are upright, was probably roofed by one or more slabs. At New Grange [Map], where the passage is 62 ft. in length, it is narrowed by a similar device at 14 ft. from the entrance, for a distance of 6 ft., and the rock-cut tombs of approximately the same period in the South of France near Arles, and elsewhere in the Mediterranean area, have their sides inclined inwards. Some British and Continental dolmens also have the supporters of their main capstone similarly out of the perpendicular, an insecure and unnatural method of construction which implies some strong traditional motive. In any case, however, the greater width of the northern portion of the Capel Garmon passage suggests that it was used as a vestibule, while the existence of a patch of burnt clay and a "post-hole," together with the fragments of pottery, all bear out the hypothesis that it was not solely intended as the means of access to the tomb, but may have served as the ante-chamber which is found in other funeral monuments of the period, and which is perhaps usually represented in long barrows by the space between the spreading horns of the entrance—a hace which at Capel Garmon was always occupied by the covering mound of stones.

Note 1. George Coffey, New Grange, Dublin, 1912, fig. 30.

There are several parallels to the use of the white quartz stones, which seem to have been scattered at the foot of the internal wall. Water-worn and deliberately broken pebbles of white quartz have been found by the writer at the Bryn Celli Ddu cairn in Anglesey and around the grottes near Arles, which were also in use during the Beaker period and in some of which were found beds of quartz;1 while in a chambered cairn at Achnachree, Argyllshire, pebbles of quartz were found on a ledge.2

Note 1. L. A. Constans, Arles Antique, Chap. 1, pars. 1 and 2.

Note 2. "Cat. Nat. Mus. Antiq.," Soc. Ant. Scot., 1892, p. 180.

The probability that stone 9 was artificially dressed is increased by the recent discovery that most of the uprights of the chamber and passage of the Bryn Celli Ddu cairn have been extensively worked.

There are parallels to the use of the false entrance, e.g., Belas Knap [Map], Rodmarton and West Tump [Map] in the Cotswolds.1

Note 1. O. G. S. Crawford, Long Barrows of the Cotswolds, and Ordnance Survey, Professional Papers, New Series, 6, Part I, p. 4.

When Dr. Thurnam found fragments of "Beaker" and "Neolithic" pottery in the undisturbed chamber of the West Kennet long barrow he was careful to note that the fragments had been deposited in separate heaps and did not represent complete vessels.1 It is possible that the same practice was followed at Capel Garmon.

Note 1. Archæologia, XXVIII, p. 417. [Note. Thurnam's article on West Kennet Long Barrow is in Archæologia Volume 38.]

All About History Books

Anne Boleyn. Her Life as told by Lancelot de Carle's 1536 Letter.

In 1536, two weeks after the execution of Anne Boleyn, her brother George and four others, Lancelot du Carle, wrote an extraordinary letter that described Anne's life, and her trial and execution, to which he was a witness. This book presents a new translation of that letter, with additional material from other contemporary sources such as Letters, Hall's and Wriothesley's Chronicles, the pamphlets of Wynkyn the Worde, the Memorial of George Constantyne, the Portuguese Letter and the Baga de Secrets, all of which are provided in Appendices.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

The association of the two types of pottery, apparently deposited at the same time, suggests that some of the wares which hitherto have been termed Neolithic may have to be assigned to a later date.

The Capel Garmon monument must represent a late type in the development of the megalithic tomb, when the elaborate form of construction had already become traditional. The late date is also borne out by the "Beaker" pottery as Dr. Fox points out in his report.

Appendix I. Note on the Flint and Pottery Artifacts. By Dr. Cyril Fox, F.S.A.

Flint.—One chip of grey flint, humanly struck.

Pottery.—Six fragments, A-F.

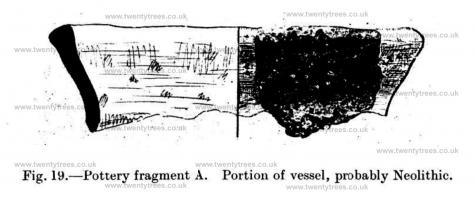

A. Late Neolithic.

A portion, undecorated, of the rim of a vessel. The fragment measures 5 X 4.5 cm. The rim is thickened and flattish (10 mm.), elsewhere the wall is 5-6 mm. in thickness. The ware is coarse, well-baked, greyish-black in colour, and deeply pitted—probably as a result of the decay of certain elements of the paste.1 The curvature suggests that the rim diameter was about 15 ecm., and, to judge by the plane of the inner edge of the rim, the vessel was wide-mouthed. The fragment (were it wheel-made) would be large enough to enable the form of the upper part of the vessel to be determined with certainty; being hand-made and wrought with no great care, probability is all that can be claimed for the accompanying reconstruction (Fig. 19). The fragment is probably Neolithic. Mr. O. G. S. Crawford, to whom I sent the sherd, concurs in this guarded opinion.

Note. Not, in this case, burnt-out grass or straw; cf. late Romano-British pottery, from Huntdliffe, Yorks, J.R.S., II, p. 228.

B-F. Transitional or Early Bronze Age

The remaining fragments, five in number, ranging in size from 5 x 2.5 cm. to 2 x 1.5 cm, can be identified with certainty as beaker pottery. Two vess:ls are represented, one by three, the other by two fragments. The wares are of fair quality, the ornament characteristic and, In one case at least, very carefully wrought. I suggest that, considering their provenance, necessarily far removed from areas first occupied by the makers of this class of pottery in Britain, they may be held to date in the middle of the Beaker phase of culture in this country, circa 1800-1700 B.C.

The presence of these fragments in the passage of Capel Garmon shows that this tomb was in use early in the second millennium B.C., and that groups or families of the Beaker folk were living in the district. It is probable that these invaders controlled the countryside, and found it desirable, for political reasons, to utilise the burial places of the chiefs whom they displaced; usually, as is well known, they raised round barrows over their dead. Beaker pottery has been found elsewhere in Britain in two megalithic chambered tombs, the Tinkins Wood long cairn [Map], St. Nicholas, Glamorgan (Arch. Camb., 1916, p. 250), and the West Kennet long barrow [Map], Wiltshire (Devizes Museum), and similar conclusions may be drawn from the presence of this pottery in these burial-places.

The results of Mr. Hemp's investigation show what valuable results may be obtained from the scientific examination of megalithic tombs, even though they have been rifled and dug over in modern times.

Fragment B is a piece of the waist of a beaker, Abercromby type A or type C; it shows a plain zone bounded by notched and impressed ornament. C and D show the same ornament, and are almost certainly fragments derived from the ornamented zone immediately above the waist. I have reconstructed the central portion of the vessel on this assumption, reproducing fragments Band C (Fig. 20). The risk of error in the reconstruction of the ornament is in any case small, because it is usual for the zones of ornament above and below the waist to be identical. Fragment C is large enough to give the approximate diameter of the vessel (11.5 cm.) at this point. The oval impressions bear a certain resemblance to the "maggot" pattern on Neolithic pottery, and their form may be infuenced by the native ornament.

The design on our beaker was evidently built up of closely spaced and carefully wrought decoration. I suspect that the appearance of the complete beaker was not unlike an example from Monsal Dale, Derby, figured by Abercromby,1 but it is by no means certain that the recovery of the central zones gives us the full range of the ornament employed on the vessel. The paste of the fragments is of fair quality; the walls (7-8 mm.) are thicker than those of the best beakers. The colour is pink and yellow externally, yellow internally, and the core is greyish —quite normal characteristics for this class of ware.

Note 1.Bronze Age Pottery, Vol. I, pl. X, Fig. 102.

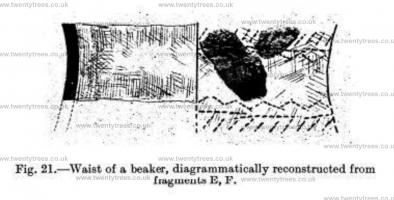

Fragments E and F formed part of a well-baked and fairly thin-walled (6 mm.) vessel; they are pinkish-yellow externally and internally, the core being greyish-black. The larger fragment1 with concave external curvature, I take to be the undecorated zone at the waist of the beaker, with a portion of the ornament (impressed with a notched quadrant) which defined it. The other fragment shows similar impressions and probably belongs to the same zone of ornament. These two fragments thus give us the elements of the design at the waist of the beaker, and Fig. 21 presents a reconstruction of the central zone. The notched impression is very thin, 1 mm. in diameter; the pattern 18 very simple, and its elements commonly occur on British beakers.

Note 1. Fractured, as the figure shows.

All About History Books

Jean de Waurin's Chronicle of England Volume 6 Books 3-6: The Wars of the Roses

Jean de Waurin was a French Chronicler, from the Artois region, who was born around 1400, and died around 1474. Waurin’s Chronicle of England, Volume 6, covering the period 1450 to 1471, from which we have selected and translated Chapters relating to the Wars of the Roses, provides a vivid, original, contemporary description of key events some of which he witnessed first-hand, some of which he was told by the key people involved with whom Waurin had a personal relationship.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

Appendix II. Report on the Bones, By Dr. W. L. H. Duckworth

1. Metacarpals and (?) part of tibia, but neither are human—more likely young sheep.

2. Non-human mammalian bones—animal about size of a pony or a small cow—almost certainly part of a femur in one instance,

3. (?) human epiphysis—regret cannot identify.

4. One definite human skull fragment.

5. (?) human skull fragments; as some are a little above the average for thickness, probably a male is represented. I am almost certain of these being human.

No. 1 found in the body of the mound behind stone 29.

Nos. 2-5 in disturbed surface soil in the passage and chambers.

Appendix III. Report on the Stones. By Howel Williams, M.Sc

All the slabs employed in the construction are of cleaved volcanic dust of rhyolithic character, a rock which occurs abundantly in the vicinity. The presence in the capstone of microscopically small flakes of green, chloritised biotite with pleochroic halos, resulting from radioactive inclusions, enables the exact location of its source, for nowhere save in the crag immediately to the south west of the cairn have similar flakes been observed in the rhyolithic tuffs. The cleavage is such as to render the fashioning of large, thick slabs an easy process. Weathering is insignificant.