Text this colour is a link for Members only. Support us by becoming a Member for only £3 a month by joining our 'Buy Me A Coffee page'; Membership gives you access to all content and removes ads.

Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Volume 51 1929 is in Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.

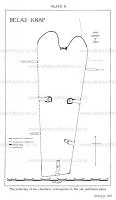

Belas Knap Long Barrow [Map], Gloucestershire. Report by W. J. Hemp 1929, Vol. 51, 261-272.

BELAS KNAP LONG BARROW, GLOUCESTERSHIRE, Report by W. J. HEMP, F.S.A.

The early printed records of the excavations in Belas Knap have been admirably summarized by Mr O. G. S. Crawford in The Long Barrows of the Cotswolds and it is sufficient merely to refer to that book, in which full details and references are given.

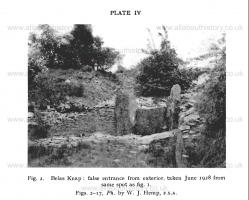

Unfortunately however, much disturbance of the site occurred during the latter part of the 1gth century of which no record has been preserved; some of it undertaken with the best of intentions, other merely mischievous. Under the first heading is a considerable amount of preservation carried out by the late Mrs Dent of Sudeley Castle. This included wholesale rebuilding of the dry-walling, which was carried out with such skill and thoroughness about half a century or more ago that in the overgrown and decayed condition into which it had fallen of recent years it had become difficult to distinguish between the old and the new work (figs. 1 and 2). It is regrettable that no record has been preserved of the discoveries which were made when this was being done, apparently under no sort of supervision.

Some of the men employed were still living in 1928 and their recollections as then noted down are here placed on record.

Charles Yiend of Winchcombe, aged 83, was a man of much intelligence and had always been interested in Belas Knap and the other antiquities of the district. He well remembered the barrow before it was violated in 1863 and was accustomed to sit upon it to eat his dinner. He was employed on the excavations, and confirmed from his own memory the fact that before they were undertaken, the mound was completely covered with turf and that there was nothing to indicate the existence of the false entrance or the horns flanking it on either side, the area between them being completely filled with earth and stones. The lintel stone was broken in pieces in the course of its removal and he himself chose and fetched from the wood the stone which now occupies its place. This was then larger however, as it has been mischievously thrown down at least twice and part of it has been broken away.

William Aston of Winchcombe, who was sent by Squire Swinburne to work on the barrow by himself between 40 and 50 years ago, found some bones; more men were then employed—they found the internal wall, followed it and discovered a chamber. Bones of six or seven bodies were up against a wall; only bones were found.

Albert Potter of Winchcombe was employed on the mound by Mrs Dent about 1890. He came across a large horizontal stone which he found to be supported on uprights and covering a chamber. He lifted it, and found a single skeleton 'sitting in a corner with its elbows on its knees'. By Mrs Dent's orders the bones were left as found, the chamber closed again and the capstone once more covered with rubble.

The above accounts are summarized from notes taken down from the men on the spot. The information given by Aston and Potter may refer to the same series of excavations, in spite of the discrepancies. Both men agreed that they were working near the head of the mound and there seemed a strong probability that there was a fifth chamber in the east side, north of C, awaiting careful exploration, and if so that it was likely to be balanced by a fellow in the west side.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

The barrow was transferred to the guardianship of H.M. Office of Works by the late Col. Rhodes of Brockhampton, and the task of its preservation was taken in hand in the summer of 1928. The first season's work, during which a foreman and two labourers were employed, consisted firstly in cutting down the trees and brushwood which almost completely covered the monument; secondly, in removing their stumps and roots—a long and difficult task, calling for much care lest structural details should be damaged or destroyed—about half the stumps were actually removed; thirdly, in the preser- vation of the original dry walling at the portal or false entrance, where it still remained intact to a maximum height of about 2 feet 6 inches.

It had been assumed that all the walling which remained visible both here and at the entrances to the three chambers was original, but on examination it became evident that not only had the whole of the walling of the chambers been rebuilt in the 1gth century, but also a considerable amount of that flanking the portal (fig. 2).

Close observation and comparison with early photo- graphs and drawings made it possible to determine accurately the junction of the new work with the old. Creepers and shrubs had secured a footing between the stones in many places, and stretches of the wall were in imminent danger of collapse from this cause as well as from the decay of some of the original stones. Quite recent falls emphasized the dangerous condition.

There were two possible lines of treatment: the first completely to rebury the walls which had never been fully exposed from the day the monument was completed until 1863; the second, to secure them as found in 1928 in such a way that they could remain visible for the benefit of students as a unique example of the particular type of ceremonial building and craftsmanship which they represented. The second course was adopted, the object kept in view throughout the work was that when it was completed the monument should present an appearance approximating to that which it must have borne at the time when the funeral ceremonies were carried out which controlled and determined its design and construction.

This policy necessarily involved a certain amount of reconstruction, but such a departure from the usual principles governing the work carried out by the Ancient Monuments Department of H.M. Office of Works in the treatment of medieval buildings was felt to be justified in the particular circumstance of this case.

It was considered essential that the preservation of the ancient work should be carried out in such a way as to leave no visible traces, and the method adopted was first to shore up the face of the old walling with planking and then to expose the backs of the stones and secure them in cement. This was done and so much of the 19th century work as was in a satisfactory condition was also secured, while entirely new walling was added where its presence was necessary to hold up the mound. It isto be hoped that on the completion of the work the line of junction of the new work with the old will be clearly marked, perhaps by drilling a series of small pits on the faces of the new stones, as was done under somewhat similar conditions at the Capel Garmon chambered caim [Map].

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

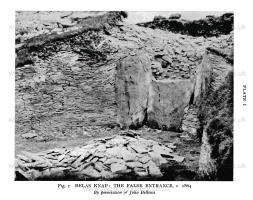

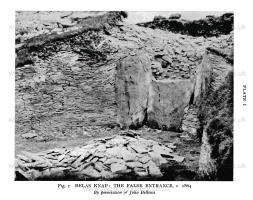

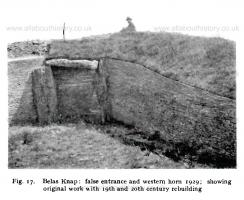

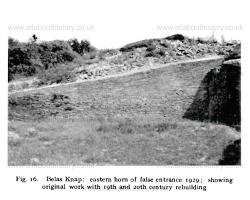

The original appearance of the portal had been recorded by a series of photographs and drawings contemporary with the early excavations, and from these it was clear that, in addition to the two uprights and the blocking stone between them, there had been a lintel resting on the uprights, the interval between the underside of the lintel and the upper edge of the blocking stone, and the gap between the latter and the western upright being filled with dry walling.

When H.M. Office of Works assumed the guardianship of the monument a large stone was lying at the foot of the uprights and it was assumed that this was the fallen lintel. As recorded above however, the original lintel was either found in a broken condition in 1863 or destroyed soon after discovery and had been replaced by the fallen stone, which had subsequently been mischievously thrown down and set up again, only to be displaced a second time. This stone is now again in position, firmly anchored by clamps of delta metal and with new walling beneath it serving to retain the replaced material behind it, as well as to illustrate the original construction.

The evidence for the present arrangement is to be found in two illustrations reproduced from Mr Crawford's book. One, a drawing (see p. 272), claims to represent the original appearance of the 'Portal' and is checked by the photograph (figure 1), taken shortly after the uncovering in 1866.

The discrepancy in the height of the two uprights, the western one being 5 in. higher than the eastern, as well as the shoulder cut one foot four inches below the top of the western one, in which the lintel now rests, suggests that the drawing, which was almost necessarily drawn from memory, is in error in showing the lintel resting on the top of both pillars. The photograph confirms the suspicion as it shows the dark line of the original skin of turf right down upon the western upright, in contrast with its relation to the eastern one which it would have cleared by about two feet.

On the other hand the drawing is in agreement with the known facts in showing the turf as completely covering the lintel, which it could not have done had the latter rested on the top of the upright.

The drawing depicts the walling filling the interval between lintel and blocking stone but not that between the latter and the western upright. Fortunately this omission is made good by the photograph. The drawing however does distinguish between the carefully built walling below the lintel and the section of the body of the mound shown above it.

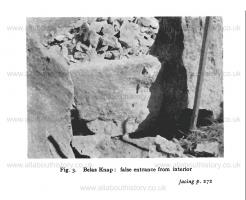

The walling was repaired during the absence of the writer, but he saw the excavation behind the blocking stone and both supporters when it was at its maximum (fig. 3). The area immediately behind the 'entrance' had been cleared by the earlier excavators down to ground level2 and partly refilled; on either side however the original material of the cairn remained intact, consisting of large stones for the most part laid horizontally, the largest resting directly on the ground. There was nothing to suggest the existence of a passage, indeed fig. 3 shows one large stone of the filling in situ in such a position that it must have projected into one had it existed, and, of course, with such a plan it is scarcely conceivable that there should have been any central passage.

Note 2. As indicated in the plan (fig. 17) published by Dr Thumam in his article on British and Gaulish skulls in the Memoirs of the Anthropological Society, vol. 1, p. 474.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

The body of the cairn and the dry walling of the horns interlocked and had undoubtedly been built together (fig. 11).

As a result of the 19th century excavations a deep trench had been left open down the centre of the cairn, running from the back of the portal to meet another trench cut down to ground level at right angles to it and connecting the two exposed chambers C and D.

The débris resulting from these excavations and from the clearance of the area between the horns had been used in two ways; from the larger stones was built the wall enclosing the monument (and probably others in the neighbourhood), while the remaining mass of material was spread more or less regularly against the inner face of this wall, covering the base of the cairn and disguising its contours. A particularly large deposit was placed in the northeast corner of the enclosure and it is likely that the bulk of this was obtained from between the horns.

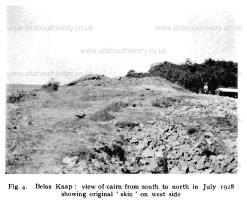

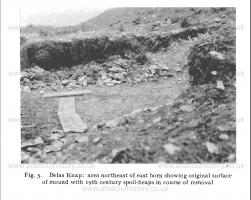

With the aid of a series of trial trenches and the fortunate survival of a very few patches of theoriginal 'skin' of soil and turf which had completely covered the mound up to the year 1863 (fig. 4), it was possible to establish the line of its original contours; the restoration of these at the north end was begun by the use of the material in the northeast corner. With a little experience it was possible to determine with certainty the line of junction between the original mound and the débris placed upon it. (Fig. 5).

The Internal Wall

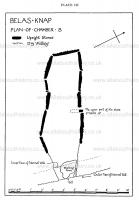

Concurrently with the above work and during the writer's visits to the site the course of the internal wall was established at all the critical points, particularly at the south end, where the resulting plan differs materially from that published by the original excavators, not only in the direction and position of the wall, but also in the shape of the chamber E. The extreme southwest corner had been completely ploughed away as it projected beyond the wall into the field.

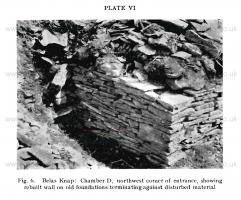

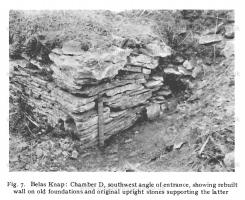

It was found that all the visible dry walling at the entrances and passages leading to the three fully exposed chambers (C, D, and E) had been rebuilt on the original foundations in the 19th century, but the bottom course or courses remained to indicate its true position. Where- ever it had been built to a height of more than a few inches the pressure of the mound within it had forced the upper courses out of position (figs. 6-8) and its exact location was often a matter of difficulty, particularly where the materials had been disturbed by the trenches of the earlier explorers.

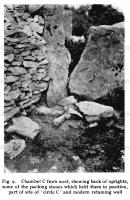

Modern accumulations of stones and tree growths were removed from the two principal chambers (c, and p) and also from the area between them, where the original excavators recorded the discovery of a ' circle of stones' (F) accompanied by a deposit of ashes. No trace of these stones were found and it was certain that they could not have been upright stones planted in the ground, as the original surface of this was found to been disturbed and to consist chiefly of rock covered by a very thin layer of stiff yellow clay. (Fig. 9).

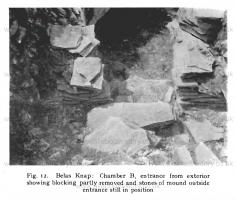

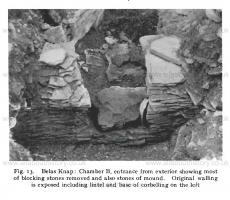

Chamber B was the first part of the monument to be explored, its capstone being discovered and removed in 1863. Fortunately tlie contents were examined on that occasion, and the blocking of the entrance passage was left undisturbed until it was tampered with a few weeks before the work on the monument was undertaken, and the roof of the entrance destroyed. The writer completed the clearance and by so doing obtained evidence that the passage had originally been roofed by corbelling; that it had been deliberately and carefully blocked; and that the internal wall had been continued across the entrance as a low sill three courses high. (Figs. 10, 12-13). Outside and along the foot of this wall at ground level, here as elsewhere, were placed single bones and teeth of animals a few inches apart.

The body of the mound outside this entrance was undisturbed and consisted of stones very carefully placed so as to support the wall and prevent its spreading, laid flat and raking upwards. (Fig.12). A similar arrangement was found on either side of the entrances to chambers C and D.

From the evidence obtained it is certain that the passage to the chamber was completed and roofed and the internal wall left exposed for some distance on either side of the entrance (and presumably all round the monument); also that at a subsequent date, although after a very short interval, as there was not the slightest evidence of silting, the passage and entrance were carefully blocked, bones and teeth placed along the base of the wall, and the mound completed by carefully laid layers of stones covering the face of the wall in such a way as to obliterate all traces of the entrance.

The blocking extended about one foot six inches into the passage and included one large stone which has been left as found, together with two smaller stones set on edge beside it which served to wedge it in position. The blocking, together with the sides of the entrance passage, formed the 'semicircle of rough dry walling' as described by the explorers of 1863, who found that the chamber contained four human bodies, two male and two female, as well as ' bones and tusks of boars, a bone scoop, four pieces of rough sun-baked pottery and a few flints*. It is probable that the chamber was floored by small irregular blocks of stone. Nearly all had been removed, but a few still remain partly covered by and projecting from the face of the wall of the chamber.

The design of this 'cell' calls for some remark. As recorded above, the chamber itself was roofed by one or more slabs, and the entrance passage by corbelling. This distinction is emphasized by the plan and also by the method of building the walls. There are in fact three elements, as the entrance passage with its sides of small walling gathered over to form a corbelled roof, leads to a chamber having its side walls formed of upright slabs crowned by horizontal walling, coarser than that of the passage; the chamber is subdivided by having one of these uprights on the north side set at right angles to the general line of the wall, the upper part projecting ten inches into the passage. East of this point the chamber widens several inches before narrowing to the passage.

This design suggests some ceremonial use, perhaps the outer part of the chamber may have served as an ante- chamber and been the site of purifying fires.3

Note 3. See Archæologia Cambrensis, 7th series, vii, 24-25, where is a description of an arrangement which may be analogous at the Capel Garmon chambered-cairn.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

All About History Books

The Deeds of King Henry V, or in Latin Henrici Quinti, Angliæ Regis, Gesta, is a first-hand account of the Agincourt Campaign, and subsequent events to his death in 1422. The author of the first part was a Chaplain in King Henry's retinue who was present from King Henry's departure at Southampton in 1415, at the siege of Harfleur, the battle of Agincourt, and the celebrations on King Henry's return to London. The second part, by another writer, relates the events that took place including the negotiations at Troye, Henry's marriage and his death in 1422.

Available at Amazon as eBook or Paperback.

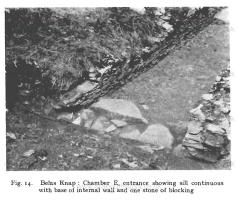

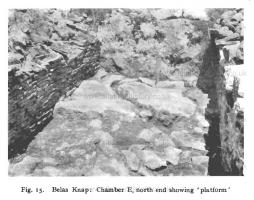

Chamber E was cleared of modern accumulations of stones and rubbish. The lowest course of the internal wall was found still in situ and ran across the entrance without a break. (Fig.14). The far end was floored by large stones, the upper surface of which was two or three inches above the general level of the floor of the rest of the chamber (fig. 15), which was undisturbed. That the plat- form thus formed at the end is an original feature is proved by the dry walling on either side, of which the two lowest courses are original and are stepped up to and built upon the stones.

The plan differs materially from that published in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries (1866, p. 276). The chamber is—and must always have been—a 'simple rectangle', the only distinguishing feature being the end platform referred to above and the newly revealed foundation of the sill, which was continuous with the internal wall as in the case of chamber B. A large flat stone set on clay and found in sit immediately behind the sill suggests that, like B, chamber E was closed by a carefully built blocking.

The explorers discovered the chamber in 1865. It was apparently perfect and untouched. Portions of a human skull, some teeth, and a deposit of animal bones, probably a wild boar, were met with in working down to it. It was walled all round, covered with three large horizontal stones, each about three feet square, but contained pieces of broken stones ... The very frag- mentary skull and the boars' bones found at the South end are said to present marks of cremation'. These bones seem to have been a secondary deposit.

The side walls were subsequently rebuilt upon the original foundations, except on either side of the entrance where false corners were made disguising the continuity of the internal wall with the sill.

The contrast between the designs of the different chambers is very marked.

B has already been described, with its varied walling and irregular plan.

C and D have well-marked chambers formed by large and comparatively tall uprights and were covered by corbelled roofs and approached by straight passages.

The sides of E are perfectly straight, parallel walls of small dry-built masonry—the bottom courses remain to confirm the accuracy of the rebuilding. It is terminated by a single upright, and at the end is a platform formed of slabs of stone; this platform may be comparable with the similarly-placed large slab of stone found in each of the side chambers in the great cairn of Maeshowe in Orkney.

Thanks are due to Dr J. Wilfrid Jackson for his report on the animal remains found.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.