Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Conwy Castle is in Conwy [Map], Castles in Carnarfonshire.

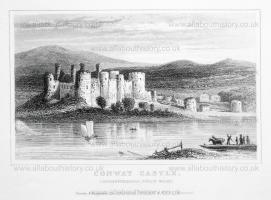

Conwy Castle [Map]. Dugdale's England and Wales.

The Welsh Castles and Towns of Edward I comprise a number of castles, some with associated planned towns, commissioned as a means of containing the Welsh. They included, from east to west, Flint Castle [Map], Rhuddlan [Map], Conwy Castle [Map], Beaumaris Castle [Map], Caernarfon Castle [Map], Harlech Castle [Map] and Aberystwyth Castle [Map]. Those not on the coast include Chirk Castle [Map], Denbigh Castle and Town Walls [Map] and Builth Castle [Map]. Arguably, Holt Castle [Map] and Criccieth Castle [Map] should be included.

The Large Court in Conwy Castle [Map]. S Crowther.

Conwy Castle [Map] Banqueting Hall. W Banks & Son.

In 1294 William Beauchamp 9th Earl Warwick (age 57) raised the siege of Conwy Castle [Map].

Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough. When the king heard of these things, he immediately gathered his army and turned aside there, sending letters to his brother Lord Edmund and to the Earl of Lincoln1, who at that time were in the port of Portsmouth with many thousands of armed men, prepared to cross over into Gascony, ordering them to return to him in Wales with all haste. Upon hearing this, they hurried to him and remained there until nearly the middle of Lent. Now it happened that on the Feast of Saint Martin [11th November 1294] in winter, while the Earl of Lincoln was hastening before our king to his own castle of Denbigh, hoping perhaps to save it. as he believed, he was intercepted by his own Welsh men, he had many possessions and castles there, who engaged him in a fierce battle. These Welshmen of his ultimately prevailed against him, and after many on both sides had been killed, they finally forced him to flee with a few men, although he had fought bravely for a long time. Our king also, after crossing the river Conway, while making his way to the castle [Map], was not followed by the whole army. And so, as the sea waters and sudden tides overflowed, he was besieged by the Welsh for some time. Thus separated from his men and cut off, he suffered for a short time both hunger and thirst, drinking water mixed with honey and not eating bread to satisfaction; for the Welsh had overtaken his wagons, seized his supplies, and slaughtered the men they could catch. When they had only a small amount of wine, barely a flask's2 worth, which they had decided to preserve for the king, the king refused it and said: "In necessity all things ought to be held in common, and we shall all endure one and the same meagre fare until God Himself from on high looks down upon us. I will not be preferred to you in food, since I am the very cause and origin of this hardship." But soon after, God Almighty visited them with mercy: the waters receded, the whole army came to the king, and the Welsh were turned to flight. After many events and various battles, the Welsh were so harassed and pressed that, after many messengers were sent and returned, Madog himself and his followers were admitted to the king's peace, on the condition, however, that he would pursue and capture the other, namely Morgan, and hand him over to the royal prison within a set time. This agreement he kept and fulfilled, and so he obtained full peace. Many nobles from all over Wales were taken as hostages and sent to various castles in England to be held there until the king gave further orders; and they remained in those places until nearly the end of the war in Scotland. In the same year, a severe famine afflicted England, and many thousands of the poor died. A quarter of wheat was sold for sixteen shillings, and often for twenty.

Quæ cum audisset rex, mox congregato exercitu declinavit ibidem, missisque literis ad dominum Edmundum fratrem suum et comitem Lincolniæ, qui tunc temporis in portu de Portesmuth cum multis millibus armatorum parati fuerant in Vasconiam transfretare, ut ad eum in Walliam cum omni festinatione redirent; qui cum audissent talia properabant ad eum, et manserunt ibidem usque and defeat fere ad medium Quadragesimæ. Contigit autem quod die sancti Martini in hyeme dum idem comes Lincolniæ ad castrum suum de Tynebech ante regem nostrum festinaret, si forte illud salvare posset, sicut credidit, obviatus est ab hominibus suis propriis Wallensibus, habet enim ibidem multas possessiones et castra, qui quidem Wallenses sui commisso cum eo gravi prœlio prævaluerunts adversus eum, et interfectis hinc inde multis, ipsum tandem, cum jam diu strenue militasset, in fugam cum paucis converterunt. Rex etiam noster, transito flumine de Conway, dum ad castrum declinaret non est eum secutus totus exercitus, unde superabundantibus aquis maris et fluctuum subitorum obsessus est a Wallensibus per tempus aliquod. Sic separatus a suis et exclusus passusque est ad tempus modicum et famem et sitim, bibitque aquam cum melle mixtam et panem in saturitate non comedit; præoccupaverant enim Wallenses quadrigas suas, et victualibus acceptis et ablatis, homines quos poterant detruncabant. Cumque haberent modicum vini, vix unius lagenæ costrellum, quod pro rege salvare decreverant, non adquievit ipse rex, sed ait, "Omnia in necessitate debent esse communia, et omnes unam et similem dietam patiemur quousque respiciat nos ipse Deus ab alto, nec præficiar vobis in esu qui coarctationis istius origo et causa sum;" cito autem post visitavit Deus omnipotens eos, et decrescentibus aquis, venit ad regem exercitus totus et ipsi Wallenses in fugam versi sunt. Post multos autem eventus et conflictus varios in tantum Wallenses sunt agitati et astricti, quod missis et remissis nuntiis ipse Maddoch cum suis ad pacem regis admissus est, sub conditione tamen tali quod alterum scilicet Morgan prosequeretur et caperet, et infra certum tempus regio carceri manciparet. Quod quidem pactum tenuit et fecit, et plenam pacem adeptus est; acceptique sunt obsides multi de nobilioribus and gives totius Walliæ, et missi sunt in Angliam ad diversa castra ut custodirentur in eis usque ad jussionem regis, manseruntque in eisdem usque ad guerram Scotia fere finitam. Eodem anno fames valida Angliam afflixit et moriebantur pauperum multa millia, vendebatur enim quarterium frumenti pro XVI solidis et multotiens pro XX.

Note 1. Henry de Lacy, third earl of Lincoln, succeeded his father in 1257. In the preceding year, having espoused Margaret, daughter and co-heir of William de Longespee, (son of William de Longespee, Earl of Salisbury,) he became, jure uxoris i.e. by right of his wife, Earl of Salisbury.

Note 2. The capacity of the 'lagena' i.e. flask is thus given in an Assize of David, King of Scotland, concerning weights and measures. The lagena should be capable of containing twelve pounds of water, four pounds of sea-water, four of stagnant water, and four of pure. Its depth should be six inches and a-half, its breadth at the foot should be eight inches and a-half, taking the thickness of the wood on either side; at the higher extremity it should measure in circumference twenty-seven inches, and at the lower twenty-three. The lagena was also a dry measure, as we read of it in connection with corn and butter.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

In December 1294 Madog ap Llywelyn besieged King of England in Conwy Castle [Map] for three months.

On 12th August 1399 King Richard II of England (age 32) negotiated with Henry Percy 1st Earl of Northumberland (age 57) at Conwy Castle [Map].

The Deposition of King Richard II. 12th August 1399. Then the earl went on board a vessel and crossed the water. He found King Richard, and the Earl of Salisbury (age 49) with him, as well as the Bishop of Carlisle. He said to the king,p "Sire, Duke Henry hath sent me hither to the end that an agreement should be made between you, and that you should be good friends for the time to come, — If it be your pleasure, Sire, and I may be heard, I will deliver to you his message, and conceal nothing of the truth; — If you will be a good judge and true, and will bring up all those whom I shall here name to you, by a certain day, for the ends of justice; listen to the parliament which you shall lawfully cause to be held between you at Westminster, and restore him to be chief judge of England, as the duke his fatherq and all his ancestors had been for more than an hundred years. I will tell you the names of those who shall await the trial. May it please you, Sire, it is time they should."

Note p. We are here supplied with some additional matter from the MS. Ambassades. Huntingdon, by command of the duke, sent one of his retinue after Northumberland with two letters, one for Northumberland, the other for the king. When he appeared before the king with seven attendants, he was asked by him, if he had not met his brother on the road? "Yes, Sire," he answered," and here is a letter he gave me for you." The king looked at the letter and the seal, and saw that it was the seal of his brother; then he opened the letter and read it. All that it contained was this, "My very dear Lord, I commend me to you: and you will believe the earl in every thing that he shall say to you. For I found the duke at my city of Chester, who has a great desire to have a good peace and agreement with you, and has kept me to attend upon him till he shall know your pleasure."2 When the king had read this letter, he turned to Northumberland, and said, "Now tell me what message you bring." To which the earl replied, "My very dear Lord, the Duke of Lancaster hath sent me to you, to tell you that what he most wishes for in this world is to have peace and agreement with you; and he greatly repents with all his heart of the displeasure that he hath caused you now and at other times; and asks nothing of you in this living world, save that it may please you to account him your cousin and friend; and that it may please you only to let him have his land; and that he may be chief judge of England, as his father and his predecessors have been, and that all other things of time past may be put in oblivion between you two; for which purpose he hath chosen umpires (juges) for yourself and for him, that is to say, the Bishop of Carlisle, the Earl of Salisbury, Maudelain, and the Earl of Westmorland; and charges them with the agreement that is between you and him. Give me an answer, if you please; for all the greatest lords of England and the commons are of this opinion." On which the king desired him to withdraw a little, and he should have an answer soon.1

The latter part of this speech contains an important variation from the metrical history, worthy of the artifice of the earl; but the opposite account of our eye-witness, confirmed in Richard's subsequent address to his friends, is doubtless the true representation. The writer of MS. Ambassades might be at this time at Chester; but admitting that he had been in the train of Northumberland on the journey, he could not have been present at the conference.

Note 2. Accounts and Extracts, II. p. 219.

Note 1. MS. Ambassades, pp. 134, 135. Mr. Allen's Extracts.

Note q. The style of the duke his father was, John, the son of the King of England, Duke of Guienne and Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Lincoln, and Leicester, Steward of England.2 " The word seneshal," says Rastall, "was borrowed by the French of the Germans; and signifies one that hath the dispensing of justice in some particular cases, as the High Steward of England;"1a the jurisdiction of his court, by the statute,2a" shall not pass the space of twelve miles to be counted from the lodgings of our Lord the King."

These "particular cases" would, however, have secured to him a power of exercising his vengeance upon the parties who are immediately afterwards named. But the request urged with such apparent humility was only a part of the varnish of the plot. He had not waited for Richard's consent, having already, within two days after his arrival at Chester, assumed the title upon his own authority. In Madox, Formulare Anglicanum, p. 327, is a letter of safe conduct from Henry to the prior of Beauval, dated from that place, August 10, 23 Richard II. in which he styles himself" Henry, Due de Lancastre,Conte de Derby, de Leycestre, de Herford, et de Northampton, Seneschal d'Angleterre."

He conferred the office upon Thomas, his second son, by patent dated October 8, 1399; constituting at the same time Thomas Percy Deputy High Steward during the minority of the prince.3a

Note 2. Cotton's Abridgement, p. 343.

Note 1a. Termes de la Ley. v. Sene

Note 2a. 13 Ric. II. St. 1. c. 3.

Note 3a. Rymer, Fœdera, VIII. p. 90.

Illustration 11. King Richard II of England (age 32), standing in black and red, meeting with Henry Percy 1st Earl of Northumberland (age 57) at Conwy Castle [Map].

The Deposition of King Richard II. Then replied the earl, "Sire, let the body of our Lord be consecrated. I will swear that there is no deceit in this affair; and that the duke will observe the whole as you have heard me relate it here." Each of them devoutly heard mass:u then the earl without farther hesitation made oath upon the body of our Lord. Alas! his blood must have turned (at it), for he well knew to the contrary; yet would he take the oath,w as you have heard, for the accomplishment of his desire, and the performance of that which he had promised to the duke, who had sent him to the king.

Note u. The translator, in the course of his enquiries, not long since took this metrical history and compared it upon the spot with the castle of Conway. There he recognised the venerable arch of the eastern window of the chapel still entire, where must have stood the altar at which this mass was performed, when the fatal oath was taken. The chapel, in which Richard conferred with his friends, is at the eastern extremity of the hall.

Note w. Unfortunately this is not a solitary instance of such abominable depravity. Sir Emeric of Pavia, Captain of the castle of Calais, in 22 Edw. III swore upon the sacrament to Lord Geoffry Charney that he would deliver up that castle to him for 20,000 crowns of gold: but he communicated the secret to the King of England, and the French were foiled in their attempt. "A thing," says Barnes, "scarce credible among Christians;" though he obscurely adduces another case of the same nature in his own time. Too many more might be found to add to the melancholy list. It must be admitted that the abuse of absolution by the church perniciously weakened the effect of such bonds of conscience, and encouraged the crime; but some periods seem more particularly infected with these blots upon the page of history; and certainly the age in which the metrical history was written had been profligate in the highest degree, with regard to what Lydgate calls, "assured othes at fine untrewe."

Richard and Bolingbroke appear to have been both guilty of this species of perjury. The first is accused with having broken a corporeal oath, in the instance of his uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, and one of another description sworn to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Carte, ever ready to vindicate the king at all hazards, treats these accusations with contempt. "The substance of the charge," he says, "is either false, trifling, or impertinent." But it is easier to deny than to disprove: he has not attempted to make it clear that the allegations are untrue; and unless he could have done it, they can never be looked upon as "trifling or impertinent." They came indeed from Richard's enemies, who stuck at nothing which could blacken his character, or make him appear unworthy of his exalted station; but there is much in his own conduct which might dispose an impartial person to suspect, that these are not aspersions that could easily have been refuted, even at the time in which they were advanced. It may be inferred that he had imbibed no serious impressions of the solemnity of oaths from the levity of an observation made by him at the installation of Scroope, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry, August 9, 1386. After that prelate had sworn to be faithful to the church according to the prescribed form, the king, in the hearing of all present, and apparently, as the Lichfield historian represents it, in the most idle manner observed to him, Certe, domini, magnum præstitisti juramentum [Truly, my lords, you have sworn a great oath.]. Without the slightest wish to overstrain the bearing of these words for the establishment of a point, I cannot but consider that they clearly admit of the interpretation which has been assigned to them.

Henry of Lancaster was also manifestly perjured as to the oaths upon the sacrament which he took at Doncaster and Chester, to assure the public of the unambitious views with which he designed to carry on his proceedings. If charity might incline us at first to believe, with Daniel,

"That then his oath with his intent agreed;"

a closer investigation of his temper and behaviour from his first setting foot on shore to his calling together the parliament, shews that his mind was bent upon a higher aim. The challenge of the Percys sent to him before the battle of Shrewsbury, and Scroope's manifesto tax him with perjury in the most unqualified manner.

The grossest perjury was lightly thought of, and unblushingly committed in England. The citizens of Lincoln were notorious for it; and the biographer of Spencer, Bishop of Norwich, commends him for the steps that he took to expel it from the courts of inquest. and assize in his diocese. Sir Roger Fulthorpe, one of the judges, was guilty of this offence; and all the members, peers, clergy, and commons, of the vindictive parliament of 1397, swore to observe every judgment, ordinance, and declaration made therein; and were afterwards as little mindful of their obligation as if it had never been entered into. "What reliance could be placed on such oaths," says Lingard, "it is difficult to conceive. Of the very men who now swore, the greater part had sworn the contrary ten years before; and as they violated that oath now, so did they violate the present before two years more had elapsed."

Not a little of this general depravity may be attributable, I fear, to the evil example and arbitrary authority of the king; who, when he found his power declining, more than ever adopted this injurious mode of securing the obedience of his subjects. At that time, as it is found at all other times, the frequent requirement of these sacred pledges lessened the respect due to them; and whether they were by the cross of Canterbury, or the shrine of Saint Edward, the Holy Evangelists, or the body of our Lord, they produced little or no impression; or they were deliberately undertaken with mental reservation, and rendered subservient to the purpose of the day.

Illustration 12. Jean Creton Chronicler. Henry Percy 1st Earl of Northumberland (age 57) swearing an oath in the Chapel of Conwy Castle [Map] with King Richard II of England (age 32), in black and red, looking on.

On 1st April 1401 Rhys ap Tudor took at Conwy Castle [Map].

On 1st April 1401 Gwilym ap Tudor Tudor took at Conwy Castle [Map].

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, a canon regular of the Augustinian Guisborough Priory, Yorkshire, formerly known as The Chronicle of Walter of Hemingburgh, describes the period from 1066 to 1346. Before 1274 the Chronicle is based on other works. Thereafter, the Chronicle is original, and a remarkable source for the events of the time. This book provides a translation of the Chronicle from that date. The Latin source for our translation is the 1849 work edited by Hans Claude Hamilton. Hamilton, in his preface, says: "In the present work we behold perhaps one of the finest samples of our early chronicles, both as regards the value of the events recorded, and the correctness with which they are detailed; Nor will the pleasing style of composition be lightly passed over by those capable of seeing reflected from it the tokens of a vigorous and cultivated mind, and a favourable specimen of the learning and taste of the age in which it was framed." Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Around December 1644 John Owen (age 44) was appointed Governor of Conwy Castle.

Around 1775. Paul Sandby (age 44). "Conwy Castle [Map]".

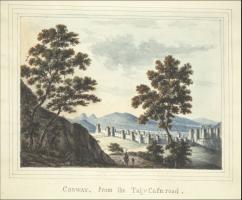

1795. John Ingleby (age 46). "Conwy Castle [Map] from the Talycafn road".

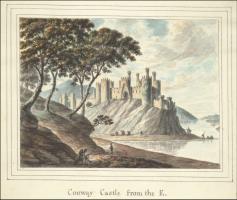

1795. John Ingleby (age 46). "Conwy Castle [Map] from the E[ast]".

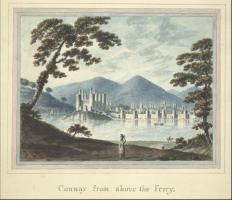

1795. John Ingleby (age 46). "Conwy Castle [Map] from above the Ferry".

Before 1809. Paul Sandby (age 77). "Conwy Castle [Map]".

Before 1852. Samuel Prout (age 68). The Great Hall of Conwy Castle [Map].

The River Conwy rises on the on the Migneint moor where a number of small streams flow into Llyn Conwy [Map] from where it flows more or less north through Betws-y-Coed [Map], under Llanrwst Bridge, Clywd [Map] past Conwy Castle [Map] where it joins the Irish Sea.