Europe, British Isles, South-East England, Surrey, Nonsuch Park Cheam, Nonsuch Palace [Map]

Nonsuch Palace is in Nonsuch Park Cheam, Surrey.

Stane Street to Chichester is a 91km Roman Road from Noviomagus Reginorum [Map] aka Chichester to London crossing the land of the Atrebates in use by 70AD. Its route took it from London Bridge [Map] along Newington Causeway [Map] past Merton Priory, Surrey [Map] to Ewell [Map], through Sutton, Surrey [Map], past the boundary of Nonsuch Palace [Map] to Thirty Acre Barn, Surrey [Map], then near to Juniper Hall Field Centre, Surrey [Map] near Mickleham, then crossing the River Mole near to Burford Bridge [Map] southwards to Dorking, Surrey [Map] (although the route here is vague) to North Holmwood, Surrey [Map], Ockley, Surrey [Map], Rowhook, Surrey [Map] after which it crossed the River Arun at Alfodean Bridge, Surrey [Map] where some of the timber piles on which the bridge was built are still present in the river bed. Thereafter the road travels broadly straight to Billingshurst [Map], Pulborough [Map] where it crosses the River Arun again, then passing the Roman Villa at Bignor [Map] before entering the East Gate [Map] at Noviomagus Reginorum aka Chichester.

In 1543 Thomas Cawarden of Bletchingly and Nonsuch was appointed Keeper of Nonsuch Palace [Map] which post he held until Nov 1556.

Diary of Edward VI. 08 Sep 1550. Removing to Nonesuch [Map].

Henry Machyn's Diary. 05 Aug 1559. The v day of August the Quen('s) (age 25) grace removyd from Eltham [Map] unto Non-shyche [Map], my lord of Arundell('s) (age 47), and ther her grace had as gret cher evere nyght, and bankettes [banquets]; but the sonday at nyght my lord of Arundell('s) howse mad her a grett bankett [banquet] at ys cost, the wyche kyng Henry the viij byldyd, as ever was sene, for soper, bankett, and maske, with drumes and flutes, and all the mysyke that cold be, tyll mydnyght; and as for chere has nott bene sene nor hard. [On monday] the Quen('s) grace stod at her standyng [in the further park,] and ther was corse [coursing] after; and at nyght the Quen .... and a play of the chylderyn of Powlles and ther master Se[bastian], master Phelypes, and master Haywod, and after a grett bankett as [ever was s[ene, with drumes and flutes, and the goodly banketts [of dishes] costely as ever was sene and gyldyd, tyll iij in mornyng; and ther was skallyng of yonge lordes and knyghtes of the ....

Note. P. 206. Master Sebastian, Phdips, and Haywood. "Sebastian scolemaister of Powles" gave queen Mary on new-year's day 1557 "a book of ditties, written." (Nichols's Progresses, &c. of Q. Elizabeth, 1823, vol. i. p. xxxv.) Mr. Collier supposes his surname to have been Westcott (Annals of the Stage, i. 155).—Robert Phelipps was one of the thirtytwo gentlemen of the chapel to king Edward VI. (Hawkins's History of Music, vol. iii. p. 481.—Of John Heywood as an author of interludes and master of a company of "children" players various notices will be found in Mr. Collier's wor

Note. P. 206. The Queen's grace stood at her standing in the further park. "Shooting at deer with a cross-bow (remarks Mr. Hunter in his New Illustrations of Shakespeare) was a favourite amusement of ladies of rank; and buildings with flat roofs, called stands or standings, were erected in many parks, as in that of Sheffield, and in that of Pilkington near Manchester, expressly for the purpose of this diversion." They seem to have been usually concealed by bushes or trees, so that the deer would not perceive their enemy. In Shakspere's Love-Labours Lost, at the commencement of the fourth Act, the Princess repairs to a Stand—

Then, Forester my friend, where is the bush

That we must stand and play the murtherer in?

Forester. Here-by, upon the edge of yonder coppice,

A Stand where you may make the fairest shoot.

Mr. Hunter further remarks that they were often made ornamental, as may be concluded from the following passage in Goldingham's poem called "The Garden Plot," where, speaking of a bower, he compares it with one of these stands—

To term it Heaven I think were little sin,

Or Paradise, for so it did appear;

So far it passed the bowers that men do banquet in,

Or standing made to shoot at stately deer.

Henry Machyn's Diary. 10 Aug 1559. The x day of August, the wyche was sant Laurans day, the Quen('s) (age 25) grace removyd from Non-shyche [Map] unto Hamtun cowrte [Map].

Note. P. 206. Nonsuch. A memoir by the present writer on the royal palace of Nonesuch will be found in the Gentleman's Magazine for August 1837, New Series, vol. VIII. pp. 135–144. The earl of Arundel, as lord steward of the household, had obtained an interest in it, which seems almost to have amounted to an alienation, but it reverted to the Crown in 1591. His first dealings with it were resisted by sir Thomas Cawarden, (the subject of the following Note,) who had been the previous keeper.

Henry Machyn's Diary. 25 Aug 1559. The xx .. day of August ded at Non-shyche [Map] ser Thomas Carden knyght, devyser of all bankettes [banquets] and bankett-howses [banquet-houses], and the master of reyvelles and serjant of the tenttes.

Note. P. 208. Death and funeral of sir Thomas Cawarden. Knighted by Henry VIII. at the siege of Boulogne in 1544, a gentleman of the king's privy chamber in 1546, and in his latter years master of the revels, tents, and pavilions. His altar-tomb remains in Bletchingley church, but without inscription. (Manning and Bray's Surrey, ii. 300.) Among other documents relating to sir Thomas Cawarden and his office, published in the Loseley Manuscripts, edited by A. J. Kempe, esq. F.S.A. 1835, Svo. are (p. 175) his will dated St. Bartholomew's day 1559, and (p. 179) the charges of his obsequies, amounting to 96l. 15s. 1½d. and the funeral feast to 32l. 16s. 8d. The death of his wife shortly followed, and the charges of her funeral are also stated.

On 25 Aug 1559 Thomas Cawarden of Bletchingly and Nonsuch died at East Horsley, Surrey [Map] or Nonsuch Palace [Map].

On 02 Aug 1591 Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland (age 57) left at Nonsuch Palace [Map] to commence her Royal Progress. She travelled south to Mansion House Leatherhead, Surrey [Map]; the home of Edmund Tilney (age 55).

In Sep 1599 when the Queen (age 65) moved her Court to Nonsuch Palace [Map]. Margaret Radclyffe of Ordsall Hall (age 26) returned to her childhood home of Ordsall Hall, Lancashire [Map] where her condition continued to deteriorate.

On 28 Sep 1599 Robert Devereux 2nd Earl Essex (age 33) presented himself to Elizabeth (age 66) in her bedchamber at Nonsuch Palace [Map] where he found the queen newly up, the hair about her face. Elizabeth had just a simple robe over her nightdress, her wrinkled skin was free of cosmetics and, without her wig. Essex saw her bald head with just wisps of thinning grey hair 'hanging about her ears'. The Queen confined the Earl to his rooms with the comment that "an unruly beast must be stopped of his provender.".

Before 24 Jul 1601. Joris Hoefnagel (age 59). Drawing of Nonsuch Palace [Map]

Before 24 Jul 1601. Joris Hoefnagel (age 59). Drawing of Nonsuch Palace [Map]

Diary of Anne Clifford 1603. Aug 1603. From Lancilwell we went to Mr Duton’s, where we continued about a week, and had great entertainment, and at this time kept a fast by reason of the plague, which was generally observed all over England. From Mr Duton’s we went to Barton, one Mr Dormer’s, where Mrs Humphrie her mother and she entertained us with great kindness ; from thence we went often to the Court at Woodstock, where my Aunt of Bath followed her suit to the King, and my Mother wrote letters to the King, and her means were by my Lord of [blank in MS] and to the Queen (age 28) by my Lady of Bedford. My Father at this time followed his suit to the King about the Buder [Border ?] lands, so that sometimes my Mother and he did meet, when their countenance did show the dislike they had one of the other, yet he would speak to me in a slight fashion and give me his blessing. While we lay there we rid through Oxford once or twice, but whither we went I remember not. There we saw the Spanish Ambassador, who was then new come to England about the peace.1 While we lay at Barlow [Barton ?], I kept so ill a diet with Mts Mary Carey and M's S. Cuison on eating fruit so that I shortly fell into the same sickness. From this place my Aunt of Bath, having little hope of her suit, took her leave of my Mother and returned into the west country. While they lay at Barton, my Mother and my aunt paid for the charge of the house equally.

Note 1. Not long before Michaelmas, myself, my Coz. Frances Bouchier, Mrs Goodwin and Mrs Howbridge waiting on us, [went?] in my mother’s coach from Barton to Cookham where my Uncle Russell2 his wife and son then lay. The next day we went to Nonsuch [Map] where Prince Henry and her Grace lay, where stayed about a week, and left my cousin there, who was proposed to continue with her Grace, but I came back by Cookham, and came to Barton before my Aunt of Bath went into the country.

Note 2. Lord and Lady Russell of Thornhaugh and their son Francis, afterwards 4th Earl of Bedford.

Pepy's Diary. 26 Jul 1663. We rode out of the town through Yowell beyond Nonesuch House [Map] a mile, and there our little dogg, as he used to do, fell a-running after a flock of sheep feeding on the common, till he was out of sight, and then endeavoured to come back again, and went to the last gate that he parted with us at, and there the poor thing mistakes our scent, instead of coming forward he hunts us backward, and runs as hard as he could drive back towards Nonesuch [Map], Creed and I after him, and being by many told of his going that way and the haste he made, we rode still and passed him through Yowell, and there we lost any further information of him. However, we went as far as Epsum almost, hearing nothing of him, we went back to Yowell, and there was told that he did pass through the town. We rode back to Nonesuch [Map] to see whether he might be gone back again, but hearing nothing we with great trouble and discontent for the loss of our dogg came back once more to Yowell, and there set up our horses and selves for all night, employing people to look for the dogg in the town, but can hear nothing of him. However, we gave order for supper, and while that was dressing walked out through Nonesuch Park [Map] to the house, and there viewed as much as we could of the outside, and looked through the great gates, and found a noble court; and altogether believe it to have been a very noble house, and a delicate park about it, where just now there was a doe killed, for the King (age 33) to carry up to Court. So walked back again, and by and by our supper being ready, a good leg of mutton boiled, we supped and to bed, upon two beds in the same room, wherein we slept most excellently all night.

Pepy's Diary. 11 Aug 1665. I to the Exchequer, about striking new tallys, and I find the Exchequer, by proclamation, removing to Nonesuch [Map]1. Back again and at my papers, and putting up my books into chests, and settling my house and all things in the best and speediest order I can, lest it should please God to take me away, or force me to leave my house. Late up at it, and weary and full of wind, finding perfectly that so long as I keepe myself in company at meals and do there eat lustily (which I cannot do alone, having no love to eating, but my mind runs upon my business), I am as well as can be, but when I come to be alone, I do not eat in time, nor enough, nor with any good heart, and I immediately begin to be full of wind, which brings my pain, till I come to fill my belly a-days again, then am presently well.

Note 1. Nonsuch Palace, near Epsom, where the Exchequer money was kept during the time of the plague.

Pepy's Diary. 20 Sep 1665. After dinner I to the office there to write letters, to fit myself for a journey to-morrow to Nonsuch [Map] to the Exchequer by appointment.

Pepy's Diary. 28 Sep 1665. Up, and being mightily pleased with my night's lodging, drank a cup of beer, and went out to my office, and there did some business, and so took boat and down to Woolwich, Kent [Map] (having first made a visit to Madam Williams, who is going down to my Lord Bruncker (age 45)) and there dined, and then fitted my papers and money and every thing else for a journey to Nonsuch [Map] to-morrow.

Pepy's Diary. 29 Sep 1665. To sleep till 5 o'clock, when it is now very dark, and then rose, being called up by order by Mr. Marlow, and so up and dressed myself, and by and by comes Mr. Lashmore on horseback, and I had my horse I borrowed of Mr. Gillthropp, Sir W. Batten's (age 64) clerke, brought to me, and so we set out and rode hard and was at Nonsuch [Map] by about eight o'clock, a very fine journey and a fine day. There I come just about chappell time and so I went to chappell with them and thence to the several offices about my tallys, which I find done, but strung for sums not to my purpose, and so was forced to get them to promise me to have them cut into other sums. But, Lord! what ado I had to persuade the dull fellows to it, especially Mr. Warder, Master of the Pells, and yet without any manner of reason for their scruple.

Pepy's Diary. 20 Nov 1665. Up before day, and wrote some letters to go to my Lord, among others that about W. Howe, which I believe will turn him out, and so took horse for Nonsuch [Map], with two men with me, and the ways very bad, and the weather worse, for wind and rayne. But we got in good time thither, and I did get my tallys got ready, and thence, with as many as could go, to Yowell [Map], and there dined very well, and I saw my Besse, a very well-favoured country lass there, and after being very merry and having spent a piece I took horse, and by another way met with a very good road, but it rained hard and blew, but got home very well. Here I find Mr. Deering come to trouble me about business, which I soon dispatched and parted, he telling me that Luellin hath been dead this fortnight, of the plague, in St. Martin's Lane, which much surprised me.

Pepy's Diary. 27 Nov 1665. After dinner a great deal alone with Sir G. Carteret (age 55), who tells me that my Lord hath received still worse and worse usage from some base people about the Court. But the King (age 35) is very kind, and the Duke do not appear the contrary; and my Chancellor (age 56) swore to him "by--I will not forsake my Lord of Sandwich (age 40)". Our next discourse is upon this Act for money, about which Sir G. Carteret (age 55) comes to see what money can be got upon it. But none can be got, which pleases him the thoughts of, for, if the Exchequer should succeede in this, his office would faile. But I am apt to think at this time of hurry and plague and want of trade, no money will be got upon a new way which few understand. We walked, Cocke (age 48) and I, through the Parke with him, and so we being to meet the Vice-Chamberlayne to-morrow at Nonsuch [Map], to treat with Sir Robert Long (age 65) about the same business, I into London, it being dark night, by a hackney coach; the first I have durst to go in many a day, and with great pain now for fear. But it being unsafe to go by water in the dark and frosty cold, and unable being weary with my morning walke to go on foot, this was my only way. Few people yet in the streets, nor shops open, here and there twenty in a place almost; though not above five or sixe o'clock at night.

Pepy's Diary. 28 Nov 1665. Up before day, and Cocke (age 48) and I took a hackney coach appointed with four horses to take us up, and so carried us over London Bridge [Map]. But there, thinking of some business, I did 'light at the foot of the bridge, and by helpe of a candle at a stall, where some payers were at work, I wrote a letter to Mr. Hater, and never knew so great an instance of the usefulness of carrying pen and ink and wax about one: so we, the way being very bad, to Nonsuch [Map], and thence to Sir Robert Longs (age 65) house; a fine place, and dinner time ere we got thither; but we had breakfasted a little at Mr. Gawden's, he being out of towne though, and there borrowed Dr. Taylor's (age 52) sermons, and is a most excellent booke and worth my buying, where had a very good dinner, and curiously dressed, and here a couple of ladies, kinswomen of his, not handsome though, but rich, that knew me by report of The. Turner (age 13), and mighty merry we were.

Evelyn's Diary. 03 Jan 1666. Mr. Packer's (age 47), and took an exact view of the plaster statues and bass-relievos inserted between the timbers and puncheons of the outside walls of the Court; which must needs have been the work of some celebrated Italian. I much admired how they had lasted so well and entire since the time of Henry VIII., exposed as they are to the air; and pity it is they are not taken out and preserved in some dry place; a gallery would become them. There are some mezzo-relievos as big as the life; the story is of the Heathen Gods, emblems, compartments, etc. The palace [Map] consists of two courts, of which the first is of stone, castle like, by the Lord Lumleys (of whom it was purchased), the other of timber, a Gothic fabric, but these walls incomparably beautiful. I observed that the appearing timber-puncheons, entrelices, etc., were all so covered with scales of slate, that it seemed carved in the wood and painted, the slate fastened on the timber in pretty figures, that has, like a coat of armor, preserved it from rotting. There stand in the garden two handsome stone pyramids, and the avenue planted with rows of fair elms, but the rest of these goodly trees, both of this and of Worcester Park adjoining, were felled by those destructive and avaricious rebels in the late war, which defaced one of the stateliest seats his Majesty had.

Evelyn's Diary. 03 Jan 1666. I supped in Nonesuch House [Map], whither the office of the Exchequer was transferred during the plague, at my good friend.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Sep 1666. Up about five o'clock, and where met Mr. Gawden at the gate of the office (I intending to go out, as I used, every now and then to-day, to see how the fire is) to call our men to Bishop's-gate [Map], where no fire had yet been near, and there is now one broke out which did give great grounds to people, and to me too, to think that there is some kind of plot1 in this (on which many by this time have been taken, and, it hath been dangerous for any stranger to walk in the streets), but I went with the men, and we did put it out in a little time; so that that was well again. It was pretty to see how hard the women did work in the cannells, sweeping of water; but then they would scold for drink, and be as drunk as devils. I saw good butts of sugar broke open in the street, and people go and take handsfull out, and put into beer, and drink it. And now all being pretty well, I took boat, and over to Southwarke [Map], and took boat on the other side the bridge, and so to Westminster, thinking to shift myself, being all in dirt from top to bottom; but could not there find any place to buy a shirt or pair of gloves, Westminster Hall [Map] being full of people's goods, those in Westminster having removed all their goods, and the Exchequer money put into vessels to carry to Nonsuch [Map]; but to the Swan [Map], and there was trimmed; and then to White Hall, but saw nobody; and so home. A sad sight to see how the River looks: no houses nor church near it, to the Temple [Map], where it stopped.

Note 1. The terrible disaster which overtook London was borne by the inhabitants of the city with great fortitude, but foreigners and Roman Catholics had a bad dime. As no cause for the outbreak of the fire could be traced, a general cry was raised that it owed its origin to a plot. In a letter from Thomas Waade to Williamson (dated "Whitby, Sept. 14th") we read, "The destruction of London by fire is reported to be a hellish contrivance of the French, Hollanders, and fanatic party" (Calendar of State Papers, 1666-67, p. 124).

Pepy's Diary. 27 Sep 1666. A very furious blowing night all the night; and my mind still mightily perplexed with dreams, and burning the rest of the town, and waking in much pain for the fleete. Up, and with my wife by coach as far as the Temple [Map], and there she to the mercer's again, and I to look out Penny, my tailor, to speak for a cloak and cassock for my brother, who is coming to town; and I will have him in a canonical dress, that he may be the fitter to go abroad with me. I then to the Exchequer, and there, among other things, spoke to Mr. Falconbridge about his girle I heard sing at Nonsuch [Map], and took him and some other 'Chequer men to the Sun Taverne, and there spent 2s. 6d. upon them, and he sent for the girle, and she hath a pretty way of singing, but hath almost forgot for want of practice. She is poor in clothes, and not bred to any carriage, but will be soon taught all, and if Mercer do not come again, I think we may have her upon better terms, and breed her to what we please.

Pepy's Diary. 23 Aug 1667. Then abroad to White Hall in a Hackney-coach with Sir W. Pen (age 46): and in our way, in the narrow street near Paul's, going the backway by Tower Street [Map], and the coach being forced to put back, he was turning himself into a cellar1, which made people cry out to us, and so we were forced to leap out-he out of one, and I out of the other boote2 Query, whether a glass-coach would have permitted us to have made the escape?3 neither of us getting any hurt; nor could the coach have got much hurt had we been in it; but, however, there was cause enough for us to do what we could to save ourselves.

Note 1. So much of London was yet in ruins.-B.

Note 2. The "boot" was originally a projection on each side of the coach, where the passengers sat with their backs to the carriage. Such a "boot" is seen in the carriage [on the very right] containing the attendants of Queen Elizabeth, in Hoefnagel's well-known picture of Nonsuch Palace [Map], dated 1582. Taylor, the Water Poet, the inveterate opponent of the introduction of coaches, thus satirizes the one in which he was forced to take his place as a passenger: "It wears two boots and no spurs, sometimes having two pairs of legs in one boot; and oftentimes against nature most preposterously it makes fair ladies wear the boot. Moreover, it makes people imitate sea-crabs, in being drawn sideways, as they are when they sit in the boot of the coach". In course of time these projections were abolished, and the coach then consisted of three parts, viz., the body, the boot (on the top of which the coachman sat), and the baskets at the back.

Note 3. See note on introduction of glass coaches, September 23rd, 1667.

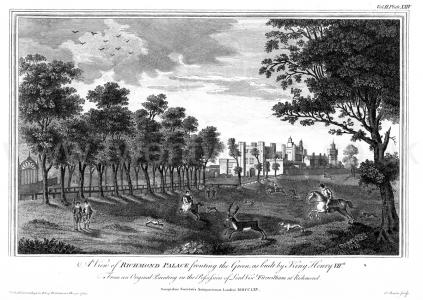

Vesta Monumenta. 1765. Plate 2.24. Nonsuch Palace [Map]. Engraved by James Basire Sr. (age 35).