Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Lincolnshire, Blankney

Blankney, Lincolnshire is in Lincolnshire.

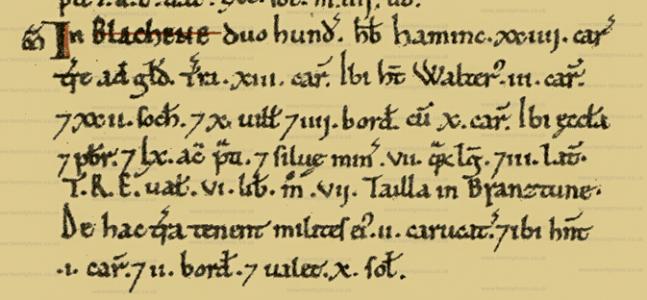

1086. In the Doomsday Book Blankney, Lincolnshire is described as in the hundred of Langoe and the county of Lincolnshire.

It had a recorded population of 39 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

Land of Walter of Aincourt: Households: 10 villagers. 22 freemen. 6 smallholders. 1 priest. Land and resources: Ploughland: 13 ploughlands. 4 lord's plough teams. 10 men's plough teams. Other resources: Meadow 60 acres. Woodland 7 * 3 furlongs. 1 church. Valuation: Annual value to lord: 7 pounds 10 shillings in 1086; 6 pounds in 1066.

Owners: Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Walter of Aincourt. Lords in 1086: Walter of Aincourt; men-at-arms. Lord in 1066: Hemming

Around 1250 Edmund Deincourt 1st Baron Deincourt was born to John Deincourt 7th Lord Deincourt (age 25) and Agnes Neville (age 29) at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

Around 1266 John Deincourt was born to Edmund Deincourt 1st Baron Deincourt (age 16) and Isabel Mohun Baroness Deincourt (age 23) at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

Around 1327 William Deincourt was born to William Deincourt 1st Baron Deincourt (age 26) and Millicent Zouche Baroness Deincourt at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

Around 1344 Margaret Deincourt Baroness Tibetot was born to William Deincourt 1st Baron Deincourt (age 43) and Millicent Zouche Baroness Deincourt at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

On 22 Jun 1379 Millicent Zouche Baroness Deincourt died at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

On 24 Feb 1404 Alice Deincourt 6th Baroness Deincourt, Baroness Lovel and Sudeley was born to John Deincourt 4th Baron Deincourt (age 21) and Joan Grey at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

On 11 May 1406 John Deincourt 4th Baron Deincourt (age 24) died at Blankney, Lincolnshire. He was buried at Blankney, Lincolnshire. His son William Deincourt 5th Baron Deincourt (age 3) succeeded 5th Baron Deincourt.

On 20 Jun 1433 Alice Neville Baroness Deincourt (age 75) died at Blankney, Lincolnshire.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth I. John Chaplin's younger brother Robert represented Great Grimsby in Parliament, and was granted a baronetcy, but, dying without a son, the title passed by special remainder to John's grandson (age 19) and namesake, a son of Porter Chaplin. This young man died of the small-pox in 1730, after a few days' illness; as he left no male heir and only a posthumous daughter, the title became extinct and the property of Tathwell, which was entailed, went to his uncle Thomas (age 46), another son of John Chaplin. It is to Thomas Chaplin that his descendants owed the estate of Blankney, which he bought and made his home in 1719. From that date until the close of the nineteenth century, Blankney was the Chaplin home.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth I. It must have been immediately after the marriage of Diana Chaplin (age 18), and probably in honour of that event, that a masquerade was held at Blankney Hall, of which a list of some of the principal guests and their impersonations has been preserved. Thomas Chaplin having died in 1747, his son John (age 28), who was not yet married, was presumably the host on this occasion. He chose for himself the character of Henry V Ill., and if he enjoyed the same splendid proportions as his descendant, the last Squire, his choice was justified. An old yellow torn sheet of paper has been preserved on which in faded ink is written:

A LIST OF THE COMPANY AS THEY DANCED AT THE MASQUERADE AT BLANKNEY, THE 9TH JANUARY 1749.

Lord George Manners (age 25)... A Spaniard

Mr. Glover... A Rich Vandyke

Mr. Chaplin (age 28)... King Harry the 8th

Mr. C. Chaplin (age 18)... A Huzsar

Mr. Amcotts... A Venetian Dancer

Mr. Nevill... Mercury

Sir Francis Dashwood (age 40)... Pluto (King of Hell with a Little infernal boy bearing up his train)

Mr. Pownall... A Vandyke

Mr. Thornton... A Dancer

Capt. Bell... A Chimney Sweeper (in black Satin)

Duke of Kingston (age 38)... In a Gold White Domino

Mr. Carter... A Priest

Major Gibbon... Queen Elizabeth's Porter

Mr. Dashwood (age 32), Bror to Sir Francis... A Russian

Mr. Stevens... A Black Domino

Mr. Porter... Mercury

Mr. Foster... A Domino

Mr. Willis... A Sailor

Mr. King... A Vandyke

Mr. Richd Welby... A Hungarian

Lady Vere Bertie.. A fair Maid of the Inn

Lady Tyrconnel... A Spanish Lady

Miss Wheat... Rubens' Wife

Miss Thornton... Flora

Miss Disney... Violette

Miss N. Amcotts... The Rising Morn

Miss Carter... Queen of the Scots as a widow

Lady Thorold... A Spanish Lady

Miss Mainwaring... Representing Night in a Black Gown with Stars

Miss Maddison... A Country Girl

Lady Dashwood... A Vandyke

Miss Bertie... A Dancer

Miss Bet Hales... An old-fashioned Lady

Mrs. Willie... A Country Girl

Miss I. Cust... Italian Dancer

Miss King... Aurette

Miss N. Welby... A Quaker

Mrs. Porter... A Turkish Lady

Miss Hales... A Country Girl

Miss Lucy Cust... An old Lady

COMPANY THAT SAT BY

Lady Vere Bertie... An Italian Peasant

Lord Tyrconnel... In a blue & silver Domino

Colonel Armiger...

Young Mr. Wills... Capt. Flask

Mr. Middlemore... In a Pink Domino

Mr. Villarial... Scaramouch

Mrs. Chaplin... An Old Woman

Lady George Manners (the Bride) [Diana Chaplin (age 18)]... A Jardiniere

Mrs. Wills... Queen Elizabeth

Miss Truman... Columbine

Among all this motley crowd, not the least imposing figure was probably that of Sir Francis Dashwood (age 40), appropriate in the character chosen, since he was one of the most prominent supporters of the Hell Fire Club.1

Note 1. He was Chancellor of the Exchequer. Wilkes described him as one who from puzzling all his life at tavern bills was called by Lord Bute to administer the finances of the Kingdom which were 100 millions in debt He was the founder of the Society of the Franciscans at Medmenham Abbey, where the door was surmounted by the motto, "Fay ce que voudras" ["Do Whatever You Want"], and where he played the part of an immoral buffoon for the amusement of Privy Councillors and Members of Parliament.

In 1892 Henry Chaplin 1st Viscount Chaplin (age 51) sold the heavily mortgaged Blankney, Lincolnshire to the principal mortgagee William Henry Forester Denison 1st Earl Londesborough (age 57).

On 17 Apr 1937 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough (age 42) died. He was buried at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. The Earl had become ill and it was decided to to move him to London for treatment; he died on the journey. Earl Londesborough in Yorkshire extinct. The impact of death duties necessitated the sale of Blankney, Lincolnshire to Mr William Parker of Norfolk. The Countess, Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough (age 33), and her daughter Zinnia Rosemary Denison, continued to live on the estate.

Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough:

On 13 Nov 1894 he was born to William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

On 12 Sep 1920 George Denison 3rd Earl of Londesborough died unmarried. His brother Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough succeeded 4th Earl Londesborough in Yorkshire. On 07 Sep 1935 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough were married at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. He the son of William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. That was the last time I saw Blankney — except once more, in a dream, a singular incident which I will relate. And since it concerned my cousin Hugo, whose marriage I had attended that summer afternoon some two years before, I must first explain that though we had always been friendly when we met, of recent years I had not seen much of him, for I was often abroad, while all his interests, hunting and racing, were of a different kind from mine and tended to keep him in the country .... It occurred in the early spring of 1937, when I was living in a villa near Vevey, on the Lake of Geneva. One night I was very restless, waking up at about two, and finding myself unable to get to sleep again for hours Eventually, about 6.30 in the morning, I fell into a long, troubling and involved dream, which yet did not the realm of nightmare. In it, I was in the Saloon at Blankney again, and Hugo, the owner of it, was talking to me very urgently. His words were simple enough, but laden with a weight of presage, and of sad and menacing feeling, and I knew that in his last sentence he was conveying to me something importance. He said, "There will be a party here at Blankney in ten days' time. All the relations are coming. They arrive by special train in the morning, and leave by special train in the afternoon." .... Then I woke up ; to find I was being called by my servant. He handed me The Times of the previous day — it always arrived in Vevey twenty-four hours after it had come out in London. I sat up, still unreasonably distressed, opened the paper — and the first heading that caught my eye as I did so was Serious Illness of Lord Londesborough .... It was impossible to misapprehend so clear a portent, although in my dream seen in reverse: but I still hoped that I might be wrong, because I knew that all the members of Hugo's family had hitherto been buried at Londesborough, and this detail, so incorrect, seemed to falsify my reading of it. Howbeit, I was still so much oppressed by the feeling of the dream, that I told two friends, who were staying with me at the time, of it and of the sequel in the paper .... For a while it appeared that Hugo was better, but a week later he died, and three days after that was buried at Blankney.

On 07 Sep 1935 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough were married at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. He the son of William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. That was the last time I saw Blankney — except once more, in a dream, a singular incident which I will relate. And since it concerned my cousin Hugo, whose marriage I had attended that summer afternoon some two years before, I must first explain that though we had always been friendly when we met, of recent years I had not seen much of him, for I was often abroad, while all his interests, hunting and racing, were of a different kind from mine and tended to keep him in the country .... It occurred in the early spring of 1937, when I was living in a villa near Vevey, on the Lake of Geneva. One night I was very restless, waking up at about two, and finding myself unable to get to sleep again for hours Eventually, about 6.30 in the morning, I fell into a long, troubling and involved dream, which yet did not the realm of nightmare. In it, I was in the Saloon at Blankney again, and Hugo, the owner of it, was talking to me very urgently. His words were simple enough, but laden with a weight of presage, and of sad and menacing feeling, and I knew that in his last sentence he was conveying to me something importance. He said, "There will be a party here at Blankney in ten days' time. All the relations are coming. They arrive by special train in the morning, and leave by special train in the afternoon." .... Then I woke up ; to find I was being called by my servant. He handed me The Times of the previous day — it always arrived in Vevey twenty-four hours after it had come out in London. I sat up, still unreasonably distressed, opened the paper — and the first heading that caught my eye as I did so was Serious Illness of Lord Londesborough .... It was impossible to misapprehend so clear a portent, although in my dream seen in reverse: but I still hoped that I might be wrong, because I knew that all the members of Hugo's family had hitherto been buried at Londesborough, and this detail, so incorrect, seemed to falsify my reading of it. Howbeit, I was still so much oppressed by the feeling of the dream, that I told two friends, who were staying with me at the time, of it and of the sequel in the paper .... For a while it appeared that Hugo was better, but a week later he died, and three days after that was buried at Blankney.

Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough: On 15 May 1903 she was born to Edgar Lubbock.

Zinnia Rosemary Denison: On 25 Nov 1937 she was born to Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough. She was born posthumously her father having died six months before her birth. On 13 Jul 1997 Zinnia Rosemary Denison died.

Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Lincolnshire, Blankney Hall

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: 2 Family and Social Life Part I. On his twenty-first birthday in December 1862, Harry Chaplin came into his heritage. In his old age he was fond of saying that on his uncle's death he had inherited properties in three different counties—which was in fact the case. In addition to the large estates of Blankney, Tathwell, and Metheringham, Temple Brewer and Little Caythorpe, and the smaller ones of Hallington, Hougham, Maltby, Raithby, and Scopwick, all in Lincolnshire, and covering about 25,000 acres, two small properties also came to him in Nottinghamshire and in Yorkshire, both of which were, however, sold shortly after his majority.

On 29 Apr 1890 Hermit (age 26) died at Blankney Hall. His skeleton was given to the Royal College of Vetinary Surgeons. A hoof was presented to the Prince of Wales who had it fashioned into an ink-stand, writing:

Marlborough House,

July 27/90.

My Dear Harry (age 49) — How kind of you to have sent me the hoof of dear old ! so prettily mounted, which I shall always greatly value and constantly use as an inkstand.

I am also very much touched by the kind expressions in your letter wishing me good luck with my racehorses. Though I can never expect to have the good fortune which attended the Dukes of Portland and Westminster, still I hope with patience to win one or more of the classic races with a horse bred by myself. I sincerely hope you may yet be able to come to Goodwood for a part of the time, at any rate.

Thanking you again for your kind remembrance of me and giving me so interesting a souvenir of your "best friend"

From yours very sincerely,

Albert Edward (age 48).

P.S.—I shall always take the shoe about with me.

1900. Photos of Blankney Hall.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. The Scarlet Tree. Chapter 2. Retreats upon an Ideal. Though in the next chapter I shall have to revert for a few pages to my early school-days, in order to sum up their effect, in mind and body, upon at least one boy, here we will leave the scene of them for a while. First, however, I must produce a letter, written in my third term, because it gives, despite cacography, indications of character, in others no less than in myself, and serves as a kind of preface for the chapter that follows .... Victor, to whom it makes reference, was; I must explain, my cousin, exact contemporary and, at that time, chief foe.

04 Nov 1903

Darling Mother,

I hope you are quite well. Do let me know your adres in Naples. The aples have arrived. Thank you so much.

I am better but wish I had no teeth. They are aching as hard as they can go.

Any chance of our going to Londesborough or Blankney for Christmas, do find out first if Victor will be there, because I should not enjoy it if he was. I am also afraid I shall be shy there, and that they will make a fuss if I do not taulk all day like when I was at Blankney last Christmas. Please write to me at once when you get my letter. I do miss you. - Your loving son

Osbert.

P.S. Please let me know about Blankney.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. Nearer, in the park, and in what must have been the meadows beyond — but until a few years ago I never saw Blankney at another season, so could form no idea of the country buried under this enveloping white shroud — were many enormous pits, containing whole armies of Danish invaders. ... Of this my father informed me, for, to tell the truth, he found himself, had he permitted the existence of such a word, bored, in a house where all the interests were of a sporting nature, and, in consequence, called his bluff. Moreover, it was made worse for him by the fact that the remainder of the guests enjoyed themselves to the same extent as he was miserable. Pure self-indulgence. But he could always find solace, he was thankful to say, in thinking over historical associations — so long as they were of the correct period. And here he was fortunate, for the great slaughter, of which these pits were — if only you could see them — the abiding sign, had taken place between a.d. 700 and 800, and nothing much had occurred in this district since then to spoil the idea of it. Therefore, he could always take refuge with the Danish dead, always cause his blood to tingle, by telling me how these huge excavationSj filled with bodies of warriors, killed by the retreating Saxons some eleven hundred years before, had been dug out, and how^ they had been covered first with the branches of trees, on which the earth was then shovelled — that accounted for the mounds. The very thought of it, in the American phrase, made him "feel good". With gusto he described the brave invaders, their bronze helmets and primitive axes, until for the first time I visualised that Wagnerian world of firemen armoured in bronze, with flowing moustaches, and long hair, led by bearded, resonant voiced kings, potbellied, who pledged their cave-loves in blood drunk from the skulls of their enemies. It was not, I found, a world which I much liked: but my father, I recollect, used to declare that if only the members of my mother's family were more intelligent, they would spend their whole time in digging up the bones, instead of in hunting, shooting and going to circuses. He would also tell me — this, I think, in order to make himself feel morc at home in a house given to relatives by marriage - that Blankney had been "held" in the twelth century by the Deincourts, a Norman family of whom, through the Reresbys, we were the representatives, entitled to quarter their arms. (The Londesborough escutchcon he considered, he owned, as shameful, a "horrid eighteenth-century coat, all wrong in heraldry".)

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. In general, each Christmas [at Blankney Hall] the representatives of the older generation were the same, invariably numbering in their company my grandmother [Edith Somerset Countess Londesborough (age 69)], her brother-in-law [Arthur Walsh 2nd Baron Ormathwaite (age 80)] and sister [Katherine Somerset Baroness Ormathwaite (age 73)]. Lord and Lady Ormathwaite, and Sir Nigel (age 77) and Lady Emily Kingscote (age 72). Lord Ormathwaite was even then over eighty — he lived to be ninety-three. Both he and his wife were of a deeply religious nature (it was very noticeable how much more devout were the old than their sons and daughters), and one of the favourite amusements of the children, I remember, was to hide in the broad passage outside the bedroom of this old couple, and listen to the vehement recitation of their lengthy and extremely personal prayers. Another frequent Christmas visitor, until her death in 1903, was Adza Lady Westmorland, who belonged to the same epoch, being the mother of my aunt, and a sister to the 8th Duchess of Beaufort and Lady Emily Kingscote (age 72). She was a godchild of Queen Adelaide, as was her nephew the Duke of Beaufort (age 60)1. Adza Lady Westmorland, indeed, came of a family much devoted to Queen Adelaide, since she was the daughter of that Lord Howe — the 1st Earl Howe — whose singular conduct at the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, when King William IV was living there, had roused the malicious interest of Charles Greville. Lord Howe, a handsome young man "with a delightful wife", hovered dotingly round Queen Adelaide whenever she was in the room, remained gazing at her with eyes full of love and admiration, and behaved altogether, the diarist relates, as though "a boy in love with this frightful spotted majesty" .... Adza Lady Westmorland, as I remember her, was a very old lady in a Bath-chair, who wore a black dress and a large, shady black hat. But she still retained her wonderfully exquisite manners and her great charm, for both of which she had been celebrated. In her time, she had been responsible for several small social innovations for women, such as wearing tweeds and smoking cigarettes.

As for the young, they were for the most part the same as those we saw a few years before at Scarborough: my cousins, Raincliffe — Frank — , and Hugo and Irene Denison, Veronica and Christopher Codrington, Enid Fane (age 13) and her brother, Burghersh (age 14) — who was my particular friend and companion at that time, in the same way that Victor was my enemy elect — , Marigold Forbes, and other young relatives. Entertainments were provided for them — and, as we shall see in a moment, by them — with regularity. Presents were I do not know how much the old or the young plentiful .... enjoyed the parties — scarcely as much as the members of the ruling generation, I should say ; to the old, certainly, these Christmas festivities brought a feeling of sadness, of deposition.... Among the children, I am sure that the child who felt least happy, an alien among her nearest grown-up relations, was my sister. Acutely sensitive, and with her imagination perhaps almost unduly developed by the neglect and sadness of her childhood since she was five, she could find no comfort under these tents. She loved music, it was true — indeed, where music is, there, always, is her home but the music of this house meant little to her, and the formal conversation between children and grown-ups, even if they were trying to be kind, frightened and bored her ; while she did not care for the machinery of the life here ; the continual killings seemed to her to be cruel, even insane. She ought to have asked to go out with the guns, even if she herself did not shoot ; she might at least have attended a meet. And, if anything, my father's inclination to nag at her on the one hand, my mother's, to fall into ungovernable, singularly terrifying rages with her, on the other, because of her non-conformity, seemed stronger when there were people, as here, to feed the fires of their discontent, and other children to set a standard by which to measure her attainments. "Dearest, you ought to make her like killing rabbits," one could hear the fun brigade urging on my mother. But while my father was angry with his daughter for failing to comply with another standard — his for not having a du-Maurier profile, a liking for "lawn-tennis" or being able to sing or play the zither after dinner (it did not affect him that his wife's relations would have been very angry if she had attempted to play the zither at them), he was also disappointed on another score. She seemed far less interested than I was — or even Sacheverell who was only six or seven — in his stories about the Black Death (a subject he had been "reading up" in the British Museum), and she seemed to have no natural feeling for John The Victorians, Stuart Mill's Principles of Political Economy .... I think, appreciated Edith more than did the Edwardians. But Irene was the particular focus for grown-up attention and affection, not bccausc she was the only daughter of the house, but because the delicate loveliness of her appearance, with her fine skin and huge, dark-blue eyes, and a certain kind serenity, unusual in a child of her age, made everyone want to spoil her. But it was in vain she remained absolutely unspoilt, gentle, amiable, full of kindly fccling towards the whole world.

Note 1. Henry Adelbert Wellington FitzRoy, 9th Duke of Beaufort (age 60) (b. 1847), was named Adelbert after Queen Adelaide, and Wellington after the Iron Duke, his godfather and his father’s great-uncle. He died in 1920. His late Royal Highness the Duke Connaught (1850—1942) was one of the two last surviving godsons of the Duke of Wellington, the other and ultimate being the 4th Marquess of Ormonde (age 58) ( 1849-1943).

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth I. A tradition of hidden treasure at Blankney Hall survived for more than a century. When Lord Widdrington was attainted it was said that, foreseeing the confiscation of his land, he endeavoured to secure as much of the movable property as possible by concealing it in secret places, and a legend ran that he had deposited a large chest of plate in a vault beneath the great staircase. The family hopes, however, were dispelled when on one occasion, having workmen in the house, Mr. Charles Chaplin, uncle of the last squire, ordered the vault to be opened. The oak chest was there indeed, but it only contained a salt cellar of white metal and an iron ladle. Either Lord Widdrington had deliberately misled the Government treasure-seekers, or thieves had cheated posterity.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth I. While the adjoining church of St. Oswald's (from which the late Henry Chaplin took his title) was practically rebuilt in the nineteenth century, Blankney Hall was fortunate in escaping the destruction that befell so many castles and houses confiscated at different times owing to the political views of their owners. It has been modernised and altered at intervals according to the taste and the standard of comfort of the period, but to this day it retains all the spacious dignity of an old English country house.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. That was the last time I saw Blankney — except once more, in a dream, a singular incident which I will relate. And since it concerned my cousin Hugo (age 42), whose marriage I had attended that summer afternoon some two years before, I must first explain that though we had always been friendly when we met, of recent years I had not seen much of him, for I was often abroad, while all his interests, hunting and racing, were of a different kind from mine and tended to keep him in the country .... It occurred in the early spring of 1937, when I was living in a villa near Vevey, on the Lake of Geneva. One night I was very restless, waking up at about two, and finding myself unable to get to sleep again for hours Eventually, about 6.30 in the morning, I fell into a long, troubling and involved dream, which yet did not the realm of nightmare. In it, I was in the Saloon at Blankney again, and Hugo (age 42), the owner of it, was talking to me very urgently. His words were simple enough, but laden with a weight of presage, and of sad and menacing feeling, and I knew that in his last sentence he was conveying to me something importance. He said, "There will be a party here at Blankney in ten days' time. All the relations are coming. They arrive by special train in the morning, and leave by special train in the afternoon." .... Then I woke up ; to find I was being called by my servant. He handed me The Times of the previous day — it always arrived in Vevey twenty-four hours after it had come out in London. I sat up, still unreasonably distressed, opened the paper — and the first heading that caught my eye as I did so was Serious Illness of Lord Londesborough .... It was impossible to misapprehend so clear a portent, although in my dream seen in reverse: but I still hoped that I might be wrong, because I knew that all the members of Hugo's (age 42) family had hitherto been buried at Londesborough, and this detail, so incorrect, seemed to falsify my reading of it. Howbeit, I was still so much oppressed by the feeling of the dream, that I told two friends, who were staying with me at the time, of it and of the sequel in the paper .... For a while it appeared that Hugo (age 42) was better, but a week later he died, and three days after that was buried at Blankney.

Between 1939 and 1945 Blankney Hall was used as a WAAF Mess, and a Control Centre for RAF Digby. The house was severely damaged by fire in 1945.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. Blankney stood, a dead weight in the snow, pressing it down with a solidity pronounced even for an English country-house. For us it loomed large at the end of each year, and the roads of every passing month led nearer to it, an immense stone building, of regular appearance, echoing in rhythm the empty syllables of its name. The colour of lead outside, its interior was always brilliantly lit, its hospitable fires blazing, flickering like lions within the cages of its huge grates, so that it seemed to exist solely as a cave of ice, a magnificent igloo in the surrounding white and mauve negation. What was the purpose of these spacious, comfortable tents of snow, that appeared all the more luxurious because of being picthed in so desolate and empty a whiteness, and that were full of a continual stir? .... Ease, not beauty, was their aim ; for beauty impeaches comfort, disturbing the repose of the body with questions of the spirit and, worse still, pitting the skeleton against its encasing flesh .... So there were few fine pictures in the large rooms, leading one into the other, only perhaps one, the Lawrence of Elizabeth Denison, Marchioness Conyngham, founder of the family. There were pleasant portraits, such as that by Sir Francis Grant of Lord Albert Conyngham, her son, surrounded by a few pieces from the celebrated and superb collection he had formed, now, except for jewels and plate, all dispersed. Here and there, ivory mirrors and other sumptuous objcects, given by King George IV to Lady Conyngham, and bearing on them the Royal Arms, survived; but for the most part the rooms contained little to look at. The Saloon, chief sitting-room, was long and rather high, full of chairs and sofas, piled with cushions (the aim of which was plain, to get you to sit down and prevent you from getting up and so to waste your time), with tables with many newspapers lying folded on them, and the weekly journals, and green-baize card-tables, set ready for you to play. The light-coloured, polished floor had white fur rugs, warm enough and yet suggesting the pelts of the arctic animals that must prowl outside: but to counterbalance such an impression, there were tall palm-trees, and banks of malmaisons and carnations and poinsettias, a favourite flower of the time, a starfish cut out of red flannel, and the standard lamps glowed softly under shades of flounced and pleated silk that mimicked the evening dresses of the period. There were writing-tables, too, and silver vases, square silver frames, with crowns in silver poised above them, containing the photographs of foreign potentates, posing in their full panoply of flesh as Death's Head Hussars, or with flowing white cloaks and firemen’s helmets, their wives, placid, with folded hands — silver inkstands and lapis paper-weights, and near the fire-place, two screens, cut out of flat wood, and jocularly painted a hundred or so years before, to represent peasants in costume! On one wall hung a large portrait by a fashionable artist, of my aunt balancing her second son in an easy position near or on her shoulder. There were many silver cigarette-boxes ash-trays and boxes of matches of every size from giant to dwarf. Certainly the rooms had a supreme air of modish luxury, and no quality so soon comes to belong to the past — for the skeleton outlives its flesh .... What more do I recall: the broad, white passages — out of which led the bedrooms — , so thickly carpeted, and the white arches, on one side of the corridors, looking down on hall and staircase ? What else ? The warmth, the fumy, feathery scent of logs and wood ash, and a lingering odour, perhaps of rosewater, or some perfume of that epoch, a fragrance, too, of Turkish cigarettes .... And for a moment, I see the women, their narrow waists and full skirts, and the hair piled up, with a sweep, on their heads, or surrounding it in a circle. Above all, I hear the sound of music.

Sometimes a string band would be playing in the Saloon — Pink or Blue Hussars insinuating whole Hungarian charms of waltzes, gay as goldfinches — but more often the tunes would be ground out by innumerable mechanical organs. There seemed to be one or two in every passage. You turned a handle, and these vast machines, tall as cupboards — objects which, since they have been superseded by gramophone and radio, would today constitute museum pieces — , were set in motion, displaying beneath their plate-glass fronts whole re- volving, clashing trophies of musical instruments, violins that shuddered beneath their own playing, frantic drums, tam- bourines that rattled themselves as at a seance, and trumpets that sounded their own call to battle. I scarcely recollect the tunes they played, overtures by Rossini and Verdi, and — of this I am sure — some of the music of Johann Strauss’s Fledermaus. The warm golden air of these rooms trembled perpetually to martial or amorous strains, yet they are not in memory more characteristic of the place than are the sounds of the family voices, variations, that is to say, of the same voice. For this house was the meeting-ground of all the generations surviving of my mother’s family, and these tones were the particular seal and link of it, containing, as they did, a special quality of their own, lazy and luxuriant, sun-ripened as fruit upon old walls. They seemed left over from other centuries, even those of the youngest, and former ways of speech still persisted among the older members of the family, tricks of phrase that might have seemed an affectation ; but then, my relatives on this side did not read much, and so these ways were traditional. All learning came to them by word of mouth. And, at the same time that I hear again these voices, and the music, I hear, too, something scarcely less typical, the quarrelsome, rasping voices of packs of pet dogs, demanding to be taken out into the cold air, their bodies surrounding the feet of the women of the house, as they walked, with a moving, yapping rug of fur, just as in frescoes clouds are posed for the feet of goddesses. And as, at last, these creatures emerge into the open air, they bark yet more loudly, jumping up, lifting their ill-proportioned trunks to the level of their mistresses’ knees.

In 1960 the remains of Blankney Hall were demolished.

Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Lincolnshire, Blankney, St Oswald's Church

Before 1100 the original St Oswald's Church, Blankney was constructed; it was restored around 1820, and again between 1879 and 1881 by Carpenter and Ingelow. There is little of the original church remaining.

Around 1400. Floor monument to unknown person at St Oswald's Church, Blankney.

In Jun 1789 Reverend Henry Chaplin was born to Charles Chaplin (age 30) and Elizabeth Taylor. He was baptised on 08 Jun 1789 at St Oswald's Church, Blankney.

Between 1805 and 1807 the West Tower of St Oswald's Church, Blankney was constructed. The interior arch has evidence of an earlier arch.

In 1851 Reverend Philip Henry Surtees Raine was appointed Rector of St Oswald's Church, Blankney

In 1853 Reverend Brook George Bridges 6th Baronet (age 50) was appointed Rector of St Oswald's Church, Blankney.

After 22 Nov 1858. Monument to Caroline Fane (deceased), wife of Charles Chaplin (age 72) commissioned by her two nieces Louisa Anne Fleming Fane (age 44) and Julia Charlotte Fane (age 33) at St Oswald's Church, Blankney.

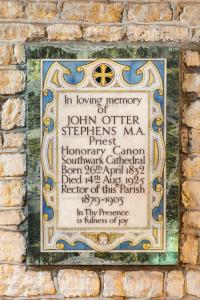

In 1879 Reverend John Otter Stephens (age 46) was appointed Rector of St Oswald's Church, Blankney which office he held until 1903.

On 08 Oct 1881 Florence Chaplin was born to Henry Chaplin 1st Viscount Chaplin (age 40) and Florence Sutherland Leveson-Gower (age 26). Florence Sutherland Leveson-Gower (age 26) died from childbirth two days later. She was buried in the churchyard of St Oswald's Church, Blankney. Her husband's account of her last days .... Lady Florence's second daughter was born on Saturday, and her birth was followed by convulsions from which she never recovered consciousness. Through the night Dr. Brook and her husband watched by her, and on Sunday there was a slight improvement which continued throughout the day. "At that time ", says Mr. Chaplin (age 40)," my spirit had revived, and I allowed myself, foolishly perhaps, to become quite sanguine—only, alas, to be bitterly disappointed." On Sunday evening the breathing again became more rapid, and on Monday afternoon "my darling passed away, with her head resting on my (age 40) shoulder, and with the most beautiful expression on her face as she died".

After 08 Oct 1881. Monument to Florence Sutherland Leveson-Gower (deceased) commissioned by her husband Henry Chaplin 1st Viscount Chaplin (age 40), sculpted by Joseph Edgar Boehm (age 47). His memoir by his his daughter Edith ... "After her funeral at Blankney Mr. Chaplin returned a stricken man to Dunrobin. To the end of his life the memory of this radiant being, who for five years had given him perfect happiness, held the most sacred place in his memory—a place which was never to be usurped by another woman. He found some consolation in commissioning the beautiful kneeling marble figure of Lady Florence (deceased) by Sir Edgar Boehm (age 47), which he placed in the church of St. Oswald at Blankney — the church in which she had taken so deep an interest.

1883. Lych Gate at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. By George Frederick Bodley (age 55). Inscription over the gate: 'ERECTED IN MEMORY OF FLORENCE CHAPLIN, 1883'.

Around 1900. Reredos at St Oswald's Church, Blankney.

On 29 May 1923 Henry Chaplin 1st Viscount Chaplin (age 82) died. He was buried at St Oswald's Church, Blankney next to his wife. His son Eric Chaplin 2nd Viscount Chaplin (age 45) succeeded 2nd Viscount Chaplin of Saint Oswald's in Blankney in Lincolnshire. Gwladys Alice Wilson Viscountess Chaplin (age 42) by marriage Viscountess Chaplin of Saint Oswald's in Blankney in Lincolnshire.

Eric Chaplin 2nd Viscount Chaplin: On 27 Sep 1877 he was born to Henry Chaplin 1st Viscount Chaplin and Florence Sutherland Leveson-Gower. On 03 Aug 1905 Eric Chaplin 2nd Viscount Chaplin and Gwladys Alice Wilson Viscountess Chaplin were married at Warter Hall aka Priory. On 12 Sep 1949 Eric Chaplin 2nd Viscount Chaplin died. His son Anthony Chaplin 3rd Viscount Chaplin succeeded 3rd Viscount Chaplin of Saint Oswald's in Blankney in Lincolnshire. Alvilde Bridges Viscountess Chaplin by marriage Viscountess Chaplin of Saint Oswald's in Blankney in Lincolnshire.

Gwladys Alice Wilson Viscountess Chaplin: In 1881 she was born to Charles Henry Wilson 1st Baron Nunburnholme and Florence Jane Helen Wellesley Baroness Nunburnholme. In 1971 Gwladys Alice Wilson Viscountess Chaplin died.

After 14 Aug 1925. Monument to Reverend John Otter Stephens (deceased) at St Oswald's Church, Blankney.

Reverend John Otter Stephens:

On 26 Apr 1832 he was born.

In 1879 he was appointed Rector of St Oswald's Church, Blankney which office he held until 1903.

On 16 Jun 1887 he and Emma Charlotte Leslie-Melville were married. On 14 Aug 1925 he died.

On 14 Aug 1925 he died.

On 07 Sep 1935 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough (age 40) and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough (age 32) were married at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. He the son of William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

On 17 Apr 1937 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough (age 42) died. He was buried at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. The Earl had become ill and it was decided to to move him to London for treatment; he died on the journey. Earl Londesborough in Yorkshire extinct. The impact of death duties necessitated the sale of Blankney, Lincolnshire to Mr William Parker of Norfolk. The Countess, Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough (age 33), and her daughter Zinnia Rosemary Denison, continued to live on the estate.

Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough:

On 13 Nov 1894 he was born to William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

On 12 Sep 1920 George Denison 3rd Earl of Londesborough died unmarried. His brother Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough succeeded 4th Earl Londesborough in Yorkshire. On 07 Sep 1935 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough were married at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. He the son of William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. That was the last time I saw Blankney — except once more, in a dream, a singular incident which I will relate. And since it concerned my cousin Hugo, whose marriage I had attended that summer afternoon some two years before, I must first explain that though we had always been friendly when we met, of recent years I had not seen much of him, for I was often abroad, while all his interests, hunting and racing, were of a different kind from mine and tended to keep him in the country .... It occurred in the early spring of 1937, when I was living in a villa near Vevey, on the Lake of Geneva. One night I was very restless, waking up at about two, and finding myself unable to get to sleep again for hours Eventually, about 6.30 in the morning, I fell into a long, troubling and involved dream, which yet did not the realm of nightmare. In it, I was in the Saloon at Blankney again, and Hugo, the owner of it, was talking to me very urgently. His words were simple enough, but laden with a weight of presage, and of sad and menacing feeling, and I knew that in his last sentence he was conveying to me something importance. He said, "There will be a party here at Blankney in ten days' time. All the relations are coming. They arrive by special train in the morning, and leave by special train in the afternoon." .... Then I woke up ; to find I was being called by my servant. He handed me The Times of the previous day — it always arrived in Vevey twenty-four hours after it had come out in London. I sat up, still unreasonably distressed, opened the paper — and the first heading that caught my eye as I did so was Serious Illness of Lord Londesborough .... It was impossible to misapprehend so clear a portent, although in my dream seen in reverse: but I still hoped that I might be wrong, because I knew that all the members of Hugo's family had hitherto been buried at Londesborough, and this detail, so incorrect, seemed to falsify my reading of it. Howbeit, I was still so much oppressed by the feeling of the dream, that I told two friends, who were staying with me at the time, of it and of the sequel in the paper .... For a while it appeared that Hugo was better, but a week later he died, and three days after that was buried at Blankney.

On 07 Sep 1935 Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough were married at St Oswald's Church, Blankney. He the son of William Henry Francis Denison 2nd Earl Londesborough and Grace Adelaide Fane Countess Londesborough.

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2. That was the last time I saw Blankney — except once more, in a dream, a singular incident which I will relate. And since it concerned my cousin Hugo, whose marriage I had attended that summer afternoon some two years before, I must first explain that though we had always been friendly when we met, of recent years I had not seen much of him, for I was often abroad, while all his interests, hunting and racing, were of a different kind from mine and tended to keep him in the country .... It occurred in the early spring of 1937, when I was living in a villa near Vevey, on the Lake of Geneva. One night I was very restless, waking up at about two, and finding myself unable to get to sleep again for hours Eventually, about 6.30 in the morning, I fell into a long, troubling and involved dream, which yet did not the realm of nightmare. In it, I was in the Saloon at Blankney again, and Hugo, the owner of it, was talking to me very urgently. His words were simple enough, but laden with a weight of presage, and of sad and menacing feeling, and I knew that in his last sentence he was conveying to me something importance. He said, "There will be a party here at Blankney in ten days' time. All the relations are coming. They arrive by special train in the morning, and leave by special train in the afternoon." .... Then I woke up ; to find I was being called by my servant. He handed me The Times of the previous day — it always arrived in Vevey twenty-four hours after it had come out in London. I sat up, still unreasonably distressed, opened the paper — and the first heading that caught my eye as I did so was Serious Illness of Lord Londesborough .... It was impossible to misapprehend so clear a portent, although in my dream seen in reverse: but I still hoped that I might be wrong, because I knew that all the members of Hugo's family had hitherto been buried at Londesborough, and this detail, so incorrect, seemed to falsify my reading of it. Howbeit, I was still so much oppressed by the feeling of the dream, that I told two friends, who were staying with me at the time, of it and of the sequel in the paper .... For a while it appeared that Hugo was better, but a week later he died, and three days after that was buried at Blankney.

Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough: On 15 May 1903 she was born to Edgar Lubbock.

Zinnia Rosemary Denison: On 25 Nov 1937 she was born to Hugo Denison 4th Earl of Londesborough and Marigold Lubbock Countess Londesborough. She was born posthumously her father having died six months before her birth. On 13 Jul 1997 Zinnia Rosemary Denison died.